Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels

Data extracted in April 2025.

Planned article update: June 2026.

Highlights

This article is a part of a set of statistical articles, which are based on the Eurostat publication ’Sustainable development in the European Union — Monitoring report on progress towards the SDGs in an EU context — 2025 edition’. This report is the ninth edition of Eurostat’s series of monitoring reports on sustainable development, which provide a quantitative assessment of progress of the EU towards the SDGs in an EU context.

SDG 16 calls for peaceful and inclusive societies based on respect for human rights, protection of the most vulnerable, the rule of law and good governance at all levels. It also envisions transparent, effective and accountable institutions.

Peace, justice and strong institutions in the EU: overview and key trends

Peace and security are prerequisites for sustainable development, in line with the integrated nature of the 2030 Agenda. Peace, security, democracy, the rule of law and respect for fundamental rights are also founding values of the EU. Monitoring SDG 16 in an EU context focuses on personal security, access to justice and trust in institutions within the EU. The EU’s progress over the most recent five-year period of available data has been mixed in all these areas and has slowed compared with previous years. While deaths due to homicide or assault and the perceived occurrence of crime, violence and vandalism have fallen, the number of victims of trafficking in human beings in the EU has increased. Government expenditure on law courts has grown significantly and more than half of Europeans consider their justice system to be independent, although this share has declined over the past five years. The perceived level of corruption in the EU worsened slightly in 2024.

Peace and personal security

Safety is a crucial aspect of a person’s life. Insecurity is a common source of fear and worry, and negatively affects quality of life. Physical insecurity includes all the external factors that could potentially put an individual’s physical integrity in danger. Crime is one of the most obvious causes of insecurity. Analyses of physical insecurity usually combine two aspects: the subjective perception of insecurity and the objective lack of safety. In this chapter, subjective perception of insecurity is monitored by perception of crime, while objective security is measured by two indicators: homicide death rate and victims of human trafficking.

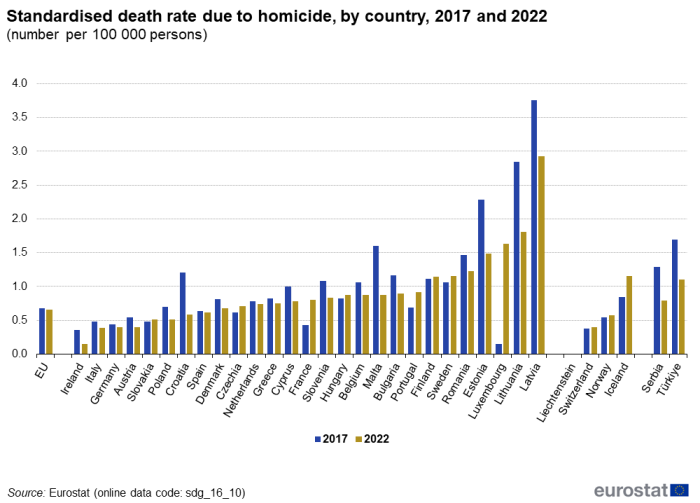

The EU has become a safer place to live

In the EU, deaths due to homicide fell steadily between 2007 and 2022, reaching a rate of 0.7 deaths per 100 000 people. This corresponds to a reduction of 40% over the assessed 15-year period. In the short-term period between 2017 and 2022, the rate of decline was more moderate, at 3%, indicating stagnation at a low level. The long-term decrease in homicides in the EU has gone hand in hand with improvements in people’s perception of crime, violence or vandalism. Since 2010, the share of people reporting the occurrence of such problems in their area has fallen in the EU. In 2023, 10.0% of the population felt affected by these issues, which is 3.1 percentage points less than in 2010 and the lowest value recorded.

The perception of being affected by crime, violence or vandalism differs across socio-demographic sub-groups of the EU population and by degrees of urbanisation. In 2023, 12.3% of the population living in households with an equivalised disposable income below the poverty threshold — set at 60% of the national median equivalised income — felt affected by such problems. However, this was the case for only 9.6% of the population living in households above the poverty threshold in that year. Similarly, in 2023 the perceived occurrence of crime, violence or vandalism in cities (15.4%) was more than three times higher than in rural areas (4.7%) and almost twice as high as in towns and suburbs (7.8%) [1].

Perceived exposure to crime does not always match observed crime rates

National figures show that the perceived exposure to crime, violence or vandalism in 2023 was 15 times higher in the most affected country (20.9% of the population in Greece) than in the least affected country (1.4% in Croatia). However, country differences in this subjective indicator need to be treated with caution. Research suggests that crime rates from police registers and the subjective exposure to crime may differ, as population groups with low victimisation rates may be particularly afraid of crime (the so-called ‘fear of victimisation paradox’) [2].

Men and women face different risks of experiencing crime, depending on the type of crime

Deaths due to homicide in the EU show a significant gender gap. While death rates due to homicide have fallen for both sexes, they remain about twice as high for men (0.9 deaths per 100 000 persons in 2022, compared with 0.4 deaths per 100 000 persons for women) [3]. A study by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and UN Women shows that the gap is even bigger worldwide since 80% of all homicides were committed against men and boys in 2022 [4].

However, while men have a higher overall risk of being killed, women have a significantly higher risk of being killed by their intimate partners or family members. Globally, intimate partner- or family-related homicides accounted for 55% of women who were killed in 2022, while this was only the case for 12% of male homicides [5]. At the EU level, women are about twice as likely as men to be victims of intentional homicide by family and relatives or their intimate partner. In 2022, 0.4 out of 100 000 women were victims of such homicide, compared with only 0.2 per 100 000 men [6]. This is an issue of concern when considering the broader concept of violence against women, encompassing all forms of physical, sexual and psychological violence.

Data from Eurostat’s official crime statistics on intentional homicide and sexual offences show that women are much more likely to be victims of sexual offences than men. In 2022, 64 out of 100 000 women were victims of sexual assault, and 38 out of 100 000 women were victims of rape. The rates were significantly lower for men, with 11 per 100 000 men for sexual assault and 4 out of 100 000 men for rape [7].

The prevalence of homicide and other types of violence varies greatly across the EU. However, cross-country comparisons of the crime statistics should be made with caution. Comparability is affected by different legal definitions concerning offenders and victims, different levels of police efficiency and the stigma associated with disclosing cases of violence against women [8] (see the article on SDG 5 ‘Gender equality' for more information on gender-based violence).

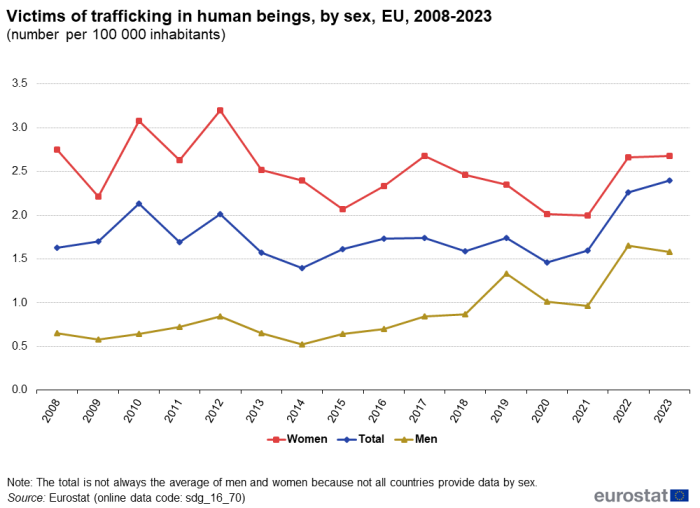

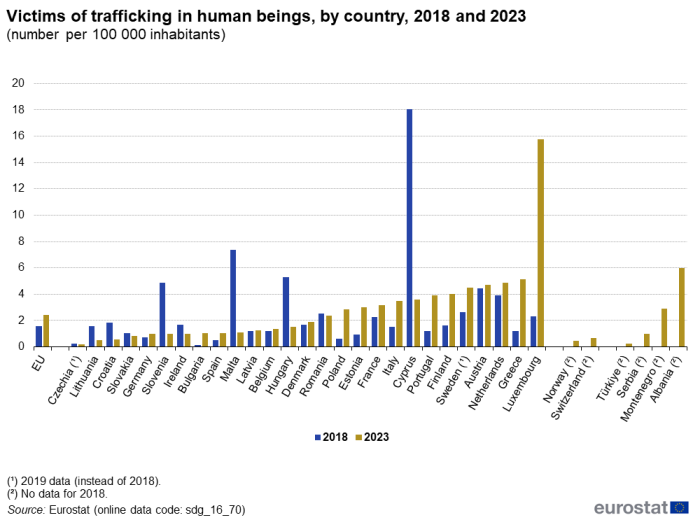

The number of detected victims of trafficking in human beings has increased over the past five years

Human trafficking is a global crime that degrades people to commodities and exploits them for profit. It destroys individuals’ lives by depriving people of their dignity, freedom and fundamental rights. Sexual and labour exploitation are the most common purposes of trafficking but forced begging, forced criminality and organ trafficking are also prevalent forms of exploitation [9]. In the EU, the number of victims of human trafficking increased by 51% over the past five years, reaching 2.4 per 100 000 inhabitants in 2023 — the highest value on record. This corresponds to 10 793 registered victims in that year. The actual number is likely to be significantly higher because many victims remain undetected [10]. The strongest increase in the number of victims of human trafficking happened in 2022, by 41%, and can be attributed to armed conflicts, natural and man-made disasters, and displacement, which increase the number of victims of trafficking exploited within and outside crisis areas [11]. Several Member States signalled that Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine contributed to higher awareness of this crime, prompting the introduction of preventive measures which have led to a recent increase in the detection of victims [12].

Women in the EU are more likely to be victims of human trafficking than men, with a rate of 2.7 per 100 000 inhabitants, as opposed to 1.6 per 100 000 inhabitants for men in 2023. This gap has significantly narrowed over the years, as the rate for women has declined by 2.5% since 2008, while for men it increased by 143.1%. This is also in line with global figures that show that the share of women and girls in detected victims of human trafficking in the world decreased from 84% in 2004 to 60% in 2020 [13]. In the EU, 63.3% of registered victims of trafficking in human beings were women or girls in 2023 [14].

In 2023, sexual exploitation remained the most common form of exploitation in the EU Member States, representing 43.8% of all recorded cases of trafficking, although this share has fallen since 2008. Meanwhile, the share of labour exploitation has been increasing over the years, reaching 36.0% of cases in 2023. Other forms of exploitation, including organ removal, benefit fraud, criminal activities and forced begging, accounted for 20.2% of cases in the same year [15].

Access to justice

Well-functioning justice systems are an important structural condition on which EU Member States base their sustainable growth and social stability policies. Whatever the model of the national justice system or the legal tradition in which it is anchored, quality, independence and efficiency are among the essential parameters of an ‘effective justice system’. As there is no single agreed way of measuring the quality of justice systems, the budget actually spent on courts is used here as a proxy for this topic. Moreover, judges need to be able to make decisions without interference or pressure from governments, politicians or economic actors, to ensure that individuals and businesses can fully enjoy their rights. The perceived independence of the justice system is used to monitor this aspect.

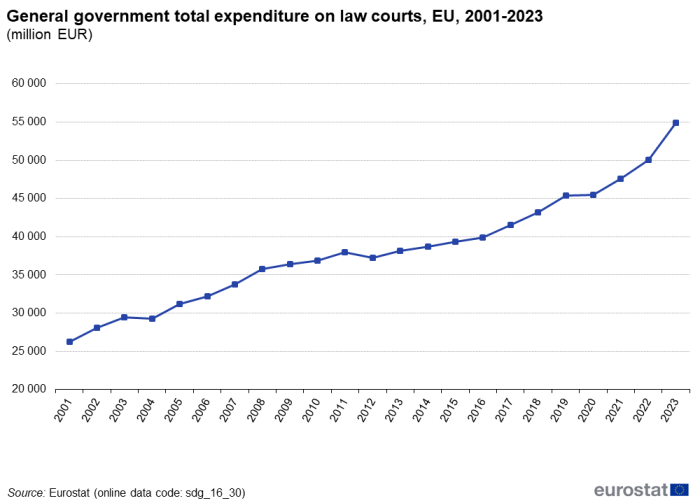

EU expenditure on law courts has grown over the past few years

In the EU, general government expenditure on law courts has risen by 54% since 2008, reaching EUR 54.9 billion in 2023. In per capita terms, this corresponds to a 49% increase from EUR 81.5 per inhabitant in 2008 to EUR 121.7 per inhabitant in 2023. However, when viewed as a share of total government expenditure, spending on law courts remained stable at 0.7% between 2007 and 2019. In 2020, the share decreased to 0.6% of total expenditure, largely due to increases in other government expenditure to mitigate the economic and social impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and remained at this level through 2021 and 2022. In 2023, it increased to 0.7% again. In relation to GDP, expenditure on law courts has also been stable since 2008, at 0.3% of GDP [16].

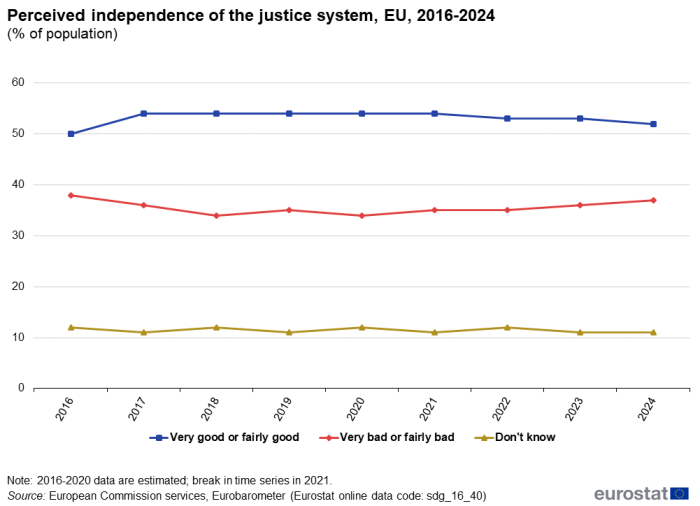

Perceived independence of the justice system has slightly declined since 2019

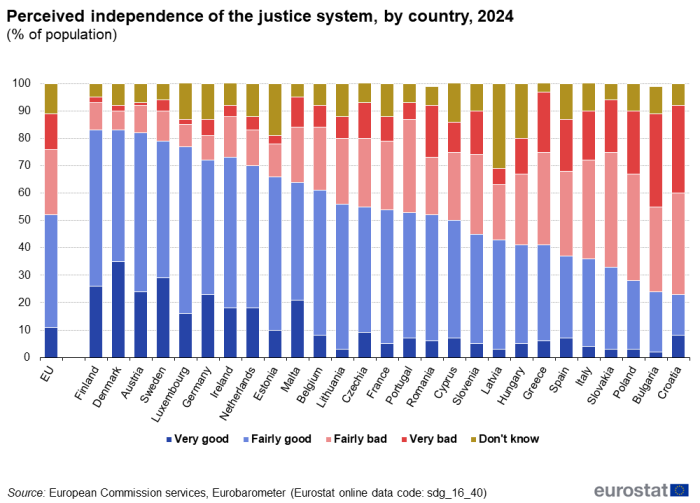

In 2024, 52% of EU inhabitants rated the independence of the courts and judges in their country as ‘very good’ or ‘fairly good’, two percentage points lower than in 2019. At the same time, the perception of ‘very bad’ or ‘fairly bad’ increased by two percentage points, from 35% to 37%. Interference or pressure from government and politicians was the reason most frequently given for a bad rating of perceived independence of courts and judges [17]. The opinion about the independence of courts and judges varied significantly across Member States. While in Denmark, Finland and Austria, most respondents (83%, 83% and 82%, respectively) rated the independence of their courts and judges as ‘very good’ or ‘fairly good’, this was only the case for 23% of respondents in Croatia and 24% in Bulgaria [18].

Age, employment status, education and experience with the justice system seem to have a notable effect on the perception of the independence of the justice system. In 2024, 56% of 15- to 24-year-old respondents in the EU gave a good rating, compared with 51% of respondents aged 55 or over. Employees (58%) were more likely to give a good rating than people who were not employed (50%), self-employed people (47%) or manual workers (44%). The longer people remained in education, the more likely they were to rate the independence of courts and judges as good: 55% of those who completed education aged 20 or above gave a good rating, compared with 46% of those who completed education aged 15 or younger. Notably, respondents who had been involved in a dispute that had gone to court were more evenly split between those who rated their system as good (44%) and bad (49%) than those who had not been to court (53% good, 36% bad) [19].

Trust in institutions

Effective justice systems are a prerequisite for the fight against corruption. Corruption causes social harm, especially when it is orchestrated by organised crime groups to commit other serious crimes, such as trafficking in drugs and humans. Corruption can undermine trust in democratic institutions and weaken the accountability of political leadership. It also inflicts financial damage by lowering investment levels, hampering the fair operation of the internal market and reducing public finances.

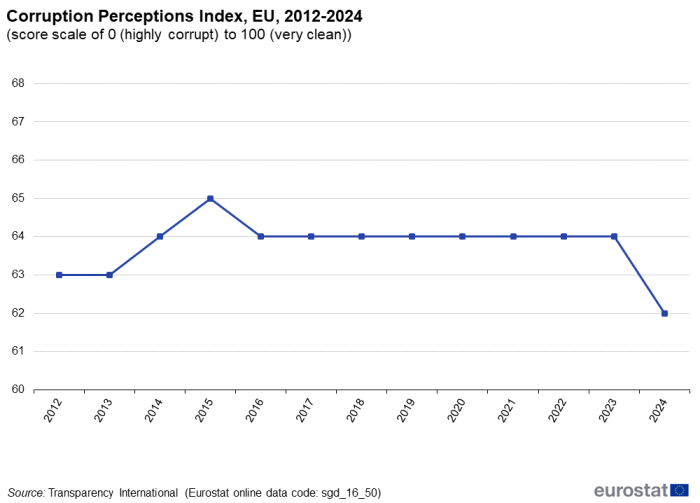

Perceptions of corruption increased across the EU in 2024

Because there is no meaningful way to assess absolute levels of corruption in countries or territories based on hard empirical evidence, capturing the perception of corruption of those in a position to make an assessment of public-sector corruption is currently the most reliable method of comparing relative corruption levels across countries. According to Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), the EU countries scored on average 62 on a scale from 0 (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean) in 2024. The corruption perception in the EU stagnated between 2016 and 2023, but decreased by two points in 2024, reaching the lowest value on record. This is the result of 17 EU Member States showing a decline in their corruption perception score in 2024 compared to the previous year.

Despite the decline in 2024, the EU’s score was still 19 points above the world average score of 43. On a country level, EU countries continued to rank among the least-corrupt globally in 2024 and made up more than a half of the global top 10 least-corrupt countries. Within the EU, northern European countries achieved the best scores, with Denmark, Finland and Luxembourg leading the ranking. At the other end of the scale, Hungary, Bulgaria and Romania showed the highest levels of perceived corruption across the EU, ranking at positions 82, 76 and 65, respectively, on the global list (comprising 180 countries in total) [20].

Country rankings in the CPI largely align with similar responses collected in 2024 through a Eurobarometer survey [21]. Although the CPI and the Eurobarometer survey are based on different methodologies and focus on different aspects of corruption, Finland, Denmark and Luxembourg stand out in both as countries where corruption is perceived to be rare. However, the Eurobarometer results present a more pessimistic view of corruption levels across the EU compared with the CPI. In all but four countries, at least half of respondents considered corruption a widespread national problem. For the EU as a whole, this translates into an average of 68% of respondents sharing this perception in 2024. Nevertheless, this share remains 8 percentage points below the 2013 value. The proportion of population who thinks corruption in their country is rare was 27% in 2024.

There is a notable relationship between the CPI and the perceived independence of the justice system. Countries with a high CPI ranking, such as Denmark, Finland, Sweden or Luxembourg, also show a high share of the population rating the independence of the justice system as ‘good’ (see Figures 10 and 12). Conversely, countries with less optimistic ratings of the justice system’s independence also tend to have lower CPI scores, for example Bulgaria and Croatia. As both indicators are based on people’s perceptions, however, a causal relationship between the effectiveness of the justice system and the occurrence of corruption cannot be inferred based on these data. Effective justice systems are nevertheless considered to be a prerequisite for fighting corruption [22].

Trust in EU institutions has fluctuated over the past few years

Confidence in political institutions is key for effective democracies. On the one hand, citizens’ confidence increases the probability that they will vote in democratic elections. On the other hand, it provides politicians and political parties with the necessary mandate to take decisions that are accepted in society.

Trust in three of the EU’s main institutions — the European Parliament, the European Commission and the European Central Bank — has fluctuated over the past two decades. Following a decline in trust across all three institutions in 2020, data from autumn 2024 show a resurgence, with 53% of the population expressing confidence in both the European Central Bank and European Parliament, and 51% in the European Commission [23]. Notably, this marks the first time since 2007 that more than half of Europeans have expressed trust in all three institutions. Throughout the years, the European Parliament has consistently been the most trusted of the three institutions surveyed.

The economic crisis may have played a role in the decline in trust in EU institutions observed between 2007 and 2015, while the COVID-19 pandemic might have influenced the drop in 2020. High inflation levels due to pressure on energy, food and other commodity prices because of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine might have caused a slight decline in trust in the EU Institutions in 2022 and 2023. However, surveys show that citizens tend to only have a general idea about the EU and lack a deeper knowledge of the role and powers of the EU institutions, making confidence in the EU more dependent on contextual information than on actual governance [24].

Main indicators

Standardised death rate due to homicide

This indicator tracks deaths due to homicide and injuries inflicted by another person with the intent to injure or kill by any means, including ‘late effects’ from assault (International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes X85 to Y09 and Y87.1). It does not include deaths due to legal interventions or war (ICD codes Y35 and Y36). The data are presented as standardised death rates, meaning they are adjusted to a standard age distribution to measure death rates independently of the population’s age structure.

Source: Eurostat (sdg_16_10)

Source: Eurostat (sdg_16_10)

Population reporting crime, violence or vandalism in their area

This indicator shows the share of the population who reported a problem with crime, violence or vandalism in their local area. This describes the situation where the respondent feels crime, violence or vandalism in the area to be a problem for the household, although this perception is not necessarily based on personal experience. The data stem from the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC).

Source: Eurostat (sdg_16_20)

Source: Eurostat (sdg_16_20)

Victims of trafficking in human beings

This indicator refers to victims of trafficking in human beings as defined under Article 2 of the Directive 2011/36/EU. A registered victim can be a person who has been formally identified as a victim of trafficking in human beings by the relevant formal authority in a Member State or a person who has met the criteria of the EU Directive but has not been formally identified by the relevant formal authority as a trafficking victim or who has declined to be formally or legally identified as trafficked.

Source: Eurostat (sdg_16_70)

Source: Eurostat (sdg_16_70)

General government total expenditure on law courts

This indicator refers to the general government total expenditure on law courts. It includes expenditure on the administration, operation or support of civil and criminal law courts and the judicial system, including enforcement of fines and legal settlements imposed by the courts. The operation of parole and probation systems, legal representation and advice on behalf of government or others provided by government in cash or in services are also taken into account. Law courts include administrative tribunals, ombudsmen and the like, but excludes prison administrations.

Note: y-axis does not start at 0.

Source: Eurostat (sdg_16_30)

Source: Eurostat (sdg_16_30)

Perceived independence of the justice system: very or fairly good

This indicator is designed to explore respondents’ perceptions about the independence of the judiciary across EU Member States, looking specifically at the perceived independence of the courts and judges in a country. Data on the perceived independence of the justice system stem from annual Flash Eurobarometer surveys, which started in 2016 on behalf of the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Justice and Consumers.

Source: European Commission services, Eurobarometer, Eurostat (sdg_16_40)

Source: European Commission services, Eurobarometer, Eurostat (sdg_16_40)

Corruption Perceptions Index

This indicator is a composite index based on a combination of surveys and assessments of corruption from 13 different sources and scores. It ranks countries based on how corrupt their public sector is perceived to be, with a score of 0 representing a very high level of corruption and 100 representing a very clean country. The sources of information used for the Corruption Perception Index (CPI) are based on data gathered in the 24 months preceding the publication of the index. The CPI includes only sources that provide a score for a set of countries or territories and that measure perceptions of corruption in the public sector. For a country or territory to be included in the ranking, it must be included in a minimum of three of the CPI’s data sources. The CPI is published by Transparency International.

Note: y-axis does not start at 0.

Source: Transparency International, Eurostat (sdg_16_50)

Source: Transparency International, Eurostat (sdg_16_50)

Footnotes

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (ilc_mddw06).

- ↑ See for example: Rader, N. (2017), Fear of Crime, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Criminology.

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (sdg_16_10).

- ↑ UNODC and UN Women (2023), Gender-related killings of women and girls (femicide/feminicide), United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, p. 6.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (crim_hom_vrel).

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (crim_hom_soff).

- ↑ For more information see Eurostat metadata on Crime and criminal justice (crim) and European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2014), Violence against women: an EU-wide survey, Main results, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, pp. 25–26.

- ↑ UNODC, Human Trafficking FAQs.

- ↑ European Commission (2021), EU Strategy on Combatting Trafficking in Human Beings, COM(2021) 171 final.

- ↑ UNODC (2022), Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 2022, p. 38.

- ↑ Eurostat (2025), Statistics Explained: Trafficking in human beings statistics.

- ↑ UNODC (2022), Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 2022, p. xi.

- ↑ Eurostat (2025), Statistics Explained: Trafficking in human beings statistics.

- ↑ Calculations based on Eurostat (crim_thb_vexp).

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (gov_10a_exp).

- ↑ European Commission (2024), Flash Eurobarometer 540, Perceived independence of the national justice systems in the EU among the general public, p. 3.

- ↑ Ibid, p. 4.

- ↑ Ibid, p. 7.

- ↑ Transparency International (2025), Corruption Perceptions Index 2024.

- ↑ European Commission (2024), Special Eurobarometer 548 on Citizens’ attitudes towards corruption in the EU in 2024, pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Also see European Commission (2017), European Semester Thematic Factsheet on Effective Justice Systems.

- ↑ European Commission (2024), Standard Eurobarometer 102, Public Opinion in the European Union, pp. 111–112.

- ↑ European Research Centre for Anti-Corruption and State-Building (ERCAS) & Hertie School of Governance (2015), Public integrity and trust in Europe, Berlin, p. 19; and Eurofound (2022), Fifth round of the Living, working and COVID-19 e-survey: Living in a new era of uncertainty, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

Explore further

Database

Thematic section

Publications

Further reading on peace, justice and strong institutions

- European Commission (2024), The 2024 EU Justice Scoreboard.

- European Commission (2024), Perceived independence of the national justice systems among the general public.

- European Commission (2024), Citizens’ attitudes towards corruption in the EU in 2024.

- UNODC and UN Women (2023), Gender-related killings of women and girls (femicide/feminicide.

- UNODC (2022), Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 2022.

Methodology

More detailed information on EU SDG indicators for monitoring of progress towards the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), such as indicator relevance, definitions, methodological notes, background and potential linkages can be found in the introduction as well as in Annex II of the publication ’Sustainable development in the European Union — Monitoring report on progress towards the SDGs in an EU context — 2025 edition’.

External links

Further data sources on peace, justice and strong institutions

- Eurostat, Crime and criminal justice statistics.

- Global statistics on crime, criminal justice, drug trafficking and prices, drug production, and drug use.

- Transparency International, Corruption Perceptions Index.

- World Bank, Worldwide Governance Indicators.