Archive:The EU in the world - economy and finance

Data extracted in April 2018.

Planned article update: June 2019.

Highlights

G20 members accounted for 86.2 % of the world’s GDP in 2016.

China and India had the highest GDP growth between 2006 and 2016 among the G20 members.

Relative to GDP, Saudi Arabia moved from the largest government surplus in 2006 among the G20 members to the largest government deficit in 2016.

Among the G20 members Japan and the United States recorded the largest increases in government debt between 2006 and 2016 and had the largest levels of debt relative to GDP in 2016.

General government debt, 2016

This article is part of a set of statistical articles based on Eurostat’s publication The EU in the world 2018.

The article presents indicators from various areas, such as national accounts, government finance, exchange rates and interest rates, consumer prices, and the balance of payments in the European Union (EU) and the 15 non-EU members of the Group of Twenty (G20). It gives an insight into the EU’s economy in comparison with the major economies in the rest of the world, such as its counterparts in the so-called Triad — Japan and the United States — and the BRICS composed of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa.

Full article

National accounts

G20 members accounted for 86.2 % of the world’s GDP in 2016

In 2016, the total economic output of the world, as measured by gross domestic product (GDP), was valued at almost EUR 68.3 trillion, of which the G20 members accounted for 86.2 %, some 2.2 percentage points less than in 2006. The United States accounted for a 24.6 % share of the world’s GDP in 2016, moving ahead of the EU-28 whose share fell to 21.8 % (see Figure 1); note these relative shares are based on current price series in euro terms, reflecting market exchange rates. The Chinese share of world GDP rose from 5.4 % in 2006 to 14.8 % in 2016, moving ahead of Japan (6.5 % in 2016). To put the rapid pace of recent Chinese growth into context, in current price terms China’s GDP in 2016 was EUR 7 925 billion higher than it was in 2006, an increase equivalent to the combined GDP in 2016 of the nine smallest G20 economies (South Korea, Australia, Russia, Mexico, Indonesia, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Argentina and South Africa). The share of world GDP contributed by India also increased greatly, such that it moved from the 10th largest G20 economy in 2006 (leaving aside the four G20 EU Member States) to become the fifth largest by 2016.

(% of world total)

Source: Eurostat (nama_10_gdp) and (ert_bil_eur_a) and the United Nations Statistics Division (National Accounts Main Aggregates Database)

China and India had the highest GDP growth between 2006 and 2016

Figure 2 shows the real rate of change (based on price adjusted data) of GDP in the latest year for which data are available (2016 compared with 2015) as well as the 10 year annual average rate of change between 2006 and 2016; it should be remembered that the financial and economic crisis occurred during this 10 year period. The lowest 10 year rates of change were generally recorded in developed economies such as Japan, the EU-28, the United States and Canada, as well as in Russia, while the highest growth rates were recorded in several Asian economies, most notably in India and China. Analysing the rate of change for 2016 compared with 2015, three G20 members stand out, as Brazil, Argentina and Russia recorded a contraction in their economic output in 2016. The annual growth rate in 2016 for the world was 2.4 %, with the EU-28 recording slightly slower growth (2.0 %).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (nama_10_gdp) and the United Nations Statistics Division (National Accounts Main Aggregates Database)

Source: Eurostat (ert_bil_eur_a) and the World Bank (World Development Indicators)

In broad terms, members with relatively low GNI per inhabitant recorded relatively high economic growth over the 10 years from 2006 to 2016; this was most notably the case in India and Indonesia (note the rate of change covers the period from 2010-2016). By contrast, members with relatively high GNI per inhabitant at the start of the period under consideration recorded fairly low levels of economic growth; this was most notably the case in the EU-28, Canada and Japan. The main exceptions to this pattern are clustered towards the bottom left corner of Figure 3, with relatively low growth and relatively low levels of GNI per inhabitant — in this group are South Africa, Mexico, Argentina, Brazil and Russia.

General government finances

The financial and economic crisis of 2008 and 2009 resulted in considerable media exposure for government finance indicators. The importance of the general government sector — in other words all levels of government, from central to the most local level — in the economy may be measured in terms of general government revenue and expenditure (which is often presented in relation to GDP). Subtracting expenditure from revenue results in a basic measure of the government surplus/deficit (public balance), providing information on government borrowing/lending for a particular year; in other words, borrowing to finance a deficit or lending made possible by a surplus. General government debt (often referred to as national debt or public debt) refers to the consolidated stock of debt (external obligations) at the end of the year for government and public sector agencies. These external obligations are the debt or outstanding (unpaid) financial liabilities arising from past borrowing.

The sum of general government revenue and expenditure in relation to GDP peaked among the G20 members in 2016 at 91.05 % in the EU-28 (in the euro area it was higher still, at 93.7 %), followed by 79.8 % in Canada and 77.2 % in Argentina. The lowest sum of these ratios was in Indonesia (31.2 % of GDP). Note that the data for Mexico, Saudi Arabia and South Korea relate only to the expenditure and revenue of some levels of public administration as opposed to all levels.

South Korea was the only G20 member with a government surplus in 2016

Most G20 members had a government deficit in 2016; only South Korea recorded a surplus as can be seen from the difference between revenue and expenditure as shown in Figure 4 and also directly from the deficit data shown in Figure 5.

(% of GDP)

Source: Eurostat (gov_10a_main) and the International Monetary Fund (World Economic Outlook database)

(% of GDP)

Source: Eurostat (gov_10dd_edpt1) and the International Monetary Fund (World Economic Outlook database)

Relative to GDP, Saudi Arabia moved from the largest government surplus in 2006 among the G20 members to the largest government deficit in 2016

Comparing data for 2006 with 2016, South Korea increased its government surplus relative to GDP, while Saudi Arabia moved from having the largest surplus (20.8 % of GDP) in 2006 to the largest deficit (17.2 % of GDP) in 2016, reflecting a large fall in revenues, in part related to changes in oil prices. Indonesia, Canada, Australia, South Africa, Argentina and Russia also moved from surpluses in 2006 to deficits in 2016. All other G20 members had deficits in both years and in all cases the deficits in 2016 were larger relative to GDP than they had been in 2006, although the differences were relatively small for the EU-28 and India.

Japan and the United States recorded the largest increases in government debt between 2006 and 2016 and had the largest levels of debt relative to GDP in 2016

Japan had by far the highest government debt relative to GDP, both in 2006 and 2016: in 2006, Japanese government debt was 184.3 % of GDP while by 2016 this had expanded to 239.3 % (see Figure 6). Between 2006 and 2016 the United States joined Japan with a level of government debt that was higher than GDP, as its ratio moved from 64.2 % to 107.1 %. These two increases, 55.0 points for Japan and 42.9 points for the United States, were the largest increases in the government debt to GDP ratios among the G20 members.

(% of GDP)

Source: Eurostat (gov_10dd_edpt1) and the International Monetary Fund (World Economic Outlook database)

Canada (92.4 %) and the EU-28 (83.2 %) had the next highest levels of government debt relative to GDP in 2016 and both of their ratios also increased between 2006 and 2016. In fact, only five G20 members recorded lower ratios of government debt to GDP in 2016 than they had in 2006: India, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, Argentina and Turkey. In 2016, the lowest ratios of government debt to GDP were reported in Russia and Saudi Arabia, both below 20.0 % of GDP.

Balance of payments

Trade in goods and services normally accounts for the largest share of credits and debits in the current account of the balance of payments. Figure 7 shows the relative importance of these two items in 2017, with exports reflecting balance of payments credits and imports reflecting the level of debits.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (bop_eu6_q) and the International Monetary Fund (Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Statistics)

In terms of exports, the service oriented economies of India (2016 data), the United States (2016 data) and the EU-28 can be clearly seen, with services accounting for more than 30.0 % of exports: in all other G20 members the services share of total exports was below the world average of 23.6 %. Services contributed less than 10.0 % of all exports that originated from China (2016 data), Saudi Arabia (2016 data) and Mexico.

Turning to imports, services accounted for a share above the world average (23.6 %) in Saudi Arabia, Brazil, the EU-28, Argentina, Russia and Japan (all 2016 data except for the EU-28 and Brazil). As such, the EU-28 was the only G20 member where the relative importance of trade in services was above the world average for exports and for imports. Services represented less than 10.0 % of total imports into Turkey and Mexico in 2017, the lowest shares among the G20 members.

South Korea recorded the largest current account surplus relative to GDP in 2016

Among the G20 members, the largest current account surplus in 2016 in relative terms was recorded by South Korea, where this ratio peaked at 7.0 % of GDP (see Figure 8). The largest current account deficit in relative terms was recorded by Saudi Arabia at 4.3 % of GDP.

(% of GDP)

Source: Eurostat (bop_eu6_q) and (nama_10_gdp) and the International Monetary Fund (World Economic Outlook database)

The current account balances of Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Indonesia and Saudi Arabia moved from surpluses to deficits between 2006 and 2016, while the EU-28 moved from a deficit to a surplus. When expressed in relation to GDP, the deficits of Australia, India, South Africa, Turkey and the United States narrowed during the period under consideration, while in Mexico the deficit expanded. In South Korea, the current account surplus relative to GDP expanded while the surpluses of China, Japan and Russia narrowed. However, by far the largest change was observed in Saudi Arabia, as its current account balance moved from a surplus of 26.3 % of GDP in 2006 to a deficit of 4.3 % in 2016.

Foreign direct investment

Foreign direct investment (FDI) is characterised by investment in new foreign plant/offices, or by the purchase of existing assets that belong to a foreign enterprise. FDI differs from portfolio investment as it is made with the purpose of having a lasting interest, by acquiring control or an effective voice in the management of the direct investment enterprise.

The largest difference between inflows and outflows of FDI relative to GDP in 2016 were recorded in Australia and Brazil

Among the G20 members, FDI outflows exceeded FDI inflows in 2016 in Japan, Canada, South Korea, China, South Africa and Saudi Arabia (see Figure 9). The largest difference between inflows and outflows relative to GDP were recorded in Australia and Brazil, where inflows exceeded outflows by 3.5-3.6 points. Relative to GDP, the highest inflows of FDI were recorded by Brazil, Australia and Mexico, while outflows of FDI relative to GDP were highest from Canada and Japan. Outflows from Indonesia were negative in 2016, indicating that the amount of disinvestment of previous outflows of investment from Indonesia outweighed new outward investment from Indonesia.

(% of GDP)

Source: Eurostat (bop_fdi6_ind) and the World Bank (World Development Indicators)

The largest difference between inward and outward stocks of FDI relative to GDP in 2016 was recorded in Mexico

Figures 10 and 11 provide information concerning FDI stocks, in other words the value of all foreign direct investment assets, not just the flows during the previous year. Canada, South Africa and the EU-28 had by far the highest levels of outward stocks relative to the size of their economies in 2016, all in excess of half of their GDP. Canada also had the highest level of inward stocks relative to GDP and was one of only two G20 members — the other being Mexico (2015 data) — where inward stocks were valued at more than half of GDP; these figures are influenced at least in part by their proximity to the United States which was a major investor.

The lowest levels of outward stocks relative to GDP were held by Argentina, India, Indonesia and Turkey, all less than 10.0 % of GDP, while the lowest levels of inward stocks were in Japan (3.9 % of GDP), which is often characterised as a relatively closed economy. Five G20 members had outward stocks of FDI that outweighed their inward stocks: Japan, Canada, South Africa, the EU-28 and South Korea. Inward and outward stocks were nearly balanced in the United States with outward stocks slightly higher. The G20 members with the highest ratios of net inward stocks of FDI (greater levels of inward rather than outward stocks) relative to GDP included Brazil, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia and Mexico (2015 data).

(% of GDP)

Source: Eurostat (bop_fdi6_ind) and the OECD (FDI stocks)

Consumer prices, interest and exchange rates

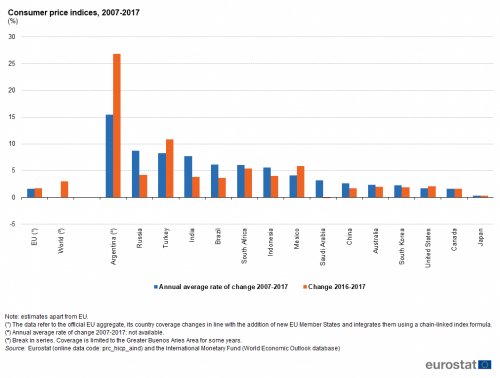

The latest annual rate of change in consumer price indices — between 2016 and 2017 — is presented in Figure 12 along with the 10 year annual average rate of change between 2007 and 2017. Consumer price indices indicate the change over time in the prices of consumer goods and services acquired, used or paid for by households. They aim to cover the whole set of goods and services consumed within the territory of a country by the population.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (prc_hicp_aind) and the International Monetary Fund (World Economic Outlook database)

The worldwide inflation rate in 2017 was 3.0 %, slightly higher than the 2.8 % rate that was reported in 2015 and 2016 and also slightly higher than the inflation rate had been in 2009 (at the height of the financial and economic crisis), but otherwise lower than in all other years since the beginning of the time series in 1980.

Argentina had the highest inflation rate among G20 members in 2017

In 2017, rates of change for consumer prices ranged from very slight deflation (a change of -0.2 %) in Saudi Arabia to inflation of less than 3.0 % in about half of the G20 members. Prices increased within the range of 3.7 % to 5.9 % in Brazil, India, Indonesia, Russia, South Africa and Mexico, while much higher inflation rates were reported for Turkey (10.9 %) and Argentina (26.9 %).

Average price developments over a 10 year period indicate that the high inflation rate in Argentina for 2017 was representative of a more sustained period of high price increases, with annual inflation averaging 15.4 % between 2007 and 2017. The next highest annual average inflation rates were a little more than half the rate recorded in Argentina, as prices rose by an annual average of 8.7 % in Russia and 8.3 % in Turkey, followed by 7.7 % in India during the period from 2007 to 2017. By contrast, Japan had clearly the lowest annual average inflation rate among the G20 members between 2007 and 2017, just 0.3 %, with the next lowest rates in Canada, the EU-28 (both 1.6 %) and the United States (1.7 %).

The largest falls in interest rates between 2006 and 2016 were in the United States and the euro area

Lending interest rates varied greatly between the G20 members in 2016 and did so to a somewhat greater extent than they had done 10 years earlier. Historically low interest rates — below 1.0 % — were recorded in the euro area and the United Kingdom (2014 data), while the latest lending interest rate in Japan was 1.0 %. Elsewhere, rates ranged from 2.7 % in Canada to 11.9 % in Indonesia, with the rates in Argentina (31.2 %) and Brazil (52.1 %) exceeding this range. In all but two of the G20 members for which data are available (see Figure 13), interest rates were lower in 2016 than they had been in 2006: in Argentina, rates increased by 22.6 points over this period, while in Brazil they increased by 1.3 points. The largest percentage point falls in interest rates between 2006 and 2016 were was in the euro area (down 4.3 points) and the United States (down 4.4 points).

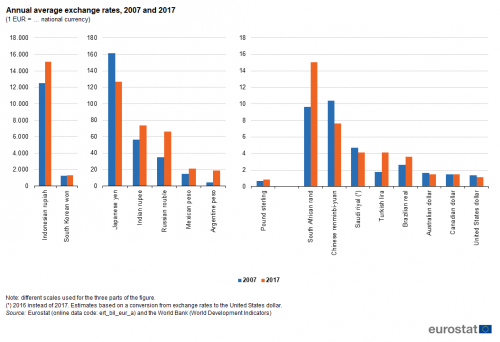

(1 EUR = … national currency)

Source: Eurostat (ert_bil_eur_a) and the World Bank (World Development Indicators)

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

The statistical data in this article were extracted during April 2018.

The indicators are often compiled according to international — sometimes worldwide — standards, for example, UN standards for national accounts and the International Monetary Fund's (IMF) standards for balance of payments statistics. Although most data are based on international concepts and definitions there may be certain discrepancies in the methods used to compile the data.

EU and euro area data

Nearly all of the indicators presented for the EU and the euro area have been drawn from Eurobase, Eurostat’s online database. Eurobase is updated regularly, so there may be differences between data appearing in this article and data that is subsequently downloaded. Data concerning interest rates in the euro area have been taken from the European Central Bank (ECB).

G20 members from the rest of the world

For the 15 non-EU G20 members, the data presented have been compiled by a number of international organisations, namely the IMF, the OECD, the United Nations Statistics Division and the World Bank. For some of the indicators shown a range of international statistical sources are available, each with their own policies and practices concerning data management (for example, concerning data validation, correction of errors, estimation of missing data, and frequency of updating). In general, attempts have been made to use only one source for each indicator in order to provide a comparable dataset for the members.

Context

An analysis of economic performance and developments can be carried out using a wide range of statistics, covering areas such as national accounts, government finance statistics, exchange rates and interest rates, consumer prices, and the balance of payments. These indicators are also used in the design, implementation and monitoring of economic policies.

GDP is the most commonly used economic indicator and it provides a measure of the size of an economy. It is the sum of the gross value added of all resident institutional units (‘domestic’ production) engaged in production, plus any taxes, and minus any subsidies, on products not included in the value of their outputs. It is also equal to i) the sum of the final uses of goods and services (all uses except intermediate consumption), minus the value of imports of goods and services; ii) the sum of primary incomes distributed by resident producer units. By contrast, GNI is the sum of gross primary incomes receivable by residents, in other words, GDP less income payable to non-residents plus income receivable from non-residents (‘national’ concept).

GDP per inhabitant is often used as a broad measure of living standards, although there are a number of international statistical initiatives to provide alternative and more inclusive measures (such as GDP and beyond).

A volume measure of GDP is intended to allow comparisons of economic developments over time, as the impact of price developments (inflation) has been removed. The use of a time series of a volume measure of GDP shows the ‘real’ change in GDP. Equally, international comparisons can be facilitated when indicators are converted from national currencies into a common currency using PPPs rather than market exchange rates. PPPs reflect price level differences between countries: in this article a number of indicators are presented in United States dollars (USD) having been converted using PPPs.

Direct access to

- [[Economy_and_finance|All articles on the economy and finance

- All articles on non-EU countries

- Other articles from The EU in the world

- The EU in the world 2018

- Sustainable Development in the European Union — Monitoring report on progress towards the SDGs in an EU context

- Smarter, greener, more inclusive ? Indicators to support the Europe 2020 strategy — 2017 edition

- Globalisation patterns in EU trade and investment

- 40 years of EU-ASEAN cooperation — 2017 edition

- Key figures on the enlargement countries — 2017 edition

- Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM) — A statistical portrait — 2016 edition

- The European Union and the African Union — 2016 edition

- Euro-Mediterranean statistics — 2015 edition

- The European Union and the BRIC countries

- The European Union and the Republic of Korea — 2012

- Main GDP aggregates (nama_10_ma)

- GDP and main components (output, expenditure and income) (nama_10_gdp)

- Balance of payments statistics and International investment positions (BPM6) (bop_q6)

- European Union and euro area balance of payments - quarterly data (BPM6) (bop_eu6_q)

- European Union direct investments (BPM6) (bop_fdi6)

- EU direct investments indicators in % of GDP, impact indicators and rate of return on direct investment (BPM6) (bop_fdi6_ind)

- Exchange rates (ert), see:

- Bilateral exchange rates (ert_bil)

- Euro/ECU exchange rates (ert_bil_eur)

- Euro/ECU exchange rates - annual data (ert_bil_eur_a)

- Euro/ECU exchange rates (ert_bil_eur)

- Government finance statistics (EDP and ESA2010) (gov_gfs10)

- Annual government finance statistics (gov_10a)

- Government revenue, expenditure and main aggregates (gov_10a_main)

- Government deficit and debt (gov_10dd)

- Government deficit/surplus, debt and associated data (gov_10dd_edpt1)

- HICP (2015 = 100) - annual data (average index and rate of change) (prc_hicp_aind)

- European Central Bank

- International Monetary Fund IMF

- United Nations Statistics Division

- The World Bank

Notes

- ↑ China is not shown in Figure 3 as the average annual real rate of change is not available.