Archive:Employment content in EU exports - an analysis with FIGARO data

Data extracted in July 2022.

Planned article update: July 2023.

Highlights

In 2020, the employment of 30 million persons in the EU was supported by exports to non-member countries, equivalent to just over one in seven of the 206 million persons employed in the EU.

As a share of total employment, the employment in each of the EU Member States that was supported by exports from any of the EU Member States peaked at nearly one quarter in Luxembourg (24 %) and Ireland (23 %).

Germany is by far the largest contributor to export-supported employment spillover in the EU: in 2020, 1.2 million persons employed in EU Member States other than Germany were supported by German exports.

Manufacturing exports supported 18 million persons employed in the EU in 2020, 59 % of all export-supported employment.

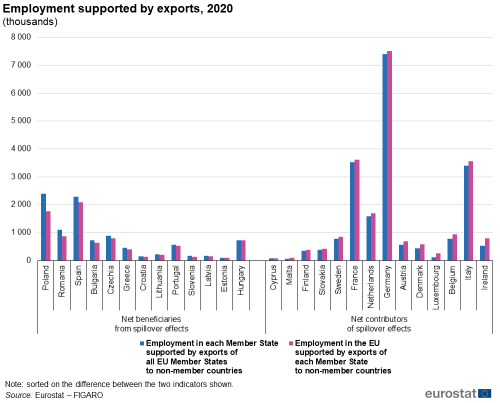

Share of employment in each Member State supported by EU exports, 2020

The production of goods and services requires inputs which may have been sourced domestically or globally. The final value of a product may well reflect value that has been added in many different stages through the combination of factors of production, including employment. The employment input may have been located in many different countries.

An analysis of the employment content of exports of goods and services can provide insight into international trade relations. This article aims to provide an indication of the relationship between employment in the European Union (EU) and the EU’s exports. This is done by analysing the employment content of EU exports at a detailed industry [1] level.

The article provides an overview of the data compiled using the FIGARO tables – Full International and Global Accounts for Research in input-Output analysis – and the Leontief input-output model (Miller and Blair, 2009). For more information, see the Data Sources and Context sections below.

Full article

Whole economy – all industries combined

Number and share of persons employed

The number of persons employed in the EU or in individual EU Member States that is supported by exports includes not only employment in enterprises that are directly exporting, but also in other enterprises which provide goods or services to support the production of exported goods and services; in other words, it includes employment in upstream enterprises. This may concern employment in enterprises in the same industry as the exporter or in a different one (depending, in part, how detailed an activity classification is used). Equally, exports by enterprises in one Member State may support employment in the same Member State or in a different one.

Regardless of whether presenting data for the EU as a whole or for individual EU Member States, all references to exports in this article concern exports to non-member countries, in other words extra-EU exports; trade between Member States is not considered.

In 2020, the employment of 29.9 million persons in the EU was supported by exports to non-member countries (Table 1). This export-supported employment accounted for 14.5 % of total employment (206.4 million), equivalent to just over one in seven persons employed within the EU.

In absolute terms, Germany was the EU Member State with the highest employment supported by EU exports (Figure 1): in 2020, the employment of 7.4 million persons in Germany was supported by exports from the EU, including exports from Germany itself. The level of export-supported employment in Germany was more than the combined level of export-supported employment in France (3.5 million) and Italy (3.4 million), which had the second and third highest levels (see Table 1). As a share of total employment, the employment in each of the EU Member States that was supported by exports to non-member countries ranged from just under 1 in 10 in Croatia (9.2 %) and Greece (9.8 %) to nearly one in four in Ireland (23.3 %) and Luxembourg (23.5 %).

Next to estimating export-supported employment in each Member State, FIGARO also provides insight into the employment anywhere in the EU that is supported by the exports from a particular EU Member State. Figure 1 compares these two indicators. The figure has been ranked on the difference between the two indicators.

The EU Member States on the left-hand side of Figure 1 are those that benefit more (in employment terms) from exports from other Member States than the employment they support in other Member States through their own exports: in other words, they are net beneficiaries from cross-border spillover effects (see Box 1). For example, employment of 2.4 million persons in Poland was supported by exports from any of the EU Member States (including from Poland), whereas employment of 1.8 million persons across the EU (some of which employed in Poland) was supported by exports from Poland; the difference – with Poland being a net beneficiary – was 636 000 persons employed. All three Baltic Member States were net beneficiaries from spillover effects, as were all of the eastern EU Member States except for Slovakia, as well as Spain, Greece and Portugal.

The EU Member States on the right-hand side of Figure 1 are those that benefit less in employment terms from exports of other Member States than the employment they support in other Member States through their own exports: these Member States are therefore net contributors of cross-border spillover effects. For example, employment of 3.4 million persons in Italy was supported by exports from any of the EU Member States (including from Italy), whereas employment of 3.6 million persons across the EU (some of which were in Italy) was supported by exports from Italy; the difference was 174 000 persons employed. All three Nordic Member States and most western Member States were net contributors of spillover effects, as were Italy, Malta, Cyprus and Slovakia.

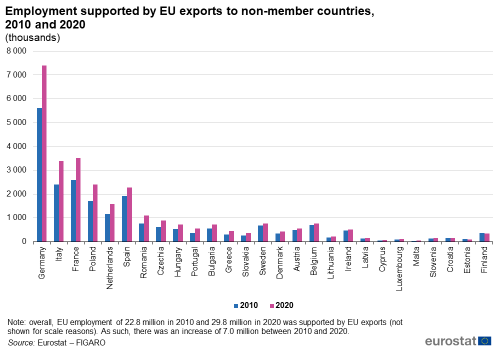

Figure 2 focuses on the trend in export-supported employment within each EU Member State (supported by exports from anywhere in the EU). Most EU Member States recorded an increase in export-supported employment between 2010 (during the recovery from the global financial and economic crisis) and 2020 (the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic). Small decreases in absolute and relative terms were observed in Bulgaria and Finland.

The share of export-supported employment in total employment in the EU increased from 11.7 % in 2010 to 14.5 % in 2020. Overall, export-supported employment in the EU increased by 6.8 million during this period. Just over one fifth of the increase (1.5 million more persons employed; 22.4 % of the EU increase) was located in Germany, with the next largest increases in France (691 000 more persons employed; 10.2 % of the EU increase), Croatia (538 000 more persons employed; 7.9 % of the EU increase), Austria (424 000 more persons employed; 6.2 % of the EU increase) and Italy (420 000 more persons employed; 6.2 % of the EU increase).

In relative terms, the largest increases in export-supported employment between 2010 and 2020 occurred in Malta (up 416 %) and Croatia (up 363 %), while export-supported employment also more than doubled in Cyprus, Luxembourg and Portugal.

Domestic and spillover effects

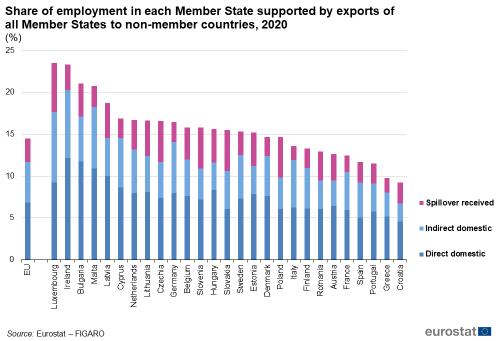

The share of export-supported employment within each EU Member State can be divided into two parts – the domestic effect and the spillover effect – with a further division of the domestic effect between direct and indirect effects: see Box 1 for more information. The share of total employment in each Member State related to these effects is presented in Figure 3.

Box 1: What are domestic and spillover effects?

The domestic effect is employment in a given EU Member State that is supported by its own exports. This employment may be in the same industry as the one that exports the goods or services (direct domestic effect) or in another industry (indirect domestic effect). As such, the indirect domestic effect is effectively an industrial spillover effect within a single EU Member State – it is employment in a particular industry that is supported by the exports of a different industry (within the same Member State).

The spillover effect reflects the employment in a given EU Member State that is supported by the exports of other Member States. For example, it includes employment in a Member State engaged in the production of intermediate inputs to be used in other Member States’ exports to non-member countries.

In this article, the split of the domestic effect into a direct and indirect effect is based on an analysis of the economy dividing it into 64 different industries (according to EU’s activity classification called NACE). Examples of industries at this level of detail are manufacturing, distributive trades, or information and communication services. At a more detailed level of classification, the direct domestic effect would be smaller and the indirect domestic effect would be larger. For example, it is common for manufactured goods to pass through several stages of processing (each resulting in an intermediate good) before being finished (typically as a capital or consumer good). If the final good is exported by the manufacturing industry, export-supported employment in upstream manufacturing processes in the same Member State would be considered as a direct domestic effect because manufacturing is considered as being just one industrial activity. If the analysis is done at a more disaggregated level, with manufacturing divided up into several activities, some of the upstream employment may be in manufacturing industries that are different from the exporting manufacturing industry, and would therefore be considered as an indirect domestic effect.

The direct domestic effect accounted for 6.8 % of total employment in the EU in 2020, while the indirect domestic effect accounted for 4.8 % and the spillover effect for 2.8 % (see Figure 3).

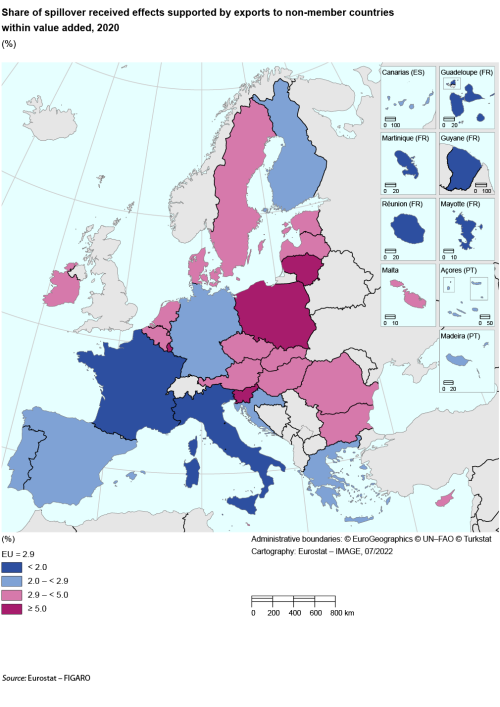

Among the EU Member States, the largest contributions to total employment of the direct domestic effect occurred in Ireland (12.2 %) and Bulgaria (11.7 %), while this effect also contributed 10.0 % or more of employment in Malta and Latvia. The lowest contribution of the direct domestic effect was observed in Croatia (4.6 %). The largest contribution to total employment of the indirect domestic effect was in Luxembourg (8.4 %), followed by Ireland (8.1 %) and Malta (7.4 %); the smallest contribution was again in Croatia (2.2 %). The largest contribution to total employment of the spillover effect was in Luxembourg (5.9 %), followed by Slovakia, Czechia, Slovenia (all 4.9 %) and Poland (4.8 %), while the smallest contributions occurred in Greece and Italy (both 1.7 %) – see Map 1.

The direct domestic effect – that is, employment in an industry in a specific EU Member State that is supported by exports from that same industry in that same Member State – accounted for 47.3 % of all export-supported employment across the EU Member States in 2020. The direct domestic effect was the dominant effect in all Member States (see Figure 3), accounting for more than half of export-supported employment in 11 of them. In relative terms, the largest impact of the direct domestic effect within all export-supported employment was 55.7 %, recorded for Bulgaria; the smallest impact was 39.0 %, recorded for Slovakia.

The indirect domestic effect accounted for 33.4 % of all export-supported employment in the EU Member States in 2020. This was the second largest effect (among the three shown in Figure 3) in two thirds of the EU Member States: in Poland, Slovenia, Hungary, Estonia, Czechia, Croatia, Slovakia, Austria and Romania, the spillover effect was larger. The indirect domestic effect accounted for one fifth to two fifths of export-supported employment in all but one of the Member States: the lowest share was 21.0 % in Hungary while the highest share – over two fifths – was 41.8 % in Italy.

The spillover effect accounted for 19.3 % of all export-supported employment in the EU Member States in 2020. The spillover effect accounted for 12.1 % of export-supported employment in Malta, while there were also relatively low shares in the three largest EU Member States: 12.3 % in Italy, 14.7 % in Germany and 15.7 % in France. The spillover effect accounted for one quarter or more of export-supported employment in 11 Member States, peaking at 32.9 % in Poland.

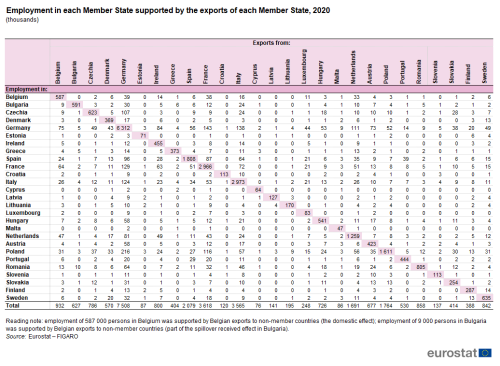

Export-supported employment from the domestic and spillover effects are shown in absolute values in Table 2. Employment from the domestic effect is shown in the shaded cells running in a diagonal line from the top left to the bottom right of the table.

The largest level of export-supported employment resulting from the domestic effect was clearly in Germany, where 6.3 million persons employed were supported by Germany’s own exports, with the next largest domestic effects observed in Italy and France (both 3.0 million).

The single largest spillover effect between any pair of countries was the 216 000 persons employed in Poland in 2020 who were supported by German exports. Four other country pairings had spillover effects of more than 120 000 persons employed:

- 143 000 and 138 000 persons employed in Germany who were supported by French and Italian exports respectively;

- 129 000 persons employed in France who were supported by German exports;

- 124 000 persons employed in Italy who were supported by German exports.

Germany was by far the largest contributor of export-supported employment resulting from spillover effects: 1.2 million persons employed in 2020 in EU Member States other than Germany were supported by German exports. As noted above, 216 000 of these were in Poland, 129 000 in France and 124 000 in Italy, while Czechia (107 000), Spain (96 000), the Netherlands (81 000), Romania (64 000), Austria (58 000) and Hungary (also 58 000) all had more than 50 000 persons employed who were supported by German exports. For comparison, the next highest contributors to employment spillover were France (652 000 persons employed in other Member States), Italy (592 000) and the Netherlands (432 000). The high figure for the Netherlands may reflect, among other factors, the large distributive trades industry in the Netherlands, specifically trade through the port of Rotterdam – the largest maritime port within the EU in terms of the quantity of freight handled.

Industries

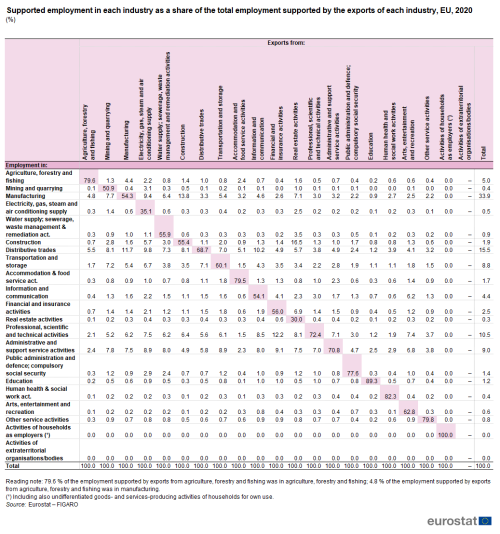

Whereas Table 2 focused on employment in EU Member States that was supported by exports, Table 3 provides a similar analysis for industries. This presentation reveals the extent to which employment in specific industries is dependent on exports from the same industry or from other (downstream) industries. Unlike Table 2, Table 3 does not show absolute values of the number of persons employed but instead presents employment shares. The totals in each column sum to 100 %: each column shows the distribution (among employing industries) of employment that is supported by exports from a specific industry.

The share of export-supported employment within the same industry as the exporting industry is shown in the shaded cells running in a diagonal line from the top left to the bottom right of the table. The highest share [2] was observed for education: in 2020, 89.3 % of all employment in the EU that was supported by exports from the education industry was in the education industry itself. Twenty other industries received the remaining 10.7 % of employment supported by exports from the education industry, with the administrative and support service activities industry as the largest beneficiary (2.5 %) of export-supported employment from industrial spillover effects.

By contrast, two industries had shares along this diagonal that were below 50 %.

- For employment supported by exports from the electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply industry, 35.1 % was in the same industry, 9.8 % was in distributive trades, 9.4 % in manufacturing and 8.9 % in administrative and support service activities.

- For employment supported by exports from the real estate activities industry, 30.0 % was in the same industry, 16.5 % was in construction, 8.1 % in professional, scientific and technical activities (which includes, among others, the activities of notaries, architectural and engineering services), 7.5 % in administrative and support service activities, 7.1 % in manufacturing, and 6.9 % in financial and insurance activities.

The single largest industrial spillover effect between any pair of industries was the 16.5 % noted above for employment in construction supported by exports from the real estate industry. Four other industry pairings had industrial spillover effects exceeding 10% of the employment supported by exports from a particular industry:

- 13.8 % of the employment supported by construction exports was in manufacturing;

- 12.2 % of the employment supported by exports of the financial and insurance activities industry was in the professional, scientific and technical activities industry;

- 11.7 % of the employment supported by manufacturing exports was in distributive trades;

- 10.2 % of the employment supported by information and communication services was in distributive trades.

In absolute terms, the picture is somewhat different, as manufacturing exports alone supported 17.8 million persons employed in the EU in 2020, equivalent to around three fifths (59.4 %) of all export-supported employment in the EU. Some 9.6 million of this total were employed within manufacturing itself, with the remaining 8.1 million persons representing the industrial spillover effect within the other 20 industries. The eight largest industry pairings for export-supported employment resulting from industrial spillover effects all concerned employment in industries outside the manufacturing industry itself that were supported by manufacturing exports. For example, 2.1 million persons employed in distributive trades were supported by manufacturing exports, as were 1.3 million persons in administrative and support service activities, 1.1 million persons in professional, scientific and technical activities, and 964 000 persons in transportation and storage (see Figure 4).

The largest pairing of industrial spillover effects that did not involve manufacturing was the 208 000 persons employed in transportation and storage activities who were supported by exports from distributive trades.

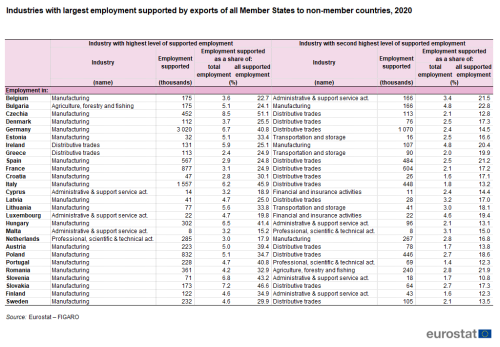

Table 4 identifies for each of the EU Member States which two industries had the highest level of export-supported employment. In 20 Member States, manufacturing had the highest level of export-supported employment in 2020, while there were three more Member States where manufacturing had the second highest level.

Greece, Cyprus, Luxembourg and Malta were exceptions because manufacturing was not one of the two industries with the highest level of export-supported employment. The next most common industry in Table 4 was distributive trades, which had the highest level of export-supported employment in two Member States and the second highest in 12 more.

Five other industries appear in Table 4:

- administrative and support service activities – seven times (Belgium, Cyprus, Luxembourg, Hungary, Malta, Slovenia and Finland);

- professional, scientific and technical activities – three times (Malta, the Netherlands and Portugal);

- transportation and storage – three times (Estonia, Greece and Lithuania);

- agriculture, forestry and fishing – twice (Bulgaria and Romania);

- financial and insurance activities – twice (Cyprus and Luxembourg).

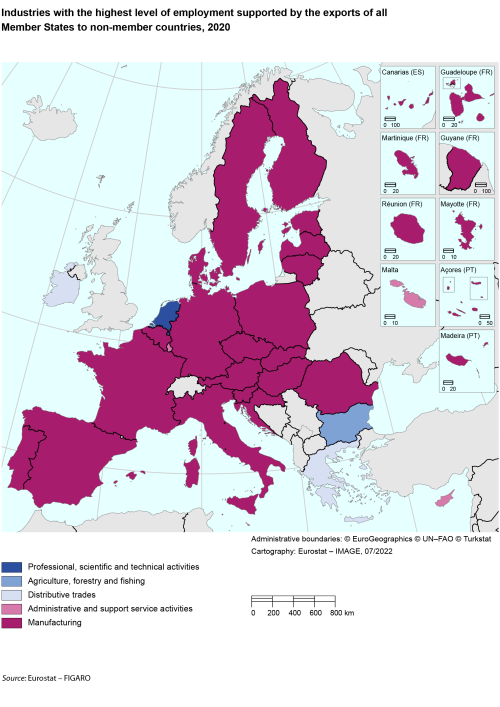

Earlier we noted that a considerable number of persons employed in other industries are supported by exports from the manufacturing industry. Still, in most EU Member States – including the five largest ones – manufacturing had the highest absolute level of employment supported by exports (from any industry), as can be seen from Map 2.

Source data for tables and graphs

![]() Employment content in EU exports: tables and figures

Employment content in EU exports: tables and figures

All FIGARO data for employment are available from the following files:

Data sources

FIGARO tables are a statistical product of the integrated global accounts for economic modelling. They link national accounts and data on business, trade and jobs for the EU Member States, the United States and 17 main EU trading partners (Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, India, Indonesia, Japan, Mexico, Norway, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, South Korea, Switzerland, Turkey and the United Kingdom) represented in the OECD ICIO (inter-country input-output tables); a ‘rest of the world’ region completes the FIGARO tables.

Internationally, the FIGARO tables contribute as much as possible to the OECD ‘Global regional TiVA initiative’ and to the compilation of the OECD global inter-country input-output tables by providing data for the EU and its Member States.

The FIGARO tables present the relationship between the EU economies and their trading partners at a detailed level of 64 industries and 64 products, as defined in the ‘ESA 2010 National accounts transmission program’.

Frequency and availability

FIGARO tables are available from 2010 to 2020 (period T–24 months, T being the year of release). As of 2021, they are produced annually by Eurostat.

The FIGARO tables will be updated on an annual basis with the latest available reference year (for example data for 2021 in 2023). The time series is in line with the latest macroeconomic aggregates.

More information

For more information, please refer to the FIGARO dedicated section.

Context

Partners

The FIGARO tables result from a collaborative project between Eurostat and the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre.

The FIGARO tables contribute to the OECD’s global inter-country input-output tables published under the TiVA initiative, which considers the value added by each country in the production of goods and services that are consumed worldwide.

Purpose

The FIGARO tables provide the first official inter-country supply, use and input-output data for the EU. They are a tool for analysing the social, economic and environmental effects of globalisation in the EU. These may be analysed through studies on competitiveness, growth, productivity, employment, environmental footprint and international trade (for example, analyses of global value chains).

The tables are used to evaluate EU policies and assess the economic performance of the EU (or the euro area or individual EU Member States) in the world.

Notes

- ↑ The terms industry/industries are used in this article as synonyms for activity/activities, in the sense of the activities listed in the NACE classification.

- ↑ Leaving aside the small and somewhat atypical activities of households as employers and the undifferentiated goods- and services-producing activities of households for own use.

Direct access to

- Data can be accessed through the dedicated section as csv files and Rdata files.