Archive:Europe 2020 indicators - education

Data extracted in August 2019.

No planned update.

This Statistics Explained article is outdated and has been archived - for recent information on Europe 2020 strategy see here.

Highlights

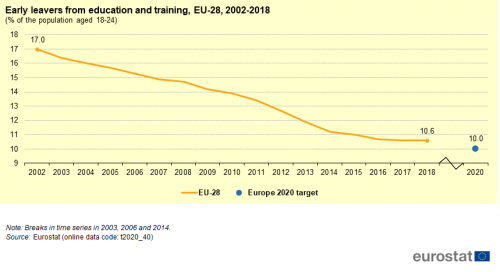

Early leaving from education and training has been falling continuously in the EU since 2002, for both men and women. The fall from 17.0 % in 2002 to 10.6 % in 2018 represents steady progress towards the Europe 2020 target of 10 %.

(% of the population aged 18–24)

Source: Eurostat online data code (t2020_40)

This article is part of a set of statistical articles on the Europe 2020 strategy. It provides recent findings on education in the European Union (EU).

Full article

General overview

The Europe 2020 strategy is the EU’s agenda for growth and jobs for the current decade. It emphasises smart, sustainable and inclusive growth as a way to strengthen the EU economy and prepare its structure for the challenges of the next decade.

Education is a key policy component of the Europe 2020 strategy. The EU’s educational targets are interlinked with the other Europe 2020 goals as higher educational attainment improves employability, which in turn reduces poverty. The tertiary education target is furthermore interrelated with the research and development (R&D) and innovation target as investment in the R&D sector is likely to raise the demand for highly skilled workers.

Europe 2020 strategy target on education

The Europe 2020 strategy sets out a target of reducing the rates of early leavers from education and training to less than 10 % and increasing the share of the population aged 30 to 34 having completed tertiary education to at least 40 % by 2020 [1].

Continuous decrease in early school leaving

The EU regards upper secondary education as the minimum desirable educational attainment level for EU citizens. The skills and competences gained at this level are considered essential for a successful entry into the labour market and as the foundation for adult learning. Therefore, the headline indicator ‘early leavers from education and training’ measures the share of the population aged 18 to 24 with at most lower secondary education and who were not involved in further education or training during the four weeks preceding the survey.

Figure 1 shows that the share of early leavers has fallen continuously from 17.0 % in 2002 to 10.6 % in 2018, albeit at a slower pace in recent years. The stagnation of this trend over the past three years, however, has pushed the EU slightly off its path towards the Europe 2020 target of 10 %.

Significant reductions can be observed in almost all Member States for both men and women, although overall more men leave education and training early than women [2].

(% of the population aged 18–24)

Source: Eurostat online data code (t2020_40)

Substantial decreases in ‘early leavers’ in southern European countries

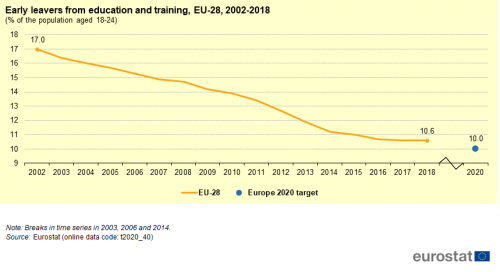

Reflecting different national circumstances, the overall EU target for early leavers from education and training has been transposed into national targets by all Member States except the United Kingdom. National targets range from 4 % for Croatia to 16 % for Italy. As shown in Figure 2, 13 Member States had already achieved their national targets in 2018.

Rates of early leaving vary widely across Member States. In 2018, the lowest proportion of early leavers was observed in some southern and eastern European countries (Croatia, Slovenia, Lithuania, Greece and Poland) with rates of less than 5 %. At the same time, some other southern countries, such as Spain (17.9 %), Malta (17.5 %) and Romania (16.4 %) reported the highest shares in the EU.

Southern European countries also experienced strong falls in early leaving between 2008 and 2018, especially Portugal (from 34.9 % to 11.8 %), Spain (from 31.7 % to 17.9 %) and Malta (from 27.2 % to 17.5 %). On the other hand, there are five Member States with higher shares in 2018 than in 2008 (Slovakia, Sweden, Czechia, Hungary and Romania). A total of 17 Member States were already below the overall EU target of 10 % in 2018.

Country of birth strongly influences the rate of early leaving across the EU (see Figure 3). People who live in a country different from the one where they were born are more likely to struggle to complete their education. Socioeconomic status underlies much of this difficulty, but issues associated with immigration such as language barriers and settling into a new environment are also at play, according to the Migration Policy Institute [3].

(% of the population aged 18–24)

Source: Eurostat online data code (t2020_40)

(% of the population aged 18–24)

Source: Eurostat online data code (edat_lfse_02)

Early school leaving leads to severe problems in the labour market

In general, low educational attainment — at most lower secondary education — influences other socioeconomic factors. The most important of these are employment, unemployment and the risk of poverty or social exclusion. Some of these relationships are also analysed in detail in other articles (see the articles on ‘Employment’ and ‘Poverty and social exclusion’).

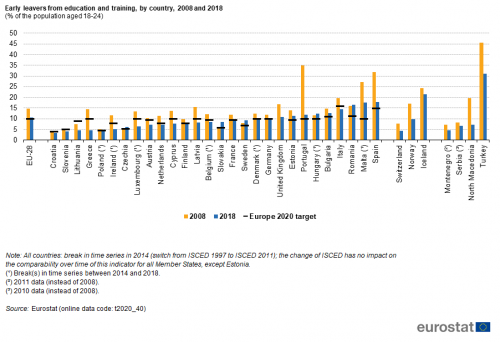

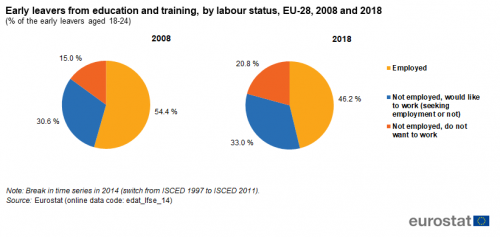

Early leavers from education and training face particularly severe problems in the labour market. As Figure 4 shows, 53.8 % of early leavers were either unemployed or inactive in 2018. The situation for early leavers has worsened over time: between 2008 and 2018, the share of 18- to 24-year-old early leavers who were not employed but who wanted to work grew from 30.6 % to 33.0 %. However, this increase has not been continuous — the situation has actually improved in recent years with the share falling from 37.4 % in 2016 to 33.0 % in 2018.

(% of the early leavers aged 18–24)

Source: Eurostat online data code (edat_lfse_14)

Increasing attainment at tertiary level

The Europe 2020 target for tertiary education was met in 2018

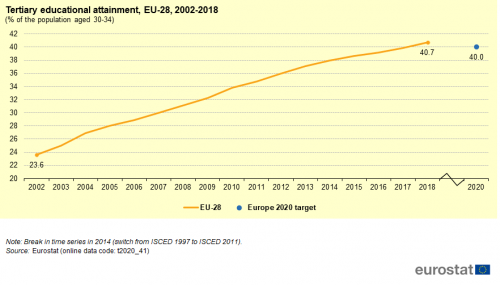

The second Europe 2020 education target — raising the share of the population aged 30 to 34 that have completed tertiary or equivalent education to at least 40 % — is monitored with the headline indicator on tertiary educational attainment of the same age group [4].

Figure 5 shows a steady and considerable growth in the share of 30- to 34-year-olds who have successfully completed a university degree or other tertiary-level education since 2002. The share of 40.7 % in 2018 implies a growth of 17.1 percentage points since 2002, and means that the Europe 2020 target has already been reached two years early.

There is a significantly widening gender gap among people with tertiary educational attainment across the EU. While in 2002 this share was almost similar for both sexes, the share of females with tertiary education has grown at almost twice the rate, resulting in a gender gap of 10.1 percentage points in 2018 [5].

(% of the population aged 30–34)

Source: Eurostat online data code (t2020_41)

All Member States have made significant progress in raising tertiary educational attainment

The increase in tertiary educational attainment levels across the EU is mirrored across all Member States. This to some extent reflects countries’ investment in higher education to meet the demand for a more skilled labour force. Another factor is the shift to shorter degree programmes following the implementation of Bologna [6] process reforms in some countries.

National targets for tertiary education range from 26 % for Italy to 66 % for Luxembourg. Germany’s target is slightly different from the overall EU target because it includes post-secondary, non-tertiary attainment (ISCED level 4). For France, the target definition refers to the 17- to 33-year age group while for Finland the target excludes former tertiary vocational education and training (VET).

Figure 6 shows that in 2018, 17 countries had already achieved their national targets. Croatia and Hungary were close at less than one percentage point from their national targets.

In 2018, levels of tertiary educational attainment varied by a factor of about 2.3 across Europe. Northern and central Europe had the highest share of population with tertiary education, with 19 countries exceeding the overall EU target of 40 %. The lowest levels could be observed in Romania (24.6 %) and Italy (27.8 %). At the same time, some eastern European countries experienced the strongest increases over the period 2008 to 2018. Changes were most pronounced in Slovakia and Czechia where the shares more than doubled.

Across other major world economies [7], tertiary attainment rates vary greatly, but all countries showed clear increases between 2008 and 2017. South Korea experienced the biggest rise, of 11.9 percentage points, reaching a tertiary educational attainment rate of 69.8 % for the age group 25 to 34 in 2017. At 39.0 %, the EU had a significantly lower rate than some other industrialised countries in this age group [8].

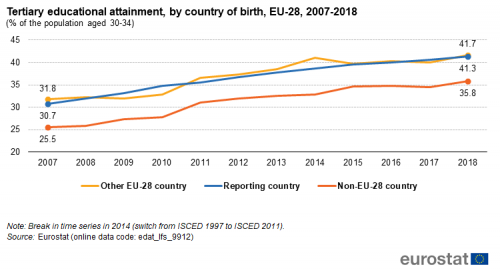

Figure 7 shows that the share of tertiary educational attainment has increased significantly, independently from the country of birth, between 2007 and 2018. However, people who were born in a non-EU-28 country have lower rates of tertiary attainment than people born in the EU.

(% of the population aged 30 to 34)

Source: Eurostat online data code (t2020_41)

(% of the population aged 30–34 )

Source: OECD and Eurostat online data code (edat_lfs_9912)

Data sources

Indicators presented in the article:

- Early leavers from education and training’ (t2020_40)

- Breakdown by broad group of country of birth (edat_lfse_02)

- Breakdown by labour status (edat_lfse_14)

- Tertiary educational attainment (t2020_41)

- Breakdown by country of birth (edat_lfs_9912)

Context

Education and training lie at the heart of the Europe 2020 strategy and are seen as key drivers for growth and jobs. The consequences of the economic crisis along with an ageing population, through their impact on economies, labour markets and society, are two important challenges that are changing the context in which education systems operate [9]. At the same time, education and training help boost productivity, innovation and competitiveness.

Nowadays upper secondary education is considered the minimum desirable educational attainment level for EU citizens. Young people who leave education and training prematurely lack crucial skills and run the risk of facing serious, persistent problems in the labour market and experiencing poverty and social exclusion. Those early leavers from education and training who do enter the labour market are more likely to be in precarious, low-paid jobs and to draw on welfare and other social programmes. They are also less likely to be ‘active citizens’ or engage in adult learning.

In addition, tertiary education, with its links to research and innovation, provides highly skilled human capital (see the article on ‘R&D and innovation’). A lack of these skills presents a severe obstacle to economic growth and employment in an era of rapid technological progress, intense global competition and labour market demand for ever-increasing levels of skill. The Europe 2020 strategy, through its ‘smart growth’ priority, aims to tackle early school leaving and to raise tertiary education levels.

The EU’s educational targets are interlinked with the other Europe 2020 goals as higher educational attainment improves employability, which in turn reduces poverty. The tertiary education target is furthermore interrelated with the research and development (R&D) and innovation target as investment in the R&D sector is likely to raise the demand for highly skilled workers.

Direct access to

- Towards robust quality management for European Statistics - Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council COM(2011) 211 final

- Regulation (EC) No 223/2009 of 11 March 2009 on European statistics

- Summaries of EU Legislation: European statistics: how the European Statistical System works

Notes

- ↑ European Commission (2014), Taking stock of the Europe 2020 strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, COM(2014) 130 final.]

- ↑ For more detailed analysis of the gender gap for early leavers from education and training see Eurostat (2019), Sustainable development in the European Union. Monitoring report on progress towards the SDGs in an EU context — 2019 edition, chapter on SDG 4 ‘Quality education’.

- ↑ Nouwen, Ward, Noel Clycq, and Daniela Ulicna (2015), Reducing the risk that youth with a migrant background in Europe will leave school early, Migration Policy Institute, Brussels. Europe and SIRIUS Policy Network on the education of children and youngsters with a migrant background.

- ↑ For more detailed analysis of the gender gap for tertiary educational attainment see Eurostat (2019), Sustainable development in the European Union. Monitoring report on progress towards the SDGs in an EU context — 2019 edition, chapter on SDG 4 ‘Quality education’.

- ↑ Educational attainment is defined according to the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED). Tertiary educational attainment refers to ISCED 2011 level 5–8 (for data as from 2014) and to ISCED 1997 level 5–6 (for data up to 2013).

- ↑ The Bologna process put in motion a series of reforms to make European higher education more compatible, comparable, competitive and attractive for students. Its main objectives were: the introduction of a three-cycle degree system (bachelor, master and doctorate); quality assurance; and recognition of qualifications and periods of study (source: Education and training statistics introduced).

- ↑ The data refers to the 25–34 age group, because the OECD database does not include the 30–34 age group that is used for the Europe 2020 target. Source: OECD (Population with tertiary education).

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (edat_lfse_03)).

- ↑ For further information on the impact of demographic ageing on the labour force, see the article on `Employment`.