Archive:Urban Europe — statistics on cities, towns and suburbs — tourism and culture in cities

Data extracted in February–April 2016

This Statistics Explained article has been archived on 4 December 2020.

Highlights

In 2014, half of the number of bed places in tourist accommodation establishments in the EU were located in rural areas, while towns and suburbs accounted for one third and cities for one fifth.

(per 1 000 residents)

Source: Eurostat (urb_ctour)

This chapter is part of an online publication that is based on Eurostat’s flagship publication Urban Europe — statistics on cities, towns and suburbs (which also exists as a PDF).

Definitions of territorial units

The various territorial units that are presented within Urban Europe — statistics on cities, towns and suburbs are described in more detail within the introduction. Readers are encouraged to read this carefully in order to help their understanding and interpretation of the data presented in the remainder of the publication.

Full article

Tourism and culture in cities

The European Union’s (EU’s) cultural heritage is rich and diverse: it includes tangible assets such as historic towns and cities; natural and archaeological sites; museums and monuments; literary, musical and art works; as well as intangible attributes that are preserved through customs, traditions, folklore and linguistic diversity.

Whether for a short break or as a day trip within a longer holiday, many holidaymakers visit towns and cities. However, urban tourism is complex and the motivation of tourists is diverse, including for example: cultural tourism; gastronomic or oenological tourism; educational tourism; religious tourism; or volunteer tourism.

Tourism within Europe continues to grow: estimates suggest that it accounts for around one tenth of the EU 28’s gross domestic product (GDP). Growth in the number of tourists has been fuelled by mass-market tourism resulting from increases in living standards. International tourist numbers have been given a boost by the development of low-cost air travel which has encouraged many tourists to venture further afield and more often, for example, providing a stimulus for short-stay/weekend breaks in a range of city destinations.

However, in keeping with many aspects of urban development, tourism is a paradox, insofar as an increasing number of tourists in some towns and cities has resulted in congestion/saturation which may damage the atmosphere and local culture that made them attractive in the first place; it should be noted that this is not limited to urban tourism. Furthermore, while tourism has the potential to generate income which may be used to redevelop/regenerate urban areas, an influx of tourists can potentially lower the quality of life for local inhabitants, for example, through: higher levels of pollution and congestion; new retail formats replacing traditional commerce; increased prices; or increased noise. Venezia (Italy) and Barcelona (Spain) are two of the most documented examples of such issues. <sesection>

<sesection>

Tourism

In 2014, the capacity of tourist accommodation establishments, as measured by the number of bed places in the EU-28, reached almost 31 million. An analysis by degree of urbanisation reveals that almost half (46.4 %) of these were located in rural areas, while towns and suburbs accounted for 31.2 % and cities for 22.4 %. During the period 2012–14, the number of bed places in the EU-28 rose by 3.9 %, largely driven by a rapid expansion in cities (up 10.0 %), while growth rates were more modest for towns and suburbs (3.2 %) and rural areas (1.3 %).

Europe is the world’s no. 1 tourist destination

EU policymakers aim to maintain Europe’s position as a leading tourism destination, safeguarding and enhancing Europe’s cultural heritage, while maximising the contribution that tourism and culture can make to economic growth and employment.

The competitiveness of the activities involved in tourism is closely linked to economic, socio-cultural, and environmental sustainability, as outlined in a European Commission Communication titled ‘Agenda for a sustainable and competitive European tourism’ (COM(2007) 0621 final), which proposes an integrated approach to the challenges of sustainable tourism, including: preserving natural and cultural resources; limiting negative impacts at tourist destinations; promoting the well-being of the local communities; reducing the seasonality of demand; limiting the environmental impact of tourism-related transport; making tourism accessible to all; improving the quality of tourism jobs.

In June 2010, the European Commission adopted a Communication titled, ’Europe, the world’s No. 1 tourist destination — a new political framework for tourism in Europe’ (COM(2010) 0352 final), which set out a strategy for EU tourism. Four priorities were identified, namely to:

- stimulate competitiveness;

- promote the development of sustainable, responsible, and high-quality tourism;

- consolidate Europe’s image as a collection of sustainable, high-quality destinations;

- maximise the potential of the EU’s financial policies for developing tourism.

To enhance Europe’s position as a leading tourist destination, the European Commission ran its first international tourism campaign during 2012–14, ‘Europe, whenever you’re ready’, designed to encourage international tourists to discover Europe, highlighting its diverse cultural and natural heritage.

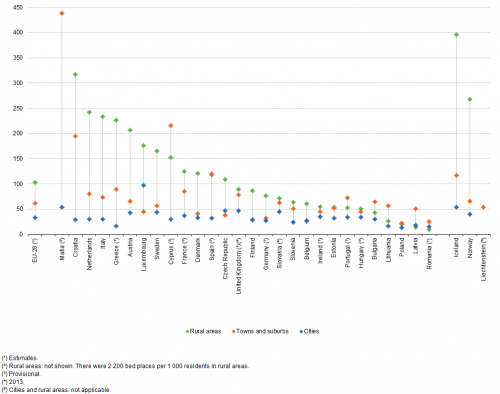

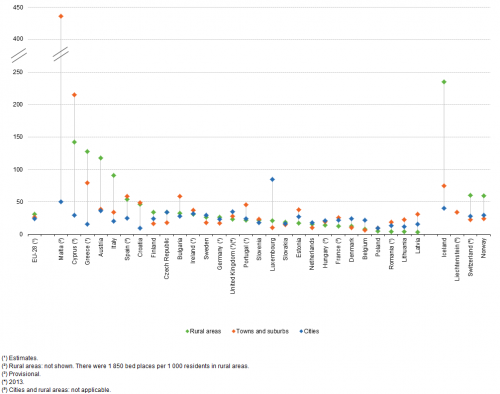

The most popular form of tourist accommodation in cities was hotels

Figure 1 presents the total number of bed places in tourist accommodation establishments relative to the resident population. While there were 103.0 bed places per 1 000 residents in rural areas of the EU-28, the corresponding ratios were much lower in towns and suburbs (61.4) and cities (32.8). Latvia and Romania were the only EU Member States where the number of bed places relative to the resident population was higher in cities than it was in rural areas, while Luxembourg and the Czech Republic were the only Member States where the ratio was significantly higher in cities than in towns and suburbs (although Belgium and Finland also reported slightly higher rates for cities).

(per 1 000 residents)

Source: Eurostat (tour_cap_natd), (ilc_lvho01) and (demo_gind)

The different types of tourism accommodation on offer vary according to location: as such a higher proportion of hotels are commonly found in cities, whereas a higher share of campsites, holiday homes and similar accommodation are located in coastal/rural destinations. Tourism statistics show that in 2014 just over one third (34.9 %) of the total number of bed places in hotels and similar accommodation were located in cities, while 31.3 % were in towns and suburbs, and 33.8 % in rural areas. Figure 2 shows the capacity of bed places in hotels and similar establishments relative to the resident population: in 2014, there were 31.5 bed places per 1 000 residents in rural areas of the EU-28, the corresponding ratios for towns and suburbs (26.8) and cities (23.9) were somewhat lower. However, more than half of the EU Member States reported higher ratios for cities and for towns and suburbs than they did for rural areas.

(per 1 000 residents)

Source: Eurostat (tour_cap_natd), (ilc_lvho01) and (demo_gind)

Urban areas accounted for almost two thirds of the total number of tourist nights spent in the EU-28

According to tourism statistics, there were 2.68 billion nights spent in tourist accommodation establishments across the EU-28 in 2014. The total number was relatively evenly spread by degree of urbanisation, as cities accounted for 33.8 % of nights spent, towns and suburbs for 30.0 %, and rural areas for 36.1 %. These shares may be contrasted with those already shown in Figure 1: for example, while cities provided 22.4 % of the bed place capacity in EU-28 tourist accommodation establishments, they accounted for 33.8 % of the total nights spent. This suggests that occupancy rates were higher in cities, which may be expected as cities are often visited throughout the year on short breaks, whereas some rural/coastal destinations have a considerable peak in visitor numbers during the summer months and some alpine destinations have a peak in numbers during the winter months; it is also important to note that tourism statistics include business trips, where demand is usually more evenly spread across the year.

Tourism pressures from non-residents were higher in some of the smallest EU Member States

Tourism pressures may be measured using a range of indicators, one of which is tourism intensity, defined here as the number of overnight stays in relation to the resident population — it may be used as a proxy for analysing the sustainability of tourism.

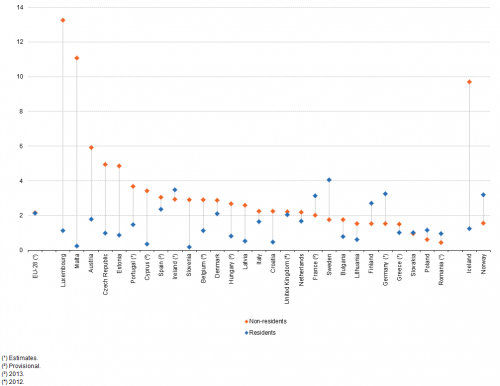

Figure 3 presents tourism intensity in tourist accommodation establishments in cities. In 2014, there was little overall difference in the EU-28 between the average number of nights spent by residents (from the same country) and non-residents (living in another country), with averages of 2.1 nights and 2.2 nights respectively. However, the size of each EU Member State clearly plays an important role in determining whether or not residents are likely to stay overnight in tourist accommodation establishments, with the average number of nights spent by residents in cities peaking in Sweden (4.1 nights spent per resident), Ireland (3.5) and (Germany (3.2). On the other hand, the average number of nights spent in cities by non-residents (again relative to the resident population) was particularly high in those Member States with relatively small populations, peaking in Luxembourg (13.3 nights per resident) and Malta (11.1).

(per resident)

Source: Eurostat (tour_occ_ninatd), (ilc_lvho01) and (demo_pjan)

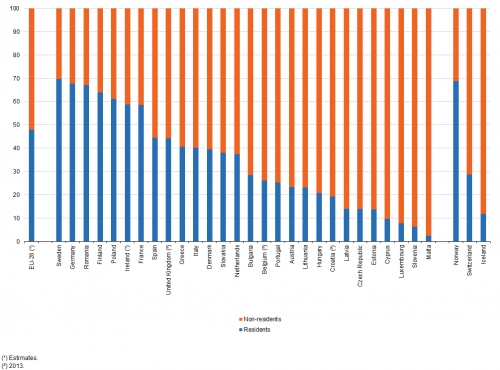

In 2014, there were a total of 367.7 million nights spent by residents in hotels and similar accommodation in cities across the EU-28, compared with 401.2 million nights spent by non-residents; as such, non-residents accounted for 52.2 % of the total nights spent (see Figure 4).

In absolute terms, the highest number of nights spent by residents in city hotels and similar accommodation was recorded in Germany, followed by France and the United Kingdom (2013 data). The share of nights spent by residents in the total number of nights spent was highest in Sweden, Germany and Romania, where it rose to just over two thirds. Finland, Poland, Ireland and France were the only other EU Member States where residents accounted for a majority of the total nights spent in city hotels and similar accommodation.

The United Kingdom, followed by Spain and Italy, recorded the highest number of nights spent by non-residents in city hotels and similar accommodation. The relative importance of non-resident nights spent was highest in the four smallest EU Member States (by total area), namely, Malta, Slovenia, Luxembourg and Cyprus, where nights spent by non-residents accounted for upwards of 90 % of the total nights spent in city hotels and similar accommodation.

(% of total)

Source: Eurostat (tour_occ_ninatd)

Some of the most intense tourism pressures were recorded in cities around the Mediterranean coastline

As noted above, the continued expansion of tourism has the potential to jeopardise environmental and social conditions. In the Mediterranean basin, tourism infrastructures and activities have sometimes resulted in irreversible and/or negative effects on areas rich in biodiversity, while there are concerns over the impact of tourism on the social fabric of some cities.

Tourism pressures

In Venezia, the number of residents living in the centro storico (old town) has fallen by more than 50 % during the last three decades to less than 60 thousand, while the number of annual visitors is over 20 million (many are day-trippers). In Barcelona, there was an exponential rise in the number of tourists after hosting the summer Olympic games in 1992, which led to rapid growth in tourist numbers and eventually prompted local residents to establish groups like Guanyem Barcelona (Let’s win back Barcelona), who coordinated protests/demonstrations and petitions against plans for building new hotels; they subsequently became part of Barcelona en Comú (Barcelona in common) and have been governing the city since May 2015, promoting a more sustainable model for tourism, while putting a one year moratorium on new hotel developments.

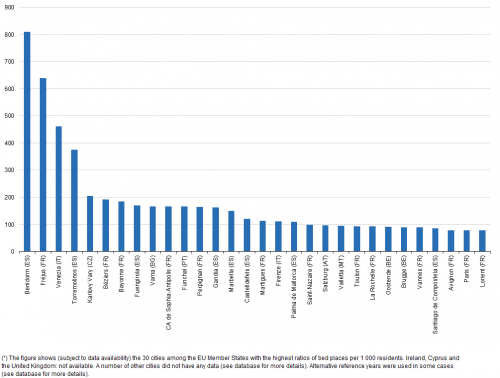

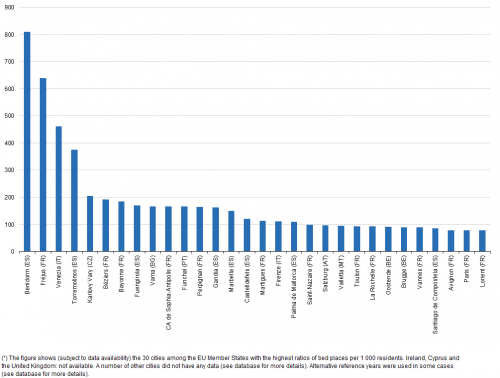

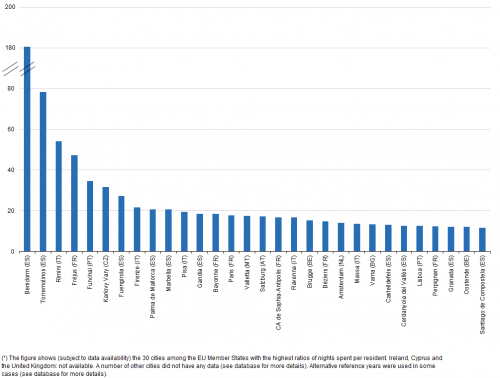

Most of the remaining data that appear in this chapter are drawn from the voluntary city statistics data collection exercise. Figure 5 shows the top 30 cities (subject to data availability) that recorded the highest ratios of bed places in tourist accommodation establishments per 1 000 residents. Among those cities for which data are available in 2013, the Spanish tourist resort of Benidorm on the Costa Blanca coastline recorded the highest ratio (810 bed places per 1 000 residents); in other words, if each of these beds was filled then the city’s population would increase by approximately 80 %. It was followed by the Mediterranean resort of Fréjus in the south of France (639 bed places per 1 000 residents; 2012 data), Venezia (461; 2008 data), the Spanish resort of Torremolinos on the Costa Del Sol (375), and the Czech spa city of Karlovy Vary (204; 2011 data).

There were 13 additional cities that reported 100–200 bed places per 1 000 residents, with five of these from each of France and Spain, and a single city from each of Bulgaria, Italy and Portugal. Aside from the Italian city of Firenze, the remaining 12 were each located within close proximity of a coastline, underlining that some of the most intense tourism pressures were in coastal resorts.

An alternative measure that may be used to analyse sustainability is tourism density — the number of overnight stays per square kilometre (km²). Tourism statistics show, as may be expected, that such pressures were highest in urban areas and particularly in capital cities, for example, Bruxelles/Brussel (Belgium), Praha (the Czech Republic), Berlin and Hamburg (Germany), Paris (France), Wien (Austria) and London (the United Kingdom).

(per 1 000 residents)

Source: Eurostat (urb_ctour)

Paris, Berlin and Roma were among the most popular city destinations in the EU

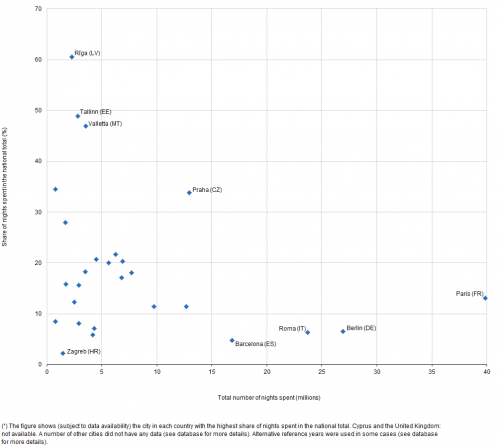

Figure 6 shows the city in each of the EU Member States with the highest share of their national total for nights spent in tourist accommodation establishments; data for Cyprus and the United Kingdom are not available. In 2013, these were principally capital cities (see Chapter 4), the only exceptions among the EU Member States being the coastal cities of Varna in Bulgaria and Barcelona in Spain (2012 data); they were joined by the Swiss city of Zürich.

Capital cities accounted for a high share of the national total for nights spent in tourist accommodation establishments in the Baltic Member States, Malta, Luxembourg and the Czech Republic. This was particularly the case in Rīga, which accounted for more than half (60.5 %) of all the nights spent in Latvia, while shares just under 50 % were recorded for Tallinn (Estonia) and Valletta (Malta; 2008 data).

In absolute terms, the highest number of nights spent in tourist accommodation establishments was recorded in the French capital of Paris, some 39.9 million (2012 data). This was considerably higher than in the German capital of Berlin (26.9 million; 2013 data) or the Italian capital of Roma (23.7 million; 2011 data); note again that there is no data available for London.

Paris accounted for 13.1% of the nights spent in French tourist accommodation establishments in 2012. Capital cities in the other most populous EU Member States generally recorded lower shares: this pattern was particularly evident in Berlin, Roma (2011 data), and Madrid (Spain; 2012 data) — none of which accounted for more than 6.5 % of the total nights spent on their national territories; a lower share (2.2 %) was recorded in the Croatian capital of Zagreb, with the vast majority of nights spent in Croatia being on the Adriatic coastline.

Source: Eurostat (urb_ctour)

Figure 7 shows the average number of nights spent in tourist accommodation establishments; once again data are not available for Cyprus and the United Kingdom. This indicator may be used as a measure of tourism pressures: for example, for each inhabitant in Benidorm (Spain), an average of 181 nights was spent in tourist accommodation establishments during the course of 2013. This was the highest ratio among EU cities for which data are available, while relatively high ratios were also recorded in a number of other coastal resorts including Torremolinos (Spain; 78 nights) and Fréjus (France; 47 nights in 2012), as well as the Italian resort of Rimini on the Adriatic coastline (54 nights; 2011 data) and the capital of the autonomous Portuguese island of Madeira, Funchal (35 nights; 2012 data); note that many of the tourist accommodation establishments in these holiday resorts are characterised by fluctuating seasonal occupancy levels, and that associated tourism pressures are likely to be considerably greater during the high season than these annual averages might suggest.

Aside from these coastal resorts, the top 30 cities with the highest average number of nights spent was also characterised by capital cities and by historical/cultural cities. For example, using this measure, tourism pressures appeared to be relatively high in the capital cities of Paris, Valletta (Malta), Amsterdam (the Netherlands) and Lisboa (Portugal), as well as in the historical/cultural cities of Firenze and Pisa (both Italy), Granada and Santiago de Compostela (both Spain), Salzburg (Austria) and Brugge (Belgium).

(per resident)

Source: Eurostat (urb_ctour) and (urb_cpop1)

Culture and heritage

As noted above, Europe has a considerable cultural heritage, whether modern or contemporary, focused on design, fashion, architecture, cuisine, performing and visual arts, sports, or other areas.

European capital of culture

The organisation of the European capital of culture is one of the most high-profile cultural initiatives in Europe. The cities are chosen on the basis of a cultural programme that must have a strong European dimension, engage and involve the city’s inhabitants, and contribute to the long-term development of the city. Events such as these have stimulated large tourist flows to some of the cultural capitals and have seen their branding and profile rise.

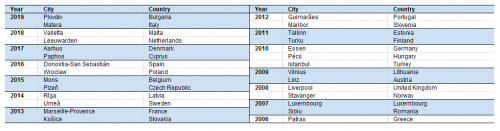

Table 1 presents the European capital(s) of culture during the period 2006–19. In 2016, the 31st edition of the European capital of culture is shared between Wrocław in Poland, and Donostia/San Sebastián in Spain. The former has organised almost 100 cultural events, behind the motto ‘Spaces of beauty’, while the programme for the latter is built on the idea of ‘Culture to live together’, exploring how art and culture help people and communities live together.

Future European capitals of culture will include Aarhus (Denmark) and Paphos (Cyprus) in 2017, Valletta (Malta) and Leeuwarden (the Netherlands) in 2018, and Plovdiv (Bulgaria) and Matera (Italy) in 2019.

Source: European Commission, Directorate-General for Education and Culture (http://ec.europa.eu/programmes/creative-europe/actions/capitals-culture_en.htm)

Although cultural tourism in cities continues to be dominated by the established ‘cultural capitals’ — for example, Athina in Greece, Paris in France, or Roma in Italy — there are a range of alternative destinations which are experiencing a growing number of visitors, for example, Antwerpen (Belgium), Valencia (Spain) or Glasgow (the United Kingdom). Indeed, there appears to be a shift away from purely heritage-based tourism towards those cities that offer additional forms of culture/creativity; in some cities these are exhibited through festivals and other special events.

World Heritage Sites in Europe

Cultural and natural heritage are irreplaceable sources of life and inspiration: the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) list of World Heritage Sites covers a diverse range of places. To be included on the list, sites must be of outstanding universal value; they may include cultural traditions, buildings, monuments, architecture, landscapes, natural habitats, geological or biological processes or natural phenomenon.

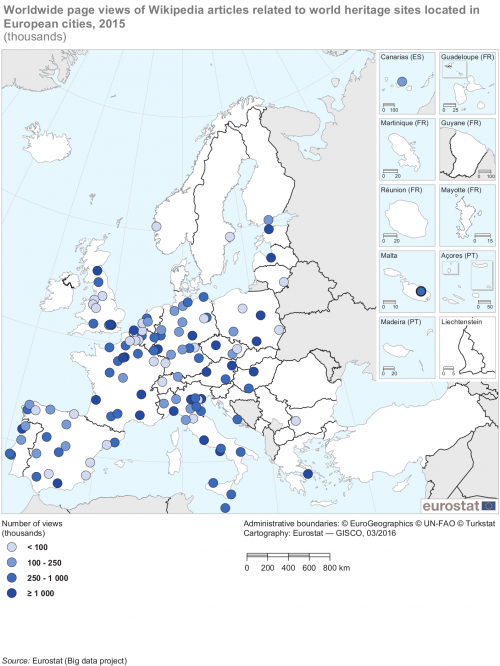

Map 1 presents the number of worldwide page views of Wikipedia articles related to World Heritage Sites that are located in European cities. The statistics presented should be considered as experimental insofar as they are based on publically available data released by the Wikimedia Foundation. Wikipedia articles were linked to World Heritage Sites in European cities based on a Wikipedia categorisation; the number of page views per month was computed based on access to a set of articles in 31 different languages (all 24 official and working languages of the EU, as well as Albanian, Icelandic, Macedonian, Norwegian, Russian, Serbian and Turkish); the data excludes access to Wikipedia from mobile devices.

Although the list is not exhaustive, the highest number of page views was in relation to the French capital of Paris (6.8 million views), followed by the Italian capital of Roma. The number of page views for the Austrian and Hungarian capitals of Wien and Budapest were approximately half the level recorded for Paris, while there were also more than 3 million page views in relation to the Czech capital of Praha and the Italian city of Venezia.

There were 27 World Heritage Sites in the EU which received more than a million page views of their Wikipedia articles, they were spread across the continent, with: five in each of France and Italy; three in the United Kingdom; two in each of Germany, Austria and Poland; and a single site in each of Belgium, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Greece, Spain, Latvia, Hungary and Portugal.

Cinema attendance was relatively high in relatively small, provincial cities …

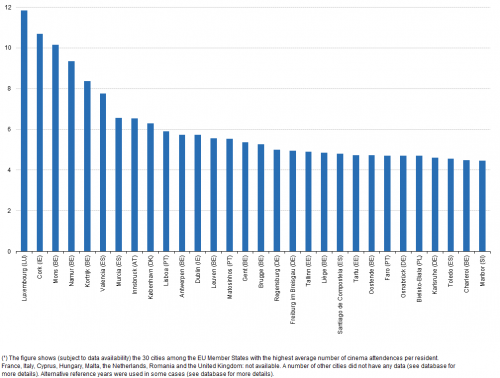

Many cities in the EU have a vibrant cultural and arts scene. Figures and 9 provide information on the number of cinema visits and museum entries for selected cities; note that these statistics may include visits/trips made by residents as well as by non-residents (tourists).

Subject to data availability, there were three cities in the EU where the average number of cinema visits per resident rose above 10.0 in 2012, they were: Luxembourg (11.8 trips; 2009 data), Cork in Ireland (10.7 trips) and Mons in Belgium (10.2 trips). The relatively high average number of cinema visits per resident in Luxembourg may, at least in part, reflect the large number of people who commute to work each day from neighbouring countries (some of whom may stay in the evening to watch a film before returning home). Some of the highest attendance rates were recorded in relatively small, provincial cities, rather than bigger capitals and metropolises where a range of alternative cultural experiences may be offered.

(per resident)

Source: Eurostat (urb_ctour) and (urb_cpop1)

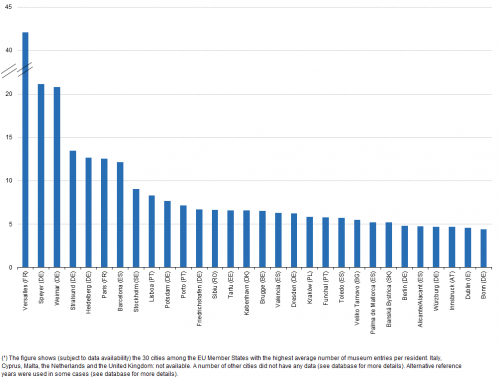

Subject to data availability (see Figure 9 for more details), Versailles in France had the highest number of museum entries per resident (42.1 in 2013). The top 30 cities with the highest average number of museum entries per resident was also characterised by a number of relatively small cities, particularly those from Germany and Spain. For example, the German cities included: Speyer, just to the west of Heidelberg; Stralsund on the holiday island of Rugen in the Baltic Sea; Friedrichshafen on the shores of Lake Constance in southern Germany; or Würzburg in central Germany. The ranking also included Sibiu in Transylvania (Romania; 2012 data), which was a former European capital of culture in 2007, and Toledo (Spain; 2008 data) which is a World Heritage Site to the south of Madrid.

… while some of Europe’s largest capitals recorded high numbers of museum entries

There were also a number of established ‘cultural capitals’, including Paris, Barcelona, Stockholm (Sweden), Lisboa, København (Denmark), Brugge (Belgium), Dresden (Germany), Berlin, Kraków (Poland) and Dublin (Ireland) where high numbers of museum entries were recorded. In absolute terms and subject to data availability (note there are no data presented for, among others, Italy and the United Kingdom), Paris (28.1 million museum entries in 2013), Barcelona (19.6 million in 2011) and Berlin (16.1 million in 2013) were considerably ahead of the other cities, as the next highest numbers of museum entries were recorded in Stockholm (7.8 million; 2011 data) and Versailles (7.6 million entries; 2013 data).

(per resident)

Source: Eurostat (urb_ctour) and (urb_cpop1)

Source data for tables and graphs

Direct access to

- Urban Europe — statistics on cities, towns and suburbs (online publication)

- Culture (articles on culture)

- Degree of urbanisation classification - 2011 revision

- Eurostat regional yearbook

- Statistics on regional typologies in the EU

- Regions and cities (all articles on regions and cities)

- Territorial typologies

- Territorial typologies for European cities and metropolitan regions

- Tourism (all articles on tourism)

- What is a city?

- Capacity and occupancy of tourist accommodation (ESMS metadata file — tour_occ_esms)

- Urban audit (ESMS metadata file — urb_esms)

- Regional statistics by typology (ESMS metadata file — reg_typ_esms)

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy, Urban development

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy, A harmonised definition of cities and rural areas: the new degree of urbanisation

- OECD, Redefining urban — a new way to measure metropolitan areas