Archive:Urban Europe — statistics on cities, towns and suburbs — foreign-born persons living in cities

Data extracted in February–April 2016.

This Statistics Explained article has been archived on 4 December 2020.

Highlights

Greater London was the most cosmopolitan capital city in the EU in 2011 with almost three million of its inhabitants born outside the United Kingdom.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (urb_percep) and (urb_cpop1)

This chapter is part of an online publication that is based on Eurostat’s flagship publication Urban Europe — statistics on cities, towns and suburbs (which also exists as a PDF).

Definitions of territorial units

The various territorial units that are presented within Urban Europe — statistics on cities, towns and suburbs are described in more detail within the introduction. Readers are encouraged to read this carefully in order to help their understanding and interpretation of the data presented in the remainder of the publication.

Full article

Foreign-born persons living in cities

Migration is both an opportunity and a challenge for the European Union (EU). Migrants have historically played an important role in demographic and economic developments, particularly in some of Europe’s largest cities. The selective nature of migratory patterns is such that migrant destinations are often restricted to relatively few, large cities, which tend to receive a disproportionate number of immigrants. These patterns are often accentuated as first wave migrants who establish themselves in a particular part of a city may subsequently encourage relatives and friends to follow them.

The percentage of foreigners living in many of Europe’s cities has risen and increased mobility and some declining national or regional populations will likely result in more migrants arriving in urban areas of the EU during the coming decades. These developments are likely to be particularly prevalent in the largest global economic centres which often act as magnets for migrants.

The EU’s external borders have witnessed a range of human tragedies in recent years as unprecedented flows of hundreds of thousands of asylum seekers and migrants have crossed the Mediterranean to Italy or Greece. While national statistics already capture many of these developments, data on cities and metropolitan regions generally take several years to produce and so do not yet reflect these extraordinary events.

European policy responses to asylum seekers and migrants

Migration was identified as a key priority at the start of the Juncker Commission and its importance has grown each year, with unfolding events in many parts of the world, in particular North Africa, the Horn of Africa, the Middle East, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Ukraine. The European agenda on migration (COM(2015) 0240 final) outlines both short-term measures to prevent human tragedies and strengthen emergency responses, as well as longer-term initiatives that are designed to help manage migration flows. The agenda seeks, among others, to: save lives and secure external borders; provide policy initiatives relating to legal migration; reduce the incentives for irregular migration.

Asylum should be granted to people fleeing persecution or serious harm in their own country; it is recognised as a right within the EU’s charter of fundamental rights (Article 18). EU Member States should share responsibility to welcome asylum seekers, ensuring they are treated fairly and that their case is examined to uniform standards. On 6 April 2016, the European Commission adopted a Communication, Towards a reform of the common European asylum system and enhancing legal avenues to Europe (COM(2016) 197 final), launching a new reform initiative for: a fairer and more sustainable asylum system — the Common European Asylum System (CEAS); further harmonisation of asylum procedures and standards; strengthening the mandate of the European Asylum Support Office (EASO).

At the same time, the Commission set out measures to ensure safe and well-managed pathways for legal migration to Europe, both for those seeking protection and for those seeking work. A range of initiatives are proposed to try to achieve these goals, including: providing financial assistance to countries in northern African so they can improve their search and rescue activities; investigating, disrupting and prosecuting smuggler networks; ensuring that Europe remains an attractive destination for migrants in view of the future demographic challenges, for example, by facilitating entry and the recognition of qualifications.

There are two drivers of population change: on the one hand, natural population change (the difference between the number of births and the number of deaths) and, on the other, net migration (the difference between the number of people who move into and out of a geographic territory). As natural population growth within the EU has generally stagnated and turned to decline in some cases, the relative impact of migration on overall population change has become greater.

At the start of 2015, there were 52.8 million people living in the EU-28 who had been born in a foreign country; this equated to almost 10 % of the total population, with a majority of those born in a foreign country coming from outside the EU. During the period 2009–14, the crude rate of natural population change in the EU-28 was 0.6 per 1 000 inhabitants, while the crude rate of net migration was more than four times as high at 2.6 per 1 000 inhabitants. The three EU Member States with the highest crude rates of natural population change over the period 2009–14 were Ireland, Cyprus and France, while the three EU Member States with the highest crude rates of net migration were Luxembourg, Sweden and Italy.

Migration in metropolitan regions

This section is based on migratory flows into and out of metropolitan regions: it is important to note that while much debate surrounds patterns of international migration, the vast majority of population movements that take place within the EU generally do so within the confines of national borders. Indeed, some EU Member States have seen considerable geographical shifts in their populations, for example, from eastern to western Germany, from southern to northern Italy, or from the north to the south-east of the United Kingdom.

The metropolitan region of Luxembourg recorded the highest rate of population growth during the period 2009–14

Figure 1 shows the 15 metropolitan regions in the EU, Norway and Switzerland with the lowest/highest overall rates of population change during the five-year period from 2009–14, analysed in terms of natural population change and net migration. Note that the end of this period (2014) only captures the start of the recent surge in asylum-seekers/migrants arriving in the EU.

An analysis across all of the metropolitan regions in the EU shows that the Irish capital of Dublin recorded the highest crude rate of natural population change during the period 2009–14 (11.3 per 1 000 inhabitants). The second highest rate was recorded in the French capital region (Paris; 9.3 per 1 000 inhabitants), while two further regions from Ireland and France — Cork and Lyon — recorded the third and fourth highest rates; they were followed by four regions from the United Kingdom, namely, Bradford, London, Reading and Southampton. By contrast, crude rates of natural population change during the period 2009–14 were below -5.0 per 1 000 inhabitants, indicating a considerably higher number of deaths than births, in the German metropolitan regions of Bremerhaven, Hildesheim, Lübeck and Saarbrücken, the Spanish region of Oviedo – Gijón, the Italian region of Genova (a popular retirement destination) and the south-western Romanian region of Craiova.

In relative terms, the fastest expanding metropolitan region in the EU was Luxembourg, where the crude rate of population change was 22.0 per 1 000 inhabitants. Although Luxembourg had a relatively high crude rate of natural population change (4.0 per 1 000 inhabitants), its crude rate of net migration was 4.5 times as high (18.0 per 1 000 inhabitants). A closer analysis of migrant flows into Luxembourg reveals that a majority of these were people who had been born in other EU Member States, principally in Portugal, France, Luxembourg (returning to their home country), Belgium, Italy and Germany. The next highest crude rate of population change among the regions shown in Figure 1 was in Oslo (Norway), followed by two more metropolitan regions covering capital cities, namely, Roma (Italy) and Stockholm (Sweden). The remaining metropolitan regions from the EU with the highest crude rates of population change included four French regions (Montpellier, Toulouse, Bordeaux and Nantes), two regions from the United Kingdom (London and Southampton) and the Bavarian region of München (Germany).

Net migration was generally the main driver of change among the 15 metropolitan regions with the highest rates of overall population change. However, a different pattern was observed for London and Southampton, as these were the only metropolitan regions (among the top 15) where the crude rate of natural population change (7.5 and 6.7 per 1 000 inhabitants) exceeded the crude rate of net migration (4.6 and 4.8 per 1 000 inhabitants).

It is interesting to note the relatively fast pace of population growth in a number of metropolitan regions outside the EU-28, as the Norwegian regions of Oslo and Bergen as well as the Swiss regions of Lausanne, Zürich and Genève all featured among the top 15 regions with the highest overall rates of population change; in keeping with the pattern generally observed for the EU regions, each of these recorded higher crude rates of net migration than crude rates of natural population change.

During the period 2009–14, the fastest outward flows of migrants tended to be recorded in some of the metropolitan regions most affected by the financial and economic crisis, for example, two regions from the Baltic Member States (Kaunas and Rīga), two regions from Greece (Thessaloniki and Athina), two regions from Ireland (Cork and Dublin), three regions from Spain (Barcelona, Madrid and Valencia), and a single region from Portugal (Coimbra).

(per 1 000 inhabitants)

Source: Eurostat (met_gind3)

The metropolitan regions of capitals often recorded some of the highest inflows of migrants

Figure 2 analyses changes in net migration for metropolitan regions in terms of absolute numbers rather than crude rates of change. During the period 2009–14, two patterns were apparent regarding inflows: a relatively high number of migrants arrived in several of the metropolitan regions covering EU capital cities, while there were high numbers of migrant inflows across a range of large German metropolitan regions.

The highest level of net migration during the period 2009–14 was recorded in the Italian capital city region (Roma), where net migration averaged 70.7 thousand per annum; this was somewhat higher than in London (62.3 thousand). The next highest level of net migration was recorded in another Italian metropolitan region, namely, that of Milano (42.8 thousand), which was followed by two German metropolitan regions, the capital city region (Berlin, 38.3 thousand) and München (26.3 thousand); Hamburg (20.6 thousand) and Frankfurt am Main (19.6 thousand) were also present among the 15 regions with the highest average levels of net migration. The remaining metropolitan regions with high levels of net migration were all capital city regions: Wien (Austria), Budapest (Hungary), Stockholm (Sweden), Bruxelles/Brussel (Belgium), Warszawa (Poland), Praha (the Czech Republic), København (Denmark) and Oslo (Norway).

The largest outflows of migrants (in absolute terms) were recorded among those leaving the metropolitan regions of the French and Greek capitals: Paris (an average of 53.2 thousand each year during the period 2009–14) and Athina (an average of 29.6 thousand; 2009–13). They were followed by the two largest Spanish metropolitan regions of Madrid and Barcelona, where there were on average 18.7 thousand and 18.4 thousand net departures per year. The ranking of metropolitan regions with the largest outflows of migrants contained a number of other regions from southern Europe, with an additional region from each of Spain (Valencia) and Greece (Thessaloniki; 2009–13), and one from Portugal (Porto (2009–13). Aside from these, the other metropolitan regions with the largest outflows of migrants included the Irish regions of Dublin and Cork, the Baltic regions of Kaunas and Rīga, and a few regions characterised by their relatively high specialisation in (heavy) industrial activities: the French regions of Lille - Dunkerque - Valenciennes and Rouen; the Polish region of Katowice; and the Hungarian region of Miskolc.

(number)

Source: Eurostat (met_gind3)

Foreign-born populations in predominantly urban and metropolitan regions

With the exception of Luxembourg (45.3 %), foreign-born populations accounted for less than 20 % of the total number of inhabitants in each of the EU Member States in 2014. Several of the smaller Member States — Cyprus, Latvia, Estonia and Ireland — as well as Austria and Spain, reported that foreign-born persons accounted for between 10 % and 20 % of their total populations, while at the other end of the range foreign-born persons accounted for less than 1 % of the total number of inhabitants in Bulgaria, Croatia, Lithuania, Romania and Poland.

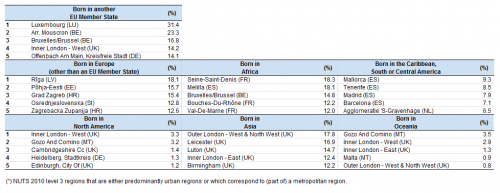

Table 1 provides information based on NUTS level 3 regions that are either predominantly urban or which correspond to (part of) a metropolitan region; the statistics shown relate to those regions with the highest shares of foreign-born inhabitants, analysed by continent of birth. While some regions attract the majority of their migrants from a narrow range of countries — others are extremely diverse, drawing migrants from around the world. This is particularly true for some of Europe’s largest cities and capital cities, for example, the regions of Hamburg, München, Paris, Amsterdam, Stockholm or London.

Almost one third of the population in Luxembourg was born in another EU Member State

In 2011, Luxembourg (a single region at this level of detail) had almost one third (31.4 %) of its inhabitants born in another EU Member State, which was considerably higher than in any other region. The Belgian region of the Arrondissement de Mouscron (which is situated next to the French border) had the second highest share (23.3 %) of its population born in another EU Member State, while those born in other EU Member States accounted for between one sixth and one seventh of the total populations of Bruxelles/Brussel, Inner London - West, and the German region of Offenbach am Main (located to the south-east of Frankfurt am Main).

Geographic proximity, ex-colonial links, common languages and cultural ties play an important role in determining the destinations that are favoured by migrants

Table 1 also provides an analysis of the origin of foreign-born populations for 2011 for other parts of the world. The share of foreigners born in other European countries peaked in the capital city regions of Latvia and Estonia, and was largely composed of people that had been born in Russia, while the foreign-born populations of Grad Zagreb and Zagrebacka Zupanija (the Croatian capital city region and its surrounding region) and the central Slovenian region of Osrednjeslovensk (which includes Ljubljana, the Slovenian capital) were largely composed of people who had been born in other parts of former Yugoslavia.

In 2011, those regions with the highest shares of foreign-born inhabitants from Africa included three French regions (Seine-Saint-Denis, the Bouches-Du-Rhône and the Val-De-Marne), the Belgian capital city region of Bruxelles/Brussel, and the autonomous Spanish city of Melilla (which is on the African continent). The four regions in the EU with the highest shares of people born in Central/South America and the Caribbean were all Spanish, namely, Mallorca, Tenerife, Madrid and Barcelona. A high share of the foreign-born migrants from Asia chose to reside in the United Kingdom, as the five regions with the highest shares of foreigners born in Asia included two regions from London (Outer London - West & North West and Inner London - East), as well as Leicester, Luton and Birmingham.

>

(% share of total population)

Source: European Statistical System, the Census Hub https://ec.europa.eu/CensusHub2

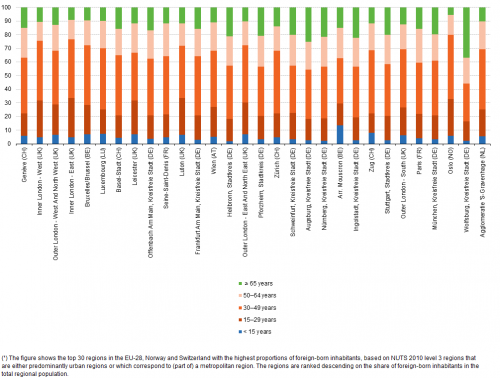

Foreign-born populations living in urban regions are typically of working age

Figure 3 shows the share of five different age groups in the total number of foreign-born inhabitants living in selected urban regions. It presents information for the 30 NUTS level 3 regions with the highest proportions of foreign-born inhabitants (again based on a selection of regions that are either predominantly urban or which correspond to (part of) a metropolitan region).

All but one of the 30 predominantly urban/metropolitan regions shown in Figure 3 recorded their highest share of foreign-born inhabitants among those aged 30–49 years. Three of these reported that their share of 30–49 year-olds in the total number of foreign-born inhabitants rose above 45.0 %; all three were located outside the EU, with two from Switzerland (Zug and Zürich) and the third being the Norwegian capital city region of Oslo. Within the EU Member States, the share of foreign-born inhabitants who were aged 30–49 peaked in Luxembourg (44.9 %; one region at this level of analysis) and the Dutch region of the Agglomeratie 'S-Gravenhage (44.0 %).

The only exception to this pattern, where those aged 30–49 did not account for the highest share of foreign-born inhabitants, was the German region of Wolfsburg, Kreisfreie Stadt, where the highest share of foreign-born inhabitants was recorded among those aged 65 years and more — many of the elderly foreign-born persons living in this region are likely to have been Gastarbeiter (guest workers) from Italy and Turkey who had up until their retirement been employed within the car manufacturing industry.

(% of foreign-born inhabitants)

Source: European Statistical System, the Census Hub https://ec.europa.eu/CensusHub2

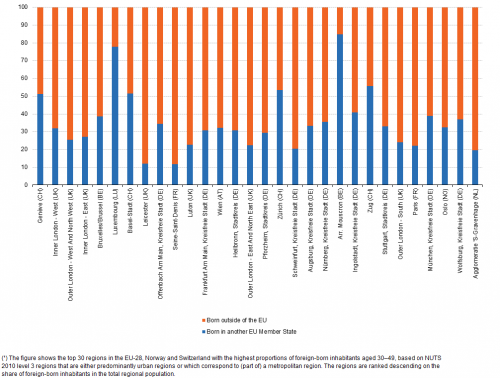

More than three quarters of the foreign-born inhabitants aged 30–49 living in Luxembourg and the Belgian region of Mouscron were born in another EU Member State …

Figure 4 is also based on the 30 predominantly urban/metropolitan regions which had the highest shares of foreign-born inhabitants in 2011; it provides an analysis of the relative share of foreign-born residents aged 30–49 according to whether they were born in another EU Member State or outside the EU. The ranking is dominated by those born outside the EU, as these were in the majority for 24 of the 30 regions shown. The only exceptions, with a higher share of their foreign-born populations originating from other EU Member States were four Swiss regions (Genève, Basel-Stadt, Zürich and Zug), Luxembourg (a single region at this level of detail) and the Belgian region of the Arrondissement de Mouscron. In these latter two regions, some 77.8 % and 84.7 % of the foreign-born inhabitants aged 30–49 had been born in another EU Member State.

… while almost 9 out of every 10 foreign-born inhabitants aged 30–49 living in the French region of Seine-Saint-Denis and the United Kingdom region of Leicester were born outside the EU

In 2011, there were eight regions among the 30 with the highest shares of foreign-born inhabitants where more than three quarters of the foreign population aged 30–49 had been born outside the EU. Four of these were located in the United Kingdom (Outer London - South, Outer London - East and North East, Luton and Leicester), two were located in France (including Seine-Saint-Denis and the capital city region of Paris), while the other two were Schweinfurt, Kreisfreie Stadt in Germany (which used to have a United States’ military base in 2011) and the Agglomeratie ‘S-Gravenhage (the Hague) in the Netherlands.

(% of foreign-born inhabitants aged 30–49)

Source: European Statistical System, the Census Hub https://ec.europa.eu/CensusHub2

Foreign-born populations in cities

Greater London had the highest number of foreign-born inhabitants among cities in the EU — almost three million

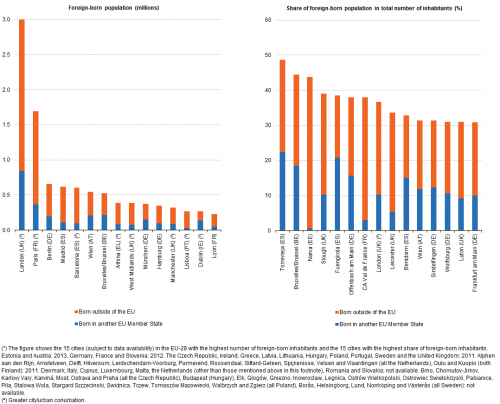

Figure 5 shows the 15 cities in the EU-28 with the highest number of foreign-born inhabitants. By this measure, Greater London was the most cosmopolitan capital city in the EU: with almost three million of its inhabitants born outside the United Kingdom (2011 data). The four largest communities of foreign-born inhabitants in the EU were all located in capital cities, namely, Greater London, Greater Paris (1.7 million; 2012 data), Berlin (652 thousand; 2012 data) and Madrid (619 thousand; 2014 data), while the top 15 cities in terms of their absolute number of foreign-born residents also included the capitals of Austria (2013 data), Belgium (2014 data), Greece (Greater Athina; 2011 data), Portugal (Greater Lisboa; 2011 data) and Ireland (Greater Dublin; 2011 data).

The Irish capital of Greater Dublin was the only city (among those shown in the first half of Figure 5) to record a higher share of its foreign-born inhabitants originating from another EU Member State (52.2 % of those born abroad) rather than from outside the EU. In Greater London, almost three quarters (72.0 %) of the foreign-born inhabitants were from countries outside the EU, while shares of more than three quarters (among the selected cities shown in the first half of Figure 3) were recorded for the French cities of Lyon and Greater Paris (both 2012 data), Greater Athina, the West Midlands conurbation in the United Kingdom (2011 data), as well as the three Iberian cities of Madrid, Greater Barcelona (both 2014 data) and Greater Lisboa (2011 data); the highest share of foreign-born inhabitants originating from countries outside the EU was recorded in the latter, at 88.2 %.

A majority of the foreign-born populations living in EU cities were born outside of the EU

The second half of Figure 5 presents information on those cities where foreign-born inhabitants accounted for the highest share of the total number of inhabitants in 2014. The list is composed of a number of relatively small cities, although it also features three capitals: Bruxelles/Brussel, Greater London (2011 data) and Wien (2013 data). The city with the highest share of foreign-born inhabitants was Torrevieja (which is close to Alicante in south-east Spain), where almost half (48.7 %) of the population was born abroad, while the second highest share was recorded in Bruxelles/Brussel (44.4 %); in both cases, a majority of the foreign-born population originated from outside the EU. Narva is Estonia’s third largest city and is located in the north-east of the country: in 2013, almost all of its foreign-born inhabitants had been born outside the EU, principally in Russia (onto which Narva borders). Foreign-born inhabitants from outside the EU also accounted for a high share of the total foreign-born population in the Communauté d’agglomération Val de France (located in the northern suburbs of Paris; 2012 data), as well as Leicester and Luton in the United Kingdom (both 2011 data). Indeed, among the 15 cities shown in the second half of Figure 5, the Spanish holiday destination/retirement city of Fuengirola on the Costa del Sol was the only city where a majority of the foreign-born populated originated from another EU Member State (53.9 % of all foreign-born inhabitants in 2014).

Source: Eurostat (urb_cpopcb)

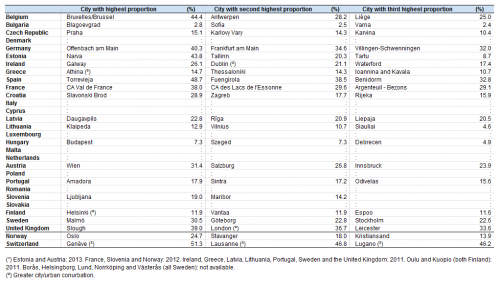

Capital cities often recorded some of the highest shares of foreign-born inhabitants

Foreign-born inhabitants accounted for a relatively high share of the total population in many of the larger cities in western and northern Europe (including Norway and Switzerland). The lowest shares of foreign-born residents were often recorded in the eastern EU Member States, where foreign-born nationals often accounted for less than 2 % of the total population, except in the capital cities and a few other larger cities.

The share of foreign-born inhabitants in the total population of larger cities tended to be greater than the national average. For example, among the 19 EU Member States for which data are available (see Table 2), seven reported that their capital city had the highest share of foreign-born inhabitants in the total population, while the capital cities of seven other Member States recorded the second highest share, and Stockholm (Sweden; 2011 data) the third highest share. This left just four of the 19 Member States for which data are available where the capital city did not feature among the top three cities with the highest proportions of foreign-born residents, namely, Germany, Spain, France (2012 data) and Portugal (2011 data).

Source: Eurostat (urb_cpopcb)

Foreign-born populations in subcity districts

Figure 6 presents information at the subcity level for Berlin and London, detailing the share of foreign-born inhabitants from other EU Member States and from outside the EU. In 2011, the total share of foreign-born inhabitants peaked in Berlin at 43.2 % in the central district of Mitte, with more than three times as many foreign-born inhabitants from outside the EU compared with those born in another EU Member States (33.0 % of the total population compared with 10.1 %). The share of foreign-born inhabitants was consistently higher for those born outside the EU in all of the Berlin districts, although in the northern district of Pankow and the south-western district of Treptow-Köpenick there was a relatively small difference between the respective shares (note however that both of these districts had relatively low shares of foreign-born inhabitants).

There was an even wider range in the share of foreign-born inhabitants across London boroughs in 2011. At one end of the spectrum, foreign-born inhabitants made up 10.3 % of the total population in the east London borough of Havering (where 3.4 % of the total population were born in another EU Member State and 6.9 % were born outside the EU). By contrast, there were four London boroughs where the foreign-born population accounted for more than half the total number of inhabitants — the relatively working-class boroughs of Brent (north-west London) and Newham (east London), and the affluent boroughs of Westminster (central London) and Kensington and Chelsea (west London). The share of inhabitants born in another EU Member State peaked among London boroughs in Kensington and Chelsea (18.5 %), while the share of those born outside the EU rose to over 40.0 % in Newham and Brent.

(% of total population)

Source: Ergebnisse des Zensus 2011,

Statistical Office for Berlin-Brandenburg

https://www.statistik-berlin-brandenburg.de/home.asp

and Eurostat (urb_cpopcb)

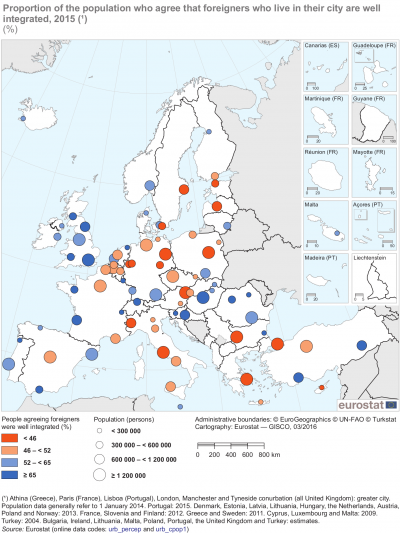

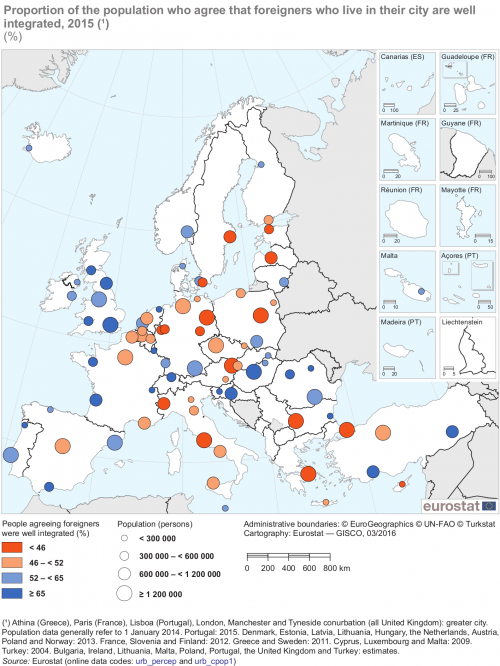

Self-perceived impact of migrant communities

Discussions relating to social cohesion are often focused on the impact of migrant communities with different cultural, linguistic and social backgrounds and the challenges that migrants face in adapting to their new home. Map 1 presents information from a perception survey on the quality of life in 79 European cities conducted in 2015 across 79 European cities; note that the statistics presented for Athina (Greece), Paris (France), Lisboa (Portugal), London, Manchester and the Tyneside conurbation (all in the United Kingdom) relate to the concept of the greater city. The map shows the proportion of city-dwellers who agreed that foreigners living in their city were well integrated. Given the extraordinary number of asylum seekers and migrants who moved through Europe during the summer of 2015, it is possible that the views expressed in May–June 2015 have subsequently shifted.

The share of respondents in capital cities agreeing that foreigners were well integrated was often below the proportions recorded in other cities for which data are available; this was particularly the case in Sofia (31 % of the population agreed that foreigners were well integrated), Roma (30 %) and Greater Athina (20 %). On the other hand, there were some capital cities where a clear majority of the population agreed that foreigners were well integrated into city life, for example, Greater Lisboa (64 %), Greater London (65 %), Budapest (66 %), Luxembourg (67 %) and Zagreb (77 %); note that in cities such as London or Luxembourg, a high proportion of respondents could themselves have been foreign-born.

Outside of capital cities, some of the highest levels of agreement concerning the good integration of foreigners were recorded in cities characterised by relatively large foreign populations, for example, the Spanish city of Málaga or the Swiss cities of Genève and Zürich. Some of the lowest levels of agreement concerning the integration of foreigners were recorded in cities with relatively low numbers of foreign-born inhabitants, for example, some cities in eastern Germany or Poland.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (urb_percep) and (urb_cpop1)

Diversity is increasingly becoming a defining element of many European cities …

Concerns over the contribution of migrants in EU cities do not necessarily increase as the share of foreigners in the total number of inhabitants rises; on the contrary, some of Europe’s most cosmopolitan cities, for example, København, Amsterdam and London display a diversity and fusion of cultures, ideas, arts and fashion.

As part of the perception survey on the quality of life, respondents were asked whether or not they agreed that the presence of foreigners was good for their city. In 2015, the highest proportions of city-dwellers agreeing that foreigners were good for their city were recorded in Cluj-Napoca (north-western Romania), København (Denmark), Dublin (Ireland), Zagreb (Croatia), Luxembourg (Luxembourg), Reykjavik (Iceland) and Zürich (Switzerland); note that five of these seven cities were capital cities.

… although a minority of the population in six cities agreed that the presence of foreigners was good for their city

At the other end of the range, the lowest levels of agreement with the premise that foreigners were good for their city — less than 50 % — were recorded in four southern cities from the EU — the Greek capital of Greater Athina and the three Italian cities of Bologna, Roma and Torino — as well as two Turkish cities, namely, Ankara and Istanbul.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (urb_percep) and (urb_cpop1)

Source data for tables and graphs

Direct access to

- Urban Europe — statistics on cities, towns and suburbs (online publication)

- Degree of urbanisation classification - 2011 revision

- Eurostat regional yearbook

- Migrant integration statistics (online publication)

- Statistics on regional typologies in the EU

- Regions and cities (all articles on regions and cities)

- Territorial typologies

- Territorial typologies for European cities and metropolitan regions

- What is a city?

- Perception survey on quality of life in 79 European cities

- Urban audit (ESMS metadata file — urb_esms)

- Regional statistics by typology (ESMS metadata file — reg_typ_esms)

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy, Urban development

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy, A harmonised definition of cities and rural areas: the new degree of urbanisation

- OECD, Redefining urban — a new way to measure metropolitan areas