Archive:Quality of life in Europe - facts and views - education

This articles has been archived. The paper format and the PDF format latest edition, ISBN 978-92-79-43616-1, doi:10.2785/59737, Cat. No KS-05-14-073-EN-N are still available. For updated information on quality of life - education, see the online publication Quality of life indicators - education.

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfse_14)

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfse_14)

Source: Eurostat (edat_aes_l22)

Source: Eurostat (edat_aes_l32)

Source: Eurostat (isoc_sk_iskl_i)

Source: Eurostat (isoc_sk_iskl_i)

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfs_9903)

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfs_9903)

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfs_9903)

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfs_9903)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_di08)

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfs_9904)

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfs_9905)

Source: Eurostat (EU SILC)

Source: Eurostat (EU SILC)

Source: Eurostat (EU SILC)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_pw01)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_pw06)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_pw01)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_pw01)

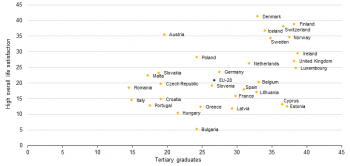

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfs_9903) and (ilc_pw01)

This article on education is the third in a series of nine articles dedicated to the quality of life of people in the European Union (EU) and is part of a set of articles forming the publication Quality of life in Europe - facts and views.

The first part of the article focuses on the analysis of educational attainment indicators (including the prevalence of early education and early school leaving) as well as of self-reported expertise and skills, such as the knowledge of foreign languages and digital literacy. It is followed by an analysis of the variation of educational attainment between EU Member States by various socio-demographic variables such as age, sex, income, labour status and occupation.

Main statistical findings

Statistical findings in other articles of this publication have indicated that job satisfaction and overall life satisfaction were higher amongst tertiary graduates (See article 2 on employment). Based on this, the last part of the article examines education as a determinant of the quality of life of individuals, looking at the relations between educational attainment and various aspects of well-being at EU level and in the EU Member States.

Education in a quality of life perspective

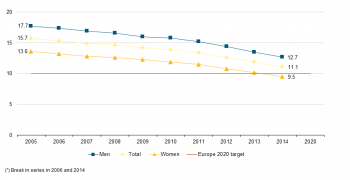

In 2014, there were about 4.6 million early leavers from education and training (aged 18-24) across the EU-28. These people were at great risk of deprivation and social exclusion, as about 41 % of them were jobless[1]. Since 2005, the share of early leavers has fallen continuously in the EU, from 15.7 % in 2005 to 11.1 % in 2014. Almost all EU Member States experienced the same trend. Nonetheless, the EU-28 as a whole still finds itself 1.1 percentage points above the 10 % target that it set itself for the year 2020.

This positive trend can to some extent be attributed to the progress in pre-primary education which is considered a first policy lever to prevent early school leaving. In 2012, the EU-28 was only 1.1 percentage point away from its 95 % benchmark on pre-primary education which was already universal in a few EU Member States.

The EU-28 was performing better in terms of ICT skills — the percentage of those who had never used the internet was halved from 43 % to 21 % between 2005 and 2013. An important divide in computer literacy between northern/central EU Member States and southern/eastern EU Member States continued to subsist however.

About one third of the EU population (34.3 %) reported not to know any foreign language in 2011, ranging from 72.7 % in Ireland to 1.1 % in Luxembourg. Out of the remaining population (those speaking at least one foreign language) more than half reported either a good or a proficient level of knowledge of their best-known foreign EU language, but figures at country-level were again quite diverging.

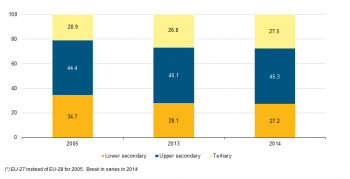

There has been a decline in the percentage of the population aged 25–74 having completed lower secondary education only (from 34.7 % in 2005 to 28.1 % in 2013 and even to 27.2 % in 2014) linked to an increase in tertiary educational attainment (which grew for the same age group from 20.9 % in 2005 to 26.8 % in 2013, even to 27.5 % in 2014) in the EU-28. The proportion of women with tertiary graduates (aged 25–74) outweighed men by 1.2 percentage points (27.3 % versus 26.1 %) in 2013. Most tertiary education graduates were found amongst the younger age groups (25–34), as well as amongst the most advantaged categories of EU residents, people in employment or occupying managerial positions, professionals and technicians. Income was closely linked with the level of educational attainment.

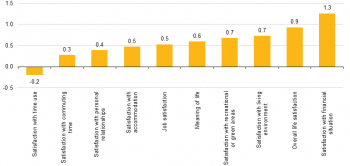

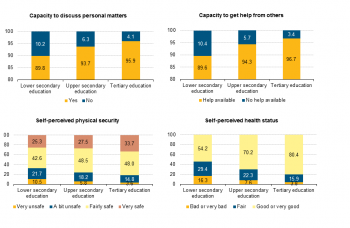

Education appeared to be a strong determinant of subjective well-being: the most educated people in the EU were much less prone to report being down, depressed or nervous, and were happier than the least educated ones. Educational attainment also seems to affect satisfaction with different aspects of life both at EU level and across EU Member States, which the most educated almost systematically assessed more positively. This was particularly true regarding the satisfaction with the financial situation of their household which was superior by around 1.3 percentage points to that recorded by the least educated. Additionally tertiary graduates experienced more rewarding social relationships, felt more secure and in better health. Lastly, their overall rating of life satisfaction and its meaning was higher by 0.9 and 0.6 points rating respectively.

Major achievements in education and skills since 2005

The section below focuses on trends in education and skills achievement since 2005 within the EU-28 as a whole and by country level.

Less and less people were leaving education and training early

There were about 4.6 million early leavers from education and training (aged 18-24) across the EU-28 in 2014. They were potentially at great risk of deprivation and social exclusion, in particular due to the high probability of unemployment they were facing: 41.0 % of the early school leavers were jobless[2].

Figure 1 indicates that since 2005 the share of early leavers from education and training had fallen continuously in the EU-28. From 15.7 % in 2005, it went down to 11.1 % overall in 2014, ranging from 12.7 % for men to 9.5 % for women. Both proportions of men and women early school leavers followed the same tendency and the gender gap remained almost constant between 2005 and 2014. The EU-28 average was still in 2014 1.1 percentage points over the 10 % target set for the year 2020, but the share for women reached that year the target, being 0.5 percentage points below the target.

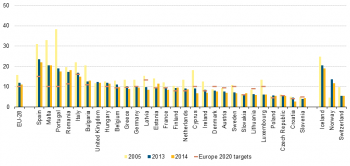

The decline of the number of early school leavers observed at EU-28 level mirrored decreases in almost all EU Member States since 2005 (Figure 2). Member States registering the lowest proportions of early school leavers were mainly from the central and eastern parts of the EU (Slovenia, the Czech Republic, Poland and Croatia). On the other hand, southern EU Member States (such as Spain, Malta, Portugal and Italy) but also Romania and Bulgaria, displayed the highest shares of early school leavers, although their figures improved considerably.

While Malta and Portugal had achieved the sharpest reductions in their share of early school leavers by 2014, they were still some distance away from their Europe 2020 national targets (10.4 and 7.4 percentage points respectively). Spain, which recorded the highest share of early school leavers in 2014 (21.9 %), also achieved one of the sharpest decreases since 2005 (9.1 percentage points), while it was still 6.9 percentage points away from its national target.

More than half of the population reported a good or proficient knowledge of its best-known foreign language

One of the important outcomes of initial education is a proper level of basic expertise as this has an impact on the labour market productivity of the working-age population. However, transversal expertise, such as the ability to communicate in one or more foreign languages or to use the internet and a computer, are becoming crucial qualifications in a rapidly changing labour market and in everyday life. Such skills are expected to increase mobility and employability and to facilitate intercultural dialogue[3].

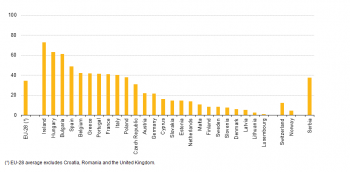

According to the results of the Adult Education Survey, one third (34.3 %) of the EU population aged 25–64 reported that they did not speak any foreign language in 2011. Another third (35.8 %) could speak at least one foreign language, 21.1 % two and 8.8 % three or more. Some progress can be observed compared with the respective shares of 2007, when those who could speak no foreign language at all (39.3 %) or just one (37.2 %) were more numerous, and fewer reported being able to communicate in 2 languages (16.9 %) or more (6.6 %). Age had a decreasing effect on the number of languages spoken: hence a much higher proportion of those aged 55–64 (47.6 %) reported not knowing any foreign language compared with those aged 25–34 (22.8 %) in 2011.

A cross-country analysis reveals diverse situations (Figure 3), where almost no Luxembourgish residents reported not knowing any foreign language (1.1 %), while more than seven in ten Irish residents did not speak any foreign language (72.7 %). Please note that no data were not available for Croatia, Romania and the United Kingdom.

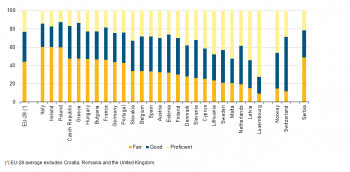

Figure 4 shows the level of the foreign language best-known to a respondent who can speak at least one foreign language, whichever it may be, in 2011. At EU-28 level, more than half of respondents reported either a good (32.7 %) or a proficient (23.4 %) level of knowledge of their best-known foreign language, ‘fair’ being reported by the remaining 43.9 %.

At country level, Italy, Ireland and Poland were the only EU Member States recording shares of respondents with at least good level below 50.0 % (around 40.0 % in each EU Member State when summing up proficient and good). The shares of all the other EU Member States ranged from 52.6 % in the Czech Republic and Greece to 90.5 % in Luxembourg.

The EU population has improved its digital skills

Just as for language skills and other transversal expertise, digital skills are expected to improve employability and social inclusion, by enhancing societal learning, creativity, emancipation and empowerment.

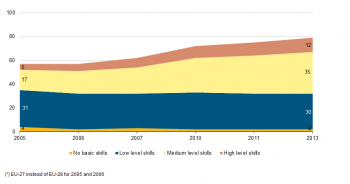

EU policies and initiatives implemented in the field of education and employment and more generally within the context of the Europe 2020 strategy[4], have been tackling the issue of ICT skills (as well as connectivity) at business and citizen levels. However, as Figure 5 denotes, a large part of the EU-28 population was still affected by a deficit in digital literacy, with about 79.0 % reporting to have already used the internet in 2013, but only 12.0 % declaring to have high level skills in its use. While this was a major improvement since 2005, it also meant that in 2013, over 20.0 % of the respondents had never used the internet.

Internet skills

The level of internet skills are measured using a self-assessment approach, where respondents indicate whether they have carried out specific tasks related to internet use, without these skills being assessed, tested or actually observed.

In 2005, 2006, 2007, 2010, 2011 and 2013, six internet-related items were used to group the respondents into levels of internet skills:

- use a search engine to find information;

- send an e-mail with attached files;

- post messages to chat-rooms, newsgroups or any online discussion forum;

- use the internet to make telephone calls;

- use peer-to-peer file sharing for exchanging movies, music etc.; and

- create a web page.

Respondents were classified into four categories:

- No basic internet skills: individuals who have not carried out any of the six internet-related items.

- Low level of basic internet skills: individuals who have carried out one or two of the six internet-related items.

- Medium level of basic internet skills: individuals who have carried out three or four of the six internet-related items.

- High level of basic internet skills: individuals who have carried out five or six of the six internet-related items.

As the questions on skills were only addressed to individuals who used the internet, those who never used computers completed the picture for the whole population.

These favourable trends were also mirrored at country level. Since 2005, the shares of individuals who had carried out three, four, five or six of the six internet-related activities increased in all EU Member States for which data was available.

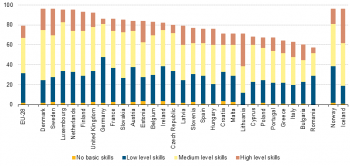

However, there were some national discrepancies in 2013, as shown in Figure 6. The smallest shares of people who have never used the internet (or have not performed any of the listed internet activities) were found in Denmark (6.0 %), closely followed by Luxembourg, Sweden and the Netherlands, whereas the highest shares were recorded in Romania (43.0 %) and Bulgaria (42.0 %). The southern EU Member States (Italy, Greece, Portugal, Cyprus, Malta and Spain), where a higher proportion of the population only had primary or lower secondary education, also registered higher than the EU-28 average shares of people who had never used the internet.

Among those who used the internet, there was also a degree of variation in the skill levels across EU Member States. The share of self-reported low skill level varied between 12.0 % in Lithuania and 46.0 % in Germany. For medium skills, it varied between 22.0 % in Bulgaria and 50.0 % in Denmark while, for high skill level, it was as little as 5.0 % in Germany and Romania and as much as 32.0 % in Lithuania.

Progress in ICT skills was accompanied by substantial increases in broadband internet connections in businesses and households in most EU Member States (In 2014, the share of household connectivity was 78 %; for enterprises it was 90 % in 2013). In spite of these improvements, much remains to be achieved if the EU wants to catch up to its main international competitors. In effect, only half of the so-called ‘digital-native generation’ reported being able to solve more than basic problems in technology-rich environments[5].

Major achievements in educational attainment since 2005

The level of education of EU residents has been improving

Turning the EU into a smart, sustainable and inclusive economy delivering high levels of employment, productivity and social cohesion, requires increasing the overall level of skills and expertise, and hence the level of education of EU residents.

Since 2005, as illustrated in Figure 7 (for people aged 25–74), one can observe a trend towards an increase in the level of educational attainment in the EU. The share of low educated people declined from 34.7 % to 27.2 % in 2014, while the share of tertiary graduates grew from 20.9 % to 27.5 %. Upper secondary education, while still held by the majority, remained almost stable at approximately 44–45 %.

As 2013 is the reference year for the data collected through the EU-SILC ad-hoc module on subjective well-being, the analysis presented below, which aims to link the objective indicators on education with the subjective ones, will not be based on the latest 2014 figures, but on the 2013 ones.

In 2013, the distribution of the EU-28 population by educational level was the following: 26.8 % were graduated from tertiary education, 45.1 % attained the upper secondary education and 28.1 % completed lower secondary education only.

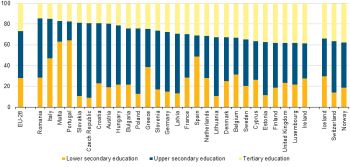

All EU Member States except Denmark (+ 3.6 percentage points) experienced downward trend in the share of people having at most completed lower secondary education since 2005. There was no exception to the upward trend in tertiary education. However, as indicated in Figure 8, as of 2013, there were some notable variations in the percentage of people having completed lower secondary education (ranging from 8.8 % in the Czech Republic to 64.5 % in Portugal). In addition, 18.0 % completed upper secondary education in Portugal versus 72.1 % in the Czech Republic. The percentage of people having graduated from tertiary education ranged from 14.5 % in Romania to 38.7 % in Ireland.

Educational attainment varies across different socio-demographic groups

The socio-economic status was still by far the major element of an individual’s key basic expertise[6]. Against this finding, this section will examine possible correlations between individual educational attainment and belonging to certain socio-demographic groups, broken down by age, sex, income, labour status and occupation.

The 25–34-year-olds were the most educated

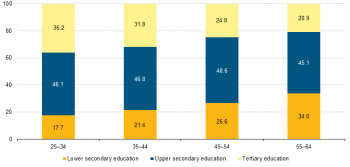

Figure 9 shows that the level of educational attainment of the younger generations was higher than that of the older ones. This was particularly true for the tertiary education level. Among people aged 25–34, 36.2 % had completed tertiary education as opposed to only 18.9 % in the group of people aged 55–74. The trend was inverted for lower secondary education, with percentages declining from 39.7 % for the 55–74 age group to 17.7 % for the 25–34 age group.

These differences across age groups represented a structural trend and were mainly the result of an increased focus on education in recent decades, driven by technological changes and the development of knowledge-based societies and economies. The adoption of EU policies such as Europe 2020 and its predecessor, the Lisbon strategy[7], also played a part in these recent developments.

There were more female than male tertiary graduates

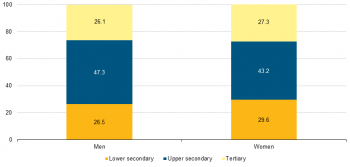

When looking at male and female educational attainment in 2013 (Figure 10), women appeared to perform better than men in terms of tertiary education by 1.2 percentage points (27.3 % versus 26.1 %). However, more women than men had completed lower secondary education (29.6 % versus 26.5 %), while more men than women held upper secondary degrees (47.3 % versus 43.2 %).

A more in-depth analysis of the most and least educated age groups (those aged 25–34 and 55–74 respectively) (for which data is available), reveals that young adult women (25–34) exceeded the proportion of highly graduated men by almost 10 percentage points in that age group (41.1 % versus 31.5 %). However, they were outperformed by men in the 55–74 age group (16.5 % for women versus 21.6 % for men). Differences in the other education levels (lower and upper secondary) were less apparent. The explanation mostly lies in changing ways of life observed in recent decades which have encouraged women to further their education with a view to increasing their participation in the labour force and in civil society.

Education attainment was linked to pronounced income inequalities

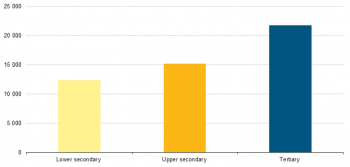

As can be seen in Figure 11, the level of education attained clearly affected income levels of the EU population. The median income of lower secondary education graduates (EUR 12 721) was almost one fourth/one fifth lower than that of upper secondary education graduates (EUR 15 275) and half that of tertiary graduates (EUR 21 769).

Low educational attainment was mainly found amongst the unemployed and inactive

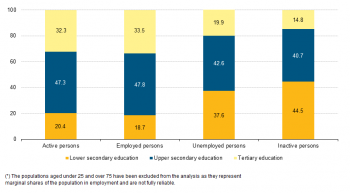

As Figure 12 shows, for around half of the EU employed population (aged 25–74), upper secondary education was the highest educational attainment. The other types of education were less evenly distributed across labour status categories. The highest proportion of low educated people (44.5 %) was found amongst inactive persons. This group includes people outside the labour market — those still in education (and not yet graduated) or retired, or inactive on other grounds (personal/family reasons, health status, lack of employability. Amongst the group of active people, the impact of education on employability is pronounced with the unemployed making up the category with highest share of low educated people (37.6 %) with, on the contrary, the employed recording the highest shares of tertiary graduates (33.5 %).

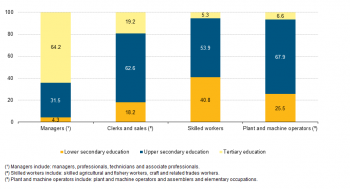

Educational attainment varied considerably across categories of employees

Figure 13 puts into light a strong link between an individual’s level of education and class of occupation. Available figures about employees reveal that around two thirds of managers (64.2 %) had graduated from higher education whereas more than half of the employed in the other three categories had mainly completed upper secondary education (with shares varying from 53.9 % for skilled workers to 67.9 % for plant and machine operators). In these two occupational classes, the proportion of persons with tertiary education was the lowest, at a maximum of 6.6 %.

Occupations requiring high skills are expected to give rise to more rewarding jobs both in terms of quality of the tasks undertaken and of their corresponding remuneration, and vice-versa. Hence, it is amongst managers, professionals technicians and associate professionals — most of whom are tertiary graduates — that the highest shares of employed people declaring a high level of job satisfaction were found (See article 2 on employment).

Relations between education and satisfaction

How are education and mental well-being connected?

Education, being likely to provide a different understanding of society and its challenges, but also as a gateway to a better income and social status, may lead to differences in individuals’ psychological well-being. This perception may be measured through various types of emotional aspects of subjective well-being, including feeling downhearted or depressed, down in the dumps, very nervous, or, on the contrary, happy[8].

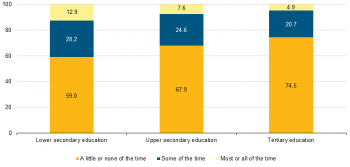

Education had a positive effect on psychological well-being

As shown in Figure 14, people with a low level of education appeared to be feeling downhearted or depressed more frequently than those in the other two groups. In the EU-28, on average, 12.9 % of them declared being in this state of mind most or all of the time, which was about two or three times more than holders of upper secondary and tertiary-level qualifications. Moreover, 59.0 % of them reported to be downhearted or depressed a little or none of the time, versus 67.9 % and 74.5 % in the other two groups. Similarly, the least educated had a higher propensity to feel down in the dumps, in rather comparable proportions as when reporting being depressed or downhearted.

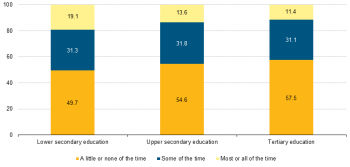

Being nervous gave rise to the same overall pattern, as depicted in Figure 15, but with less considerable divergences across the different levels of frequency of this emotion. Those with a lower level of education were almost three times as likely as the tertiary graduates to have felt downhearted or depressed most or all of the time in the last four weeks (12.9 % as opposed to 4.9 %), and almost twice as likely to have felt very nervous with the same frequency (19.4 % as compared with 11.4 %).

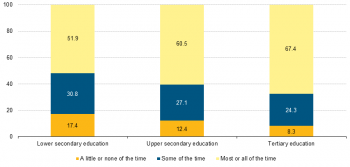

When it comes to assessing happiness, the least educated appeared once more as having the lowest level of happiness (Figure 16). About half of them (51.9 %) reported that they were feeling happy most or all of the time, against 60.5 % amongst people with upper secondary education and 67.4 % amongst tertiary graduates. On average, they were also much more prone to declare feeling happy only a little or none of the time.

Among the EU population with tertiary education, 67 % felt happy most or all of the time (in the last 4 weeks).

How are educational attainment and satisfaction with various aspects of life linked?

While educational attainment is an influencing factor of an individual’s mental well-being, it may also lead to distinct evaluations of some major aspects of everyday life, such as material living conditions, job, personal relationships, health and others. Ultimately, it may also affect overall life satisfaction and give rise to a different perception of its meaning.

Overall life satisfaction and meaning of life measure different things. Meaning of life is perceived as the psychological or ‘functioning’ approach to subjective well-being — such as purpose, sense of meaning or autonomy — while life satisfaction is intended to cover a broad, reflective appraisal of all areas relating to a person’s existence. The two items are regarded as key indicators for subjective well-being and are considered as reliable measures backed by international studies and guidelines[9] [10].

Education had a positive effect on almost all satisfaction items

An analysis of the impact of educational attainment reveals that the most educated almost systematically had a better assessment of their quality of life (Figure 17.a). The effect of education was strongest on the household’s satisfaction with the financial situation (the difference between the average of those with a high and those with a low level of education was around 1.3 points, on the 0–10 scale). The effect on overall life satisfaction was also quite significant (+ 0.9 mean rating for tertiary graduates). It was lowest on satisfaction with commuting time (+ 0.3). Time use was the only item where the least educated had a higher average degree of satisfaction than the most educated ones (0.2 point).

At country level, the gaps were quite small, below 1 point rating (on the 0–10 scale) in most cases. Central and eastern EU Member States registered the highest differences in rating between the least and the most educated people. In Croatia, the differential in favour of the most educated people reached 2.3 points in terms of satisfaction levels with the financial situation, the widest gap recorded by an EU Member State across all satisfaction items. The gap between the least and the most educated people was non-existent for both financial and overall life satisfaction in Sweden.

In some cases, the gap in rating favoured the least educated. Such was the case for satisfaction with accommodation in particular in Sweden and the United Kingdom; for job satisfaction in Sweden and Denmark; for satisfaction with commuting time in Denmark and Ireland; for satisfaction with personal relationships in Denmark and Sweden; and for satisfaction with green areas and environment in Greece.

Satisfaction with time use, which follows a specific pattern, being much less related to educational attainment and income, was systematically assessed as better by those having only completed lower education in France and Sweden (1 point difference at the expense of tertiary graduates).

While the analysis of educational attainment focused on the population aged 25–74, the analysis of the link between education and satisfaction was based on the total population of respondents (all current household members aged 16 and over) and did not reflect the influence of factors such as age, which are also influential (as could be seen in the other articles of this publication). Hence, in spite of being amongst the least educated people (as many did not yet complete the educational programmes they were attending), the youngest (16–24) assessed most life domains more positively than the total population, especially in the case of time use. Tertiary graduates also had more rewarding social relationships, felt more secure and assessed their health more positively (Figure 17.b).

This outcome could be explained by the fact that better education provides more opportunities for personal development and a better quality of life, by offering better opportunities to those who are most skilled, hence better paid jobs, and enabling a better understanding of the challenges which an individual has to face in a rapidly changing world. Beyond being an economic resource, for many, education may even be regarded as a value in itself.

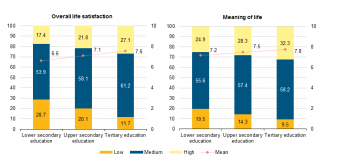

Ultimately, education had a positive influence on life satisfaction and its meaning

Figure 18 shows that education also favourably impacts the perception of life as a whole. Indeed, on average people with lower secondary education rated their overall life satisfaction at 6.6, which was 0.5 points less than amongst holders of upper secondary education and almost 1 point (0.9) less than amongst tertiary graduates. The shares of people having reported a low or high satisfaction with life were almost inverted across the two groups of least and most educated people.

Figure 18 also illustrates the link between education and the meaning of life, a ‘eudaimonic measure’ of subjective well-being[11]. It confirms the impact of education on subjective well-being, by revealing means ranging from 7.2 amongst people having completed lower secondary education, to 7.5 and 7.8 amongst the other two groups. While the gap across education groups was more limited, these ratings were higher than for overall life satisfaction. Nonetheless the patterns were quite similar.

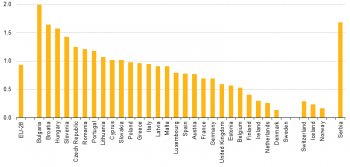

The most educated rated life satisfaction higher in most EU Member States

Figure 19 illustrates the gap in life satisfaction between people with a high and a low level of education at country level, revealing a divide between mostly northern and western EU Member States and a majority of the eastern and southern EU Member States. In Sweden the perception of individuals was identical across the three levels of educational attainments, at around 8.0 mean rating (the highest in the EU-28). The gap was negligible in Denmark (0.1 point rating) whose residents rated their life satisfaction at approximately 8.0 (just as in Sweden) whatever their education level.

In Bulgaria, the rating gap between the least (3.8 points) and the most educated people (5.8 points) was the largest as regards the 0–10 scale (for the whole population, mean life satisfaction reached 4.8, the lowest in the EU-28). Hungary and Croatia follow, with a rating gap equal to 1.6 points. These two EU Member States also recorded some of the lowest means for life satisfaction by total population (6.2 and 6.3, well below the EU-28 average of 7.1) . Estonia and Spain (and to a lesser extent Malta and Latvia) seemed to deviate from the pattern observed in most eastern or southern EU Member States, by displaying rating gaps below the EU-28 average (0.9 point).

In 2013, the gap in life satisfaction between people with a high and a low level of education was the widest in Bulgaria, followed by Hungary and Croatia.

The shares of tertiary graduates were only moderately associated with the proportion of highly satisfied residents

The relation between level of education and well-being is analysed in the cross-country picture (Figure 20). The shares of tertiary graduates appear to be in some cases associated with people reporting a high degree of overall life satisfaction. Hence, while registering some of the highest shares of tertiary graduates, over 32 % each, Denmark, Finland and Sweden also registered some of the most sizable proportions of residents highly satisfied with their life, ranging from 41.3 % in Denmark to 34.3 % in Sweden. In Austria on the other hand, which registered a quite similar share of highly satisfied residents (35.5 %), the share of tertiary graduates reached only 19.6 % (which was 7.1 percentage points below the EU average). Moreover, Ireland, the United Kingdom and Luxembourg, which recorded, along with Finland, the highest shares of tertiary graduates (above 38 %), reported comparatively less positively on life satisfaction (especially the Finnish at 38.9 %) with shares of highly satisfied residents varying between 29.4 % in Ireland and 24.8 % in Luxembourg.

At the other end of the scale, a group of EU Member States with similar shares of tertiary graduates, below 20 %, reported differently on life satisfaction: the residents of Italy, Portugal and Croatia were much less satisfied (below 15 % of high satisfaction) than their counterparts from Romania, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Malta (which reported shares of tertiary graduates varying between 19.8 % in the Czech Republic and 23.3 % in Slovakia).

As seen above, the Austrians assessed their life much more positively (35.5 %) with similar proportions of highly educated people (19.6 %) as in the previous group. Bulgaria was another special case: only 5.2 % of its residents appeared to be highly satisfied with their life while one fourth of them (24.2 %) had graduated from tertiary education. This negative perception was also visible in Cyprus and Estonia where high life satisfaction was only reported by about 12–13 % of residents while the share of tertiary graduates reaches about 37 %. In several other EU Member States, such as Latvia, France, Spain, Lithuania (and Belgium), the relatively high shares of people having graduated from higher education (close to 30 %) did not appear to translate in higher life satisfaction.

Data sources and availability

An ad-hoc module on subjective well-being was implemented in the EU-SILC 2013. This module contains subjective questions (e.g. How satisfied are you with your life these days?) which complement the mostly objective indicators from existing data collections and social surveys.

The "GDP and beyond" communication, the SSF Commission recommendations, the Sponsorship on measuring progress, and the Sofia memorandum all underlined the importance of collecting high quality data about people's quality of life and well-being and the central role that statistics on income and living conditions (SILC) have to play in this improved measurement. The collection of micro data related to well-being therefore is a key objective. In May 2010 both the Living Conditions Working Group and the Indicators Sub-Group of the Social Protection Committee supported Eurostat's proposal to collect micro data related to well-being within the 2013 module of SILC in order to better respond to this request.

For more information please visit: Eurostat - GDP and beyond - Quality of life

As a dimension of the Quality of Life framework, education refers to acquired expertise and skills, to the continued participation in lifelong learning activities and to aspects related to the access to education.

- Expertise and skills are measured through data on educational attainment of the population (provided by the EU-LFS), including an early school leavers indicator. These are complemented by measures on self-reported (knowledge of a foreign language and computer literacy) and assessed skills (currently available through the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies — PIAAC).

- Life-long learning covers the proportion of the population in further education and training (provided by the EU-LFS).

- Additional indicator related to opportunities for education is being developed. The indicator will cover participation of children aged 4 in early childhood education (ISCED 0+1).

The ISCED standard

The classification of educational activities is based on the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED). Data until 2013 are classified according to ISCED 1997 and data as from 2014 according to ISCED 2011. ISCED 1997 covered 6 categories at 1-digit level:

- Level 0 – Pre-primary education

- Level 1 – Primary education or first stage of basic education

- Level 2 – Lower secondary or second stage of basic education

- Level 3 – (Upper) secondary education

- Level 4 – Post-secondary non-tertiary education

- Level 5 – First stage of tertiary education

- Level 6 – Second stage of tertiary education.

ISCED 2011 cover 8 categories at 1-digit level:

- Level 0 – Less than primary education

- Level 1 – Primary education

- Level 2 – Lower secondary education

- Level 3 – Upper secondary education

- Level 4 – Post-secondary non-tertiary education

- Level 5 – Short-cycle tertiary education

- Level 6 – Bachelor’s or equivalent level

- Level 7 – Master’s or equivalent level

- Level 8 – Doctoral or equivalent level.

Data on educational attainment are presented for three aggregates – low, medium and high level of education:

- The aggregate ‘lower secondary education attainment’ refers to levels 0, 1 and 2 of the ISCED 2011. Data up to 2013 refer to ISCED 1997 levels 0, 1 and 2 but also include level 3C short (educational attainment from ISCED level 3 programmes of less than two years).

- The aggregate ‘upper secondary education attainment’ corresponds to ISCED 2011 levels 3 and 4. Data up to 2013 refer to ISCED 1997 levels 3C long, 3A, 3B and 4.

- The aggregate 'tertiary education attainment' covers ISCED 2011 levels 5, 6, 7 and 8. Data up to 2013 refer to ISCED 1997 levels 5 and 6

Context

Education affects the quality of life of individuals in many ways. People with limited skills and expertise tend to have worse job opportunities and worse economic prospects, while early school leavers face higher risks of social exclusion and are less likely to participate in civic life. In the same way as employment, education is at the very heart of European Union (EU) policies, in that the level of education of its residents can have a major impact on their employability, hence reducing their risk of poverty, by providing them the necessary skills and expertise to adapt in a rapidly changing labour market and society. By enhancing creativity, entrepreneurship and innovation, education can also contribute to job creation and growth. Moreover, beyond pragmatic considerations, education is one of the greatest values of society, since it allows for a better understanding of the world we live in.

EU policies related to education

Education plays a central role in the context of Europe 2020[12], the EU strategy for growth and jobs. Two headline targets of the overarching Europe 2020 strategy come from this field:

- at least 40 % of its 30-34–year-olds should be tertiary graduates; and

- early leaving from education and training should be less than 10 % by 2020.

Also, making lifelong learning and mobility a reality, as well as improving the quality and efficiency of education and training are objectives set in the strategic framework for European cooperation in education and training (ET 2020, Council conclusions of 12 May 2009). ET 2020 includes a benchmark of 95 % for the participation of children aged 4 in education.

Another important European strategy promotes multilingualism with a view to strengthening social cohesion, intercultural dialogue and European construction (Council Resolution of 21 November 2008).

See also

- All articles on living conditions and social protection

- Quality of life indicators (online publication)

Further Eurostat information

Main tables

- Income distribution and monetary poverty (t_ilc_ip)

- Monetary poverty (t_ilc_li)

- Monetary poverty for elderly people (t_ilc_pn)

- In-work poverty (t_ilc_iw)

- Distribution of income (t_ilc_di)

- Material deprivation (ilc_md)

- Material deprivation by dimension (t_ilc_mddd)

- Housing deprivation (t_ilc_mdho)

- Environment of the dwelling (t_ilc_mddw)

- Education attainment and outcomes of education (t_edat)

- E-skills of individuals and ICT competence in enterprises (t_isoc)

Database

- Income distribution and monetary poverty (ilc_ip)

- Monetary poverty (ilc_li)

- Monetary poverty for elderly people (ilc_pn)

- In-work poverty (ilc_iw)

- Distribution of income (ilc_di)

- EU-SILC ad hoc module (ilc_ahm)

- Education attainment level and outcome of education (edat)

- Lifelong learning - LFS data (trng_lfs)

- Adult Education Survey (trng_aes)

- E-skills of individuals and ICT competence in enterprises (isoc_sk)

Dedicated section

Methodology / Metadata

- Income and living conditions (ESMS metadata file — ilc_esms)

Source data for tables and figures and maps (MS Excel)

Notes

- ↑ European Commission, Education and training — Monitor report (2014), p. 30.

- ↑ European Commission, Education and training — Monitor report (2014), p. 30.

- ↑ European Commission (2014). Education and training – Monitor report 2014, p. 42, 46 and 49, 53.

- ↑ See flagship initiatives Digital Agenda for Europe and Agenda for new skills and jobs.

- ↑ European Commission, Education and training — Monitor report (2014), p. 49.

- ↑ European Commission, Education and training — Monitor report (2014), p. 8.

- ↑ European Commission, Europe 2020 — A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, COM(2010) 2020 final (2010).

- ↑ The data source used is the 2013 ad-hoc module on subjective well-being from the Eurostat EU-SILC survey, in which respondents are all current household members aged 16 and over who are currently working. The variables (PW050–090) are based on self-rated affects or emotions and aim at measuring psychological well-being. The variables refer to the respondent’s feeling; he/she should be invited to indicate to what extent he/she has felt this way during the past four weeks. ‘Being nervous’ should be understood as a status characterised by or showing emotional tension, restlessness, agitation, etc. Further references can be found in EHIS Guidelines or on the International quality of life assessment (Iqola) website.

- ↑ Life satisfaction (variable PW010) represents a report of how respondents evaluate or appraise their life taken as a whole. It is intended to represent a broad, reflective appraisal people make of their lives. The term life is intended here as all areas of a person’s life at a particular point in time (these days). The variable therefore refers to the respondents’ opinion/feeling about the degree of satisfaction with their lives. It focuses on how people are feeling ‘these days’ rather than specifying a longer or shorter time period. The intent is not to obtain the current emotional state of the respondent but for them to make a reflective judgement on their level of satisfaction. See E. Diener, Guidelines for National Indicators of Subjective Well-Being and Ill-Being.

- ↑ Meaning in life (variable PW020) is a multi-faceted construct that has been conceptualised in diverse ways. It refers broadly to the value and purpose of life, important life goals, and for some, spirituality. The respondents should be invited to think about what makes their lives and existence feel important and meaningful and then answer by rating life from ‘Not worthwhile at all’ (0 rating) to ‘Completely worthwhile’ (10). The term ‘worthwhile’ denotes meaning of purpose/beneficial. It is not related to any specific area of life, focuses rather on life in general.

- ↑ Etymologically, eudaimonia consists of the words ‘eu’ (good) and ‘daimōn’ (spirit). It is a central concept in Aristotelian ethics where it was used as the term for the highest human good. (See article 9 on overall life satisfaction)

- ↑ European Commission/Eurostat, Smarter, greener, more inclusive? Indicators to support the Europe 2020 strategy (2014), p. 94.