Archive:European Neighbourhood Policy - South - international trade in goods statistics

Data extracted in June 2021.

Planned article update: March 2022.

Highlights

All of the European Neighbourhood Policy-South countries that reported data recorded deficits for trade in goods in 2019.

In 2019, the EU was a key partner for trade in goods for most European Neighbourhood Policy-South countries, particularly Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria.

Israel increased its total exports by 18.1 percentage points of GDP and Morocco by 16.7 percentage points during the period 2009 – 2019, the most among the European Neighbourhood Policy-South countries.

(% share of total exports / imports)

Source: Eurostat (enps_ext_sitc)

This article is part of an online publication and provides data on international trade in goods for 9 of the 10 countries that form the European Neighbourhood Policy-South (ENP-South) region — Algeria, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Palestine [1] and Tunisia; no recent data available for Syria or, for international trade, for Lebanon.

The article highlights some of the key indicators for tracing developments in the international trade of the ENP-South region over the period 2009-2019, with information on exports, imports and the trade balance. It is followed by an examination of trade between ENP-South countries and the EU from the perspective of the ENP-South countries, using data reported by the ENP-South countries themselves. It also presents an analysis of international trade between the regions by broad product groups (based on the standard international trade classification (SITC)).

Full article

Exports, imports and the trade balance

International trade statistics track the value and quantity of goods traded between countries. They are the official source of information on exports, imports and the trade balance, the difference between them.

Long term global trends have seen trade increasing as a proportion of gross domestic product (GDP in most countries. This has been an important element of globalisation, although far from the only one. Countries that are growing fast or are undergoing or recovering from economic difficulties may wish to run trade deficits, in which the value of imports is greater than that of exports. Countries that specialise in providing services to the rest of the world, such as tourism or business services, may also run consistent trade deficits, since services are not included in the statistics of exports and imports of goods. The balance of payments includes data on both trade in goods and in services.

Exports and imports as a percentage of GDP are often used as a measure of a country’s openness to world trade. Smaller countries tend to have higher levels of trade openness than larger ones, since there are fewer opportunities for buying and selling domestically produced goods. The relationship between trade openness and income (measured as GDP per capita) is more complicated, although low income countries generally have low trade openness.

Table 1 shows the basic data on exports, imports and the balance of payments in million euro. The data in Figures 1, 2 and 3 respectively show the exports, imports and trade balance of the European Neighbourhood South countries and the EU as a percentage of GDP. These allow a focus on the relative importance of trade flows and balance to the size of the economies concerned.

The main interest of Table 1 is to show the absolute sizes of the trade flows. Looking at 2019 data, the largest exporter of goods among the ENP-South countries was Israel, followed by Algeria, Egypt and Morocco, which had exports of similar magnitudes. Tunisia had about half the export values of these three countries. Libya (2016 data), Jordan (2018 data) and Palestine had considerably smaller exports.

Over the period 2009-2019, Palestine had the largest annual average export growth rate at 10.6 % per year, although from a very low base. Morocco had a very similar growth rate, at 10.2 %, although this figure may have been affected by a break in the series in 2013, due to the adoption of the general system of trade. Egypt’s annual average growth in exports 2009-2019 was 4.7 %; Israel’s 4.2 %; Tunisia’s 2.6 % and Jordan’s 2.0 % to 2018. Algeria’s exports shrank marginally by an annual average of -0.3 % and Libya’s diminished by an average -10.7 % over 2009-2016.

The largest importers in the ENP-South region in 2019 were Egypt and Israel, with virtually identical data. They were followed by Morocco, at around two-thirds their value, and by Algeria, at just over half Egypt’s imports. Smaller importers in descending order were Tunisia, Jordan (2018 data), Libya (2016 data) and Palestine.

The fastest growing importer over 2009-2019 was again Palestine, from a very low base, at an annual average increase of 8.9 %, followed by Egypt, at 7.9 %. Next was Israel at 7.2 %, and Morocco, at 6.9 %, although the break in the series in 2013 may have affected this result. Jordan’s imports increased by an annual average 3.9 % over 2009-2018; Tunisia’s by 3.5 % over 2009-2019. Libya reported imports at about the same level in 2016 as in 2009, following an initial strong increase in 2010, followed by falls in 2015 and 2016 (data for 2011-20103 not available); overall, the resulting average growth rate over 2009-2016 was a moderate 0.4 %.

The European Union’s exports of goods are around 14 times larger than the ENP-South as a whole and its imports almost eight times larger. Its exports have grown by an annual average of 6.1 % over 2009-2019 and its imports by 5.0 %.

(million EUR)

Source: Eurostat (ext_lt_intratrd) and (enps_ext_sitc)

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate, respectively, exports and imports of goods as percentages of gross domestic product (GDP). These are measures of the importance of international trade flows to each economy that are comparable both over time and between countries. Openness to trade is reported as either the sum or the average of these two ratios – the sum will be used in this analysis.

Israel had the highest ratio of exports to GDP in 2019, at 53.1 %; the second largest ratio of imports to GDP in 2019, at 69.6 %; the greatest openness to trade, at 122.8 % of GDP; and the greatest increase in trade openness from 2009 to 2019, at 53.1 percentage points.

Egypt had the largest ratio of imports to GDP in 2019, at 69.9 %; a ratio of exports to GDP of 27.9 %, just over half of Israel’s exports ratio; the second highest degree of openness to trade, at 97.9 %; and the second greatest increase in openness over 2009-2019, at 47.6 percentage points.

Morocco was the ENP-South country third most open to trade in 2019, at 73.2 % of GDP. Its exports accounted for 26.9 % of GDP and its imports, 46.4 % of GDP. Its degree of openness to trade increased by 39.2 percentage points from 2009 to 2019.

Algeria’s exports were equal to 32.5 % of GDP in 2019 and its imports, 38.1 %. Its degree of openness was therefore 70.6 %, an increase of 8.3 percentage points over 2009.

Tunisia’s exports were equivalent to 13.6 % of its GDP in 2019 and its imports, 19.7 %. Its openness to trade was 33.3 % of GDP in 2019 and the increase in this measure since 2009, 8.8 percentage points.

In 2018, Jordan’s exports were equal to 5.6 % of its GDP, its imports 14.7 % and thus its degree of openness, 20.3 %. Since 2009, its degree of openness had risen by 5.2 percentage points.

Libya’s exports in 2016 were 9.0 % of its GDP, whereas they had been as high as 28.0 % of GDP in 2010. Its 2016 imports, at 9.6 % of GDP, were also lower than the 2014 figure of 13.8 %. The 2016 degree of openness, the most recent year that this measure can be calculated, was 18.6 % of GDP, a decline of -10.6 percentage points from 2009.

Palestine’s exports of goods made up only 1.0 % of its GDP in 2019; and its imports, 6.0 %. Its degree of openness in 2019 was 7.1 %, indicating a closed economy. Nevertheless, this was a 4.1 percentage point increase over 2009.

The EU’s exports of goods to the rest of the world were in 2019 equivalent to 15.3 % of its GDP; and its imports, 13.9 %, yielding a degree of openness to trade of 29.2 %. This was an increase of 6.7 percentage points over 2009.

(as % of GDP)

Source: Eurostat (ext_lt_intratrd), (enps_ext_sitc) and (nama_10_gdp)

(as % of GDP)

Source: Eurostat (ext_lt_intratrd), (enps_ext_sitc) and (nama_10_gdp)

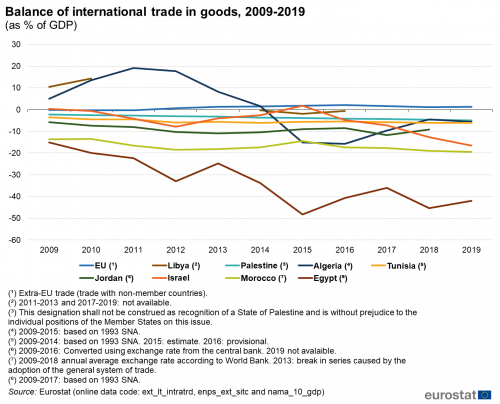

Figure 3 shows the balance of trade in goods for the ENP-South countries and the EU for the period 2009-2019 as a percentage of GDP. This provides a measure of the size of trade surpluses and deficits that is comparable over time and between countries. Countries’ ability to run trade deficits depends on many factors, including their non-goods international earnings from items such as provision of services, including tourism; factor earnings, including from labour; and remittances from abroad.

The trend over the 2009-2019 time period has been toward increasing deficits in all ENP-South countries, although at different levels. For every country in the region, the smallest deficits and largest surpluses occurred earlier in the period than the largest deficits. The only countries to run trade surpluses in some of the earlier years of the period were the hydrocarbon exporters Algeria and Libya, as well as, to a more modest extent, Israel in 2009 and 2015.

Some of the largest trade deficits in the ENP-East region were registered by Egypt, with its deficit at its greatest magnitude in 2015, at 48.2 % of GDP. Deficits early in the period were smaller, in particular in 2009 at 15.1 % of GDP. The 2019 value was 42.0 % of GDP. Morocco has also run consistent deficits, the smallest of which was 13.5 % of GDP in 2010. Its largest deficit occurred in 2019, at 19.5 % of GDP. Jordan’s smallest deficit occurred in 2009 at 5.8 % of GDP, and its largest in 2017, at 11.7 % of GDP. The most recent value, in 2018, was 9.1 % of GDP.

Tunisia has run a fairly consistent goods trade deficit, the smallest value of which was 3.5 % of GDP in 2009 and the largest 6.2 % in 2014. The 2019 deficit was 6.0 % of GDP. Israel’s trade balance started the period in 2009 with a 0.4 % surplus, which then deteriorated to a deficit of 7.9 % of GDP in 2012. The trade balance then improved again to a surplus of 1.8 % of GDP in 2015 before moving again into deficit, the largest value of which over the whole time period was in 2019 at 16.5 % of GDP.

Palestine has maintained a modest although somewhat deteriorating trade deficit over 2009-2019. The period started off with its smallest deficit, at 2.2 % of GDP and ended with its largest, at 5.0 % of GDP. Algeria started the period with a surplus of 4.9 % of GDP in 2009. The surplus then increased to 19.2 % of GDP in 2011. There was then a continual decline in the trade balance to a deficit of 15.8 % of GDP in 2016. The deficit has since moderated to 5.6 % in 2019.

The data is not continuous for Libya but in 2009, it ran a goods surplus of 10.5 % of GDP, increasing the next year to 14.4 %. The next data available is for 2014, when it ran a small deficit, with the observed minimum value over the period occurring in 2015, a deficit of 1.9 %. The most recent data is for 2016, a deficit of 0.6 % of GDP.

The EU’s trade balance as a percentage of GDP has ranged from a deficit of 0.4 % in 2011 to a surplus of 2.1 % in 2016. In 2019, the surplus was 1.4 % of GDP.

(as % of GDP)

Source: Eurostat (ext_lt_intratrd), (enps_ext_sitc) and (nama_10_gdp)

Trade between the EU and ENP-South countries

Figure 4 shows each country’s exports and imports with the EU for 2009 and 2019 as shares of their total exports and imports of goods.

In 2019, the EU accounted for a majority of the exports of Algeria, at 57.0 %, while EU imports into Algeria were 44.3 % of the total. Tunisia’s EU imports were 50.4 % of its total and its exports to the EU were 71.7 %. Morocco imported 51.4 % of its total from the EU and exported 64.4 % to the EU. In Egypt, the EU’s share of both exports and imports was around one quarter, at 25.3 % and 25.2 % respectively. The EU accounted for 21.1 % of Israel’s exports in 2019 and 32.1 % of its imports. The EU was the source of 11.7 % of Palestine’s imports and almost none of its direct exports (0.8 %).

(% share of total exports / imports)

Source: Eurostat (enps_ext_sitc)

Trade in goods by broad group of products

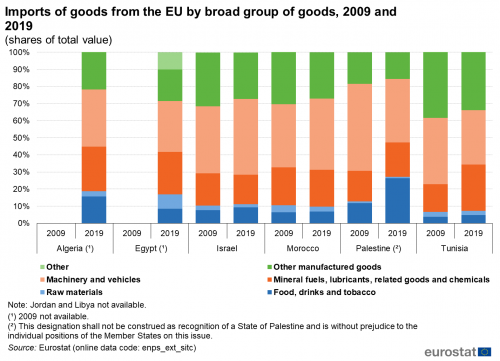

Figures 5 and 6 provide, for each of the European Neighbourhood Policy – South countries, a breakdown of their exports and imports to and from the EU in million Euro, analysed by broad group of goods and presented as shares of total trade flows. The ten main sections of the Standard international trade classification (SITC Rev.4) have been grouped into six product groups for the purpose of this analysis.

Looking at Figure 5, exports from Algeria to the EU in 2019 were almost exclusively (98.8 %) of Mineral fuels, lubricants, related goods and chemicals (SITC sections 3 and 5), unsurprisingly for a hydrocarbons producer. The majority of Egypt’s exports to the EU in 2019, 52.9 %, were also from this sector. Other manufactured goods (which cover SITC Sections 6 and 8) accounted for a further 23.5 % of exports. Mineral fuels, lubricants, related goods and chemicals provided 36.8 % of Israel’s exports of goods to the EU in 2019; Other manufactured goods 28.7 %; and Machinery and vehicles (SITC section 7), 25.9 %.

Machinery and vehicles made up 45.5 % of Morocco’s exports to the EU in 2019; Other manufactured goods 25.3 %; and Food, drinks and tobacco (SITC sections 0, 1 and 4) 20.4 %. Machinery and vehicles also accounted for 43.0 % of Tunisia’s exports to the EU in 2019; and Other manufactured goods 41.5 %. From Figure 4, we know that Palestine direct exports to the EU are minimal. Nevertheless, 73.5 % of them were made up of Food, drinks and tobacco.

(shares of total value)

Source: Eurostat (enps_ext_sitc)

From Figure 6, it can be seen that 33.3 % of Algeria’s imports of goods from the EU in 2019 consisted of Machinery and vehicles, together with a further 26.2 % of Mineral fuels, lubricants, related goods and chemicals; and 21.8 % of Other manufactured goods. Egypt’s imports from the EU included 29.6 % of Machinery and vehicles and 24.8 % of Mineral fuels, lubricants, related goods and chemicals.

Israel’s imports of goods from the EU in 2019 were made up of 44.3 % of Machinery and vehicles; 27.1 % of Other manufactured goods; and 17.3 % of Mineral fuels, lubricants, related goods and chemicals. Similarly, 41.6 % of Morocco’s imports from the EU consisted of Machinery and vehicles, 27.1 % of Other manufactured goods and 21.5 % of Mineral fuels, lubricants, related goods and chemicals. Palestine’s limited imports from the EU included 37.1 % of Machinery and vehicles; 26.3 % of Food, drinks and tobacco; and 20.2 % of Mineral fuels, lubricants, related goods and chemicals. Tunisia’s imports from the EU in 2019 comprised 33.8 % Other manufactured goods, 31.9 % Machinery and vehicles and 27.0 % Mineral fuels, lubricants, related goods and chemicals.

(shares of total value)

Source: Eurostat (enps_ext_sitc)

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

The data for ENP-South countries are supplied by and under the responsibility of the national statistical authorities of each country on a voluntary basis. The majority of the data presented in this article result from an annual data collection cycle that has been established by Eurostat. No recent data are available from Syria. These statistics are available free-of-charge on Eurostat’s website, together with a range of different indicators covering most socio-economic areas. More data are available from the United Nations’ Comtrade database.

Tables in this article use the following notation:

| Value in italics | data value is forecasted, provisional or estimated and is therefore likely to change; |

| : | not available, confidential or unreliable value; |

| – | not applicable. |

Context

The EU has a common international trade policy, often referred to as the common commercial policy. In other words, the EU acts as a single entity on trade issues, including issues related to the World Trade Organisation (WTO). In these cases, the European Commission negotiates trade agreements and represents Europe’s interests on behalf of the EU Member States.

The economic impact of globalisation has had a considerable effect on international trade, as well as financial flows. The EU seeks to promote the development of free-trade as an instrument for stimulating economic growth and enhancing competitiveness. International trade statistics are of prime importance for both public sector (decision makers nationally, within the EU and internationally) and private users (in particular, businesses who wish to analyse export market opportunities), as they provide valuable information on developments regarding the exchange of goods between specific geographical areas.

The European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP), launched in 2004, supports and fosters stability, security and prosperity in the EU’s neighbourhood. The ENP was revised in 2015. The main principles of the revised policy are a tailored approach to partner countries; flexibility; joint ownership; greater involvement of EU member states and shared responsibility. The ENP aims to deepen engagement with civil society and social partners. It offers partner countries greater access to the EU's market and regulatory framework, standards and internal agencies and programmes.

The Joint Communication by the European External Action Service and the European Commission on Renewed Partnership with the Southern Neighbourhood, accompanied by an EU Economic and Investment Plan for our Southern Neighbours, of 9 February 2021 further strengthens cooperation with the ENP-South countries.

The main objective of Euro-Mediterranean cooperation in statistics is to enable the production and dissemination of reliable and comparable data, in line with European and international norms and standards.

Reliable and comparable data are essential for evidence-based decision-making. They are needed to monitor the implementation of the agreements between the EU and the ENP-South countries, the impact of policy interventions and the reaching of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The EU has been supporting statistical capacity building in the region for a number of years through bilateral and regional capacity-building. This takes the form of technical assistance to partner countries’ national statistical authorities through targeted assistance programmes and activities such as training courses, working groups and workshops, exchange of best practice and the transfer of statistical know-how. Additional information on the policy context of the ENP is provided here.

Notes

- ↑ This designation shall not be construed as recognition of a State of Palestine and is without prejudice to the individual positions of the Member States on this issue.

Direct access to

Books

Leaflets

- Basic figures on the European Neighbourhood Policy — South countries — 2019 edition

- Basic figures on the European Neighbourhood Policy — South countries — 2018 edition

- Basic figures on the European Neighbourhood Policy — South countries — 2016 edition

- Basic figures on the European Neighbourhood Policy — South countries — 2015 edition

- International trade in goods for the European neighbourhood policy-South countries — 2018 edition

Factsheets

- International trade in goods (enps_ext)

- Trade value in goods by SITC product group (enps_ext_sitc)

- International trade in goods - aggregated data (ext_go_agg)

- International trade in goods - long-term indicators (ext_go_lti)

- Southern European Neighbourhood Policy countries (ENP-South) (enps) (ESMS metadata file — enps_esms)

- International trade in goods statistics — European Union (ESMS metadata file — ext_go_agg_esms)

- Quality report on European statistics on international trade in goods — 2016-2019 data — 2020 edition

- User guide on European statistics on international trade in goods — 2020 edition