Archive:Tourism employment

- Data from September 2008, most recent data: Further Eurostat information, Main tables and Database.

The importance of the tourism industry for economic, social and cultural development in Europe and the role of tourism as a driver of development and socioeconomic integration are generally acknowledged.

This article takes a look at the contribution made by the tourism industry to the labour market in the European Union (EU), focusing on the pattern of employment in the tourist accommodation sector.

Main statistical findings

Overall view

On average, 1.1% of persons employed in the EU work in the tourist accommodation sector.

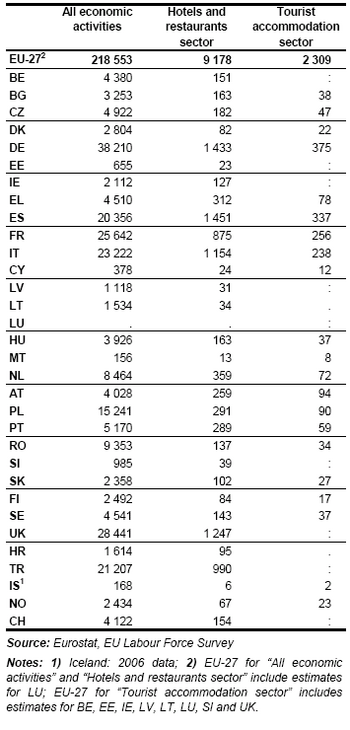

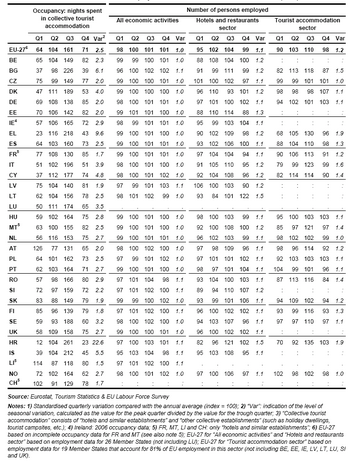

In 2007, more than 9 million persons were employed in the hotels, restaurants and catering (horeca) sector in the EU (see Table 1); this equals 4.2% of all persons employed. The highest number of jobs in this sector was observed in Spain (1.45 million), followed by Germany (1.43 million). However, when taking into account the size of the labour market, the largest shares employed in the horeca sector were found in Malta (8.3%), Spain (7.1%), Greece (6.9%), Austria (6.4%) and Cyprus (6.3%).

About one out of every four persons employed in the horeca sector works in an enterprise providing tourist accommodation (hotels and similar accommodation, campsites, etc.), giving a total of 2.3 million employed in 2007. At the height of the tourist season, i.e. in the third quarter of the year, the number of persons employed climbs by an additional 10 percent to an estimated 2.5 million (see below). In relative terms, this means that 1.1% of all the employed in the European Union work in the tourist accommodation sector. The Member States showing the highest share of employment in tourist accommodation were Malta (5.3%), Cyprus (3.2%) and Austria (2.3%). Not surprisingly, these are also the top three Member States in terms of tourism intensity, i.e. the number of nights in collective tourist accommodation divided by the number of inhabitants.

The sections which follow take a closer look at the pattern of employment in the tourist accommodation sector, compared with the horeca sector and the labour market as a whole.

By gender

The share of female employment in the tourist accommodation sector is high at 60%.

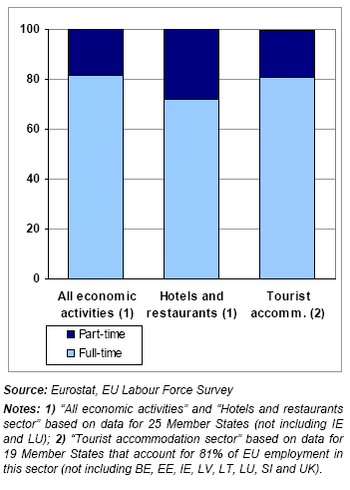

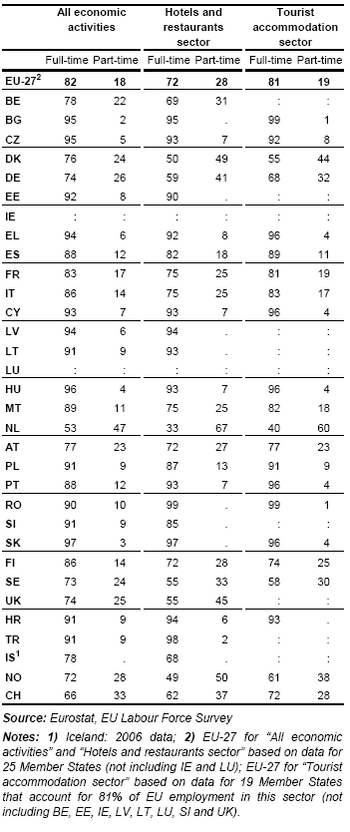

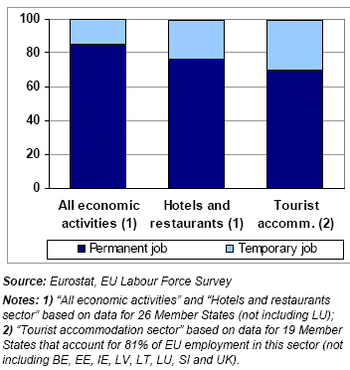

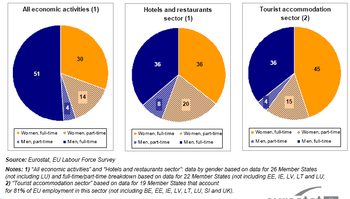

Figure 2 shows that the share of full-time employment in the tourist accommodation sector is not much different from the share in the EU-27 economy as a whole. About four out of every five persons are employed on a full-time basis. Looking at the hotels and restaurants sector as a whole, this is the case for only 72% of the persons employed (or 69% when excluding the tourist accommodation subsector). Only in the Czech Republic does part-time work tend to be slightly more common in tourist accommodation (8%) than in the horeca sector as a whole (7%).

Looking at the country data (see Table 2), big differences can be seen, ranging from almost no parttime employment in the tourist accommodation sector in Bulgaria or Romania to a rate of 60% in the Netherlands. In general, the figures for this sector reflect the full-time/part-time breakdown in the economy as a whole. Countries with a high share of part-time employment in short-stay accommodation, such as the Netherlands, Denmark (44%), Norway (38%), Germany (32%) or Sweden (30%), also have around 25% or more part-time workers in the whole labour market, compared with the EU average of 18%.

The tourist accommodation sector is a major employer of women (see Table 3 and Figure 1). On average, 60% of the EU labour force in this sector consists of female workers, who make up only 45% of the persons employed in all economic activities in the EU. In terms of creating job opportunities for women, the accommodation sector scores even better than the hotels and restaurants sector as a whole – where female employment stands at 56%.

As Table 3 shows, the differences across the European Union are relatively small, although slightly more pronounced than for the economy as a whole, where in nearly every country the share of female employment deviates from the EU average of 45% by no more than a few percentage points. Among the countries for which data are available, more than two out of every three persons employed in the tourist accommodation sector are female in Romania (72%), Norway (71%), Poland (70%), Finland (70%) and Germany (69%). Malta (38%) and Italy (49%) are the only countries where women do not take the majority of the jobs in the tourist accommodation sector. But, together with Greece, these two countries also have the lowest female participation rate in the economy as a whole.

The right-hand side of Table 3 combines the analysis by gender with the full-time/part-time breakdown (see also Graph 1). The proportion of women working full-time is much higher in the accommodation sector (75%) than in the rest of the economy (68%) or, more specifically, than in the hotels and restaurants sector as a whole (64%). Among men working in this sector, 90% have a fulltime contract, which is slightly less than the overall average for men (92%).

Only in the Nordic countries – Denmark (50% versus 36%), Sweden (51% v. 42%) and Finland (27% v. 19%) – are significantly more women working parttime in the tourist accommodation sector than in the economy as a whole. On the other hand, a significantly higher proportion of women are working full-time than in the economy in general in Austria (69% versus 59%), Portugal (96% v. 83%) and Switzerland (59% v. 41%).

The lowest rate of full-time employment in the EU can be observed in the Netherlands, for both male (59%) and female (28%) workers, but this Member State also registers the lowest overall average rate across the EU for both men and women.

The shaded/patterned sections of the pie charts in Graph 1 show the share of part-time employment. In both the tourist accommodation sector and in the labour market as a whole, slighly less than 20% of persons employed works on a parttime basis, 19% and 18% respectively. In both cases, women account for around 80% of these part-time jobs. Out of 100 persons employed in the EU, 4 are part-time working men while 14 are part-time working women. For the tourist accommodation sector this is 4 and 15 respectively.

The situation with full-time employment is more pronounced. Women occupy 56% of full-time jobs in the accommodation sector. Indeed, out of 100 persons employed in this sector in the EU, on average 81 work full-time, of which 45 are women and 36 are men. On average in the economy womenaccount for only 37% of full-time employment.

By age

43% of those employed in the tourist accommodation sector are under 35 years old.

Both the hotels and restaurants sector as a whole and the tourist accommodation sector offer job opportunities to a young workforce. Indeed, with 48% of persons employed in hotels and restaurants and 43% in the tourist accommodation sector younger than 35 years, both have a much younger age profile than the rest of the European Union labour market, where only about one in three of those employed is under 35 (see Figure 3).

This observation at EU level also applies to most of the Member States for which data on the age profile of employment in tourist accommodation are available (see Table 4). In most of these countries, the share of the two youngest age groups taken together lies 10 or more percentage points above their average share in employment in the economy as a whole. Under-35s make up more than half of the employees in the tourist accommodation sector in Slovakia (58%), the Netherlands (56%), Sweden (56%) and Norway (56%). In all four countries, this share exceeds the average for the whole economy by around 20 percentage points. Cyprus is the only Member State where the age profile of employees in tourist accommodation is less young, with under-35s taking just 28% of the jobs in the tourist accommodation and 33% in the horeca sectors, whereas their share in the economy of Cyprus as a whole stands at 37%. Only in Greece and Spain, two countries with a big tourism industry, does the age profile in the accommodation sector appear to be not significantly different from the age profile in all economic activities taken together.

At the other end of the age distribution, employment opportunities for persons aged 55 or more tend to be more limited in tourist accommodation (11%) than in the labour market (14%) overall. However, it must be underlined that reliable data are available for only a few countries, partly due to the low probability of including older persons employed in this sector in the sample for the survey used to collect the data.

By education level

More than one third of tourism accommodation employees has lower level of education.

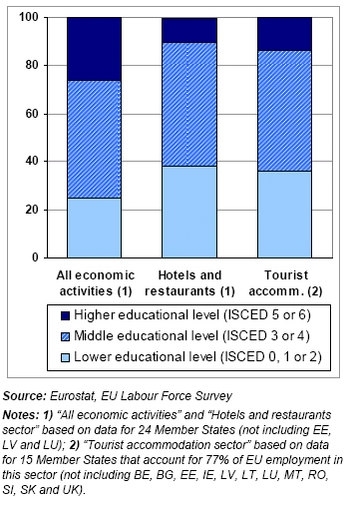

The data in the previous sections revealed that tourist accommodation in particular employs younger and female workers. A third socio-demographic group strongly represented in this sector are persons with a lower level of education, i.e. persons who completed lower secondary education at most. Figure 4 on page 8 and Table 5 on the next page show that 36% of employees in the tourist accommodation sector did not complete upper secondary education, compared with a general labour market average of 25%.

For all countries where data on employment broken down by educational level are available, the conclusion that the tourist accommodation sector employs relatively more persons with a lower level of education holds true. The biggest deviations from the average for the economy can be observed in Switzerland, where the share of lower educated persons in tourist accommodation is more than double their share in the whole labour market (36% versus 16%). Other countries where – compared with the entire economy – this sector offers jobs especially to less educated persons are Germany, Sweden, Norway and Denmark. Portugal (71%), Cyprus (24%) and Hungary (14%) are the only countries where there seems to be no noticeable difference (Portugal being the country with the highest share of employees with a low level of education in the European Union).

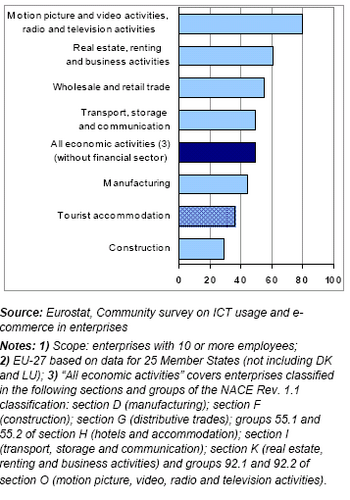

These findings are in line with the statistics on ICT use in enterprises (see Figure 5), which indicate that the tourist accommodation sector does not require a high level of e-skills from most staff. Instead, only 36% of the employees in this sector use computers in their daily work, compared with almost one out of every two employees (49%) when considering all economic activities. Among the branches covered by the Community survey on ICT usage and e-commerce in enterprises, only the construction sector has a lower penetration rate for ICT at the place of work than the hotel and accommodation sector.

By job status

A high share of temporary jobs and limited average stay with the same employer.

Graph 2 showed that the accommodation sector does not differ significantly from the rest of the economy in terms of full-time/part-time breakdown. However, considering the duration of the jobs and the average stay with the same employer, the sector appears to offer less stable jobs than the rest of the labour market.

The proportion of those having a temporary job rather than a permanent job (see Graph 6) is more than twice as high in the tourist accommodation sector (where 30% of the jobs are temporary) than in the economy as a whole (14%). In all the countries for which data on the duration of jobs are available, the accommodation sector performs relatively poorly (see Table 6). The largest discrepancies between this sector and the economy as a whole can be observed in Greece (59% permanent jobs v. 89% in the whole economy), Italy, Sweden and Bulgaria. The more limited availability of permanent jobs can be linked to the seasonal nature of tourism. Indeed, Greece, Italy, Bulgaria and Malta also appear to have the largest variation in number of persons employed between the peak and the trough quarters (see Table 9 on page 11). The discrepancy in terms of share of permanent jobs between the tourist accommodation sector and the economy as a whole is particularly small – not more than 3 percentage points – in Hungary, Finland, Denmark and Spain.

The lowest shares of permanent jobs in the tourist accommodation sector can be found in Poland (58%), Greece (59%) and Sweden (61%). In the case of Poland, however, this is not exceptional, as this is also the Member State with the lowest proportion of permanent jobs in the economy as a whole (72%).

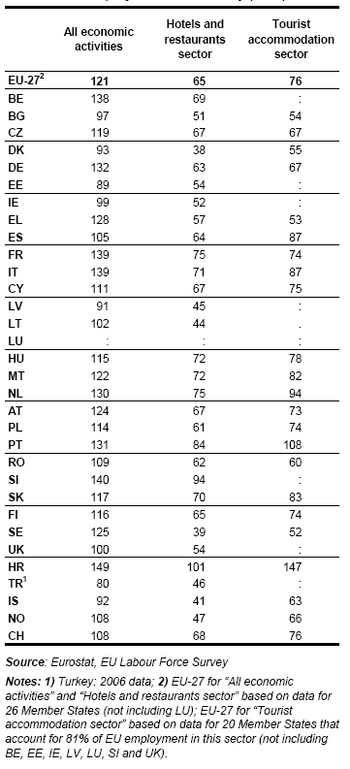

Another indicator of stability of employment is the average stay with the same employer. Table 7 shows that staff turnover is much higher in the accommodation sector – with an average stay with the same employer of slightly over 6 years (76 months) – than in all economic activities taken together (121 months, in other words more than 10 years). Comparing the accommodation sector with the rest of the economy at the level of the Member States, the average stay is less than half as long in Greece and Sweden. On the other hand, the discrepancy seems to be smallest in Portugal and Spain.

Seasonal variation

The tourist accommodation sector has a strong seasonal component.

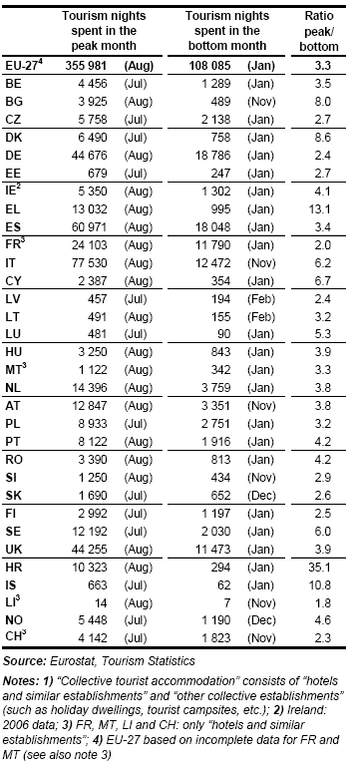

Tourism activity varies strongly in the course of the year. In every Member State, occupancy in collective accommodation (expressed as number of nights spent by tourists) is at least twice as high in the peak tourism month as in the quietest month (see Table 8). Logically, the countries with a short tourist season1 have the highest seasonal variation in nights spent. In Greece and Croatia, the number of nights spent in collective accommodation is respectively 13 and 35 times higher in August than in the low season in January.

The quarterly data in Table 9 show that the number of tourism nights is 2.5 times higher in the third quarter (the peak quarter) of the year than in the first quarter (the trough quarter). With a ratio of “only” 1.2, employment in this sector tends to be far less affected by seasonal influences (see also Figure 7). On average, the seasonal variation is only half as pronounced in the hotels and restaurants sector as a whole as in the tourist accommodation subsector. In only four countries (the Czech Republic, Denmark, the Netherlands and Norway) employment in the latter subsector seems to be less volatile over the year than in the horeca sector. In the economy as a whole, seasonal fluctuation is relatively limited – but this robust aggregate can, of course, hide strong seasonal variations in certain branches of the economy. Within the tourist accommodation sector, the highest seasonal fluctuations in employment are observed in Greece and Croatia (see Table 9). In both these countries, the level of employment in the peak quarter of the year is nearly double the level in the trough quarter and 30% to 35% higher than the annual average. At the other end of the spectrum, there is no significant seasonal variation in employment in Denmark, the Netherlands and Norway, although the number of nights spent by tourists is two to three times higher in the peak season than in the low season.

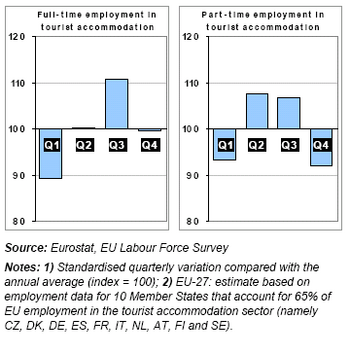

Based on data for ten Member States (accounting for 65% of employment in the tourist accommodation sector in the EU), Figure 8 shows the seasonal variation in employment separately for full-time and part-time jobs. The two types of employment contract tend to have a different seasonal pattern. While both are relatively low in the first quarter, part-time employment seems to be the main contributor to the seasonal needs in the second quarter. In the third quarter, full-time jobs appear to fill the additional needs on the tourist accommodation labour market (although it is not clear from the data whether these are additional full-time posts or an increase in weekly working hours to bring existing part-time posts up to full-time level).

By region

Regions with high tourist activity tend to have lower unemployment rates.

Tourist activity can have a negative impact on the quality of life of the local population in highly touristic areas. However, the influx of tourists can also catalyse the local economy, including the labour market.

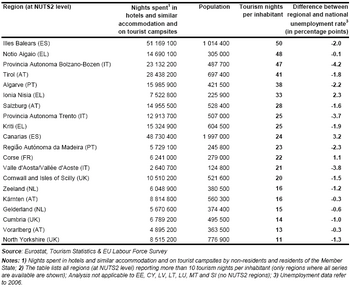

Table 10 lists the top regions (at NUTS 2 level) in the European Union in terms of number of nights spent by tourists per capita of the local population and takes a look at the unemployment rates in these regions. In order to take into account structural differences across the EU, the regional unemployment rate is compared with the unemployment rate at national level.

Although tourist activity will, of course, not be the only factor affecting the unemployment figures, Table 10 indicates that in all but three of the 20 most popular tourist regions listed, the unemployment rate lies below the national average. Two of the three regions where this does not hold true, namely the Canary Islands and Corsica, are island regions relatively remote from the mainland.

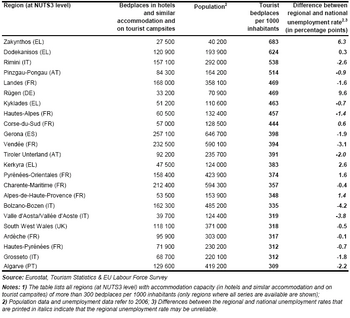

The Community statistics on tourism provide no data on occupancy of collective accommodation below the NUTS2 regional breakdown. However, at a more detailed regional level the number of bedplaces in tourist accommodation in comparison with the local population figures can be used as a proxy for the intensity of tourist activity in the region – assuming the capacity eventually accommodates tourist visitors. Table 11 on the next page shows that in most of these tourist areas the unemployment rate is lower than the national rate. Two of the most significant exceptions to this finding are the Greek islands Zakynthos (Zante) and Kerkyra (Corfu), both part of the Ionian Islands (see also Table 10). As shown above, Greece tends to have a highly seasonal tourism industry. This seasonal component possibly distorts the comparison as the unemployment figures are an annual average. In Rügen, Germany’s number one region in terms of tourism intensity, the unemployment rate is nearly 10 percentage points higher than the German average. In this specific case, the comparison is affected by the fact that Rügen is in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, the Bundesland with the highest unemployment rate.

Total employment

Tourism industry in EU occupies about 13 million persons.

The analysis in this paper mainly focused on the tourist accommodation sector, not on the entire tourism industry. In general, the breakdown into economic activities used in official statistics does not single out the tourism sector as a whole. In particular, apart from a few core tourist activities such as tourist accommodation or the activities of tour operators and travel agencies, most tourist activities can be filed under sectors of the economy of a broader nature. For instance, restaurants can cater for both tourists and locals or transport companies can provide services to tourists but can equally well run freight or commuter operations. To overcome this measurement problem, the European Union, together with international organisations active in the field of tourism statistics (the UNWTO, UNSD and OECD), has been fostering development of a framework that will allow accurate measurement of the tourism industry and comparison with other branches of the economy. Taking the concepts, definitions and aggregates of the System of National Accounts as a starting point, this statistical instrument called “Tourism satellite accounts” (TSA) should allow valid comparisons with other industries and also between countries or groups of countries. Part of these TSA cover employment in the tourism industry. Unlike the analysis in this paper, the TSA figures are not limited to the tourist accommodation sector, but also include tourism-related activities of other branches, such as the food and beverage serving industry, passenger transport or culture, sports and recreation.

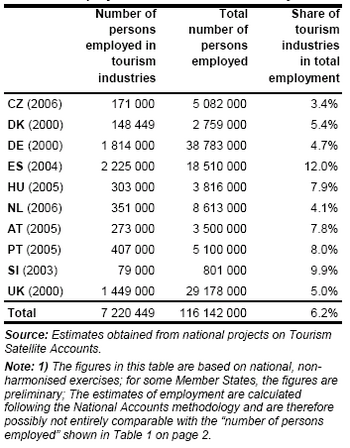

Currently, national, non-harmonised data are available for a handful of Member States. These estimates for 10 Member States are shown in Table 12. The contribution made by the tourism industry to total employment ranges from 3.4% in the Czech Republic to nearly 10% in Slovenia. In Spain the tourism industry accounts for almost one out of every eight jobs (12.0%) in the economy.

Based on the aggregate data for these 10 Member States, the share of the tourist industry in total employment appears to be around 6.2%. According to Table 1, employment in the accommodation sector accounts for around 1.1% of the labour market, or approximately 2.3 million jobs. From the TSA estimates, total employment in the tourist industry can be estimated to be five to six times higher, with somewhere between 12 and 14 million employed in the EU. Once again, it must be stressed that these preliminary figures are based on non-harmonised national data from only 10 Member States.

Data sources and availability

Data symbols

- “:”: no data available;

- “.”: unreliable figures that cannot be published;

Classifications

- The economic activities are classified in accordance with

NACE Rev.1.1, the statistical classification of economic activities. “Hotels and restaurants” correspond to division 55 of NACE Rev.1.1, whereas the “Tourist accommodation sector” covers only two classes of this division, namely 55.1 (hotels) and 55.2 (other short-stay accommodation).

Data sources

The data used in this article were generally collected by the national statistical institutes of the EU Member States, under Council Directive 95/57/EC of 23 November 1995 on the collection of statistical information in the field of tourism and under Council Regulation (EC) No 577/98 of 9 March 1998 on the organisation of a labour force sample survey in the Community. However, the data on employment in the tourist accommodation sector were provided to Eurostat on a voluntary basis, outside the legal framework.

Context

The tourist accommodation sector accounts for more than 25% of employment in the hotels, restaurants and catering (horeca) sector and for slightly over 1% of the entire labour market in the EU. • With a relatively high share of female workers (60%) and of workers with low formal educational qualifications (36%), tourist accommodation is a source of jobs for certain at-risk groups on the European labour market. Nevertheless, the jobs tend to be less stable. • The tourism industry is strongly affected by seasonal influences, leading to – on average across the EU – 10% more employment in the summer season. • Regions attracting large numbers of tourists very often have an unemployment rate below the national average.

Main definitions

Employed persons means persons aged 15 and over who during the reference week performed work, even for just one hour per week, for pay, profit or family gain or were not at work but had a job or business from which they were temporarily absent because of, e.g., illness, holidays, industrial dispute and education or training. Tourism means the activities of persons travelling to and staying in places outside their usual environment for not more than one consecutive year for leisure, business and other purposes.

Technical notes

- Labour force survey (LFS) data for Luxembourg are not used

because the Luxembourg labour market is too strongly affected by commuters from Belgium, Germany and France.

- Annual estimates for employment data are calculated by

taking the arithmetic average of the four quarters (except for Switzerland: second quarter used as annual estimate).

- Due to rounding, the percentages in the tables do not always

add up to exactly 100%.

Further Eurostat information

Publications

Main tables

Database

- Tourism, see:

- Employment in the tourism sector (Source: Labour Force Survey 'LFS')

Dedicated section

Other information

- Council Directive 95/57/EC on the collection of statistical information in the field of tourism

- Council Directive 2006/110/EC adapting Directives 95/57/EC and 2001/109/EC in the field of statistics, by reason of the accession of Bulgaria and Romania