Archive:Quality of life in Europe - facts and views - overall life satisfaction

This article has been archived. The paper format and the PDF format latest edition, ISBN 978-92-79-43616-1, doi:10.2785/59737, Cat. No KS-05-14-073-EN-N are still available. For updated information on quality of life, see the online publication Quality of life indicators.

<thumb src="Dashboard Overall life satisfaction.png">

Dashboard 1: Overall life satisfaction

© EuroGeographics for the administrative boundaries

Click on the image for an interactive view of the data

Source: Eurostat (ilc_pw05)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_pw01) and (ilc_pw05)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_pw01) and (ilc_pw05)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_pw01) and (ilc_pw05)

Source: Eurostat (EU SILC)

Source: Eurostat (EU SILC)

Source: Eurostat (EU SILC)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_pw01) and (ilc_pw05)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_pw01) and (nama_10_pc)

Source: Eurostat (EU SILC)

Source: Eurostat (EU SILC)

Source: Eurostat (EU SILC)

Source: Eurostat (EU SILC)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_pw05)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_pw01) and (ilc_pw05)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_pw01) and (ilc_pw05)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_pw01) and (ilc_pw05)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_pw01)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_pw08)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_pw08)

Source: Eurostat (EU SILC)

Source: Eurostat (EU SILC)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_pw05) and (ilc_pw08)

Source: Eurostat (EU SILC)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_pw05) and (ilc_pw08)

This article focuses on well-being of people in the European Union (EU) and is part of a set of articles forming the publication Quality of life in Europe - facts and views. Subjective well-being allows an integration of the diversity of the experiences, choices, priorities and values of an individual. The data used on subjective evaluations and perceptions of different domains were collected for the first time in European official statistics through the 2013 Ad-hoc module of EU SILC on subjective well-being.

Subjective well-being encompasses three distinct but complementary sub-dimensions: life satisfaction, based on an overall cognitive assessment; affects, or the presence of positive feelings and absence of negative feelings; and eudaimonics, the feeling that one’s life has a meaning, as recommended by the OECD Guidelines on Measuring Subjective Well-being. In the Eurostat quality of life framework, all three sub-dimensions are covered.

Main statistical findings

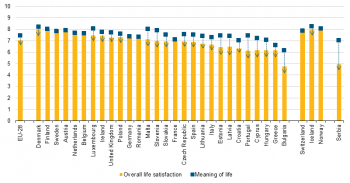

On a scale of 0 to 10 nearly 80 % of European residents rated their overall life satisfaction in 2013 at 6 or higher. This represents an average (mean) satisfaction of 7.1, with values ranging from 4.8 in Bulgaria (followed by Portugal, Hungary, Greece and Cyprus, all at 6.2) to 8.0 in Finland, Denmark and Sweden. Women and men were nearly equally satisfied and younger EU citizens were more satisfied than the other age groups. Unemployed and inactive people were on average the least satisfied (5.8) compared to full-time employed (7.4) or people in education or training (7.8), who reported the highest rates of life satisfaction.

Material living conditions, social relationships and health status are clearly related to life satisfaction. Being at risk of poverty or severely materially deprived is of special relevance here. However, it is a poor health status that impacts on life satisfaction most negatively.

The patterns are mostly the same when looking at meaning of life, which is referred to as the eudaimonic aspect of well-being, though all groups rated the purpose of life on average higher than their overall life satisfaction.

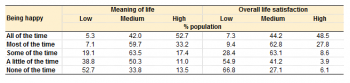

All three aspects of subjective well-being are correlated both at country, as well as at individual level, with some exceptions. In general, people who experienced happiness more often in the last 4 weeks also have a higher probability of high scores regarding meaning of life or life satisfaction, though a considerable proportion of 7.1 % of those “being happy all of the time” reported low levels of life satisfaction.

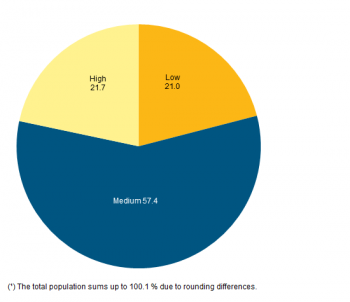

Life satisfaction

Life satisfaction is measured on an 11 point scale which ranges from 0 (“not satisfied at all”) to 10 (“fully satisfied”). For better understanding and interpretation and to facilitate analyses, which identify drivers for low and high satisfaction, answer categories were grouped into low, medium and high. As no theoretical or external criteria were available on an international basis, this classification was based on a 20:60:20 distribution at European level. That means having 20 % of answers in the lower part of the scale, 60 % in the middle and 20 % in the higher part, which leads to the definition of the following thresholds: 0-5 as “low”, 6-8 as “medium” and 9 and 10 as ”high”. The same classification was adopted for all other satisfaction items (like job satisfaction, etc.).

Subjective measures such as life satisfaction and meaning of life today are considered as reliable measures backed by international studies and guidelines. Subjective measures have also turned out to be relatively consistent with objective indicators which function as external validators. Efforts were made to minimise other factors which could cause biases, like for instance mood fluctuations (which should cancel out in large samples[1]) and question order or phrasing (a standard questionnaire was provided to be used in the interview). Nonetheless, some limits remain when interpreting subjective well-being indicators: social desirability of certain answers and normative expectations such as general answering tendencies (e.g. tendency to avoid extreme alternatives) and not least social ideas and opinions of what it means to be satisfied with one’s own life all shape the person’s evaluation of her/his overall life satisfaction[2].

Life satisfaction from a cross country perspective

Figure 1 shows that in 2013 21.7 % of the EU-28 population were highly satisfied with their lives (answering 9 or 10), 57.4 % rated their overall life satisfaction between 6 and 8 and 21.0 % reported a low level of life satisfaction (0-5). One should however bear in mind that the thresholds for life satisfaction levels are defined in this way at European level, as described in the previous paragraph, in order to allow comparisons between countries, socio-demographic groups or different satisfaction items.

Figure 2 shows that the average life satisfaction varied significantly between countries, ranging from 4.8 in Bulgaria to 8.0 in Sweden, Denmark and Finland. Differences between countries in the share of people with low satisfaction were even more remarkable. They ranged from 5.6 % in the Netherlands to 64.2 % in Bulgaria. Proportions of people with high life satisfaction varied from 5.9 % in Bulgaria (followed by Hungary (11.6 %) and Latvia (12.6 %)) to 42.1 % in Denmark. As can be seen in Figure 2 similar averages can reflect different distributions. France and Slovakia reported the same average of 7.0, but Slovakia had much higher proportions of people with both low and high life satisfaction.

How is the socio-demographic background associated with life satisfaction?

Previous research has shown that subjective well-being as measured through overall life satisfaction is very much shaped by socio-demographic factors such as age[3], income[4] or education[5] which lead to different living situations as well as to different expectations and preferences. The analysis below considers how such factors relate to the level of life satisfaction of EU residents.

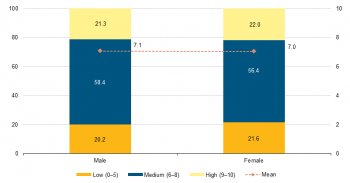

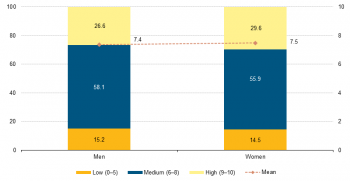

Marginal gender effects on life satisfaction

As shown in Figure 3, women rated their overall life satisfaction slightly lower than men (mean of 7.0 vs. 7.1). Interestingly, the proportion of women with a high level of life satisfaction (22.0 %) was slightly above that of men (21.3 %). On the other hand, marginally more women than men reported low levels of life satisfaction (21.6 % vs. 20.2 %). This might lead to the conclusion that generally speaking, men and women are equal in terms of life satisfaction. However, when controlling for other variables such as income, marital status, labour market position etc. (in a regression analysis), women are still more satisfied with their lives than men[6]. The difference remains however very small.

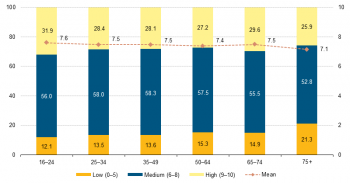

Younger people tend to report higher levels of life satisfaction

As can be seen in Figure 4, life satisfaction was highest among the youngest age group in 2013. It decreased with rising age, with the exception of the age group 65-74, which is for most people the period right after retirement, with averages slightly higher than for those aged between 50 and 64 (7.0 vs. 6.9). This “retirement-effect” can be seen in the majority of the participating countries (Table 1), with the exception of eight (mainly central and southern EU Member States: Bulgaria, Greece, France, Croatia, Italy, Latvia, Poland and Romania), where people in the age group 65-74 did not report higher life satisfaction than those aged between 50 and 64[7]. However, in most EU Member States, the youngest age group reported the highest scores of life satisfaction, exceptions being Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Switzerland and Norway where people 65 or older were even more satisfied than the young.

The effect of age on life satisfaction is small but statistically significant (also when controlling for other variables). However, it has to be taken into account that health problems in older ages play a crucial role and that age itself is not the driving force here. Cohort effects also have to be taken into account when examining age differences: people of the same age-group in a certain country belong to the same generation, lived their active lives in a certain time and experienced wars and peaceful periods in similar periods of their lives. As a consequence, the fact that people in the age group 65-74 are more satisfied with their lives does not imply that a person who is 58 today has a higher probability to be more satisfied with his/her life when turning 68.

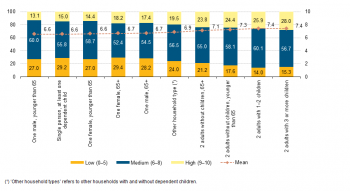

Life satisfaction is higher among couples with children

Figure 5 shows that life satisfaction of people living alone is below the average level of couples (with and without children). Two adults living with children reported the highest levels for life satisfaction (7.4). The lowest average values of life satisfaction, on the other hand, can be observed for one-person households younger than 65 and lone parent households (both 6.6).

Single females aged 65+ most frequently reported a low level of life satisfaction (29.4 %), followed by lone parent households (29.2 %). On the other end of the scale, people living in a couple with three or more dependent children, 28.0 % reported a high level of life satisfaction, and only 15.3 % a low.

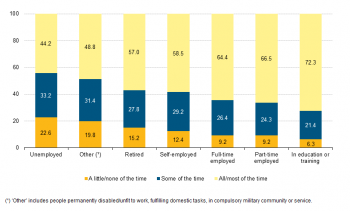

Unemployment is associated with very low life satisfaction

Figure 6 highlights a clear relationship between labour status and life satisfaction. The part of the population which was actively participating in the labour market or preparing to do so, such as those in education or training were more satisfied with their lives on average than the unemployed, retired or other groups.

The lowest level of overall life satisfaction (5.8) was reported by the unemployed, which is 2 points lower than the level of people in education and training (7.8). Within the group of employed, life satisfaction was slightly lower for employees working part-time (7.3) than for their full time counterparts (7.4). Given the high proportion of part-timers that were not voluntarily choosing this schedule in many countries, the difference between these two groups should not be overstated.

In almost all EU Member States people in education or training reported the highest life satisfaction averages in 2013, exceptions being only Denmark, Finland and Ireland, where people in full time employment were more satisfied.

Of all socio-demographic variables unemployment has the most negative impact on life satisfaction. This is true for nearly all EU Member States. EU-wide 43.6 % of this group reported low life satisfaction, and were thus more than three times as likely to rate their life satisfaction low than for instance the full-time employed for which the equivalent was only 14.2 %.

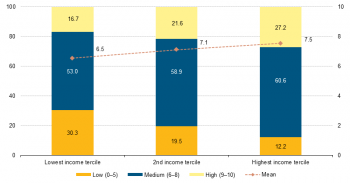

Life satisfaction is clearly associated with income

The analysis of the relationship between income and life satisfaction has a long tradition in empirical research of well-being. First papers date back to the 1970s. One of the first to investigate the empirical relationship between income and life satisfaction, both as regards the individual and at country level, was Easterlin (1974). He observed that wealthier persons were happier than poorer ones in a country and that on average wealthier countries report higher subjective well-being than poorer ones, which is common ground today and has been confirmed by many studies (e.g. Diener 1984, Boarini et al. 2012, p.10). However, it was also shown by Easterlin that despite economic growth, average scores of subjective well-being stayed approximately constant over that period. This could lead to the conclusion that increasing income is generally accompanied by an increase in life satisfaction, but only up to a certain point (also known as rule of diminishing utility e.g. Sacks et al. 2010).

It emerges also from the data analysed in this article that higher income is related to higher scores of life satisfaction. As can be seen in Figure 7, people in the lowest income tercile had the lowest average score (6.5) compared with the other income groups (2nd tercile: 7.1, highest tercile: 7.5).

Only 16.7 % of persons in the lowest tercile reported that they were very satisfied with life in contrast to 27.2 % of the population in the highest income group. Low life satisfaction was reported by 30.3 % of people in the lowest income tercile compared with 12.2 % in the highest.

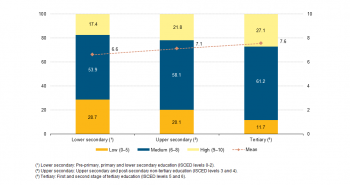

Strong effect of education on life satisfaction

Education is not only an economic resource enabling people to get satisfying and better paid jobs. Many people see education as a value in itself. So it would not be surprising if higher educational levels turned out to be positively related with subjective well-being. However, scientific studies draw a diverse picture. Some researchers found a positive relationship between educational attainment and life satisfaction on an individual level[8], others found a negative relationship particularly for the older population[9]. At an aggregated level, Cheung & Chang (2009) provided evidence that life satisfaction is higher in countries where people spend on average more years in education[10].

Using EU-SILC data, higher educational attainment seems to engender higher levels of life satisfaction (reflecting differences for life satisfaction from an average of 6.6 for people with at maximum lower secondary education, to an average of 7.6 for those with tertiary education) (see Figure 8). This can probably be at least partly accounted for by the fact that higher education leads to better jobs and higher income, which in turn leads to higher life-satisfaction.

These patterns, however, vary significantly between Member States. There was for instance no difference in average life satisfaction between people with tertiary and lower secondary education in Sweden in 2013 and only a very marginal difference of 0.1 points in Denmark, while the differences amounted to 2.0 points in Bulgaria or 1.6 points in Hungary and Croatia. See: Income and living conditions (ilc), EU-SILC ad hoc modules (ilc_ahm), 2013 - personal well-being indicators (ilc_pwb).

What are other important drivers of life satisfaction? Objective / subjective

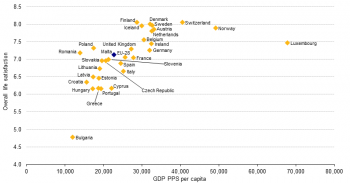

As already discussed, there are regional patterns of subjective well-being. Most of the countries with lower life satisfaction were in the near past, and still are characterised by a low level of income (as indicated for example by PPS adjusted GDP per capita). Possibly also important is the fact that a significant part of the population, the older generations, had experienced lasting and dramatic reversals in the economic, social, welfare and political circumstances of their lives.

As the highest levels of satisfaction were recorded in the northern EU Member States and very low levels could be found in eastern and southern Member States which suffered strongly from the economic crisis and/or have a weak economic situation, the question arises if average life satisfaction is associated with the general economic situation of a country. As shown in Figure 10 for most countries there seems to be a positive association between GDP and overall life satisfaction. Outliers can be found at both ends of the distribution of life satisfaction: Luxembourg, Norway and Switzerland show high values of overall life satisfaction but they are not as high as a potential linear relationship between GDP and average life satisfaction would imply. However, other factors may be at play as well, especially in the case of Luxembourg[11]. On the other end of the scale Bulgaria shows even lower life satisfaction than to be expected by its low GDP. The GDP of Romania is comparable to that of Bulgaria but residents of Romania rate their life satisfaction much higher on average than their Bulgarian counterparts.

Life satisfaction and objective indicators

As is known from a huge body of literature, life satisfaction is not only associated with socio-economic factors, but also and particularly with living conditions and health. In the following section, some of these relationships will be examined.

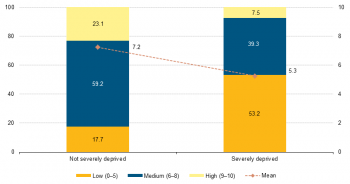

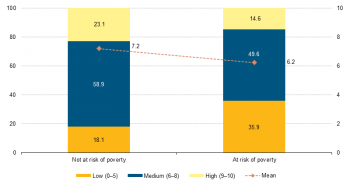

More than half of severely materially deprived EU citizens report a low level of life satisfaction

Severely materially deprived persons have living conditions greatly constrained by a lack of resources and cannot afford at least four out of 9 items: to pay rent or utility bills; to keep their home adequately warm; to pay unexpected expenses; to eat meat, fish or a protein equivalent every second day; a one week holiday away from home; a car; a washing machine; a colour TV; or a telephone. Together with the “at-risk-of poverty rate” and the indicator “low work intensity” severe material deprivation forms the Europe 2020 indicator “at risk of poverty or social exclusion”[12]. At EU level, 9.6 % of the population were affected by severe material deprivation in 2013, 16.6 % were at risk of poverty and 10.8 % of the population aged between 0 and 59 lived in households with very low work intensity. Overall, 24.4 % reported at least one of these problems and were thus at risk of poverty or social exclusion.

Figure 10a demonstrates that there is also a clear relationship between being severely materially deprived and overall life satisfaction, the non-deprived population being on average 1.9 points higher than those severely deprived (7.2 vs. 5.3). This difference is mainly due to the particularly low proportion of very satisfied persons (7.5 %) and very high proportion of those with a low level of life satisfaction (53.2 %) among the severely deprived. The risk of monetary poverty, illustrated in Figure 10b, leads to lower life satisfaction as well, but to a far lesser extent.

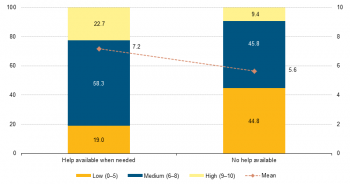

Social relationships

As already indicated in the section on household types, supportive personal relationships play an important role in life satisfaction. In the SILC module 2013 they were covered by two items: “having anyone to discuss personal matters with” and “getting help from others when needed”. Both items show very similar patterns, as shown in Figure 11 for social support, which is highly associated with life satisfaction. More than double the proportion of people who cannot count on friends or family when help is needed had a low level of life satisfaction in 2013 (44.8 % vs. 19.0 %). Only 9.4 % of this group reported high levels of life satisfaction compared with 22.7 % of those who had help available. Fortunately, the share of those who did not have someone to rely on for help or to discuss personal matters with was rather small (6.7 % at EU level for the former and 7.1 % for the latter).

Life satisfaction is strongly associated with health

EU-wide, 67.7 % reported a very good or good health status, while 9.5 % of the population perceived their health status as bad or very bad in 2013. As shown in Figure 12 subjective assessment of one`s own health is a very good predictor for overall life satisfaction, with the proportion of people with low life satisfaction going up as self-perceived health goes down. The opposite is true for the proportion of people with high life satisfaction. While in the group reporting very good health 36.9 % showed high life satisfaction, there were only 7.1 % with high life satisfaction in the group with very bad health. It seems to be possible to have a good life even in very bad health, although the probability is more than 5 times lower than for those in very good health.

With a proportion of people with low satisfaction of 65.9 % in the group with very bad health, health status is the most notable predictor for general life satisfaction. Nothing, not even unemployment or material deprivation, puts life satisfaction in danger as much as bad health. The average score varied from 7.9 for people who said they were in very good health to 4.5 for those with a very bad health status.

Meaning of life and happiness

As already mentioned, subjective well-being encompasses three distinct but complementary sub-dimensions: life satisfaction (or evaluation), based on an overall cognitive assessment; affects or the presence of positive feelings and absence of negative feelings and eudaimonics, the feeling that one’s life has sense and purpose. Evaluation has already been discussed above. In this part the other two aspects are first analysed and broken down by selected socio-economic variables, and then how the three aspects are interrelated is examined. In addition, the following part is devoted to the question of what is measured by these three different variables and how it relates to the full picture of subjective well-being.

Meaning of life

In the EU-SILC 2013 data we observe that meaning of life shows an almost identical pattern as life satisfaction, with the difference, however, that meaning of life is consistently rated higher by all groups than life satisfaction. This is true when looking at socio-demographic variables but also when comparing life satisfaction and meaning of life broken down by more objective items such as material deprivation or risk of poverty. Nevertheless, the differences in the average rating between the groups who faced a specific disadvantage and those who did not are much smaller for meaning of life than for life satisfaction. One could therefore conclude that the evaluative part of subjective well-being in a way summarises concrete domain specific satisfactions, while the question of a purpose or meaning in life is answered on a more – even if not total – abstract level.

Compared to life satisfaction, people generally were more positive regarding the meaning of life. Figure 13 shows that 28.2 % of the total EU-28 population rated the meaning of life at a high score (9 and 10), 56.9 % assessed it between 6 and 8 and 14.9 % reported a low level of meaning of life (0-5).

Meaning of life by selected socio-demographic variables

Women on average reported slightly higher levels of meaning of life (which is the other way around than life satisfaction). Males had an average value of 7.4 and females of 7.5. Significantly more women than men reported high levels of meaning of life (29.6 % vs. 26.6 %), while there were negligible differences at the bottom of the distribution.

Compared with life satisfaction, the average meaning of life was quite constant across the various age groups in 2013, ranging between 7.4 (age group 65-74) to 7.6 (16-24). The exception, however, was the oldest group of people aged 75 or older who reported an average score of 7.1, showing a significantly lower level of meaning of life.

The proportion of low meaning of life very slightly increases with age, but is by far the highest in the oldest age group (21.3 %). Proportions of high levels are quite constant between the ages 25 and 74 and were most frequently reported by people aged between 16 and 24 (31.9 %).

The interrelation of life satisfaction and meaning of life

How are meaning of life and overall life satisfaction related? Do they measure the same or at least a similar construct?

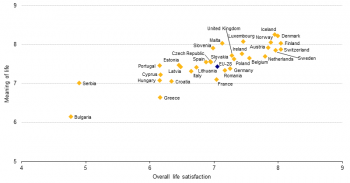

When looking at both items together at country level, it can be observed that Member States with the highest average values of life satisfaction recorded similar averages for both items, like Finland (average value of 8.0 for both life satisfaction and meaning of life), Austria (average value 7.8 vs 7.9), the Netherlands (average value 7.8 vs 7.7), Sweden (average value 8.0 vs 7.8) and Denmark (average value 8.0 vs 8.2)(see Figure 16). In most other EU Member States, people rated the meaning of life significantly higher than their life satisfaction. The gap between the two items was larger in Member States where life satisfaction was low, with the biggest differences being observed in Bulgaria (1.4 points), Portugal (1.3 points) and Cyprus (1.1 points).

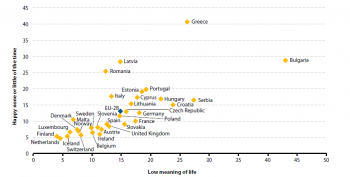

Overall, the eudaimonic aspect of well-being is more concentrated around the average than life satisfaction. As shown above, in most countries the meaning of life is rated higher than general life satisfaction. Figure 17 shows that countries with low average levels of life satisfaction, such as Bulgaria or Greece, also reported comparable low values for meaning of life and the other way round: a higher average for overall life satisfaction is associated with higher rates for meaning of life. Although Figure 17 shows no perfect correlation, the connection is quite strong. There are exceptions as well. Portugal, which was among the countries with the lowest level of life satisfaction (6.2) in 2013, actually had an average value of meaning of life of 7.5 which is above the EU-28 average (7.4). French residents, on the other hand, rated their life satisfaction and their meaning of life at the same level (7.1), equal to the EU average for the former, but among the lowest averages in the EU for the latter.

Deviations from the regression line need to be further examined, but might also be due to language specificities (the concepts of “meaning” and “satisfaction” being interpreted differently in different languages) or other cultural effects.

Happiness

Happiness was measured in EU-SILC by the following question: “How much of the time over the past four weeks have you been happy?” Although this question was asked on a verbal 5 point scale in the EU-SILC 2013 and can thus not be directly compared with life satisfaction, we observe similar patterns regarding differences between various groups. However, the differences between groups who reported disadvantages in a specific domain and those who did not were not as pronounced regarding happiness as for life satisfaction.

Figure 18 shows that nearly 6 in 10 EU residents said that over the last four weeks they were all or most of the time happy. Almost a third of the EU population was happy some of the time and 13 % were happy only a little or none of the time.

Frequency of being happy in the last 4 weeks by selected socio-demographic variables

As can be seen in Figure 19, happiness (as for life satisfaction and meaning of life) is highest among the youngest age group (16-24) with a proportion of 71.5 % reporting to have been happy all or most of the time over the last four weeks. It then decreases until the age of 50-64, goes slightly up again between 65-74 and reaches its lowest level in the 75+ group which has the highest proportion of people who were “happy little or none of the time” (17.9 %).

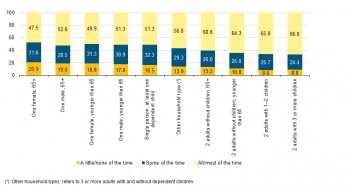

Figure 20 illustrates that generally two adult households (in many cases couples) were happier than people living on their own and that households with children were the happiest (with the exception of single parents who report rather low happiness levels). 66.8 % of people living in households with two adults and three children and 65.8 % with two adults and one or two children were happy all or most of the time. At the other end of the scale, women aged 65 or older living alone were the most often unhappy with a proportion of 20.9 % who said that they were happy little or none of the time (followed by males older than 65 (19.0 %) and female one-person households younger than 65 (18.8 %)).

People who were in education and training were the most often happy with more than 7 in 10 answered that they were happy all or most of the time over the last four weeks, followed by part-time employees (66.5 %) and full-time employees (64.4 %). Full-time employees consequently reported a slightly lower level of happiness than part-time employees while their life satisfaction was on average slightly higher than for part-time employees. On the other hand, unemployment has not only negative consequences for life satisfaction and meaning of life but also severe impacts on happiness. 22.6 % of the unemployed said that they were happy little or none of the time.

Interrelations of happiness and the other two aspects of subjective well-being

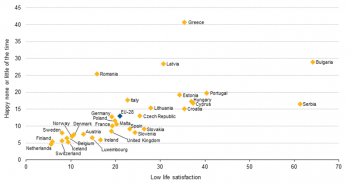

Figure 22[13] illustrates the relationship between low life satisfaction and low happiness (being happy none or little of the time) showing a fairly linear association, exceptions being Romania, Latvia and Greece, where the proportion of the population being happy little or none of the time was higher than expected. Three main groups can be identified: Group 1 containing countries with low proportions in both items, group 2 (including the EU-28 average) with medium levels and group 3 with relative high proportions of low satisfaction and low happiness (including Estonia and Portugal).

The picture is not as clear when looking at the proportion of people “being happy none or little of the time” and “low meaning of life” as shown in Figure 23, though the pattern is quite comparable. For instance, the outliers are again Romania, Latvia and Greece. However, the three clear-cut groups disappear. There is one group of Member States, including those with proportions of people being happy none or little of the time between 4.6 % in the Netherlands and 8.4 % in the United Kingdom and proportions of low meaning of life ranging from 4.0 % in Finland to 12.9 % in the United Kingdom. The other group of countries displayed proportions of low happiness ranging from 10.0 % in France to 19.7 % in Portugal and low meaning varying from 14.7 % in Poland to 23.8 % in Croatia.

It can be concluded that there is an observable relationship between happiness and satisfaction at least at country level. And what about individuals? Were people who had been happy most or all of the time in the last four weeks before the interview highly satisfied with their life? Table 2 shows that in general this was the case: a person who experienced happiness more often in the last 4 weeks had a higher probability of a high score for life satisfaction. 76.3 % of those who reported that they were happy most or some of the time also rated their life satisfaction high. On the other hand, there was a group for which life satisfaction was not associated with happiness. 7.3 % of those who were happy all the time rated their overall life satisfaction between 0 and 5, which is regarded as low. In addition, 6.1 % of those who were happy none of the time reported a high life satisfaction, and 13.5 % of people in this group even reported high values regarding meaning of life. So it can be concluded that while life satisfaction does not measure the same as happiness, of course the two are correlated.

Data sources and availability

An ad-hoc module on subjective well-being was implemented in the EU-SILC 2013. This module contains subjective questions (e.g. How satisfied are you with your life these days?) which complement the mostly objective indicators from existing data collections and social surveys.

The "GDP and beyond" communication, the SSF Commission recommendations, the Sponsorship on measuring progress, and the Sofia memorandum all underlined the importance of collecting high quality data about people's quality of life and well-being and the central role that statistics on income and living conditions (SILC) have to play in this improved measurement. The collection of micro data related to well-being therefore is a key objective. In May 2010 both the Living Conditions Working Group and the Indicators Sub-Group of the Social Protection Committee supported Eurostat's proposal to collect micro data related to well-being within the 2013 module of SILC in order to better respond to this request.

For more information please visit: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/gdp-and-beyond/quality-of-life/context

Context

Life satisfaction

Life satisfaction represents how a respondent evaluates or appraises his or her life taken as a whole. It is intended to cover a broad, reflective appraisal the person makes of his or her life. The term «life» is intended here as all areas of a person’s existence[14]. The variable therefore refers to the respondent’s opinion/feeling about the degree of satisfaction with his/her life. It focuses on how people are feeling "these days" rather than specifying a longer or shorter time period. The intent is not to obtain the current emotional state of the respondent but to receive a reflective judgement on their level of satisfaction. Veenhoven (1991, 3) notes that “life satisfaction is conceived as the degree to which an individual judges the overall quality of his/her life-as-a-whole favourably“. This is in line with Pavot and Diener (2008, 137) who define life satisfaction as a “distinct construct representing a cognitive and global evaluation of the quality of one’s life as a whole“. Some economists also discuss the question if satisfaction is the same as utility[15].

While indicators like job satisfaction, satisfaction with the financial situation of the household or satisfaction with the accommodation address certain areas of life, general life satisfaction refers to the individual’s evaluation of all subjectively relevant life domains and is therefore considered as an overall measure for subjective well-being.

Meaning of life - an eudaimonic measure

Meaning of life is a multi-faceted construct that has been conceptualised in diverse ways[16]. It refers broadly to the value and purpose of life, important life goals, and for some, spirituality. The respondent should be invited to think about what makes his/her life and existence important and meaningful and then answer to the question. It is not related to any specific area of life, focuses rather on life in general and refers to the respondent’s opinion.

In the EU-SILC 2013 ad-hoc module (AHM) the item «meaning of life» covers the eudaimonic dimension of subjective well-being. «Eudaimonic»[17] refers to purpose and meaning in life. It is therefore also referred to as the psychological or «functioning» approach[18] to subjective well-being. The meaning of life item intends to capture important factors that are not necessarily measured by evaluative measures such as life satisfaction including purpose, sense of meaning or autonomy. However, as will be seen from the analysis below, the pattern of this item is quite in line with the life satisfaction, though in general people tend to rate their « meaning of life » higher than their life satisfaction.

Happiness - emotional aspect of well-being

The emotional aspect of well-being refers to people’s day-to-day feelings and moods. For this kind of measures, respondents are typically asked to think about their feelings in question (such as happiness or sadness) within a short time period. Large sample sizes and high survey quality should ensure that population estimates are not systematically biased due to temporal variability of moods etc.

In EU-SILC the period on which the respondent should reflect was limited to the last four weeks before the interview. Both positive and negative feelings were measured including happiness, depression, stress and others. In this article, however, we will only focus on a question on happiness. Respondents were invited to answer the following question: “How much of your time over the past four weeks have you been happy?”. They could choose among five answering categories (ranging from “all of the time” to “none of the time”).

In this article overall life satisfaction will have a prominent role as it can be regarded as a key indicator for subjective well-being. First the distribution in general and for different countries will be shown. Then the association of socio-demographic variables such as age, gender, income or household type with overall life satisfaction will be examined. In a further step, the article will look at other relevant variables such as material living conditions and their relation to life satisfaction. In the final part the subjective well-being dimensions meaning of life and happiness are covered and it is discussed how they are related to life satisfaction. Relevant EU-policies are discussed in the concluding section.

EU policies targeting subjective well-being

Measuring well-being has an inherent appeal: it is arguably the ultimate aim of all EU policies, and the common thread that runs through them all. Promoting the well-being of people in Europe is one of the principal aims of the European Union, as set forth by the Treaty on European Union.

Today, in the European Union a broad range of outcomes is considered when evaluating the objectives of social and economic policy including subjective measures of quality of life. Many EU bodies but also Member States themselves report on subjective well-being and publish associated reports going beyond GDP as the overall measure of societal performance.

Well-being began to appear more explicitly at the EU policy agenda in 2006 when the Council of the European Union cited the well-being of present and future generations in its European Sustainable Development Strategy as its central goal[19]. Soon after that the limits of GDP as a measure of well-being were more and more discussed at the international level flowing into the “Beyond GDP” initiative followed by a Conference in the European Parliament in 2007. In 2009 the European Commission published its Communication on “GDP and beyond – measuring progress in a changing world” concluding that EU policies will be ultimately judged on the question if they successfully delivered social, economic and environmental goals[20]. In the same year, the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress (Stiglitz-Commission) published its Report. The so called Stiglitz Report was also the basis for the work of the ESS (European Statistical System) Sponsorship Group on Measuring Progress, Well-being and Sustainable Development which published its report in 2011.

See also

- All articles on living conditions and social protection

- Quality of life indicators (online publication)

Further Eurostat information

Main tables

- Income distribution and monetary poverty (t_ilc_ip)

- Monetary poverty (t_ilc_li)

- Monetary poverty for elderly people (t_ilc_pn)

- In-work poverty (t_ilc_iw)

- Distribution of income (t_ilc_di)

- Material deprivation (ilc_md)

- Material deprivation by dimension (t_ilc_mddd)

- Housing deprivation (t_ilc_mdho)

- Environment of the dwelling (t_ilc_mddw)

Database

- Income distribution and monetary poverty (ilc_ip)

- Monetary poverty (ilc_li)

- Monetary poverty for elderly people (ilc_pn)

- In-work poverty (ilc_iw)

- Distribution of income (ilc_di)

- Material deprivation (ilc_md)

- Material deprivation by dimension (ilc_mddd)

- Economic strain (ilc_mdes)

- Economic strain linked to dwelling (ilc_mded)

- Durables (ilc_mddu)

- Housing deprivation (ilc_mdho)

- Environment of the dwelling (ilc_mddw)

- EU-SILC ad hoc module (ilc_ahm)

Dedicated section

Methodology / Metadata

- Income and living conditions (ESMS metadata file — ilc_esms)

Source data for tables and figures (MS Excel)

Other information

- References

- Diener, E.D. & Tov, W (2011). National accounts of well—being. KC Land, AC Michalos 8, 137-158

- Tinkler, L und Hicks, S. (2011). Measuring Subjective Well-being. London: Office for National Statistics

- Oguz, S., Merad, S. & Snape, D. (2013). Measuring National Well-being – What matters most to Personal Well-being? Office for National Statistics, London

- Burchardt, Tania (2003): Identifying adaptive preferences using panel data: subjective and objective income trajectories. Paper prepared for 3rd Conference of the Capability Approach. 7.-9. September 2003, Pavia

- Baber, H. E. (2007). Adaptive preference. Social Theory and Practice 33 (1):105-126

- Teschl, M., & Comim, F. (2005). Adaptive preferences and capabilities: some preliminary conceptual explorations. Review of social economy, 63(2), 229-247

- Sacks W. D., Stevenson, B. &Wolfers, J. (2010). Subjective Well-being, Income, Economic Development and Growth, NBER Working Paper No 16441, National Institute of Economic

- Boarini, R., Comola, M., Smith, C., Manchin, R. & de Keuenaer, F. (2012). What Makes for a Better Life?: The Determinants of Subjective Well-Being in OECD Countries – Evidence from the Gallup World Poll. OECD Statistics Working Papers, 2012/03, OECD Publishing

- Cárdenas, M. & Mejía, C. (2008). Education and Life satisfaction: Perception or Reality? Draft Paper, Universitá degli Studi di Napoli Parthenope

- Research

- Salinas-Jiménez, M.M., Artés. J. & Salinas-Jiménez, J. (2010). Education as a Positional Good: A Life Satisfaction Approach. Social Indicators Research, 103(3), 409-426

- Cuñado, J. & F. Pérez-de-Gracia (2012). Does Education Affect Happiness? Evidence for Spain. Social Indicators Research, 108(1), 185-196

- Gong, H., Cassels, R. & Keegan, M. (2011). Understanding Life Satisfaction and the Education Puzzle in Australia: A profile from HILDA Wave 9. NATSEM Working Paper 11/12

- Cheung, H & Chan, A.W.H. (2009). The Effect of Education on Life Satisfaction Accross Countries. The Alberta Journal of Educational Research 55 (1), 124-136

Notes

- ↑ The total sample size covering the EU-28 plus Switzerland, Iceland, Norway and Serbia is around 366650 individuals and ranges approximately from 25500 in Spain to 5200 in Denmark and 2950 in Iceland

- ↑ e.g. Diener & Tov 2011, Tinkler & Hicks 2011, Oguz et al. 2013

- ↑ e.g. Helliwell 2008

- ↑ e.g. Boarini et al. 2012, Sacks et al. 2010

- ↑ Cárdenas & Mejía 2008, Salinas-Jiménez et al. 2010, Cuñado & Pérez de Gracia 2012

- ↑ This is also confirmed in other international studies such as Boarini et al. 2012

- ↑ The official retirement age is currently between 60 (in France) and 65 (eg: Benelux countries, Germany, Ireland, Spain) in most EU Member States. In some Member States (for example Austria, Poland, Italy, Greece and the UK) women can retire 5 years earlier than men

- ↑ e.g. Cárdenas & Mejía 2008, Salinas-Jiménez et al. 2010, Cuñado & Pérez de Gracia 2012, Boarini et al. 2013

- ↑ Gong et al. 2011

- ↑ Years of education are predicted by enrolment rates at the secondary and tertiary levels

- ↑ The GDP per capita of Luxembourg is artificially high, as a high proportion of people working in Luxembourg live abroad in the neighbouring countries, so they contribute to GDP creation but are not counted when distributing it per capita

- ↑ European Commission (2014): Smarter, greener, more inclusive? Indicators to support the Europe 2020 strategy, 2015 edition, page 145

- ↑ The direction of the axis is to be read as follows: the lower the values the better – low proportions of “low life satisfaction” and of “happy none or little of the time” are positive

- ↑ E. Diener, Guidelines for National Indicators of Subjective Well-Being and Ill-Being

- ↑ e.g. Lévy-Garboua 2007, Holländer 2001

- ↑ For an overview see Klemke, Elmer Daniel. "The meaning of life." (2000)

- ↑ Etymologically, eudaimonia consists of the words "eu" ("good") and "daimōn" ("spirit"). It is a central concept in Aristotelian ethics where it was used as the term for the highest human good.

- ↑ Nussbaum 1986

- ↑ Council of the European Union, 2006

- ↑ European Commission, 2009