Quality of life indicators - governance and basic rights

Data from October 2021

Planned article update: June 2024

Highlights

In 2019, the gender pay gap averaged 11.1 percentage points across the whole of the EU, with the smallest gap in Lithuania (1.7 pp) and the widest gap in Italy (19.9 pp).

In 2015, active participation in civil society in the EU varied from almost a third of the population in Sweden to around 2 % in Cyprus.

Active participation in civil society, 2015 (%)

This article is part of a Eurostat online publication that focuses on Quality of life indicators, providing recent statistics for the European Union (EU). The publication presents a detailed analysis of various dimensions that can form the basis for a more in-depth analysis of the quality of life, complementing gross domestic product (GDP) which has traditionally been used to provide a general overview of economic and social developments.

The focus of this article is the seventh dimension — governance and basic rights — of the nine quality of life indicators dimensions that form part of a framework endorsed by an expert group on quality of life indicators. Civil society, a respect for human rights and the rule of law, as well as accountable government are some of the hallmarks of modern democracies which impact on the quality of life led by European citizens; many would argue that simply paying lip service to such rights or embedding them in law is insufficient without their effective implementation. However, to do so, public institutions — such as the police, the judicial system or civil servants — need to be free from corruption, political interference or prejudice. Governance issues — such as institutional checks and balances, transparency and freedom of access to information — are often promoted as areas which need to be addressed to ensure accountability. By doing so, it is likely that citizens will develop an enhanced level of trust in institutions and the quality of governance.

Full article

Active citizenship

Aside from these institutional issues, the quality of an individual’s life may also be affected by their own participation in civil society. There is a wide range of indicators that may be used to measure participative public engagement including statistics on turnout in elections, membership of political parties or trade unions, or participation in civil society groups/organisations. Many of these forms of engagement are characterised by a desire to make a contribution to local, national or international solidarity, for example, through campaigning, donating or volunteering.

Active participation in cultural and social life is thought to be closely linked to an individual’s quality of life, as it may influence both cultural and social capital. Within the context of the 2015 ad-hoc module of the EU’s statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC), active citizenship was defined to include activities such as: participation in a political party or a local interest group; participation in a public consultation; peaceful protest including signing a petition; participation in a demonstration; writing a letter/e-mail to a politician; writing a letter/e-mail to the media. Note that the act of voting is not considered as active citizenship, as it is compulsory in some of the EU Member States.

In 2015, 12.5 % of adult men in the EU — defined here as those aged 16 and over — were active citizens, slightly higher (0.8 percentage points) than the share for women (11.7 %). There was a considerable degree of variation in the degree of active citizenship across the EU Member States: almost one third (31.3 %) of the adult population in Sweden were active citizens in 2015, while in the Netherlands, France and Finland the share of active citizens was between one quarter and one fifth. At the other end of the range, less than 1 in 10 of the adult population were active citizens in a majority (19 out of 27) of the Member States. Of these, there were seven that recorded shares below 5.0 %, principally located in eastern Europe — Hungary, Czechia, Bulgaria, Romania and Slovakia — but also including Belgium and Cyprus, where the lowest level of active citizenship was recorded (2.1 %).

Figure 1 shows that the proportion of active citizens was generally higher for men than it was for women across the EU Member States. In 2015, there were only four exceptions to this pattern: Lithuania, France, Sweden and Finland. It is interesting to note that with the exception of Lithuania, each of these had high overall rates of active citizenship (three out of the four highest rates). Finland had the widest gender gap for active citizenship, as the share of women who were active citizens was 4.4 percentage points higher than the corresponding share for men. By contrast, the gender gap was generally in favour of men and among the 23 Member States where this was the case, the largest gender gaps were recorded in Greece (4.0 points), Austria (3.3 points), Luxembourg (2.8 points) and Belgium (2.7 points).

(% of men/women aged 16 and over)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_scp19)

Young women and elderly men more likely to be active citizens

The information presented in Figure 2 extends the analysis by taking account of age: in 2015, young women (aged 16-24) in the EU were more likely than young men to be active citizens; while there was almost parity between the sexes among the core working-age population (25-64 years); however, elderly men (aged 65-74 years) were more likely than elderly women to be active citizens. Although this pattern was not reproduced in each of the EU Member States it was relatively common to find that the lowest share of active citizenship among women was recorded among the elderly, whereas the opposite was true for men, with men aged 65-74 years often recording the highest share of active citizenship among any of the different age classes.

A closer analysis reveals that Sweden recorded the highest rates of active citizenship in 2015, irrespective of age or sex; note that the share of elderly women from France who were active citizens was the same as the proportion recorded in Sweden. Gender gaps for active citizenship were often more pronounced for either young adults or the elderly than they were for the core working-age population (where rates of active citizenship were typically low for both men and women, likely reflecting work and family commitments for this age group). The share of young adult women who were active citizens was 10.4 and 9.1 percentage points higher than the share for young men in Sweden and Finland. Among the elderly population, Finland and Estonia were the only EU Member States to record a slightly higher share of active citizens among elderly women than among elderly men. By contrast, in the remaining Member States where elderly men were more active, the gender gap widened to 7.4 points in Greece, 7.6 points in Slovenia and peaked at 8.0 points in Luxembourg.

(% of each age/sex group)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_scp19)

High earners twice as likely as low earners to be active citizens

The final analysis in this section focuses on active citizenship by income situation (see Figure 3). In 2015, the share of the EU population who were active citizens was considerably higher among the subpopulation composed of the fifth income quintile (in other words, the top 20 % of highest earners; 17.2 %) than it was for the first income quintile (the bottom 20 % of lowest earners; 9.0 %); in other words, the highest earners in the EU were almost twice as likely as the lowest earners to be active citizens.

This pattern — a higher share of active citizens among the fifth rather than the first income quintile — was repeated in each of the EU Member States, although there was almost no difference in the level of active citizenship between these two subpopulations in Denmark and the difference was also relatively narrow in Sweden, the Netherlands, Finland and Malta. By contrast, people in Cyprus in the fifth income quintile were 7.5 times as likely to be active citizens as those in the first income quintile, while in Lithuania and Bulgaria the highest earners were 5.0 and 4.8 times as likely as those with the lowest earnings to be active citizens. These figures suggest that the highest earners in society often have more interest or lower barriers to participate actively in cultural and social life, while people with the lowest incomes tend to be less active.

(% of population aged 16 and over)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_scp20)

Voter turnout

According to a report commissioned by the European Commission's Directorate-General for Communication, there has been a steady decline in voter turnout at European Parliament elections, with the share of people casting a ballot (relative to the total number of eligible voters) falling during seven consecutive elections from a high of almost 62 % in 1979 to 42.5 % in 2014. However, in the latest election, the voter turnout increased again to 50.7%. It is interesting to note that voter turnout was particularly low among the younger generation and was relatively high among the elderly.

Turnout is often used as a proxy for democratic legitimacy: across the EU it averaged 50.7 % in the 2019 European Parliament elections (see Map 1), ranging from highs of 88.5 % and 84.2 % in Belgium and Luxembourg (note that voting is compulsory in Belgium, Greece, Cyprus and Luxembourg) down to less than one quarter of all eligible voters in Slovakia (where the lowest level of voter turnout was recorded, at 22.7 %).

(% of eligible voters casting a ballot)

Source: https://europarl.europa.eu/election-results-2019/en/turnout/

Trust in the political and legal systems

The considerable variations witnessed in voter turnout may reflect, at least to some degree, the trust that people have in political systems. In 2013, on a scale of 0-10 (with 0 being the lowest and 10 the highest), the average rating given to trust in the political systems of the EU was 3.5; this may be compared with a value of 4.5 which was recorded for trust in the legal system.

The highest levels of trust in political systems were recorded in the Nordic Member States, Malta and the Netherlands in 2013; none of the other EU Member States recorded a score that was above 5.0. At the other end of the range, aside from Slovenia (1.8) and Bulgaria (2.6), the lowest levels of trust in political systems were recorded across southern Member States (Cyprus, Italy, Greece, Spain and Portugal); the lowest average rating was recorded in Portugal (1.7).

As was the case for trust in political systems, the highest levels of trust in legal systems were also recorded in the Nordic Member States and the Netherlands (where ratings were higher than for political systems). At the other end of the range, the lowest levels of trust in legal systems among the EU Member States were recorded in Croatia, Spain, Bulgaria, Portugal and Slovenia. Note that the level of trust in the Maltese legal system was lower than for the political system, whereas elsewhere the reverse was true.

High earners have more trust in political and legal systems

An analysis by income situation is presented in Figure 4: it highlights that people in the fifth income quintile generally had a higher degree of trust in political systems (an average score of 3.9 across the EU in 2013) than people in the first income quintile (3.2). This pattern — a lower score among people in the first rather than the fifth income quintile — was repeated in each of the EU Member States, with the exception of Malta, where there was no difference between these two subpopulations. The gap was widest in Germany, as people in the fifth income quintile gave an average rating of 5.8 to the political system, compared with a score of 4.2 for people in the first income quintile; the next largest gaps were recorded in Ireland and Latvia.

The picture was even clearer when analysing the trust that people had in legal systems, with those in the fifth income quintile systematically recording a higher level of trust than those in the first income quintile. These results may be somewhat disconcerting insofar as legal systems are generally intended to protect the rights of all citizens, yet there appears to be a clear divide in the degree of trust afforded to legal systems by citizens belonging to different income quintiles. This divide was widest in Germany, where people in the fifth income quintile gave an average rating of 6.2 to the legal system, compared with a score of 4.6 for people in the first income quintile; the next largest gaps were recorded in Estonia and Hungary.

(rating, 0-10)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_pw04)

Equal rights

The functioning of democratic institutions and civil society shape an important dimension in the quality of life for European citizens. The rule of law should ideally be based on unambiguous legal provisions that provide for the equal treatment of all citizens, whether considered in terms of gender, sexual orientation, disability, race, ethnicity, religion or other characteristics. That said, a range of different surveys across the EU reveal that a relatively high proportion of Europeans consider various forms of discrimination to be common, as can be seen from the specialized surveys on disadvantaged populations coordinated by the Fundamental Rights Agency.

Gender employment gap persists despite increase in female labour market participation

One example is discrimination in labour markets, be it in relation to the degree of female participation or the average earnings that women receive compared with men. The indicators used within the Quality of life indicators framework to measure this are the gender employment gap and the gender pay gap. Most academics agree that self-perceived quality of life measures are enhanced when more women work, perhaps as a result of increasing levels of empowerment, economic security and social inclusion. There is a wide range of policy measures which might be considered to promote higher degrees of female participation, including, the provision for more childcare services, encouraging greater flexibility in terms of parental leave, or promoting workplace cultures that are supportive of flexible work arrangements. Narrowing the gender employment gap — in other words, the difference between the employment rates of working-age men and women (defined here as those aged 20-64) — is a headline indicator of the European Pillar of Social Rights, which is the EU scoreboard for ensuring that the rights of all EU citizens are respected.

While there has been a general increase in female labour market participation during recent decades, the gap between the sexes remains persistent and in 2020 female employment rates were systematically lower than those of men in all EU Member States (see Map 2). In 2020, this gap averaged 11.1 percentage points across the whole of the EU, with relatively small differences between the employment rates of the sexes in Lithuania (1.7 points), Finland (2.9 points), Latvia (3.8 points) and Sweden (4.9 points). On the other hand, the gender employment gap was much wider in some of the southern EU Member States, as it peaked at 19.9 points in Italy; these countries are characterised by a more traditional gender division of labour, where women perform more unpaid work such as looking after the home, taking care of a smallholding, or providing care to both younger and older generations and are therefore not available for paid work.

(percentage points; difference between the employment rates of men and women aged 20-64)

Source: Eurostat (lfsi_emp_a)

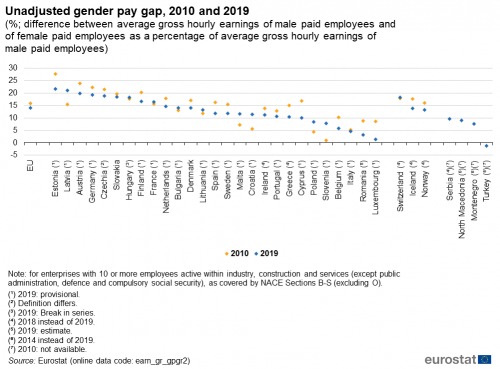

The gender pay gap

The gender pay gap, in other words, the difference between men’s and women’s average gross hourly earnings, is an alternative indicator that highlights the differences in earnings between the two groups. This indicator is calculated in an unadjusted form (it is the difference between average gross hourly earnings of male paid employees and of female paid employees as a percentage of average gross hourly earnings of male paid employees) and it may be influenced by the gender employment gap; typically, when the gender employment gap is wide then the gender pay gap is often quite narrow — this may reflect, among others, a relatively high proportion of low-qualified women not participating in the labour market. On the other hand, differences in pay between the sexes may also reflect: a lack of equal opportunities in education; a lack of equal treatment/opportunities in the workplace; societal constraints, such as gender role expectations, for example, women being much more likely to work part-time or to take career breaks because of caring responsibilities. As such, the gender pay gap reflects a broad range of issues that extend beyond the concern to have equal pay for equal work.

Official statistics show that, on average, the unadjusted gender pay gap 15.8 % in the EU in 2010, before following an upward pattern as the gap widened to 16.4 % by 2012. Thereafter, the unadjusted gender pay gap for the EU either remained unchanged or fell during four consecutive years and stood at 14.1 % in 2019.

A more detailed analysis reveals that the unadjusted gender pay gap reached its highest levels in Estonia (21.7 %) and Latvia (21.2 %), while men were, on average, paid at least 10 % more than women in the majority of the remaining EU Member States. At the other end of the range, there were six Member States where the unadjusted gender pay gap was in single digits. Three of these were eastern Member States — Poland, Slovenia and Romania — and they were characterised by relatively low levels of part-time employment, as their shares of part-time employment were consistently below 10 % (compared with an EU average of 17.8 %. The other three Member States with the smallest unadjusted gender pay gaps were Belgium, Italy and Luxembourg; the smallest gaps — within the range of 3.0-5.0 % — were recorded in Italy, Romania and Luxembourg (see Figure 5).

(%; difference between average gross hourly earnings of male paid employees and of female paid employees as a percentage of average gross hourly earnings of male paid employees)

Source: Eurostat (earn_gr_gpgr2)

Gender pay gap lower for younger employees

The unadjusted gender pay gap is generally much lower for younger employees than it is for older members of the workforce across almost all of the EU Member States. This may reflect, at least in part, changes in societal norms, such as postponing first childbirth until later in life or choosing not to have children, which may allow more women the opportunity to continue their studies into their twenties and/or to start a career. That said, the unadjusted gender pay gap usually increases as a function of age (see Figure 6), which may be linked to a higher proportion of women (than men) taking time out of their careers or changing their working hours/responsibilities in order to care for children, but may also reflect a lack of equal opportunities with fewer women occupying management roles. While the average hourly earnings of both men and women generally rise with age, men’s pay usually grows at a faster pace than the pay received by women, making it commonplace for much wider unadjusted gender pay gaps to be observed in middle age and for older people who are approaching retirement.

In 2019, half (14 out of 21; no data available for Germany, Estonia, Ireland, Greece, Luxembourg and Austria) of the EU Member States recorded their lowest unadjusted gender pay gap (in favour of men, or highest in favour of women) among people aged less than 25 years. By contrast, in Cyprus this category registered the second highest gender pay gap.

In cases where the lowest unadjusted gender pay gap (in favour of men, or highest in favour of women) was not recorded among people aged less than 25 years, it was common to find this for the highest age class, namely, among people aged 55-64 years. This pattern was reproduced in five of the EU Member States and in one of these — Romania — the average earnings of women were higher than those for men.

By contrast, in the remaining two Member States for which data are available — Cyprus and the Netherlands — where the lowest unadjusted gender pay gaps (in favour of men, or highest in favour of women) were not in either of the two age classes discussed above, the lowest gaps were recorded among people aged 25-34 years.

With the exception of Cyprus (as noted above), much wider unadjusted gender pay gaps tended to be recorded after the age of 35; this coincides with the period by when many women may have taken a career break in order to raise a family. Between the ages of 35 and 44, the unadjusted gender pay gap rose to at least 20.0 % in Slovakia, Hungary, Latvia and Czechia, where a peak of 23.3 % was recorded. For people aged 45-54 years, there were three Member States (Czechia, Slovakia and Finland) where the unadjusted gender pay gap was at least 20.0 %, with equally three Member States (France, Finland and the Netherlands) for people aged 55-64 years.

(%; difference between average gross hourly earnings of male paid employees and of female paid employees as a percentage of average gross hourly earnings of male paid employees)

Source: Eurostat (earn_gr_gpgr2ag)

Conclusions

Active citizenship is generally more common in northern and western EU Member States: at least one fifth of the adult populations of Sweden, the Netherlands, France and Finland were active citizens in 2015. These patterns were in many cases driven by higher degrees of active participation among women (in general) and men post-retirement (aged 65-74 years). Those Member States characterised by relatively high degrees of activism — participation in political or local interest groups, peaceful protests or campaigns — also tended to record some of the highest levels of voter turnout and trust in political and legal systems, suggesting that participatory and pluralistic democracies may empower the public.

The functioning of democratic institutions and the rule of law should provide for the equal treatment of all citizens. However, there remain considerable inequalities across the EU which may be linked to characteristics such as gender, sexual orientation, disability, race, ethnicity or religion. Although there is some evidence that the gender pay gap in the EU has narrowed somewhat in recent years, men continued to be paid an average of 14.1 % more than women in 2019.

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

The material presented in this article regarding active citizenship and trust in institutions is derived from EU-SILC. The first section of the article is based on the results from a 2015 ad-hoc module on social/cultural participation and material deprivation. This module included 15 variables on social and cultural participation. For the purpose of the ad-hoc module, active citizenship was defined as: participation in the activities of a political party or a local interest group; participation in a public consultation; peaceful protest including signing a petition; participation in a demonstration; writing a letter/e-mail to a politician; writing a letter/e-mail to the media.

The information presented for trust in political and legal systems is also taken from EU-SILC. More specifically, it comes from a 2013 ad-hoc module on well-being. These indicators refer to the respondent’s opinion/feeling about the political or legal system. For the former this covers institutions, interest groups (such as political parties, trade unions), and the relationships between those institutions and the political norms/rules that govern their functions. For the legal system it covers all aspects related to interpretation and enforcement of laws.

Data regarding voter turnout is made available by the European Parliament's voter turnout report. This information may be used to measure citizens’ participation in EU, national or local public affairs. Turnout figures refer to the share of eligible voters who participate in an election; this includes people who cast a blank or invalid ballot paper. Note that in Belgium, Greece, Cyprus and Luxembourg, voting is compulsory.

The statistics that are presented on the gender employment gap are derived from the EU’s labour force survey (EU-LFS). This indicator shows the difference between the employment rates of men and women aged 20-64, where the employment rate is calculated by dividing the number of persons in employment by the total population of the same age group.

The final set of information that is shown is derived from the structure of earnings survey (SES). The unadjusted gender pay gap represents the difference between average gross hourly earnings of male paid employees and of female paid employees as a percentage of average gross hourly earnings of male paid employees. Note that this information is presented for enterprises with 10 or more employees within industry, construction and services (excluding public administration, defence and compulsory social security), as covered by NACE Sections B-S (excluding Section O). Note also that as an unadjusted indicator, the gender pay gap provides an overall picture of the differences between men and women in terms of pay; it measures a concept which is broader than equal pay for equal work, as part of the earnings difference can be explained by individual characteristics of employed men and women and by sectoral and occupational differences between the sexes.

Context

The quality of democratic institutions, civil society and political culture generally constitutes an important dimension of the quality of life experienced by European citizens. The protection of human rights, the rule of law, transparency, accountability, and the elimination of discrimination and corruption are all reflected in our levels of satisfaction with, and trust in, institutions. Moreover, active citizenship and participation in civic society, is a fundamental aspect linked to an individual’s quality of life, linked to the accountability of governments and public institutions.

The importance of human rights is highlighted in Article 2 of the Treaty on European Union, which states that ‘The Union is founded on the values of respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights, including the rights of persons belonging to minorities. These values are common to the EU Member States in a society in which pluralism, non-discrimination, tolerance, justice, solidarity and equality between women and men prevail’.

The EU Charter of Fundamental Rights brings together in a single document the fundamental rights protected in EU law for six different areas: dignity, freedom, equality, solidarity, citizens’ rights, and justice. The Charter became legally binding with the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon in December 2009. In the area of discrimination, there are two long-standing Directives (Racial Equality Directive and Employment Framework Directive), and in July 2008 the European Commission adopted a Communication (COM(2008) 420 final) that presented a comprehensive approach to stepping up action against discrimination and for promoting equal opportunities.

During the period 2015-2017 there was a wide debate around the theme of ‘social Europe’ between EU institutions, Member States, social partners, civil society and citizens. Developments in this policy area centered on a new pillar of social policy, designed to take account of the changing realities in the world of work and to serve as a compass for renewed convergence within the euro area. In November 2017, the European Pillar of Social Rights was proclaimed during a summit for fair jobs and growth that took place in Gothenburg, Sweden. It aims to deliver fairness and social justice through new and more effective rights for citizens (the social acquis) and has three main categories covering 20 different principles that are spread over policy areas such as housing, education, social or health care, and employment:

- equal opportunities and access to the labour market;

- fair working conditions;

- social protection and inclusion.

Although the initiative is primarily conceived for the euro area, it is open to all EU Member States wishing to participate.

The Europe for Citizens (EFC) programme, aims to encourage direct participation of citizens within EU affairs, promoting dialogue between the EU institutions, civil society organisations and municipalities. The programme has been running since 2004 and for its 2014-2020 programme period it is focusing on actively involving European civil society in shaping EU policy (civil dialogue), as well as enhancing European citizens’ awareness of remembrance and the history of the EU.

In 2011, the European Commission launched the European equal pay day which is an annual event to raise awareness of the average wage gap between men and women. The date of this event varies every year depending on the average gender pay gap across the EU and in 2017 was fixed as 3 November, the date upon which women effectively stopped getting paid compared with their male colleagues.

Direct access to

- All articles on quality of life

- Quality of life indicators (online publication)

- Earnings (t_earn)

- Gender pay gap in unadjusted form (sdg_05_20)

- Quality of life, see:

- Material living conditions (qol_mlc)

- Productive or other main activity (qol_act)

- Health (qol_hlt)

- Education (qol_edu)

- Leisure and social interactions (qol_lei)

- Economic security and physical safety (qol_saf)

- Governance and basic rights (qol_gov)

- Natural and living environment (qol_env)

- Overall experience of life (qol_lif)

- EU SILC ad-hoc modules (ilc_ahm)

- 2015 — Social and cultural participation (ilc_scp)

- 2013 — Personal well-being indicators (ilc_pw04)

- LFS main indicators (lfs_emp_a)

- Employment and activity — LFS adjusted series (lfsi_emp)

- Employment and activity by sex and age - annual data (lfsi_emp_a)

- Employment and activity — LFS adjusted series (lfsi_emp)

- Earnings (earn), see:

- Gender pay gap in unadjusted form (earn_grgpg)