Archive:Quality of life indicators - education

Data extracted in May 2018.

Planned update: May 2019.

In 2017, nearly one third (31.4 %) of the population aged 25-64 years in the EU had a tertiary level of educational attainment.

Across the EU, more than 9 in 10 (91.0 %) three year-olds were in early childhood education in 2016.

A majority (57 %) of the EU’s population aged 16-74 years had at least a basic level of digital literacy in 2017.

Proportion of the population aged 25-64 years who have a high level of educational attainment, 2017

Highlights

This article is part of a Eurostat online publication that focuses on Quality of life indicators, providing recent statistics for the European Union (EU). The publication presents a detailed view of various dimensions that can form the basis for a more profound analysis of the quality of life, complementing gross domestic product (GDP) which has traditionally been used to provide a general overview of economic and social developments. The focus of this article is the fourth dimension — education — of the nine quality of life indicators that form part of a framework, endorsed by an expert group on quality of life indicators. Broadly speaking, education refers to any act or experience that has a formative effect on an individual’s mind, character, or physical ability. Education is the process by which society — through schools, colleges, universities and other institutions — deliberately transmits its cultural heritage and its accumulated knowledge, values and skills to each generation.

Full article

Education in the context of quality of life=

In knowledge-based economies, education underpins economic growth, as it is the main driver of technological innovation and high productivity. Moreover, as a means to transmit knowledge through generations, education is the basis of human civilisation and has a major impact on the quality of life of individuals. A lack of skills and competencies limits access to the labour market and economic prosperity, increases the risk of social exclusion and poverty, and may hinder a full participation in civic and political affairs. Education enhances people’s understanding of the world they live in, and hence the perception of their ability to influence it. From a statistical perspective, education is a complex and challenging subject, sometimes difficult to measure. Eurostat's publication Statistical approaches to the measurement of skills — 2016 edition quotes a definition of human capital from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development as 'the knowledge, skills, competencies and other attributes embodied in individuals that are employed in the creation of individual, social and economic well-being'. It goes on to describe skills as 'the ability to apply knowledge and use know-how to complete tasks and solve problems'. The most common approach used for measuring skills is the indirect approach, where qualifications are used to measure skills supply. These data only certify skills developed in specific education programmes and do not cover skills developed through other means, such as on-the-job training or participation in social activities. One of the difficulties in statistically assessing educational outcomes is the complexity of measuring soft skills, acquired by individuals through social interaction, as well as the knowledge attained outside of the formal educational system (for example, through reading as a leisure pursuit or cultural activities). Moreover, the quality of formal qualifications (such as tertiary education degrees) is not always of the same level, especially when making comparisons across time or between and within countries. Furthermore, data on educational attainment relate to achievements at a specific point in time, which become less representative of current skill levels as time passes. It is therefore important to complement information on formal education attainment and training with information on participation in non-formal educational activities and participation in lifelong learning. As such the overall level of education may be measured through data on formal education attainment and training, as well as statistics related to non-formal or informal educational activities (an increasingly important aspect of the educational process). As a complement, a direct approach to measuring skills can be followed, either through assessment or self-reporting of abilities. Examples are assessments from the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC)) and self-reported data concerning the command of foreign languages and the use of information technology.

Level of educational attainment

Higher levels of educational attainment are generally linked to better occupational prospects and higher income, hence having a positive effect on a person’s quality of life. People who have completed tertiary education improve their possibilities to secure a job: in the EU-28 the unemployment rate was higher for low levels of educational attainment and lower for high levels of educational attainment. Based on data on unemployment rates by educational attainment level, in the EU-28, people aged 15-74 years with a low level of education in 2017 were more than three times as likely to be unemployed (14.8 %) as those with a high level of education (4.5 %); the ratio between the unemployment rates for people with high and low levels of education was particularly high in the Czech Republic, Lithuania, Slovakia, Hungary and Bulgaria, while it was relatively low in Cyprus, Greece and Portugal. When interpreting education levels for the whole of the population, it should be borne in mind that this includes older generations who may have been raised in times when formal education systems were quite different, for example with shorter compulsory education periods. Equally, levels of educational attainment within national populations reflect not only the outcomes of local education systems but also the educational attainment of immigrants. Overall in the EU-28, almost half (46.1 %) of the population aged 25-64 in 2017 had a medium level of education (upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education; ISCED levels 3 and 4), with the remainder split between a larger share (31.4 %) with a high level of education (tertiary education; ISCED levels 5-8) and a smaller share (22.5 %) with a low level of education (at most lower secondary education; ISCED levels 0-2) — see Figure 1.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfs_9903)

The various education levels leading up to lower secondary education (mainly pre-primary, primary and lower secondary education) form the main part of compulsory schooling in most EU Member States. In five southern Member States, in 2017 more than a quarter of the population aged 25-64 years had completed at most lower secondary education: 27.1 % in Greece, 39.1 % in Italy, 40.9 % in Spain, 52.0 % in Portugal and 52.7 % in Malta. While southern Member States tended to occupy one end of the ranking, the Member States with the lowest shares of people with at most lower secondary education were, with the exception of Finland, all in eastern parts of the EU or the Baltic Member States: in Lithuania, the Czech Republic, Poland, Slovakia and Latvia, less than 1 in 10 of the population aged 25-64 were in this category, with the next lowest shares in Estonia, Finland and Slovenia. The reverse situation can be observed for the share of the population with a medium level of education, with the highest shares generally in eastern EU Member States — the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Poland, Romania, Croatia and Hungary all reporting shares of at least 60.0 % — and the lowest in southern Member States, below one quarter in Spain and Portugal. The EU Member States with the highest proportions of people aged 25-64 with a tertiary level of educational attainment in 2017 were mainly in western or northern Europe, although a high share was also observed in Cyprus: at least two fifths of the population had completed tertiary studies in Ireland, Finland, the United Kingdom, Cyprus, Sweden, Lithuania and Belgium and this was also the case in the three EFTA countries shown in Figure 1. The lowest proportions — below one third — were in eastern and southern Member States, as well as in Germany and Austria; the lowest proportions of all were in Italy and Romania where less than one fifth of the population had completed tertiary studies, and this was also the case in the candidate country Turkey. Figure 2 focuses on the proportion of people aged 25-64 with a tertiary level of educational attainment, showing how this changed between 2007 and 2017. In the EU-28, this share increased 7.9 percentage points, from less than a quarter (23.5 %) to close to one third (31.4 %). The smallest and largest increases were in two western EU Member States that had relatively low shares in 2017: in Germany the share increased by 4.3 points from 24.3 % in 2007 to 28.6 % in 2017 while in Austria it increased 15.1 points from 17.3 % in 2007 to 32.4 % in 2017. However, it should be noted that there is a break in series for all of the data presented in Figure 2 as a new version of the classification of education (ISCED 2011) was introduced from the 2014 reference year, replacing the previous edition (ISCED 1997).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfs_9903)

Literacy

In this context, literacy is defined as the ability to understand, evaluate, use and engage with written text to participate in society, achieve one’s goals, and develop one’s knowledge and potential. Note that literacy refers exclusively to reading; it does not involve understanding spoken language, nor speaking or writing. Given the growing importance of digital devices and applications as a means of generating, accessing and storing text, the reading of digital texts is increasingly viewed as an integral part of literacy. The results of the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies are represented on a 500-point scale, with proficiency levels for individuals defined by particular ranges: 0-175 points is below level 1; 176-225 points is level 1; 226-275 points is level 2; 276-325 points is level 3; 326 or more points are levels 4 and 5. Figure 3 shows the results of surveys conducted mainly in 2011 or 2012 for the population aged 16-65 years. The three southern EU Member States for which data are available [1] — Italy, Spain and Greece — are grouped at the lower end of this ranking, with average literacy scores between 250 and 254 points. Two of the three Nordic Member States are near the top of the ranking, with Finland recording an average of 288 points, the highest among the Member States, and Sweden an average of 279 points, the third highest; Denmark’s average of 271 was towards the top of the middle third of the ranking. Otherwise, there was no clear regional pattern. For example, among the western Member States, the Netherlands recorded the second highest average (284 points) of all Member States, while France (262 points) recorded one of the lowest averages. Equally, among the eastern Member States, the Czech Republic and Slovakia recorded quite high averages (both 274 points), placing them in the top third of the ranking of Member States, while Slovenia recorded the lowest average (256 points) aside from in the southern Member States.

(Scale from 0 to 500)

Source: Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), OECD

Turning to the two non-member countries shown in Figure 3, Norway recorded a high average (278), in line with neighbouring Sweden, while Turkey recorded an average literacy (227) far below that in any of the EU Member States. There was no clear pattern to gender differences in adult literacy among the EU Member States. In Denmark, France, Italy and Slovakia the average scores were the same for men and women, while in six Member States the average was higher for women and in eight it was higher for men. In Poland and Greece the average scores were 5-6 points higher for women, while in Spain, Germany and the Netherlands the average scores were 5-6 points higher for men. In Turkey there was a larger gender difference, with the average score for men 11 points higher than for women; note that in Turkey, according to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, in 2015 the average time that people aged 25 years and over had spent in school was 9.0 years for men and 7.2 years for women.

Early childhood education

Early childhood is the stage where education can most effectively influence the development of children and help reverse disadvantage. Early childhood education is typically designed with a holistic approach to support children’s early cognitive, physical, social and emotional development and introduce young children to organised instruction outside of the family context. Importantly, it comprises an intentional education component (and not just care). Early childhood education is made up of two parts: early childhood educational development, designed for children up to two years of age; pre-primary education, designed for children from the age of three years to the start of primary education. A number of factors concerning pre-primary education have been linked to higher performance later during education, including the length of attendance of pre-primary education, smaller pupil-to-teacher ratios in pre-primary education, and higher public expenditure per child at the pre‑primary level. As such, enrolling pupils in good quality early childhood education may mitigate social inequalities and promote better overall student outcomes. Across the EU-28 as a whole, more than 9 in 10 (91.0 %) three year-olds were in early childhood education in 2016, with marginally higher ratios for girls (91.2 %) than for boys (90.8 %). In half the EU Member States at least four fifths of three year-olds were in early childhood education, with this share falling below 70 % in Cyprus, Luxembourg and Slovakia, below 60 % in Croatia and Ireland, and as low as 19.5 % in Greece. The highest ratios of enrolments of three year-olds in early childhood education were observed in the United Kingdom (100.0 %), France (99.4 %) and Belgium (98.0 %). Most western and northern EU Member States reported relatively high ratios, the exceptions being Lithuania, Austria, Finland, Luxembourg and Ireland. Eastern Member States generally reported relatively low ratios, although Hungary and Slovenia had ratios over 80.0 %. For the southern Member States there was no clear pattern as this ratio was high in Spain, Italy and Malta (all over 90.0 %), close to four fifths (79.9 %) in Portugal, but low in Cyprus and especially Greece. Among the EFTA countries, the shares of three year-olds in early childhood education in Iceland and Norway were high in 2016, in line with the ratios for most northern EU Member States, but the ratio was exceptionally low (2.5 %) in Switzerland where most children start compulsory education around the age of four or five years old. Among the four candidate countries for which data are available, the ratios were all relatively low, the highest being 50.0 % in Montenegro and the lowest 9.0 % in Turkey.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (educ_uoe_enrp07), (educ_uoe_enrp02) and (demo_pjan)

As can be seen from Figure 4, enrolment rates in early childhood education for three year-olds in 2016 were slightly higher for girls than for boys in most EU Member States, although the differences were often small. The ratio was at least 1.0 points higher for girls than for boys in Germany, Hungary, France, Croatia, Romania and Poland, and this gender gap peaked at 1.9 points higher in Austria. Among the eight Member States where the ratio was higher for boys than for girls, the gaps between the sexes were greatest in Slovenia (1.6 points), Italy (1.8 points) and the Netherlands (2.3 points). Among the non-member countries shown in the figure, a large gender gap was observed in Montenegro (2015 data; where the ratio was 2.5 points higher for boys than for girls).

Early leavers

Figure 1 presented information on the distribution of the population according to their level of educational attainment. The main influence on this is the age at which young people leave formal education, whether at the end of compulsory education, after secondary school (which normally but not always finishes at a later age than compulsory education), or after undertaking post-secondary education. The EU-28 has set a target to reduce the rate of early leavers from education and training below 10.0 % by 2020. The term early leavers generally refers to persons aged 18 to 24 years who had finished no more than a lower secondary education and were not involved in further education or training; their number can be expressed as a percentage of the total population aged 18 to 24 years. In setting the 2020 headline target, the EU identified early leaving from education and training as an obstacle to economic growth and employment, since on one hand it hampers productivity and competitiveness and on the other fuels poverty and social exclusion. As well as the overall headline target of 10.0 % for the EU-28, all but one (the United Kingdom) of the EU Member States set a national target, taking account of their particular circumstances. The EU-28 average rate of early leavers in 2017 was 10.6 %, just above the headline target of 10.0 %. There were 10 EU Member States which reported rates above the headline target, ranging from just above the target in Germany, the United Kingdom and Estonia, to more than 8.0 points above it in Romania, Spain and Malta. The challenge of reducing the rate of early leavers below national targets remains high in several EU Member States, as can be seen in Figure 5. The three Member States with the highest rates in 2017, along with Slovakia, were also those whose latest rates were furthest from their national targets: in Malta the 2017 rate was 8.6 points above the national target, with a gap of 6.8 points in Romania and 3.3 points in Spain and Slovakia. Half of the Member States reported early leaver rates in 2017 that were below their national targets, with the largest gap in this direction recorded in Greece, where the rate was 6.0 % in 2017, some 4.0 points below its 10.0 % national target.

(% of the population aged 18-24 years)

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfse_14)

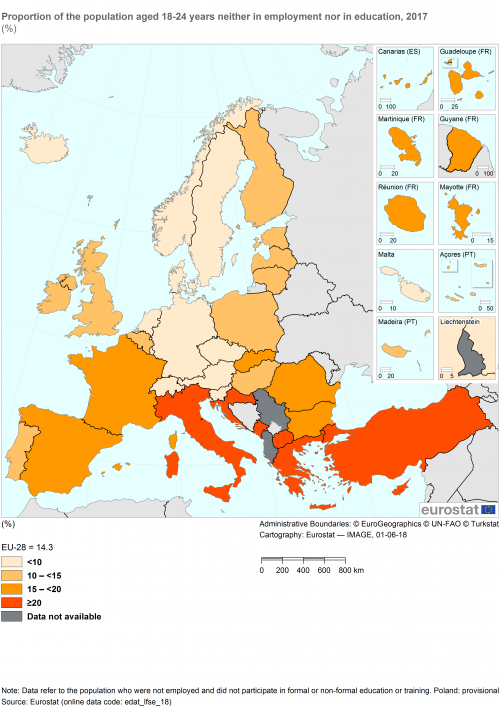

NEET: young people neither in employment nor in education and training

Some young people (aged 18-24 years) in the EU-28 are neither in employment nor in education or training a situation referred to as NEET. Long periods of absence from the labour market and the failure to acquire knowledge and occupational skills have been shown to undermine the future prospects of young people. The NEET indicator shows the share of young persons aged 18 to 24 years who were not employed and were not involved in further education or training. In 2017, 14.3 % of people aged between 18 and 24 years in the EU-28 were in this category. This situation was particularly common (over 15.0 %) in nine EU Member States, mostly situated in southern and eastern parts of the EU, but also including France (see Map 1). The highest shares — in all cases where more than one in five young people were neither in employment nor in education and training — were in Italy (25.7 %), Cyprus (22.7 %), Greece (21.4 %) and Croatia (20.2 %). However, not all southern and eastern Member States reported high NEET shares, as Malta (8.5 %), the Czech Republic (8.3 %) and Slovenia (8.0 %; the second lowest share among all EU Member States) were among the nine Member States where less than 1 in 10 young people were NEETs.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (edat_lfse_18)

High shares of NEETs were also observed in the three candidate countries shown in Map 1, while in the three EFTA countries for which data are available the share of young people neither in employment nor in education or training was consistently less than 8.0 %, with the shares in Norway (6.3 %) and Iceland (4.1 %) below the rate of 5.3 % in the Netherlands, which was the lowest among all of the EU Member States.

Lifelong learning

For many people, education continues beyond the end of their initial time spent in education (at school or higher education). Employability largely depends on the skills that people acquire throughout their professional and private lives. In this sense, lifelong learning has become a necessity in a competitive job market, as the needs of enterprises continuously develop, together with the technologies and techniques adopted by them. The term lifelong learning encompasses all learning activities undertaken throughout life for personal or professional reasons, after the age at which most people have usually finished their initial education. Through participation in learning activities people can improve their knowledge, skills and competences and so potentially enhance their careers as well as their quality of life. It is worth clarifying that lifelong learning statistics cover formal and non-formal guided education and training, but exclude self-learning activities. For example, evening courses are included as lifelong learning, whereas reading a history book, or visiting a science museum, although conceptually belonging to the concept of lifelong learning, are not included. The target population of Eurostat’s lifelong learning statistics is all members of private households aged between 25 and 64 years. Data are collected through the EU labour force survey (LFS). The indicator on participation shown in Figure 6 identifies the proportion of the target population reporting that they received education or training in the four weeks preceding the survey. Data from 2017 show that Sweden, Finland and Denmark have notably higher rates of participation in lifelong learning programmes than other EU Member States. More than one in four people in these Member States participated in such learning activities whereas in all other Member States the share was below one fifth, and the EU-28 average was 10.9 %. Among the EFTA countries, Switzerland (31.2 %) reported a share of its adult population participating in lifelong learning that was higher than in any of the EU Member States, while Iceland and Norway also reported relatively high rates. By contrast, participation in lifelong learning was below 5.0 % in Greece and five eastern Member States — Poland, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Croatia and Romania — as well as in two of the three candidate countries for which data are available. The lowest participation rate among the EU Member States was 2.7 % in Romania. People who have attained a tertiary level of education are more likely to continue studying than those who have completed at most lower secondary education: this was the case in all EU Member States as well as all non-member countries shown in Figure 6. In the EU-28, 18.6 % of the population aged 25 to 64 years having a high level of education in 2017 participated in lifelong learning programmes, compared with 4.3 % of people having a low level of education, a difference of 14.3 points. Particularly large differences were observed in France (22.1 points) and Finland (21.2 points), as well as in Austria, Luxembourg, Malta, Estonia, Sweden and Slovenia (all in the range of 18.5-20.0 points). Unsurprisingly, much smaller gaps were observed in some of the Member States with the lowest overall levels of participation in lifelong learning, such as Croatia (3.9 points). The enormously different participation rates for lifelong learning between the Member States can be illustrated by comparing the situation in Sweden with many other Member States. In 2017, 20.5 % of people with a low level of education in Sweden reported that they had recently participated in lifelong learning; despite this being only just over half the rate for people with a high level of education in Sweden, it was higher than the participation rate for people with a high level of education in 18 of the other EU Member States.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (trng_lfs_02)

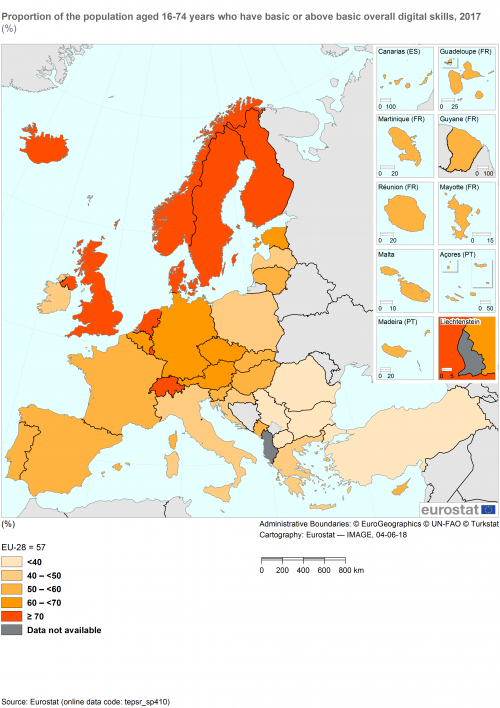

Computer and language skills

The ability to use a computer and the command of a foreign language are among the most important competencies in modern economies, not only for the job market but also to take advantage of education, information and cultural opportunities in our increasingly digital and globalised societies. Concerning digital skills, four skill levels are identified, ranging from no skills, through low and basic skills to above basic skills. These skill levels are determined based on activities concerning four domains, namely information skills, communication skills, problem-solving skills and software skills. For each of these domains several activities are identified and, depending on the number of these that a respondent declares having done, combined in some cases with their complexity, a respondent is assigned to one of the four skill levels for each domain; to be considered as having basic overall skills, respondents need to have at least basic skill levels in each of these four domains while to be considered as having above basic overall skills, respondents need to have above basic skill levels for all four domains. Close to three fifths (57 %) of people aged 16-74 years in the EU-28 reported that they had basic or above basic (hereafter referred to as at least basic) overall digital skills. Two EU Member States, Bulgaria and Romania, reported that 29 % of their populations had at least basic digital skills, considerably lower than in any other EU Member State and also lower than in the candidate countries shown in Map 2, where the share ranged from 32 % to 39 %, except in Montenegro where it reached 50 %. The share of the population with at least basic digital skills ranged from 40 % to less than 50 % in Croatia, Italy, Poland, Greece, Latvia and Ireland. Elsewhere in the EU, a majority of the population aged 16-74 years had at least basic digital skills, with the highest shares, above 70 % in the three Nordic Member States (Denmark, Finland and Sweden) as well as several western Member States, namely the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and Luxembourg: the last of these was the only Member State to report a share over four fifths, reaching 85 %. Equally, the three EFTA countries for which data are available reported high overall levels of at least basic digital skills (all above 70 %), notably in Iceland where the same share (85 %) was reached as in Luxembourg.

Source: Eurostat (tepsr_sp410)

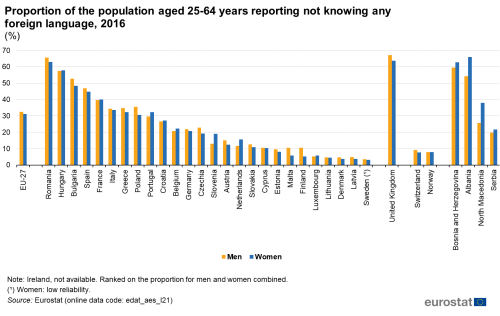

Within the 28 EU Member States there are currently 24 official languages, while the EU is home to over 60 indigenous, regional or minority languages, for example Basque and Saami. In most EU Member States an ability to communicate in foreign languages has become increasingly important, not only as a means of communication, but also to facilitate mobility, whether for leisure, study, work or other reasons. One of the EU’s multilingualism goals is for all people to speak two languages in addition to their mother tongue. The analysis presented in Figure 7 is based on the proportion of the population aged 25-64 years that did not speak any foreign language. In 2016, this was the case for just over one third (35.3 %) of the EU-28 population, with a relatively small gender gap as a slightly higher share of men (36.0 %) than women (34.7 %) did not speak any foreign language. In four EU Member States — the United Kingdom, Romania, Hungary and Bulgaria — a majority of the population do not speak a foreign language, while this was also the case for 45.8 % of the population in Spain. Elsewhere in the EU, the share of the population not knowing any foreign language was under two fifths, and was below one tenth in Malta and Luxembourg as well as the Baltic and Nordic Member States. In the two EFTA countries shown in Figure 7 less than one tenth did not speak a foreign language, while among the candidate countries the shares ranged from one fifth in Serbia to around three fifths in Albania and in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In most EU Member States, the gender gap concerning the proportion of the population that did not speak any foreign language resulted from a higher proportion among men than among women. In Finland, the proportion of women not speaking a foreign language was 5.3 points lower than that for men, while in Poland, Malta and Bulgaria this gap was between 4.0 and 5.0 points. The reverse situation was observed in Slovenia, the Benelux countries, Portugal, Croatia, Hungary and France, as a higher proportion of women than men did not speak a foreign language: this gap was largest in Slovenia (6.1 points) and the Netherlands (4.1 points).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (edat_aes_l21)

In all four candidate countries for which data are available, the proportion of men not speaking a foreign language was lower than the proportion of women, with gender gaps exceeding 10.0 points in Albania and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia.

Conclusions

In 2017, close to one third (31.4 %) of the EU-28 population aged 25-64 years had a tertiary level of educational attainment, while almost half (46.1 %) had completed upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education. The proportion of people aged 25-64 with a tertiary level of educational attainment increased in all EU Member States between 2007 and 2017. Among the 18 EU Member States for which data are available, average adult literacy scores were lower in the southern Member States than elsewhere in the EU, while they were highest in Finland, the Netherlands and Sweden. There was no clear pattern among the Member States concerning gender differences in adult literacy, however in the candidate country Turkey there was a notably higher level of literacy among men than women. Across the EU-28 as a whole, more than 9 in 10 (91.0 %) three year-olds were in early childhood education in 2016, with marginally higher ratios for girls (91.2 %) than for boys (90.8 %). Most western and northern EU Member States reported relatively high ratios, while the eastern Member States generally reported relatively low ratios; for the southern Member States there was no clear pattern as the share of three year-olds in early childhood education was high in Spain, Italy and Malta, but low in Cyprus and Greece. Enrolment rates in early childhood education for three year-olds in 2016 were slightly higher for girls than for boys in most EU Member States, although the differences were often small. Reducing the rate of early leavers from education and training remains a challenge for several EU Member States, notably in Spain, Malta, Romania and Slovakia, each of which recorded an early leavers’ rate in 2017 that was well above their 2020 national target. Equally, in 2017 the proportion of young people (aged 18-24 years) who were neither in employment nor in education and training (NEET) exceeded 15.0 % in several Member States in southern and eastern parts of the EU as well as in France, while the average rate for the EU-28 as a whole was 14.3 %. In 2017, the active participation of adults in lifelong learning activities was 10.9 % in the EU-28 among the population aged 25-64 years. Lifelong learning was considerably more common among people with a high level of educational attainment than it was among people with a low level of attainment. A majority of the EU-28’s population aged 16-74 years had at least a basic level of digital literacy in 2017. There is however a digital divide, between northern and north-western EU Member States on one hand and some other parts of the EU on the other, particularly Bulgaria and Romania. As well as having relatively high digital skills, in 2016 the Nordic Member States also reported some of the lowest proportions of people aged 25-64 not speaking any foreign language, along with the Baltic Member States, Luxembourg and Malta. Just over one third (35.3 %) of the EU-28 population in this age group did not speak a foreign language.

Source data for graphs and maps

Data sources

In the context of quality of life, education refers to: acquired competences and skills; the continued participation in lifelong learning activities; aspects related to access to education. Competences and skills are measured through data on educational attainment of the population (provided by the labour force survey (LFS)) as well as early school leavers (provided by education and training statistics). These are complemented by measures on self-reported and assessed skills: self-reported foreign language skills are available from education and training statistics, self-reported digital skills from a survey on information and communication technology (ICT) usage in households, and assessed literacy levels are currently available through the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies. Concerning the acquisition or not of new skills, the indicator of participation in early childhood education is available from education and training statistics, while the LFS provides the data for the proportion of the population neither in employment nor in education and for participation in lifelong learning.

Context

Education affects the quality of life of individuals in many ways. People with limited skills and competencies tend to have worse job opportunities and worse economic prospects, while early school leavers face higher risks of social exclusion and are less likely to participate in civic life. But beyond pragmatic considerations, education is in itself of value to our societies, since it allows people to understand the world they live in better. Education has an important place in EU policy as two headline targets of the overarching Europe 2020 strategy are related to education: at least 40 % of 30-34 year-olds should have completed tertiary education, and drop-out rates from education and training should be less than 10% by 2020. Furthermore, the strategic framework for European cooperation in education and training (ET 2020) set objectives to make lifelong learning and mobility a reality, as well as improving the quality and efficiency of education and training. Another important European strategy promotes multilingualism with a view to strengthening social cohesion and intercultural dialogue within the EU.

Direct access to

- Quality of life indicators (online publication)

- Digital skills (t_isoc_sk)

- ICT users (t_isoc_sku)

- Individuals who have basic or above basic overall digital skills by sex (tepsr_sp410)

- ICT users (t_isoc_sku)

- Participation in education and training (educ_part)

- Pupils and students - enrolments (educ_uoe_enr)

- Early childhood education and primary education (educ_uoe_enrp)

- Adult learning (trng)

- Main indicators on adult participation in learning - LFS data from 1992 onwards (trng_lfs_4w0)

- Participation in education and training (last 4 weeks) - population aged 18+ (trng_lfs_4w1)

- Main indicators on adult participation in learning - LFS data from 1992 onwards (trng_lfs_4w0)

- Pupils and students - enrolments (educ_uoe_enr)

- Education and training outcomes (educ_outc)

- Educational attainment level (edat)

- Population by educational attainment level (edat1)

- Transition from education to work (edatt)

- Young people by educational and labour status (incl. neither in employment nor in education and training - NEET) (edatt0)

- Early leavers from education and training (edatt1)

- Educational attainment level (edat)

- Languages (educ_lang)

- Self-reported language skills (educ_lang_00)

- Number of foreign languages known (edat_aes_l2)

- Self-reported language skills (educ_lang_00)

Notes

- ↑ For this indicator, data are not available (were not collected) for 10 EU Member States.