SDG 10 - Reduced inequalities

Reduce inequality within and among countries

Data extracted in April 2024.

Planned article update: June 2025.

Highlights

This article is a part of a set of statistical articles, which are based on the Eurostat publication ’Sustainable development in the European Union — Monitoring report on progress towards the SDGs in an EU context — 2024 edition’. This report is the eighth edition of Eurostat’s series of monitoring reports on sustainable development, which provide a quantitative assessment of progress of the EU towards the SDGs in an EU context.

SDG 10 addresses inequalities within and among countries. It calls for nations to reduce inequalities in income as well as those based on age, sex, disability, race, ethnicity, origin, religion, or economic or other status within a country. The goal also addresses inequalities among countries and calls for support for safe migration and mobility of people.

Full article

Reduced inequalities in the EU: overview and key trends

It is widely agreed that economic prosperity alone will not achieve social progress. High levels of inequality risk leaving much human potential unrealised, damage social cohesion, hinder economic activity and undermine democratic participation. Leaving no one behind is thus a crucial part of achieving the SDGs. Monitoring SDG 10 in an EU context thus focuses on inequalities within countries, inequalities between countries, and migration and social inclusion. The EU has made significant strides in addressing income inequalities within countries over the five-year period assessed. Additionally, the trends in economic disparities between EU countries show a long-term convergence of Member States in terms of GDP and income. The picture is also quite positive for the area of migration and social inclusion of people with a migrant background, where the EU has made progress in reducing differences in social and labour market inclusion between home-country nationals and non-EU citizens.

Inequalities within countries

A high level of inequality can harm society in many ways. It can hamper social cohesion, result in lost opportunities for many, hinder economic activity, reduce social trust in institutions, lead to disproportionate exposure to adverse environmental impacts such as climate change and pollution, and undermine democratic participation [1]. Technological innovation and financial globalisation are some of the many factors driving inequality within countries by favouring people with specific skills or accumulated wealth [2]. Similarly, the transition to a climate-neutral society will have to be managed well to prevent rising inequality.

The income gap between high-income and low-income households in the EU has narrowed over the past few years

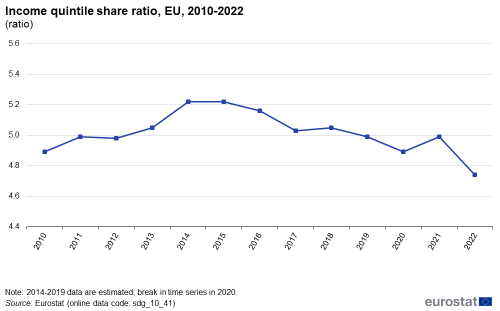

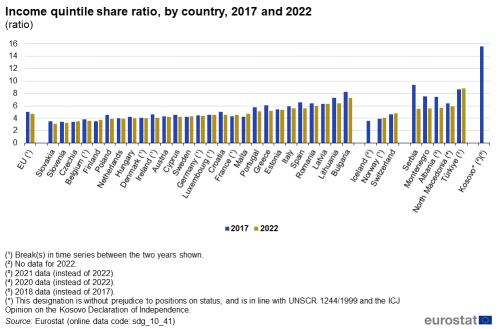

Analysing income distribution is one of the ways inequality within EU countries can be measured. The income quintile share ratio compares the income received by the 20 % of the population who have the highest equivalised disposable income with the income of the 20 % with the lowest equivalised disposable income. The higher this ratio, the bigger the income inequality between the bottom and the top ends of the income distribution. In the EU, this ratio had been decreasing in recent years, falling from 5.22 in the income year 2013 to 4.89 in the income year 2019 [3]. After a reversal of this trend in the income year 2020 when the ratio rose to 4.99 owing to the impact of COVID-19, the decline resumed in the income year 2021 with the ratio falling to 4.74. This means that the income of the richest 20 % of the EU households was almost five times as much as the poorest 20 %.

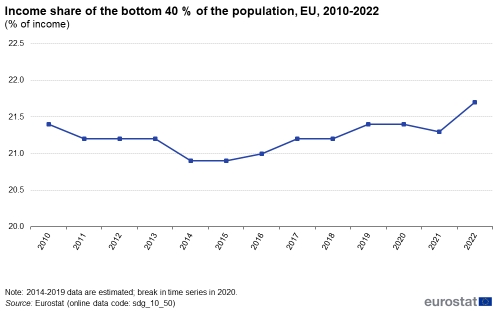

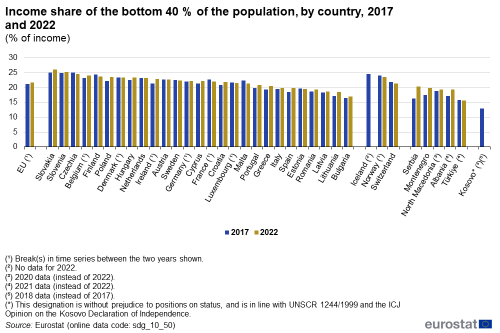

Reflecting the trend in the income quintile share ratio, the income share of the bottom 40 % of the population in the total equivalised disposable income had been increasing between the income years 2013 and 2018, followed by a stagnation and a slight decline in the next two years. However, this has also been a temporary reversal, as the income year 2021 saw a marked increase of this share to 21.7 %, representing a 0.4 percentage point improvement relative to the income year 2020. In addition to the significant improvements in the short term, the long-term trend shows an overall moderate progress in reducing the gap between the rich and the poor in the EU over the 12-year period assessed. It needs to be noted that recent trends in the two income inequality indicators analysed in this report are affected by methodological changes in the data collection from 2020 (referring to the income year 2019) onwards in a few Member States [4].

Economic inequality affects children’s long-term opportunities

Inequality is also of particular concern regarding the long-term outcomes and opportunities for children. It puts those affected at a disadvantage from the start in areas with long-lasting consequences, such as physical and mental health and education, thus undermining their development and human potential. To evaluate these disadvantages, indicators on several dimensions of childhood inequality of opportunity, such as income [5] and education [6], have been developed. Circumstances outside individual control, particularly parental background, lead to unequal outcomes in labour and disposable income. The contribution of parental background amounts to around three-quarters of the overall inequality of opportunity [7].

Moreover, there are wide variations between EU Member States regarding the childcare gap, which refers to a period in which families with young children are unable to benefit from childcare leave or a guaranteed place in early childhood care. While some Member States experience no childcare gap (for example, Denmark and Slovenia), others offer a relatively short period of childcare leave and guarantee a place in early childhood care only relatively late in the child’s life, at around five years of age (for example, the Netherlands and Ireland). Additionally, affordability of childcare remains an issue, especially for parents with multiple children and who are from low-income households [8]. Despite the observed positive benefits of early childhood education and care (ECEC) among children from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds, children from these backgrounds are less likely to participate in ECEC, particularly children under three years of age who are at risk of poverty and social exclusion, whose parents do not hold tertiary qualifications, and who live in large families [9].

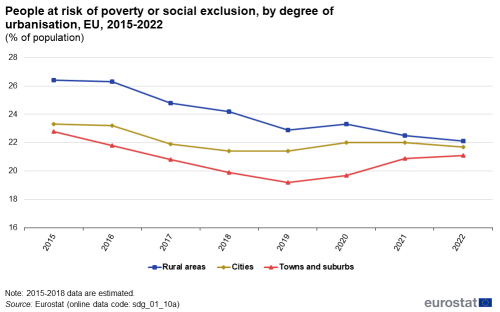

The poverty gap and the at-risk-of-poverty-or-social-exclusion gap between urban and rural areas have both narrowed in recent years

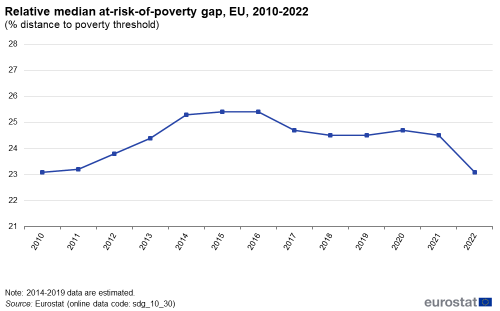

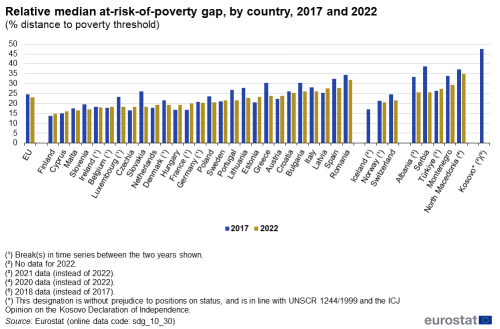

Inequality and poverty are closely interrelated. The poverty gap, defined as the distance between the median (equivalised disposable) income of people at risk of poverty and the poverty threshold (set at 60 % of the national median equivalised disposable income after social transfers) , has decreased since 2017, showing significant progress in the short run. In 2022, this gap narrowed by 1.4 percentage points relative to 2021 and amounted to 23.1 % in the EU. This means the median income of those below the poverty threshold was 23.1 % lower than the poverty threshold itself. This is a 1.6 percentage point narrowing of the gap since 2017, representing a significant short-term improvement in the ‘depth’ of monetary poverty in the EU. The long-term trend is characterised by an increase in the gap between 2010 and 2016, followed by a decrease that resulted in the poverty gap in 2022 falling back to the levels seen in 2010.

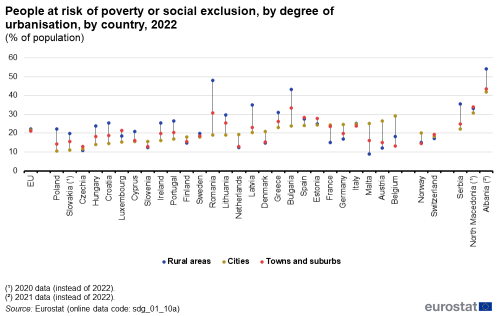

In 2022, 21.6 % of the EU population were at risk of poverty or social exclusion [10]. However, this rate differs between cities and rural areas. In the same year, the urban–rural gap in the at-risk-of-poverty-or-social-exclusion rate amounted to 0.4 percentage points, with 21.7 % of people living in cities being in this situation, compared with 22.1 % of people in rural areas. This represents a 0.1 percentage point decrease in the gap compared with 2021. The lowest share of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion was observed in towns and suburbs, with 21.1 % of people at risk in 2022.

The gap in the risk of poverty or social exclusion rate between cities and rural areas at EU level has thus significantly narrowed compared with 2017, when it was 2.9 percentage points. This development is the result of a stronger improvement in rural areas, where the share of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion has fallen by 2.7 percentage points since 2017. In contrast, the rate in cities has decreased by only 0.2 percentage points over the same time span.

However, the overall EU figure masks the full scope of the broad variations in gaps among Member States. Rural poverty remains extremely high in some European countries, such as Bulgaria and Romania, where 43.1 % and 47.9 % of the rural population were at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2022. This amounted to an urban-rural gap of 19.4 and 29.0 percentage points in these two countries, respectively. However, while rural areas generally tend to be at a higher risk of poverty due to out-migration and limited access to services, infrastructure, labour markets and educational opportunities [11], this is not the case in all Member States. Countries such as Malta, Austria, France and Belgium are reporting much higher poverty rates in cities than in rural areas.

There also exist large regional variations within the Member States, with more than 30 % of the population in numerous regions in Spain, Italy, Greece, Romania and Bulgaria being at risk of poverty [12]. Specifically, certain minorities such as Roma are at a much higher risk of monetary poverty. As of 2021, 80 % of Roma were at risk of monetary poverty, with their situation remaining unchanged since 2016. Moreover, 48 % of Roma were living in severe material deprivation in 2021, a reduction of 14 percentage points compared with 2016. Roma children under the age of 18 are particularly affected by poverty, with 83 % of those being at risk of poverty and 54 % living in households with severe material deprivation in 2021. This further adds to the vulnerability of the Roma population [13].

The gap between high-income and low-income population groups extends to their carbon footprint

In recent years, research has increasingly pointed to the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions gap between the high-income and low-income population groups. This emissions gap highlights that the poorer sections of the society contribute less to the climate crisis. Research has shown that reaching the EU’s 2030 target to reduce GHG emissions to at least 55 % below 1990 levels necessitates addressing carbon inequality within the EU [14]. According to the report on Carbon Inequality in 2030 by Oxfam, the consumption emissions of the poorest 50 % of the population in the EU are estimated to fall to the per capita level needed to limit global warming to 1.5 ⁰C by 2030, while the richest 10 % stand to be five to six times above this level. Data from the World Inequality Database show that in the EU, the carbon footprint — referring to per capita CO2 emissions from consumption — of the richest 10 % of the population was 5.0 times higher than that of the poorest 50 % in 2020. The ratio has stagnated at this level since 2015. The Member States with the widest carbon footprint gap between the top 10 % and the bottom 50 % were Luxembourg, Romania and Austria, with ratios of 7.1, 6.5 and 6.3, respectively, in 2020. In comparison, the gap was the narrowest in Malta and the Netherlands, at 3.9 and 4.0, respectively. Overall, carbon footprint inequality in the EU is somewhat smaller than in other parts of the world. For example, the ratio amounted to 5.8 in Japan and 6.5 in the United States. A much higher carbon inequality was measured in India and China, with ratios of 10.2 and 12.6, respectively.

Inequalities between countries

We live in an interconnected world, where problems and challenges — such as poverty, climate change or migration — are rarely confined to one country or region. Therefore, reducing inequalities between countries is important, not only from a social cohesion perspective, but also as a prerequisite for solving many interdependent problems. Cohesion between Member States is one of the EU’s objectives, as mentioned in the Treaty on European Union (article 3.3).

Economic disparities between EU countries in terms of GDP and household income have fallen strongly in recent years

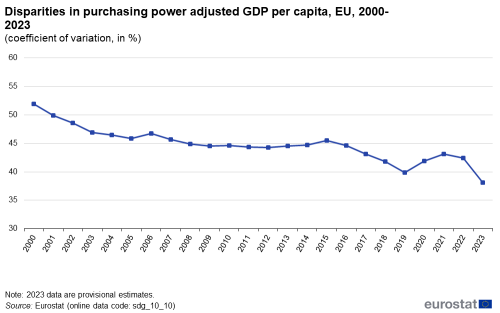

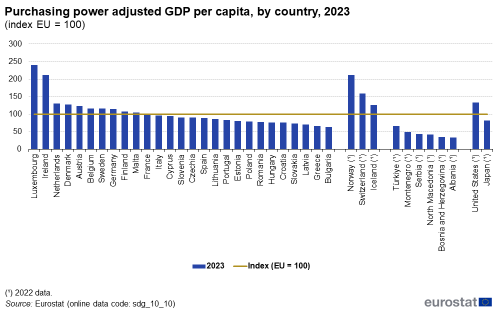

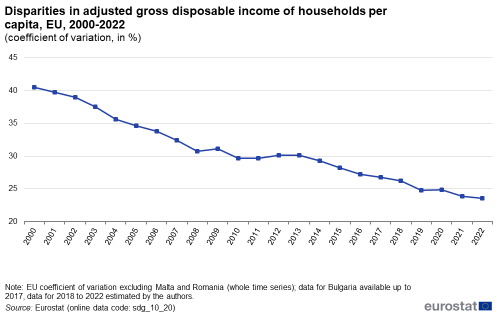

Not only have economic performance, incomes and living standards improved across the EU as a whole over time, they have also converged between countries. A way to measure such conversion is by looking at the coefficient of variation, expressed as the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean (in %). A lower coefficient of variation indicates less disparities between Member States. The two indicators used to measure this convergence show that inequalities between EU countries have decreased over the 15-year period assessed, even though the short-term trends are mixed.

The coefficient of variation in gross domestic product (GDP) per capita — expressed in purchasing power standards (PPS) — shows that economic disparities between Member States have narrowed since 2000, reaching 38.1 % in 2023. Most of this convergence took place in the period leading up to the 2008 economic crisis and between 2015 and 2019. After a temporary turnaround of the trend during the COVID-19 crisis in 2020 and 2021, when economic disparities between countries increased, the coefficient of variation resumed its decreasing trend in 2022 and 2023. The progress in economic convergence was particularly strong in 2023, when the coefficient of variation fell by 4.3 percentage points compared with 2022. At Member State level, purchasing power adjusted GDP per capita ranged from 64 % of the EU average in Bulgaria to 240 % in Luxembourg in 2023.

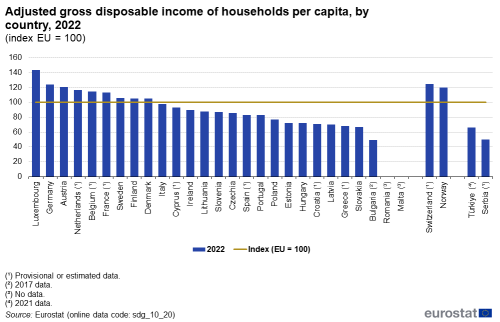

While GDP per capita is used to measure a country’s economic performance, adjusted gross household disposable income provides an indication of the average material well-being of people. Gross household disposable income reflects households’ purchasing power and ability to invest in goods and services or save for the future, by taking into account taxes, social contributions and in-kind social benefits. The coefficient of variation in gross household disposable income between Member States has significantly decreased over time, reaching 23.6 % in 2022. This figure is 3.2 percentage points less than in 2017 and an 8.8 percentage point improvement since 2007.

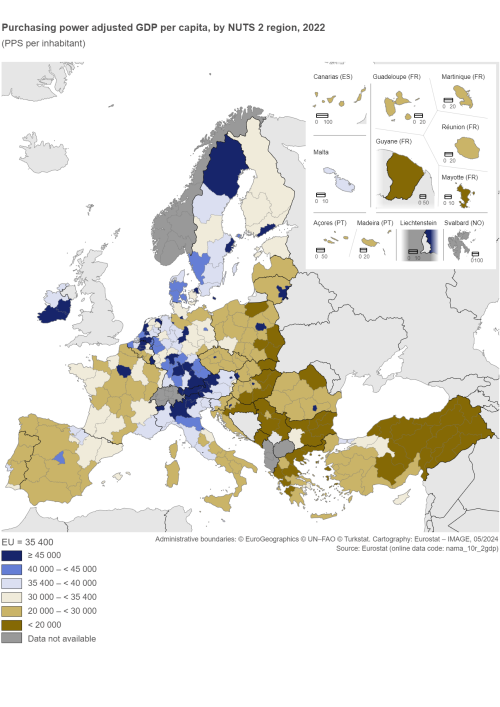

However, a clear north–south and west–east divide is evident when looking at the geographical distribution of GDP per capita and household income (from national accounts) in the EU. EU citizens living in northern and western European countries with above average GDP per capita levels had the highest gross disposable income per capita. At the other end of the scale were eastern and southern EU countries, which displayed gross household disposable incomes and GDP per capita levels below the EU average.

Migration and social inclusion

The Syrian conflict, unstable situations in Afghanistan and some African countries, crises in several Latin American countries such as Venezuela, Colombia, Honduras and Nicaragua, and the war in Iraq have contributed to an unprecedented surge of migration into the EU over the past few years. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has led to a mass movement of people fleeing the war to seek temporary protection in the EU. The successful integration of migrants is decisive for the future well-being, prosperity and cohesion of European societies. To ensure the social inclusion of immigrants and their children, it is essential to strengthen the conditions that will enable their participation in society, including their active participation in education and training and their integration into the labour market. Successful integration of migrants into the EU labour force has the potential to slow down the ongoing trend of population ageing and to address skills shortages.

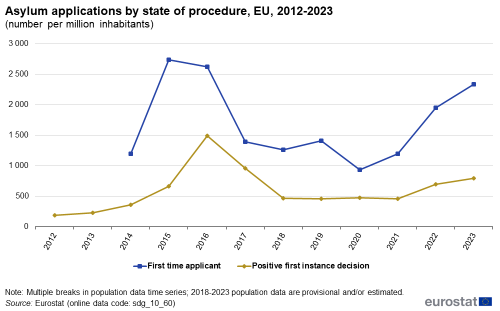

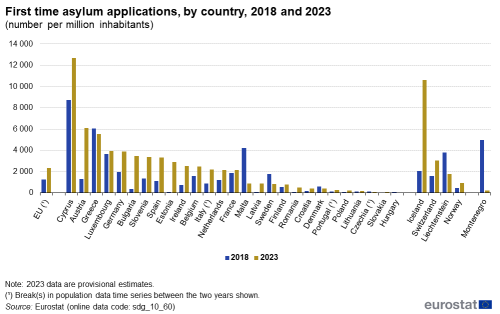

The number of asylum applications in the EU has risen strongly since 2020

The urge to seek international protection is one of the main reasons why people cross borders. In 2023, the EU received 1 049 020 first-time asylum applications [15], which is an almost 20 % increase since 2022. During 2023, around 358 000 people were granted protection status at the first instance in the EU [16]. In relation to the EU population, these numbers equal 2 338 first-time asylum applications and 798 positive first-instance decisions per million EU inhabitants in 2023.

Following a considerable fall (by one-third) in the number of first-time asylum seekers applying for international protection between 2019 and 2020, owing to the COVID-19 pandemic and related emergency measures such as movement restrictions [17], the EU has since seen a consistent rise in asylum applications. Moreover, following the displacement caused, the Council Decision of March 2022 enabled non-EU citizens fleeing Ukraine as a consequence of the Russian invasion on 24 February 2022 to receive immediate and temporary protection. At the end of February 2024, about 4.2 million displaced people were beneficiaries of this temporary protection in the EU. Germany and Poland hosted the highest absolute number of beneficiaries, providing temporary protection to more than half of all beneficiaries in the EU [18]. The asylum applications received by Member States were the highest in October 2023 for the second month in a row since the refugee crisis of 2015 and 2016. More than a quarter of these applications were made to Germany, and most of the applications were lodged by Syrians [19].

Despite some improvements in recent years, the social inclusion of non-EU citizens remains a challenge

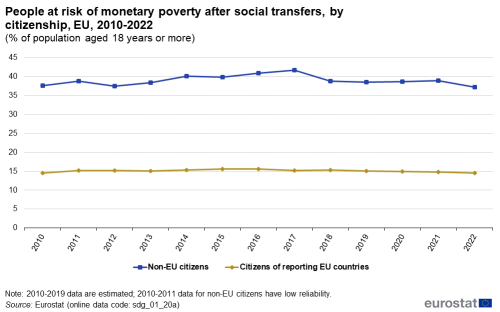

The social integration of migrants is monitored here by comparing the situation of non-EU citizens with citizens of EU Member States that reside in their home country —referred to as ‘home-country nationals’ in this publication — in the areas of poverty, education and the labour market. In all these areas, people from outside the EU fare less well than EU nationals. However, short-term trends have been mostly favourable, with the gap between home-country nationals and non-EU citizens closing or at least stagnating in almost all areas monitored here.

Trends in the citizenship gap for people at risk of monetary poverty after social transfers show that between 2017 and 2022, poverty rates remained quite stable for EU home-country nationals with a 0.7 percentage point improvement compared with 2017, while those for non-EU citizens fell by 4.6 percentage points over this period. This has contributed to the narrowing of the gap between the two groups by 3.9 percentage points since 2017 showing significant progress. Still, this gap remains large, with 37.2 % of non-EU citizens being at risk of monetary poverty (after social transfers) in 2022, compared with only 14.5 % of home-country nationals.

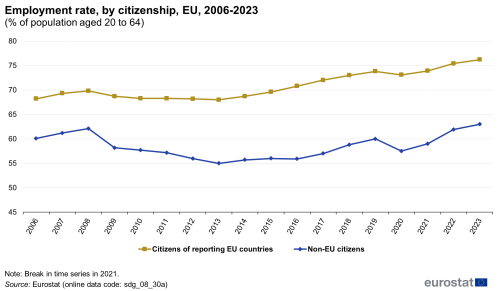

Between 2018 and 2023, the employment rate for EU home-country nationals aged 20 to 64 increased by 3.2 percentage points, while the rate for non-EU citizens grew by 4.2 percentage points. As a result, the gap between the two groups has narrowed by 1.0 percentage points since 2018. While 76.2 % of EU home-country nationals were employed in 2023, the rate for non-EU citizens stood at 63 %. Thus, despite the stronger improvement for non-EU citizens since 2018, the gap remains considerable, at 13.2 percentage points in 2023.

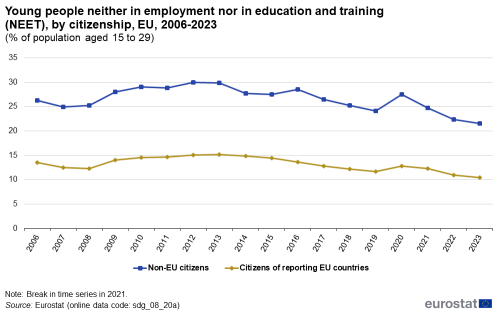

The gaps between home-country nationals and non-EU citizens in the area of education and training have evolved differently in recent years. The shares of young people not in employment nor in education and training (NEET) decreased for both groups between 2018 and 2023. The NEET rate for 15- to 29-year old non-EU citizens fell by 3.7 percentage points, reaching 21.5 % in 2023. For home-country nationals of the same age, the NEET rate decreased by 1.8 percentage points in the same period, amounting to 10.4 % in 2023. Thus, a narrowing of the gap by 1.9 percentage points has been visible since 2018. Despite these improvements, the citizenship gap between the two groups still amounted to 11.1 percentage points in 2023.

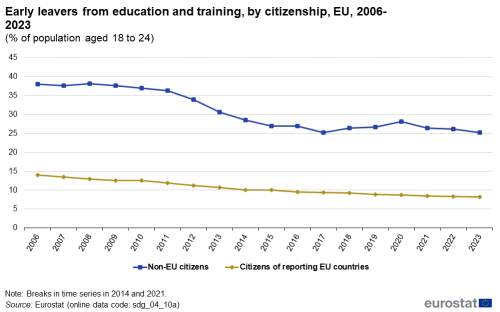

The most striking difference between non-EU citizens and EU home-country nationals is visible for 18- to 24-year-old early leavers from education and training. The early leaving rate of home-country nationals has fallen continuously since 2018, reaching 8.2 % in 2023. Over the same period, the early leaving rate for non-EU citizens experienced ups and downs and overall fell by 1.1 percentage points compared with 2018, reaching 25.3 % in 2023. As a result, the citizenship gap has narrowed slightly by 0.1 percentage points since 2018, reaching 17.1 percentage points in 2023. Because early school leaving and unemployment both have an impact on people’s future job opportunities and their lives in general, further efforts are needed to fully integrate young migrants into European societies.

Main indicators

The distribution of income can be measured by using, among others [20] the ratio of total equivalised disposable income received by the 20 % of the population with the highest income (top quintile) to that received by the 20 % of the population with the lowest income (lowest quintile). Equivalised disposable income is the total income of a household (after taxes and other deductions) that is available for spending or saving, divided by the number of household members converted into equivalised adults. Data presented in this section stem from the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC).

Note: y-axis does not start at 0.

Source: Eurostat (sdg_10_41)

Source: Eurostat (sdg_10_41)

This indicator measures the income share received by the bottom 40 % of the population (in terms of income). The income concept used is the total disposable household income, which is a households’ total income (after taxes and other deductions) that is available for spending or saving. Data presented in this section stem from the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC).

Note: y-axis does not start at 0.

Source: Eurostat (sdg_10_50)

Source: Eurostat (sdg_10_50)

Relative median at-risk-of-poverty gap

The relative median at-risk-of-poverty gap helps to quantify how poor the poor are by showing the distance between the median income of people living below the poverty threshold and the threshold itself, expressed in relation to the poverty threshold. The poverty threshold is set at 60 % of the national median equivalised disposable income of all people in a country and not for the EU as a whole. Data presented in this section stem from the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC).

Note: y-axis does not start at 0.

Source: Eurostat (sdg_10_30)

Source: Eurostat (sdg_10_30)

Disparities in GDP per capita

GDP per capita is calculated as the ratio of GDP to the average population in a specific year. Basic figures are expressed in purchasing power standards (PPS) which represent a common currency that eliminates differences in price levels between countries to allow meaningful volume comparisons of GDP. The disparities indicator for the EU is calculated as the coefficient of variation of the national figures.

Note: y-axis does not start at 0.

Source: Eurostat (sdg_10_10)

Source: Eurostat (sdg_10_10)

Source: Eurostat (NAMA_10R_2GDP)

Disparities in household income per capita

The adjusted gross disposable income of households reflects the purchasing power of households and their ability to invest in goods and services or save for the future, by accounting for taxes and social contributions and monetary in-kind social benefits. The disparities indicator for the EU is calculated as the coefficient of variation of the national figures in PPS per capita.

Note: y-axis does not start at 0.

Source: Eurostat (sdg_10_20)

Source: Eurostat (sdg_10_20)

Asylum applications

This indicator shows the number of first-time asylum applicants per million inhabitants and the number of positive first instance decisions per million inhabitants. A first-time applicant for international protection is a person who lodged an application for asylum for the first time in a given Member State. First-instance decisions are decisions granted by the respective authority acting as a first instance of the administrative or judicial asylum procedure in the receiving country. The source data are supplied to Eurostat by the national ministries of interior and related official agencies.

Source: Eurostat (sdg_10_60)

Source: Eurostat (sdg_10_60)

Presentation of additional multi-purpose indicators

Urban–rural gap for risk of poverty or social exclusion

Statistics on the degree of urbanisation classify local administrative units as ‘cities’, ‘towns and suburbs’ or ‘rural areas’ depending on population density and the total number of inhabitants. This classification is used to determine the difference in the shares of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion between cities and rural areas. Data presented in this section stem from the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC).

Note: y-axis does not start at 0.

Source: Eurostat (sdg_01_10a)

Source: Eurostat (sdg_01_10a)

Citizenship gaps between non-EU citizens and citizens of reporting EU countries

This section provides data for different indicators by citizenship. Data are shown for non-EU citizens, referring to citizens of non-EU Member States, and for citizens of the reporting countries, referring to citizens of EU Member States that reside in their home country. Data presented in this section stem from the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) and from the EU Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS).

Source: Eurostat (sdg_01_20a)

Source: Eurostat (sdg_04_10a)

Source: Eurostat (sdg_08_20a)

Source: Eurostat (sdg_08_30a)

Direct access to

More detailed information on EU SDG indicators for monitoring of progress towards the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), such as indicator relevance, definitions, methodological notes, background and potential linkages can be found in the introduction as well as in Annex II of the publication ’Sustainable development in the European Union — Monitoring report on progress towards the SDGs in an EU context — 2024 edition’.

Further reading on inequalities

- Eurofound (2021), Monitoring convergence in the European Union: Looking backwards to move forward – Upward convergence through crises, Challenges and prospects in the EU series, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

- Eurofound (2019), A more equal Europe? Convergence and the European Pillar of Social Rights, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

- European Migration Network (2023), Annual report on Migration and Asylum 2022, European Commission.

- European Commission (2023), Atlas of Migration 2023, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

- European Commission (2023), Employment and Social Developments in Europe, Annual Review 2023.

- European Commission, Common European Asylum System.

- OECD (2023), International Migration Outlook 2023.

- [OECD (2021), Does Inequality Matter? How People Perceive Economic Disparities and Social Mobility, OECD Publishing, Paris.

- OECD (2019), Under Pressure: The Squeezed Middle Class.

- OECD (2018), A Broken Social Elevator? How to Promote Social Mobility.

- World Inequality Lab (2022), World Inequality Report 2022.

Further data sources on inequalities

- Eurostat, Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income (online data code: ilc_di12).

- How's Life? Well-Being - OECD Statistics database.

- OECD Income (IDD) and Wealth (WDD) Distribution Databases.

- European Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex) (2020), Risk analysis for 2020.

- OECD (2023), Settling in — Indicators of Immigrant Integration 2023.

- World Inequality Database.

Notes

- ↑ OECD (2017), Understanding the socio-economic divide in Europe. Background report.

- ↑ Darvas, Z. and Wolff, B. (2016), An Anatomy of Inclusive Growth in Europe, pp.14–15.

- ↑ The term ‘income year’ is used here to emphasize that the income data collected for EU-SILC in a given year refer to the income situation of the previous year. The EU-SILC indicators provide insights on the economic well-being and other living conditions on EU residents based on data collected during a specific year, denoted as N. This data encompasses both the characteristics of households for that year (N) and the income from the preceding year, N-1. The income for year N-1 is an estimate for income of year N within EU-SILC. Income data collected for SILC refer to the situation in the previous year, meaning that data labelled as 2022 refer to people’s incomes in 2021. To emphasize this aspect, the analysis of SILC income data in this chapter uses the term ‘income year’, thereby highlighting that the data describe the situation in the year N-1 rather than in the year N when they were collected.

- ↑ In 2020, the German EU-SILC survey was integrated into the newly designed German microcensus, leading to a substantial break in the time series between 2019 and 2020, with income variables being the most affected by the break. For more information see the related information note. Additionally, further countries such as France also reported methodological changes in 2020, which also affected the EU total.

- ↑ European Commission, EU social indicators dataset: Inequality of opportunity — income dimension.

- ↑ European Commission, EU social indicators dataset: Inequality of opportunity — education dimension.

- ↑ European Commission (2022), Employment and social developments in Europe 2022, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

- ↑ European Platform for Investing in Children (EPIC) (2020), The Childcare Gap in EU Member States, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

- ↑ European Commission (2022), Employment and social developments in Europe 2022, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (sdg_01_10)).

- ↑ Volonteurope (2016), Rural isolation of citizens in Europe.

- ↑ European Commission (2022), Cohesion in Europe towards 2050 – Eighth report on economic, social and territorial cohesion, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

- ↑ European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2022), Roma in 10 European Countries. Main results, Vienna.

- ↑ Oxfam (2020), Confronting Carbon Inequality in the European Union.

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (migr_asyappctza)).

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (migr_asydcfsta)).

- ↑ European Asylum Support Office (2021), Asylum Trends 2020 preliminary overview.

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (migr_asytpsm)) and Eurostat (2023), Statistics Explained: Temporary protection for persons fleeing Ukraine — monthly statistics.

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (migr_asyappctzm))

- ↑ The income quintile share ratio looks at the two ends of the income distribution. Other indicators, such as the Gini index, measures total inequality along the whole income distribution.