Archive:Household accounts at regional level

- Data from March 2009, most recent data: Further Eurostat information, Main tables and Database.

One of the primary aims of regional statistics is to measure the wealth of regions. This is of particular relevance as a basis for policy measures which aim to provide support for less well-off regions.

The indicator most frequently used to measure the wealth of a region is regional gross domestic product (GDP), usually expressed in purchasing power standard (PPS) per inhabitant to make the data comparable between regions of differing size and purchasing power.

GDP is the total value of goods and services produced in a region by the people employed in that region, minus the necessary inputs. However, owing to a multitude of interregional flows and state interventions, the GDP generated in a given region often does not tally with the income actually available to the inhabitants of the region. This article takes a look at household incomes in the regions of the European Union (EU) and how much of this is available after income distribution mechanisms have had an effect.

Main statistical findings

Private household income

In market economies with state redistribution mechanisms, a distinction is made between two stages of income distribution.

The primary distribution of income shows the income of private households generated directly from market transactions, i.e. the purchase and sale of factors of production and goods. These factors include, in particular, the compensation of employees - i.e. the income from the sale of labour as a factor of production. Private households can also receive income on assets, particularly interest, dividends from equity shares and rents. Then there is also income from operating surpluses and self-employment. Interest and rents payable are recorded as negative items for households in the initial distribution stage. The balance of all these transactions is known as the primary income of private households.

Primary income is the point of departure for the secondary distribution of income, which means the state redistribution mechanism. All social benefits and transfers other than in kind (monetary transfers) are now added to primary income. From their income, households have to pay taxes on income and wealth, pay their social contributions and effect transfers. The balance remaining after these transactions have been carried out is called the disposable income of private households.

For a comprehensive analysis of household income, a decision must first be made about the unit in which data are to be expressed if comparisons between regions are to be meaningful.

For the purposes of making comparisons between regions, regional GDP is generally expressed in PPS so that meaningful volume comparisons can be made. The same process should, therefore, be applied to the income parameters of private households. These are, therefore, converted with specific purchasing power standards for final consumption expenditure called purchasing power consumption standards (PPCS).

2006 results

Primary income

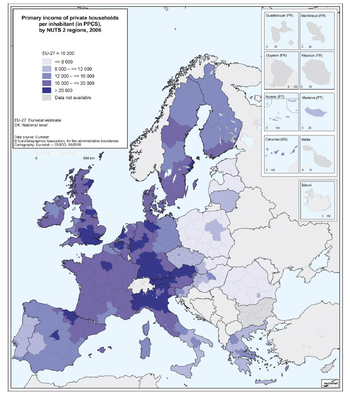

Map 1 gives an overview of primary income in the NUTS 2 regions of the 23 countries examined here. Centres of wealth are clearly evident in southern England, Paris, northern Italy, Austria, Madrid and north-east Spain, Flanders, the western Netherlands, Stockholm, Nordrhein-Westfalen, Hessen, Baden-Württemberg and Bayern. Also, there is a clear north–south divide in Italy and a west–east divide in Germany. In contrast, in France wealth distribution is relatively uniform between regions. The United Kingdom, too, has a north–south divide, although less marked than the divides in Italy and Germany.

In the new Member States, it is mainly the capital regions that have relatively high income levels, particularly Bratislava and Praha, where income levels are close to the EU average. Közép-Magyarország (Budapest), Mazowieckie (Warszawa) and București-Ilfov also have relatively high income levels. The primary income of private households is over half the EU average in all the other Czech regions, in two other Hungarian regions, and in Slovenia and Lithuania, while in all the other regions of the new Member States, it is below that level.

The regional values range from 3 197 PPCS per inhabitant in north-eastern Romania to 35 116 PPCS in the UK region of Inner London. The 10 regions with the highest income per inhabitant include five regions in the UK, three in Germany and one each in France and Belgium. This clear concentration of regions with the highest incomes in the United Kingdom and Germany is also evident when the ranking is extended to the top 30 regions. This group contains 11 German and seven UK regions, along with three each in Italy and Austria, two in Belgium and one each in France, the Netherlands, Spain and Sweden.

It is no surprise that the 30 regions at the tail end of the ranking are all located in the new Member States; the list contains 15 of the 16 Polish regions, seven of the eight Romanian regions, four of the seven Hungarian regions and two of the four Slovakian regions, together with Estonia and Latvia.

In 2006, the highest and lowest primary incomes in the EU regions differed by a factor of 11.0. Five years earlier, in 2001, this factor had been 10.4. There was therefore a slight increase in the gap between the opposite ends of this distribution over the period 2001–06.

Disposable income

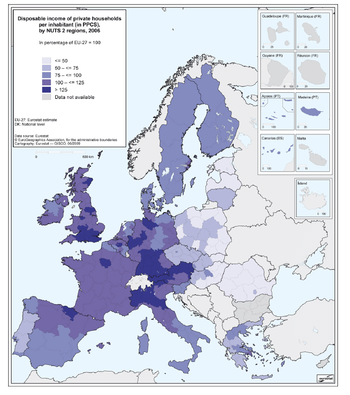

A comparison of primary income with disposable income (see Map 2) shows the levelling influence of state intervention. This particularly increases the relative income level in some regions of Italy and Spain, in the west of the United Kingdom and in parts of eastern Germany and Greece. Similar effects can be observed in the new Member States, particularly in Hungary, Romania, Slovakia and Poland. However, the levelling out of private income levels in the new Member States is generally less pronounced than in the 'older' EU-15 Member States.

In spite of state redistribution and other transfers, most capital regions maintain their prominent position with the highest disposable income for the country in question.

Of the 10 regions with the highest disposable income per inhabitant, five are in the United Kingdom, four in Germany, and one in France. The region with the highest disposable income in the new Member States is Bratislavský kraj with 12 309 PPCS per inhabitant, followed by Praha with 12 241 PPCS.

A clear concentration of regions is also evident when the ranking is extended to the top 30 regions. This group contains 11 German and nine UK regions, along with four regions in Austria, three in Italy and one each in Belgium, France and Spain.

The tail end of the distribution is very similar to the ranking for primary income. The bottom 30 regions include 13 Polish and seven Romanian regions, four in Hungary, two in Slovakia and one in Greece, plus the three Baltic States.

The regional values range from 3 610 PPCS per inhabitant in north-east Romania to 25 403 PPCS in the UK region of Inner London. State activity and other transfers significantly reduce the difference between the highest and lowest regional values in the 23 countries examined with here from a factor of around 11.0 to 7.0.

In contrast to primary income, there is a significant trend in disposable income towards a narrowing of the range in regional values: between 2001 and 2006 the difference between the highest and lowest values fell from a factor of 8.5 to 7.0.

It can thus be concluded overall that measurable regional convergence between 2001 and 2006 occurred only with regard to the level of disposable income affected by state intervention. This was not the case with regard to the primary income generated from market transactions.

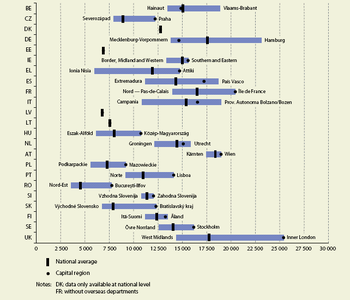

The regional spread in disposable income within the individual countries is naturally much lower than for the EU as a whole, but varies considerably from one country to another. Figure 1 gives an overview of the range of disposable income per inhabitant between the regions with the highest and the lowest value for each country. It can be seen that, with a factor of over 2, the regional disparities are greatest in Romania and Greece. This means that the disposable income per inhabitant in the region of București-Ilfov is more than twice as high as in north-eastern Romania. With factors of around 1.8, Slovakia, the United Kingdom, Hungary and Italy also have wide regional variations. For Spain, Poland and Germany, the highest value is about two-thirds higher than the respective lowest value. The regional concentration is in general higher in the Member States which have joined the Union since 2004 than in the EU-15.

Of the newer Member States, Slovenia, with 11 %, has the smallest spread between the highest and lowest values and, thus, comes very close to Austria, which has the lowest regional income disparities. Ireland, Finland, Sweden and the Netherlands also have only moderate regional disparities, with the highest values ranging between 10 % and 28 % greater than the lowest values.

Figure 1 also shows that the capital cities of 13 of the 18 countries with more than one NUTS 2 region also have the highest income values. This group includes four of the six largest new Member States.

Capital region bonus

The economic dominance of the capital regions is also evident when their income values are compared with the national averages. In four countries (the Czech Republic, Romania, Slovakia and the United Kingdom), the capital cities exceed the national values by more than a third. Only in Belgium and Germany are the values lower than the national average.

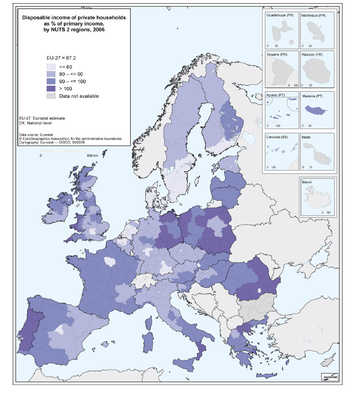

To assess the economic situation in individual regions, it is important to know not just the levels of primary and disposable income but also their relationship to each other. Map 3 shows this quotient, which gives an idea of the effects of state activity and of other transfer payments. On average, disposable income in the EU amounts to 87.2 % of primary income. In 2001, this figure had been 87.0 %, so over this five-year period the scale of state intervention and other transfers hardly changed. In general, the EU-15 Member States have somewhat lower values than the new Member States.

On closer inspection, substantial differences can be seen between the regions of the Member States. Disposable income in the capital cities and other prosperous regions of the EU-15 is generally less than 80 % of primary income. Correspondingly higher percentages can be observed in the less affluent areas, in particular on the southern and south-western peripheries of the EU, in the west of the United Kingdom and in eastern Germany.

This is because in regions with relatively high income levels, a larger proportion of primary income is transferred to the state in the form of taxes. At the same time, state social benefits amount to less than in regions with relatively low income levels.

The regional redistribution of wealth is generally less significant in the new Member States than in the EU-15. For the capital regions the values are between 80 % and 90 % and are almost without exception at the bottom end of the ranking within each country. This shows that incomes in these regions require much less support through social benefits than elsewhere. The difference between the capital region and the rest of the country is particularly large in Romania and Slovakia, at around 15 percentage points.

In the 23 EU Member States analyzed here, there is a total of 30 regions in which disposable income exceeds primary income. This applies in particular to 12 of the 16 regions in Poland and four of the eight regions in Romania. In the EU-15, the most noticeable instances are six regions of eastern Germany, three regions in Portugal and two in the United Kingdom.

When interpreting these results, however, it should be borne in mind that it is not just monetary social benefits from the state which may cause disposable income to exceed primary income. Other transfer payments (e.g. transfers from people temporarily working in other regions) can play a role in some cases.

Dynamic development on the edges of the Union

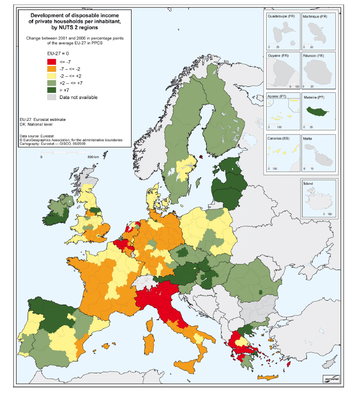

The focus finally turns to an overview of medium-term trends in the regions compared with the EU average. Map 4 uses a five-year comparison to show how disposable income per inhabitant (in PPCS) in the NUTS 2 regions changed between 2001 and 2006 compared to the EU average.

The map shows, first of all, powerful dynamic processes in action on the edges of the Union, particularly in Spain and Ireland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary and the Baltic States.

On the other hand, below-average trends in income are apparent in Belgium, Germany, France and especially Italy, where even regions with only average levels of income were affected. The changes range from +16.4 percentage points for Bucureşti-Ilfov (Romania) to -14.4 percentage points in Liguria (Italy).

Despite clear evidence of an overall catching-up process in the new Member States, the same positive trend is not found everywhere. In seven of Poland’s 16 regions incomes increased by only up to 1.5 percentage points compared with the EU-27 average. The figures for Romania, on the other hand, are very encouraging. With an increase of 16.4 percentage points, the București — Ilfov region achieved the highest relative improvement of all regions, with even the Nord-Est region (the region with the lowest income in the whole EU) catching up by 4.8 percentage points on average income growth in the EU. The structural problem nevertheless remains that in all the new Member States the wealth gap between the capital city and the less prosperous parts of the country has widened further.

On the whole, the trend between 2001 and 2006 resulted in a slight flattening of the upper edge of the regional income distribution band, caused in particular by substantial relative falls in regions with high levels of income. At the same time, all of the 10 regions at the tail end of the ranking have caught up considerably on the EU average.

Conclusion

The regional distribution of disposable household income differs from that of regional GDP in a large number of NUTS 2 regions, in particular because unlike regional GDP, the figures for the income of private households are not affected by commuter flows. In some cases, other transfer payments and flows of other types of income received by private households from outside their region also play a substantial role. In addition, state intervention in the form of monetary social transfers and the levying of direct taxes tends to level out the disparities between regions.

Taken together, state intervention and other influences bring the spread of disposable income between the most prosperous and the economically weakest regions to a factor of about 7.0, whereas the two extreme values of primary income per inhabitant differ by a factor of 11.0. The flattening out of regional income distribution desired by most countries is, therefore, being achieved.

The income level of private households in the newer Member States continues to be far below that in the EU-15; in only a small number of capital regions are income values more than three-quarters of the EU average.

An analysis over the five-year period 2001–06 shows that incomes in many regions of the new Member States are catching up only very slowly. This applies in particular to certain regions of Poland. In Romania, in contrast, a strong catching-up process has taken hold — a development which, happily, extends beyond the capital region of București-Ilfov.

For disposable income, there is a measurable trend towards a narrowing of the spread in regional values: between 2001 and 2006 the difference between the highest and lowest values fell from a factor of 8.5 to 7.0, while for primary income the differences between regions increased from a factor of 10.4 to 11.0.

With regard to the availability of data concerning income, it may be said that the comprehensiveness of the data and the length of the time series have gradually improved. Once a complete data set is available, data on the income of private households could be taken into account, alongside GDP statistics, when decisions are taken on regional policy measures.

Data sources and availability

Eurostat has had regional data on the income categories of private households for a number of years. The data are collected for the purposes of the regional accounts at NUTS level 2.

There are still no data available at NUTS 2 level for the following regions: Bulgaria, France’s overseas departments, Cyprus, Luxembourg and Malta. For Denmark and Slovenia, only national data are available. For Italy, regional figures were available only up to and including 2004, but national figures were available for 2005. The regional figures for 2005 were, therefore, estimated using the regional structure from 2004.

The text in this article, therefore, relates to only 23 Member States, or 251 NUTS 2 regions. Three of these 23 Member States consist of only one NUTS 2 region, namely Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Since the beginning of 2008, Denmark and Slovenia have consisted of five and two NUTS 2 regions, respectively, but they appear here only as single NUTS 1 regions, as no data are yet available for the newly defined NUTS 2 regions.

Owing to the limited availability of data, the EU values for the regional household accounts had to be estimated. For this purpose, it was assumed that the share of the missing Member States in household income for the EU as a whole was the same as for GDP. For the reference year 2005, this portion was 0.6 %.

Data that reached Eurostat after 8 April 2008 are not taken into account in this article.

Context

One drawback of regional GDP per inhabitant as an indicator of wealth is that a ‘place-of-work’ figure (the GDP produced in the region) is divided by a ‘place-of-residence’ figure (the population living in the region). This inconsistency is of relevance wherever there are net commuter flows — i.e. more or fewer people working in a region than living in it. The most obvious example is the Inner London region of the UK, which has by far the highest GDP per inhabitant in the EU. Yet this by no means translates into a correspondingly high income level for the inhabitants of the same region, as thousands of commuters travel to London every day to work but live in the neighbouring regions. Hamburg, Vienna, Luxembourg, Prague and Bratislava are other examples of this phenomenon.

Apart from commuter flows, other factors can also cause the regional distribution of actual income not to correspond to the distribution of GDP. These include, for example, income from rent, interest or dividends received by the residents of a certain region, but paid by residents of other regions.

This being the case, a more accurate picture of a region’s economic situation can be obtained only by adding the figures for net income accruing to private households.

Further Eurostat information

Publications

- Eurostat regional yearbook 2009 (available in English, French and German)

Main tables

- Regional economic accounts - ESA95 (t_reg_eco)

- Disposable income of private households, by NUTS 2 regions (tgs00026)

- Primary income of private households, by NUTS 2 regions (tgs00036)

Database

- Regional economic accounts - ESA95 (reg_eco)

- Household accounts - ESA95 (reg_ecohh)

- Allocation of primary income account of households at NUTS level 2 (reg_ehh2p)

- Secondary distribution of income account of households at NUTS level 2 (reg_ehh2s)

- Income of households at NUTS level 2 (reg_ehh2inc)

- Household accounts - ESA95 (reg_ecohh)