Archive:Foreign direct investment statistics

- Data from June 2013. Most recent data: Further Eurostat information, Main tables and Database. Planned article update: July 2014.

(EUR billion) - Source: Eurostat (bop_fdi_main)

(% of extra EU-27 outward flows) - Source: Eurostat (bop_fdi_main)

(EUR billion) - Source: Eurostat (bop_fdi_main)

(EUR 1 000 million) - Source: Eurostat (bop_fdi_pos_r2)

This article gives an overview of foreign direct investment (FDI) statistics for the European Union (EU) in relation to year-end stocks, annual flows and income. The analysis mainly covers the period 2009 to 2011, but provisional data on FDI flows for 2012 are also included; note that the latter are based on provisional quarterly figures that have been annualised for the purpose of this analysis.

Main statistical findings

Key points

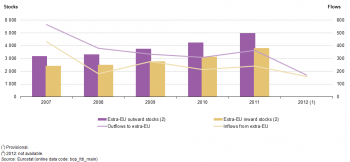

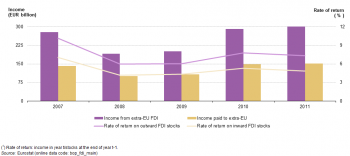

EU-27 foreign direct investment (FDI) is still affected by the global financial and economic turmoil. In 2012, EU-27 outward flows declined sharply, down 53 % compared with 2011, and recorded their lowest level since 2004. Similarly, EU-27 inward flows decreased from the previous year — down 34 %, to their lowest level since 2005. EU-27 FDI flows in 2012 therefore stood at more than 60 % below their record peaks of 2007 in terms of both inward and outward investment relations with the rest of the world (see Figure 1). The income rate of return from both EU-27 outward and inward investment in 2011 was slightly down from the previous year but remained above the rates of 2008 and 2009 (see Figure 3). As in earlier years, FDI flows channelled through special-purpose entities (SPE)[1] played a very significant role in the results for 2012.

FDI flows

FDI flows increased in 2011 but declined again in 2012

Between 2009 and 2012 EU-27 FDI flows remained affected by the global financial and economic crisis. Total FDI outflows decreased by 8 % in 2010, mainly due to a sharp decline in equity capital, though partially compensated by an increase in reinvested earnings. EU-27 inward flows declined in 2010 by 22 %. In 2011, outward flows of FDI recovered slightly, up 18 %, again due to a recovery in equity capital invested outside the EU-27, while inward flows also recovered partially, up 13 %; other capital contributed the most to the positive change, together with reinvested earnings.

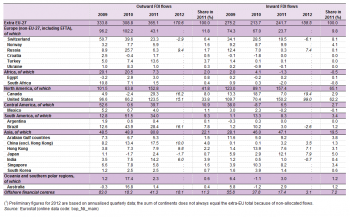

EU-27 direct investment abroad in 2011 grew mainly due to increased FDI activity with some traditional partners — the United States (up 87 % to EUR 123.5 billion) and Canada (moving from disinvestment in 2010 to investment of EUR 29.3 billion in 2011). The central American countries (EUR 39.7 billion) also contributed to the positive change, mainly due to increased EU-27 FDI activities with offshore financial centres (OFC) located in this area, where special-purpose entities play an important role. In 2011, EU-27 FDI in Asia increased from EUR 48.9 billion to EUR 80.8 billion, and this increase was not restricted to its main partner countries.

The United States also remained the most important player in relation to EU-27 inward direct investment flows in 2011. Flows from the United States (EUR 150.2 billion) into the EU-27 more than doubled from the previous year and thereby accounted for almost two thirds of total EU-27 inward FDI in 2011. In fact, this compensated for reduced FDI from other traditional partners like Switzerland, Canada and offshore financial centres, as well as Brazil. Overall, Asian investors retained their FDI in the EU-27 at the level of the previous year, although FDI from South Korea, Hong Kong and Singapore fell, while that from China, Japan, the Arabian Gulf countries, as well as India all increased.

The EU-27’s overall FDI activity with economies in south-east Asia was less affected by the crisis during the period 2009–11. The EU-27’s FDI activity with Australia was relatively volatile throughout the period studied. In 2011, this partner attracted only 0.4 % (EUR 1.4 billion) of the EU-27’s outward FDI but accounted for 1.2 % (EUR 2.9 billion) of the EU-27’s inward flows. Provisional figures for 2012 show a big downturn in EU-27 FDI flows in both directions. EU-27 outward flows declined by 53 % compared with 2011 and recorded their lowest level since 2004; many of the EU’s principal investment partners were affected by these developments.

In 2012, EU-27 direct investment into the United States shrank to less than one eighth of its 2011 level (a fall of 88 %), while the EU-27’s outward FDI in Switzerland and Japan was less than the level of (earlier) outward FDI withdrawn from these countries such that overall the EU-27’s outward FDI flows to these countries was negative (a disinvestment). EU-27 FDI flows into Canada, Brazil, India and offshore financial centres in 2012 were approximately half their 2011 level. Nevertheless, an increase in EU-27 direct investment activity was registered in Russia (up from EUR 6.3 billion in 2010 to EUR 9.4 billion in 2011) and Hong Kong (from EUR 7.9 billion to EUR 9.8 billion).

Similarly, EU-27 inward flows of FDI decreased in 2012 compared with the previous year — down 34 % to their lowest level since 2005. In line with this overall trend, the United States’ direct investment into the EU-27 was down 34 % in 2012, although the United States remained the main source of incoming FDI. Inward flows of FDI from offshore financial centres also declined sharply in 2012 (down to EUR 3.1 billion from EUR 17.4 billion in 2011), while Switzerland, Brazil and India recorded disinvestment in the EU-27 in 2012, as the extent of (previous) inward FDI that was withdrawn exceeded new inward FDI. Having fallen sharply in 2011, inward FDI from Russia and Canada rebounded in 2012 to exceed 2010 levels.

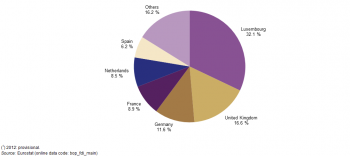

EU-27’s main sources of outgoing FDI

FDI flows can vary considerably from one year to another, influenced mainly by large mergers and acquisitions. In the period 2010–12, Luxembourg had the largest share (32 %) of EU-27 FDI outward flows because special-purpose entities handle most of Luxembourg’s total direct investment. Special-purpose entities also play an important role in other EU-27 Member States, especially the Netherlands, Austria, Hungary and Cyprus, but the data presented here exclude special-purpose entities for these countries.

Luxembourg’s outgoing FDI more than halved in 2012 compared with 2011, though Luxembourg remained the leading EU-27 investor in non-member countries. Offshore financial centres were the top destination for FDI from Luxembourg, showing the importance of the financial sector for this country. Unlike previous years, the United States and Switzerland were not among the three top recipients of FDI from Luxembourg in 2012.

In 2012, the United Kingdom recorded a sharp drop in outward FDI flows to its traditional partner, the United States, though its direct investment flows increased to Canada, Switzerland and offshore financial centres.

FDI stocks

Faster growth in 2011

EU-27 outward and inward FDI stocks (or positions) grew steadily in 2011: outward stocks by 17 % and inward stocks by 21 %; this can be compared with 13 % growth for each direction in 2010.

North America remains the main location of EU-27 FDI outward stocks in non-member countries

At the end of 2011, North America had the biggest share (33 %) of EU-27 FDI stocks abroad (see Map 1). The United States alone accounted for some 29 % (EUR 1 421 billion) of total EU-27 outward stocks, with growth of 11 % in 2011 compared with 6 % growth in 2010. The main EU-27 holders of FDI stocks in the United States were the United Kingdom (18 %), France and Germany (both 13 %).

Switzerland was the second most important location for EU-27 outward FDI positions at the end of 2011, accounting for 12 % of total stocks, the main activity being financial intermediation. At the end of 2011, Brazil was the third main location with a 5 % share of EU-27 FDI outward stocks, having overtaken Canada by the end of 2010, which underlined the increased interest of EU-27 investors in this country.

In Asia, the main location for EU-27 outward FDI stocks were Hong Kong, Singapore and China, together accounting for half of the EU-27’s FDI positions in Asia (excluding the Arabian Gulf countries) at the end of 2011. Japan (EUR 85.8 billion) lost its position among the three top Asian partners for EU-27 FDI outward positions, but still remained ahead of India, South Korea and Indonesia. In Africa, the main destinations for EU-27 FDI stocks were South Africa (EUR 79.5 billion), Nigeria (EUR 32.4 billion) and Egypt (EUR 25.8 billion). Growth for the EU-27’s FDI outward stocks in South Africa slowed to 5 % in 2011, and South Africa moved out of the EU-27’s top 10 FDI partners as it and Japan were overtaken by China (see Table 2).

The United States was the main holder of inward FDI stocks in the EU-27

At the end of 2011, the United States held just over one third (35 %; EUR 1 344 billion) of total EU-27 FDI inward stocks from the rest of the world (see Table 2). The United States thus consolidated its position as the major FDI stocks holder in the EU-27, having invested, as of the end of 2010, mostly in the financial services sector, followed by manufacturing; one third of the latter was in computer, electronic and optical products manufacturing.

Similar to the ranking for FDI outward positions, Switzerland was the second biggest FDI stock holder in the EU-27 in 2011, with stocks valued at EUR 467.3 billion, 18 % more than at the end of 2010.

Other countries with significant shares in EU-27 FDI inward positions at the end of 2011 were Japan and Canada (4 % each), followed by Brazil, Singapore, Hong Kong and Russia. In 2011, the highest annual growth among these partners was achieved by Hong Kong (54 %), followed at some distance by Singapore (12 %). China's FDI stocks in the EU-27 more than doubled in 2011, but by the end of 2011 China was still not among the top 10 investors (in terms of inward FDI positions) in the EU-27.

Continued dominance of financial services

At the end of 2010 the EU-27 had a positive FDI balance — in other words, outward stocks of FDI exceeded inward stocks (see Table 3). The activity structure of EU-27 FDI stocks remained relatively steady in 2010, with a negative balance in two of the smaller services sectors (real estate activities and other services) as well as the miscellaneous category of other (which also includes unallocated positions).

Services made by far the largest contribution to both outward (59 %) and inward (57 %) FDI stocks for the EU-27, and their respective shares of total stocks at the end of 2010 were slightly greater than at the end of 2009. Almost three fifths of services stocks (both inward and outward) were held in financial and insurance activities, which themselves grew moderately during 2010. Almost all services subsectors contributed to the positive development, the highest growth being recorded for information and communication services. On the other hand, EU-27 inward stocks decreased in trade (including repairs of motor vehicles) as well as transportation and storage, while both inward and outward stocks decreased for accommodation and food service activities.

Thanks to steady increases in its main subsectors, EU-27 stocks in manufacturing grew in 2010: a 20 % increase for outward stocks and a 31 % increase for inward stocks. The contributions of the construction and mining and quarrying sectors to total EU-27 stocks at the end of 2010 remained relatively unchanged from the previous year.

Income from FDI

EU-27 net income decreased moderately in 2011

The EU-27’s investment income from and to non-member countries increased in 2011 to reach record values of EUR 312.1 billion of income received (from outward FDI) and EUR 151.7 billion of income paid (from inward FDI). The EU-27’s resulting net income from the rest of the world reached EUR 160.4 billion in 2011, a new peak and 12 % higher than in 2010. The EU-27’s investment income (from FDI) balance in 2011 was 1.27 % of GDP, compared with 1.17 % in 2010.

Following a partial recovery in 2010, a slowdown in FDI income growth in 2011 brought rates of return[2] down to 7.3 % for EU-27 FDI outward stocks (in other words, inflows of income) and 4.8 % for EU-27 FDI inward stocks (in other words, outflows of income) — see Figure 3.

Data sources and availability

FDI statistics in the EU are collected in accordance with Regulation (EC) No 184/2005 of the European Parliament and of the Council on Community statistics concerning balance of payments, international trade in services and foreign direct investment.

The methodological framework used is that of the OECD benchmark definition of foreign direct investment — third edition, which provides a detailed operational definition that is fully consistent with the IMF’s balance of payments manual (fifth edition).

This article is based on FDI data that were available in Eurostat’s database at the beginning of June 2013. The series in the database covered the period from 1992 to 2011, analysed by partner, activity and type of direct investment (equity capital, loans and reinvested earnings). The aggregated FDI figures that are presented in this article for 2012 are provisional data based on annualised quarterly balance of payments data.

EU-27 aggregates include special-purpose entities, which are a particular class of enterprises (often empty shells or holding companies) not included in all countries’ national statistics. Consequently, EU-27 aggregates are not simply the sum of national figures.

Context

In a world of increasing globalisation, where political, economic and technological barriers are rapidly disappearing, the ability of a country to participate in global activity is an important indicator of its performance and competitiveness. In order to remain competitive, modern-day business relationships extend well beyond the traditional international exchange of goods and services, as witnessed by the increasing reliance of enterprises on mergers, partnerships, joint ventures, licensing agreements, and other forms of business cooperation.

FDI may be seen as an alternative economic strategy, adopted by those enterprises that invest to establish a new plant/office, or alternatively, purchase existing assets of a foreign enterprise. These enterprises seek to complement or substitute international trade, by producing (and often selling) goods and services in countries other than where the enterprise was first established.

There are two kinds of FDI: the creation of productive assets by foreigners, or the purchase of existing assets by foreigners (for example, through acquisitions, mergers, takeovers). FDI differs from portfolio investments because it is made with the purpose of having control, or an effective voice, in the management of the enterprise concerned and a lasting interest in the enterprise. Direct investment not only includes the initial acquisition of equity capital, but also subsequent capital transactions between the foreign investor and domestic and affiliated enterprises.

Conventional international trade is less important for services than for goods. While trade in services has been growing, the share of services in total intra-EU trade has changed little during the last decade. However, FDI is expanding more rapidly for services than for goods, and is increasing at a more rapid pace than international trade in services. As a result, the share of services in total FDI flows and positions has increased substantially, as the service sector has become increasingly international.

See also

- Africa-EU - key statistical indicators

- Balance of payment statistics

- Foreign affiliates statistics - FATS

- Global value chains - international sourcing to China and India

- Latin America-EU - economic indicators, trade and investment

Further Eurostat information

Main tables

- European Union direct investments (t_bop_fdi)

Database

- European Union direct investments (bop_fdi)

Dedicated section

Methodology / Metadata

- European Union direct investments (ESMS metadata file - bop_fdi_esms)

Source data for tables, figures and maps (MS Excel)

Other information

External links

- OECD Benchmark Definition of Foreign Direct Investment

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) - FDI Statistics

Notes

- ↑ Special-purpose entities are mainly financial holding companies, foreign-owned, and principally engaged in cross-border financial transactions, with little or no activity in the Member State of residence.

- ↑ The FDI rate of return is measured here as (FDI income of year t) / (stock of FDI at the end of year t-1).