How not to get lost in translation?

date: 08/10/2020

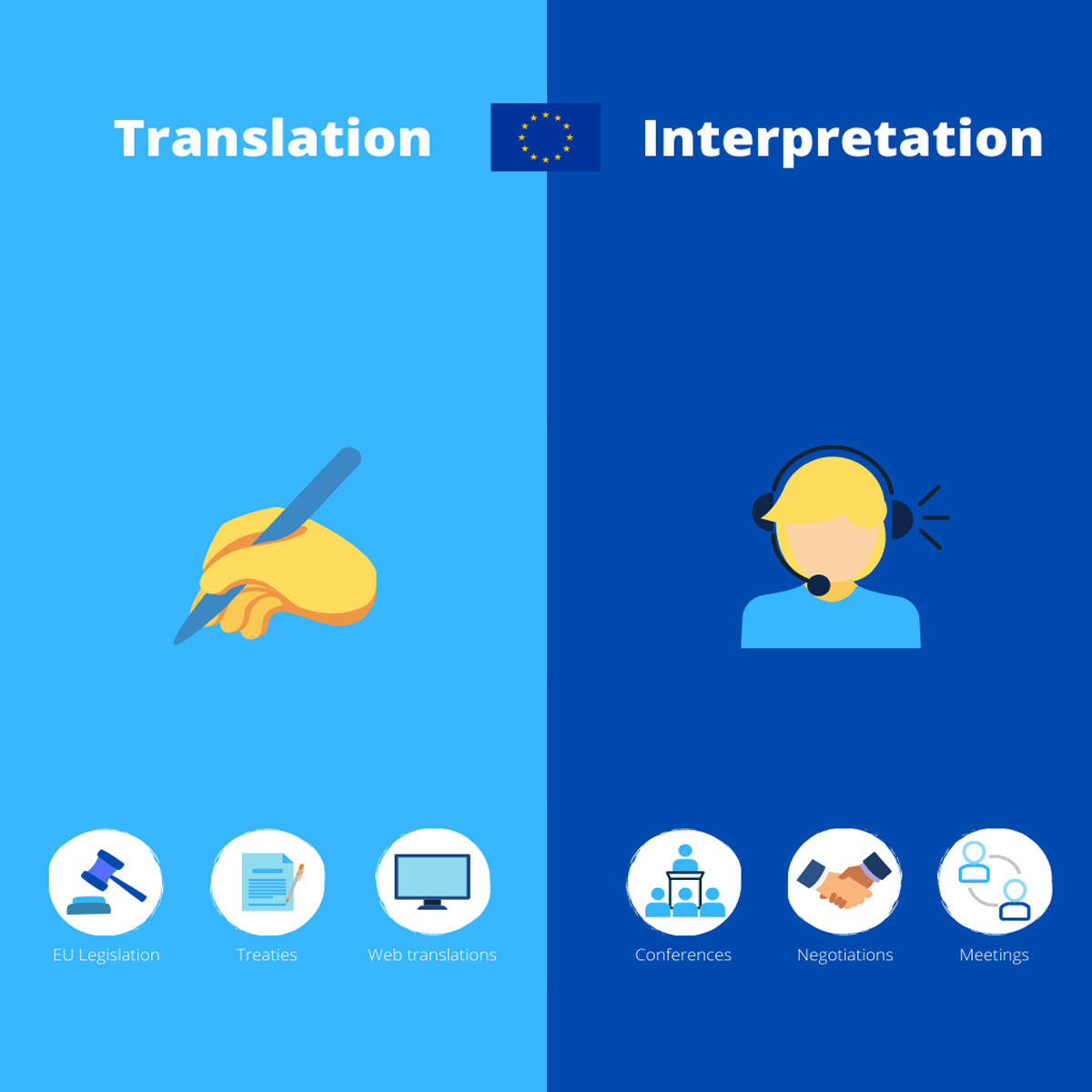

Interpretation and translation – what’s the difference? An interpreter orally translates the spoken word, while a translator deals with what is written down. The work of both is indispensable for the smooth running of the European Council (also called EUCO or the EU summit).

Read between the lines

For both translators and interpreters, preparation begins long before the day of the European Council. They read preparatory documents and background notes, but also media coverage about the topics to be discussed during the EUCO. Keeping up to date on European and international politics is a must.

Approximately two weeks before the EUCO, translators receive the first draft of the conclusions for translation. Here, every word matters. They analyse the text and discuss it among themselves and with the diplomats who have drafted it. Translators need to understand the political statements that hide behind each paragraph. This process is repeated with every new draft of the conclusions until the final version.

Why is translating a few pages of text so complicated? The summit conclusions often describe delicate diplomatic matters in a balanced way. Each linguistic version must reflect the fine-tuned subtleties and nuances correctly.

Read my lips

During the European Council, both translators and interpreters work in shifts. For interpretation, there are usually three teams of two or three interpreters for each of the 23 languages. If discussions take longer than expected (which is often the case), the teams rotate. Altogether, there are about 200 interpreters involved.

Each of them interprets from a minimum of three languages into his or her main language – usually a mother tongue. Record holders interpret from up to 10 languages or into up to three active languages.

Interpreters are rarely in direct contact with the people who listen to them. However, European leaders often thank them for their work by waving to the booths or showing thumbs up. Sometimes a prime minister or president might also appear in the corridor leading to the interpreters’ booths. What for? Usually to pick up a call – this is the nearest quiet spot to their meeting room.

Coping with COVID-19

Interpreters admit that limitations caused by the pandemic remain challenging – especially during videoconferences. The image and sound quality leaves much to be desired. Facial expressions and body language are also less visible during online meetings, which is a serious inconvenience as both play an important role during interpretation.

Before COVID-19, there were three interpreters sitting in each booth. Now there are only two, separated by a protective Plexiglas divider. They need to be able to make eye contact to communicate – e.g. to signal that a colleague needs to take over or help with a difficult term.

The new reality impacts the way translators work, too. For the EUCO, there are usually two teams, consisting of three to five people per language (depending on the complexity of the meeting). Normally, they would be gathered in a large room called the multipurpose room (or panic room). Each language had its own table, and translators could talk freely to each other to discuss the most suitable wording. Now, they are still all in one building, but for safety reasons they have to communicate by phone and avoid direct contact.

Leaks? Never. Pressure? Often

Neither interpreters nor translators are allowed to talk about the conversations held inside the meeting room or the documents they work on. They take this confidentiality clause very seriously.

So, where do the leaks you read about in newspapers come from? Journalists usually get their scoops from diplomats who have access to draft documents and to people in the room.

What also sometimes happens is that a national delegation suggests a certain wording for a translation. A helping hand? Not exactly – more like an attempt to achieve through translation what they didn’t manage to achieve at the negotiating table. So translators have to stay vigilant.

Don't get lost in translation!