How does the EU make the impossible happen?

date: 10/11/2020

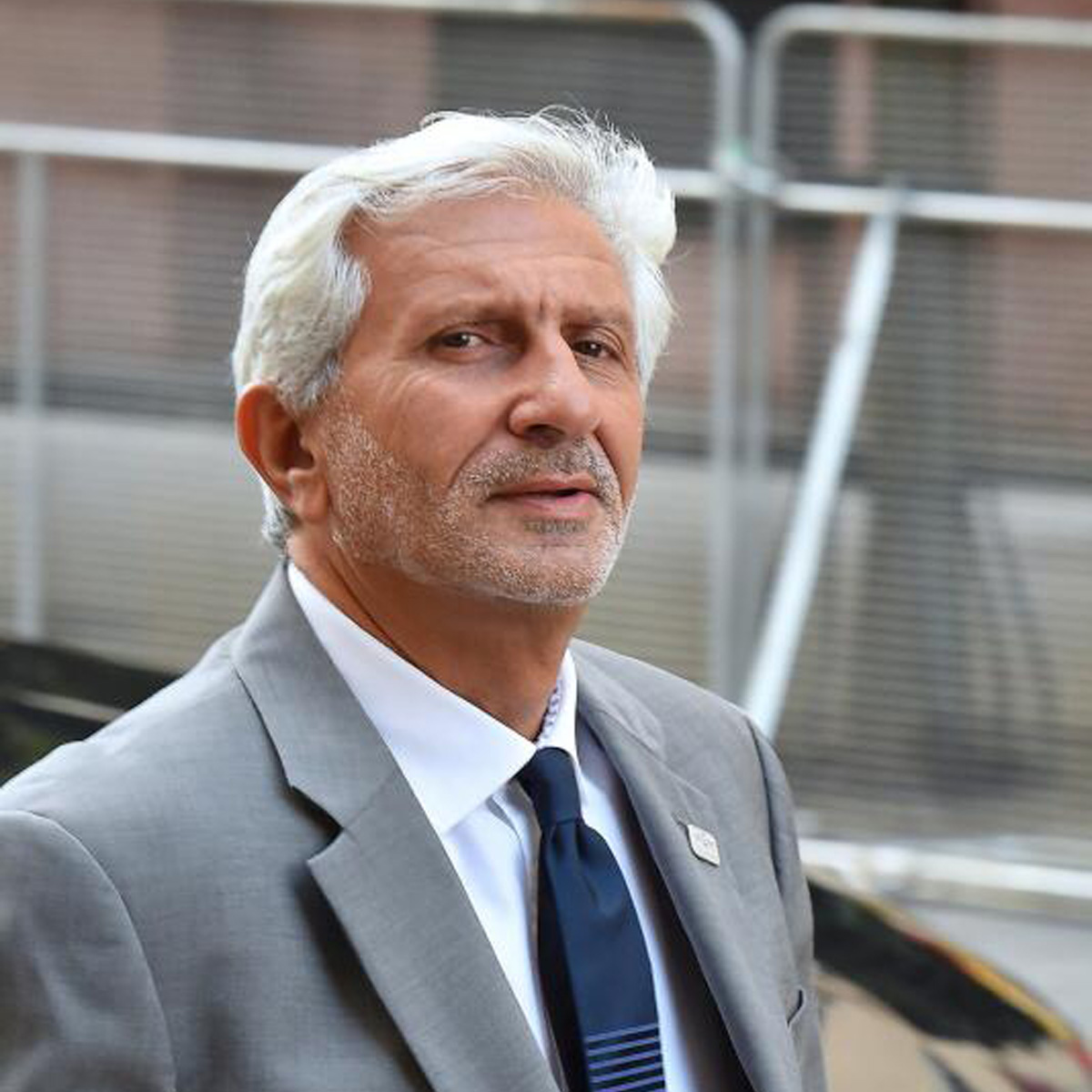

The countries of the EU have varying interests in foreign affairs, different historical backgrounds and uneven positions on the international stage. Still, they are often able to speak with one voice on external affairs. How is this possible? We asked Leonardo Schiavo*, the Council's Director-General for foreign affairs, enlargement and civil protection (RELEX).

In the last decade, the EU has been deciding jointly on more and more issues in foreign affairs. Why is this happening?

L.S. It's a consequence of the way global politics look today. The key protagonists on the international scene are continent-size countries, with huge economic and military assets and often a nuclear arsenal. None of the EU countries – even the largest economies and those which, historically, have been diplomatic heavyweights – would have sufficient leverage to face global superpowers on their own.

Next to counterparts such as the US, China and Russia, the united voice of 27 states, standing for 16% of global GDP and representing almost 450 million citizens, is clearly much louder than the voice of any single country.

In addition, each EU country brings its own special contribution to forging a common foreign policy. Some have closer links to the EU's eastern or southern neighbours, others have close relations with Mercosur countries, or with Africa. By sharing these specificities and acting together, we are stronger.

The most traditional tool of foreign policy is military power – something the EU doesn't have. What is at our disposal?

L.S. It is true that the EU's security and defence policy is still in an evolutionary phase. Surprisingly, if we add up the expenditure on defence of all the member states, we might end up spending more than the USA. Obviously, the level of coordination and interoperability between individual EU countries is not as advanced as to translate this amount into a single military capacity.

But the EU's ambition is to act as a security provider, rather than as a military power in the traditional sense of this expression. Since the EU as such lacks the kind of hard power available to some of the main global players, it has learned how to master and maximise the use of a combination of soft power tools. These include economic diplomacy, trade policy, development and humanitarian aid. And it works – globally we do have a real impact.

Climate diplomacy is a good example. Besides their primary purposes, the EU's trade agreements and development aid (areas where we are a real superpower) also serve as incentives for others to follow vital commitments on fighting climate change.

None of the sectoral global agreements (e.g. on climate, development, energy or digital policy) could have been crafted without the EU's participation. This is thanks to the size and advancement of the EU economy.

The European Council has the leading role in defining the direction of the EU's foreign and security policy. And usually all countries have to agree unanimously…

L.S. Decision-making in these areas is in the hands of the European Council and the Council. We need unanimity because these competences touch upon countries' sovereignty. Every country – even the smallest – has its say when it comes to foreign and security policy matters.

We have to strive for consensus on most issues. This explains why reaching an agreement is often laborious and occasionally even impossible, due to domestic politics or earlier bilateral commitments. The results of compromise solutions are, at times, understandably less ambitious than expected. But any joint action, under a common policy decision, is better than inaction.

Moreover, it takes time – and this is something we have to work on. The EU needs to speed up its decision-making process in the field of external action. Global politics move at a much greater pace these days, and those who cannot keep up with this new reality could be left behind.

What are the greatest EU successes in foreign policy that you have worked on?

Success in foreign and especially security policy is often less about making things happen and more about making things not happen, e.g. preventing a war, or a major humanitarian crisis. I have seen many such successes go untold.

The Iran nuclear agreement, on the other hand, is an example of visible conflict prevention. The EU started working on it right after the war in Iraq. That conflict had been a disaster for EU foreign policy because of the deep divisions it generated. Some member states openly opposed the US intervention, while others joined the allied forces' coalition.

The EU learned its lesson from Iraq. We wanted to do everything possible to avoid yet another military conflict in the region and we realised that speaking with one voice was essential if we were to do so.

After years of diplomatic action – first negotiations, then pressure (including sanctions) and then more negotiations – the agreement was finally signed in 2015. The EU, together with the permanent members of the UN Security Council and Germany, was one of the signatories of this agreement, having acted as the coordinator of the negotiating efforts with Iran.

The fate of this agreement currently hangs in the balance, since the US under Trump decided to withdraw from the deal. The EU is trying hard to save the agreement. Without our involvement throughout the years, there would have been a serious risk of another major war in the Middle East.

-

Established in 1993 by the Treaty on European Union

-

Strengthened by further treaties – especially the Treaty of Lisbon (2009)

-

Designed to resolve conflicts and foster international understanding

-

The European Council sets guidelines for the foreign and security policy

-

These guidelines are then implemented by the Foreign Affairs Council

-

Most foreign and security policy decisions require the agreement of all EU countries

-

The EU has a diplomatic corps called the European External Action Service

-

The EU has no standing army, but can send missions to the world's trouble spots. Such missions consist of ad-hoc forces contributed by EU countries.

* Leonardo Schiavo

Director-General for foreign affairs, enlargement and civil protection (RELEX) since 2011.

He has been dealing with foreign relations throughout most of his career, holding management positions in both the Commission and the Council. Former Chief of Cabinet of the Italian Minister for International Trade and former head of the Private Office of Javier Solana (the EU's first High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy).