Archive:Enlargement countries - transport statistics

- Data extracted in September 2015. Most recent data: Further Eurostat information, Main tables and Database. Planned article update: September 2016.

This article is part of an online publication and provides information on a range of transport statistics for the EU enlargement countries, in other words the candidate countries and potential candidates. Montenegro, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Albania, Serbia and Turkey currently have candidate status, while Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo [1] are potential candidates.

The article provides information in relation to a range of transport statistics, including the length and density of transport networks, the motorisation rate and an analysis of freight transport.

(km)

Source: Eurostat (cpc_transp) and the Directorate-General for Mobility and Transport (EU transport in figures, available at: http://ec.europa.eu/transport/media/publications/index_en.htm)

Source: Eurostat (demo_r_d3area), (demo_pjan), (cpc_transp), (cpc_agmain) and (cpc_psdemo) and the Directorate-General for Mobility and Transport (EU transport in figures, available at: http://ec.europa.eu/transport/media/publications/index_en.htm)

(passenger cars per 1 000 inhabitants)

Source: Eurostat (demo_pjan) and (cpc_transp) and the Directorate-General for Mobility and Transport (EU transport in figures, available at: http://ec.europa.eu/transport/media/publications/index_en.htm)

Source: Eurostat (road_go_ta_tott), (rail_go_typeall), (mar_mg_aa_cwhd) and (cpc_transp)

(%, based on tonne-km)

Source: Eurostat (tran_hv_frmod) and (cpc_transp)

Main statistical findings

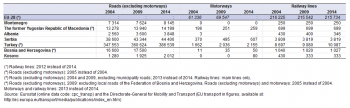

Transport networks

Most of the enlargement countries are relatively small in terms of their total area and population numbers; hence, it is perhaps unsurprising to find that they generally had relatively small motorway networks, in some cases less than 100 km in length (see Table 1). The main exception was the largest enlargement country, Turkey, where the motorway network was 2 155 km long in 2014. The motorway network in Turkey expanded between 2004 and 2014, as the length of Turkish motorways rose, on average, by 2.6 % per annum. The other enlargement countries reported faster expansions in relative terms, with annual increases of 2.8 % for the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, 5.1 % for Serbia and 16.3 % for Bosnia and Herzegovina (from 2005 to 2013).

Turkey also had the longest road network (other than motorways), at 387 thousand km in 2013, while there were almost 45 thousand km of road in Serbia in 2014, which was the second highest value.

There were 216 000 km of railway lines in the EU-28 in 2012, practically unchanged when compared with 2004.

The length of railway lines was also unchanged in Montenegro and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia between 2004 and 2014, while there was a very slight expansion in Serbia (an additional 10 km of railway line). The rail network in Turkey grew at a more rapid pace, with its length rising by 1390 km (note that the data for Turkey only cover main lines). By contrast, there was a modest reduction in the length of railway lines in Bosnia and Herzegovina (2004 to 2013), and much larger reductions in Albania and Kosovo.

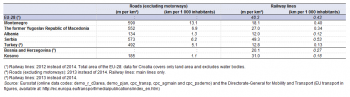

Relative to its population, Montenegro had the densest road network among enlargement countries

Table 2 provides alternative measures of the relative importance of transport networks, presenting the density of networks in relation to total area and numbers of inhabitants. Montenegro, Serbia and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia recorded the highest density of roads among the enlargement countries, with 590 m, 573 m and 552 m of road per square kilometre (km²) of total area in 2014. Using this measure, roads in Kosovo and Albania were spread more thinly across each territory; some 185 m and 134 m per km².

An alternative network density measure is one which uses the number of inhabitants as its denominator. On this basis, the road network in Montenegro was about twice as dense as in any other enlargement country, with an average of 13.1 kilometres (km) of road per 1 000 inhabitants in 2014. The road networks of Albania and Kosovo were again relatively sparse, using this measure, when compared with the remaining enlargement countries, with 1.3 km and 1.1 km of road per 1 000 inhabitants in 2014.

The rail network was particularly developed in Serbia and in Montenegro

Across the EU-28, the density of railway lines was generally quite high in western and central Europe and lower in peripheral (especially sparsely populated) regions. In 2012, the rail network density of the EU-28 averaged 48.3 m per km² or 0.43 km per 1 000 inhabitants.

Serbia had the highest rail network density among the enlargement countries, both in relation to its total area and number of inhabitants. While the former was only slightly higher (at 49.3 m per km² in 2014) than the EU-28 average, Serbia’s rail network density relative to population (0.53 km per 1 000 inhabitants) was clearly above the EU-28 average. Indeed, Serbia was the only enlargement country to report a rail network density that was higher than in the EU-28. By contrast, Turkey and Albania reported the lowest ratios for their rail networks, 12.8 m and 12.0 m per km² and 0.13 km and 0.12 km per 1 000 inhabitants in 2014; note that the data for Turkey refer only to main lines.

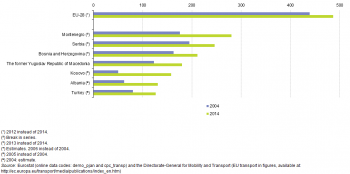

Motorisation rate

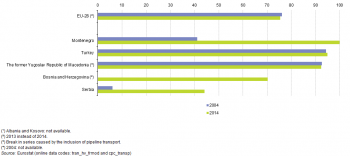

The principal mode of passenger transport in the EU is the passenger car, providing both flexibility and mobility for personal journeys. In the EU-28, there were an estimated 487 passenger cars per 1 000 inhabitants in 2012. This marked an increase of 11 % in car ownership (or 48 additional cars per 1 000 inhabitants) when compared with 2004 (see Figure 1).

Montenegro and Serbia had the highest motorisation rates among enlargement countries

The motorisation rate for the enlargement countries was considerably lower than in the EU-28. There were, on average, 280 passenger cars per 1 000 inhabitants in Montenegro in 2014 and 247 per 1 000 inhabitants in Serbia in 2013; these were the highest rates among the enlargement countries. By contrast, motorisation rates in Turkey, Albania and Kosovo were within the range of 127–158 passenger cars per 1 000 inhabitants.

During the 10-year period shown in Figure 1 there was faster growth in the motorisation rate in all of the enlargement countries than in the EU-28. Although Kosovo, Albania and Turkey recorded the lowest motorisation rates in 2014, along with Montenegro they also recorded the fastest expansion in car ownership between 2004 and 2014. The highest rate of change was recorded in Kosovo, where the motorisation rate trebled between 2005 and 2014.

Freight transport

The ability to move goods safely, quickly and cost-efficiently to markets is important for international trade, national distributive trades, and economic development. The rapid increase in global trade up to the onset of the financial and economic crisis and the deepening integration of the EU, alongside a range of economic practices (including the concentration of production in fewer sites to reap economies of scale, delocalisation, and just-in-time deliveries), may explain the relatively fast growth of freight transport.

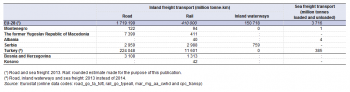

Within the EU-28, three quarters of all inland freight transport was by road in 2013, accounting for 1 720 billion tonne-kilometres (tkm). Rail was the second most common mode for transporting inland freight (an estimated 410 billion tkm in 2014), while the relative importance of inland waterways was much lower (151 billion tkm in 2014). The EU-28 also transported (inward and outward transport combined) 3.7 billion tonnes of sea freight in 2013 (see Table 3).

Inland freight transport in Serbia was split fairly evenly between road and rail, while there was also a relatively high share for inland waterways

The relative importance of rail freight transport was much higher in Serbia and in Montenegro, with slightly more goods transported by rail than by road in Serbia in 2014. Serbia also had a relatively high share of inland freight transport on inland waterways (essentially on the Danube).

There was generally a high propensity to make use of roads for inland freight transport in both the EU and the majority of the enlargement countries (see Figure 2). While the share of road transport in total inland freight transport was 75.4 % across the EU-28 in 2013, there was an even greater reliance on using roads to transport freight in Montenegro, Turkey and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, where 100.0 %, 94.9 % and 92.4 % of inland freight was moved by road in 2014. As noted above, there was a relatively high use made of rail and inland waterways for freight transport in Serbia and as a consequence Serbia had the lowest share of road freight transport among the enlargement countries (44.1 % in 2014). Nevertheless, between 2004 and 2012 the road freight share in Serbia increased each and every year to reach 44.8 %, since when the share stabilised. In Montenegro, the road freight share had reached 51.0 % by 2012 after which it jumped to 100 % in 2013 and 2014 as the use of inland rail freight stopped.

Turkey was the only enlargement country (subject to data availability) to record any notable movement of freight by sea, some 385 million tonnes in 2013: the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Serbia and Kosovo are landlocked; Bosnia and Herzegovina has only one coastal town and most of its sea freight passes through Croatian ports.

Data sources and availability

Data for the enlargement countries are collected for a wide range of indicators each year through a questionnaire that is sent by Eurostat to partner countries which have either the status of being candidate countries or potential candidates. A network of contacts in each country has been established for updating these questionnaires, generally within the national statistical offices, but potentially including representatives of other data-producing organisations (for example, central banks or government ministries). The statistics shown in this article are made available free-of-charge on Eurostat’s website, together with a wide range of other socio-economic indicators collected as part of this initiative.

For the EU-28, the development of passenger and freight transport statistics is based upon a draft of framework legislation and implementing legislation, generally organised according to the mode of transport under consideration.

Transport statistics are available with an annual frequency and generally begin in the early 1990s. The majority are based on movements in each reporting country, regardless of the nationality of the vehicle or vessel involved (the ‘territoriality principle’). For this reason, the measure of tonne-kilometres (tkm or tonne-km, in other words, one tonne of goods travelling a distance of one kilometre) is generally considered a more reliable measure when analysing freight transport statistics, as the simple use of tonnes entails a higher risk of double-counting, particularly for international transport. The modal split of inland freight transport is based on transportation by road, rail and inland waterways, and therefore excludes air, maritime and pipeline transport. It measures the share of each transport mode in total inland freight transport and is expressed in tonne-kilometres.

The weight of goods transported by rail and inland waterways is the gross-gross weight. This includes the total weight of the goods, all packaging, and the tare weight of the container, swap-body and pallets containing goods; in the case of rail freight transport, it also includes road goods vehicles that are carried by rail. By contrast, the weight measured for maritime and road freight transport is the gross weight (in other words, excluding the tare weight).

Tables in this article use the following notation:

| Value in italics | data value is forecasted, provisional or estimated and is therefore likely to change; |

| : | not available, confidential or unreliable value. |

| – | not applicable. |

Context

An efficient and well-functioning passenger and freight transport system is vital for EU enterprises and inhabitants. The EU’s transport policy aims to foster clean, safe and efficient travel throughout Europe, underpinning the internal market for goods (transferring them between their place of production and consumption) and the right of citizens to travel freely throughout the EU (for both work and pleasure).

Transport infrastructure and transport networks are fundamental for the smooth operation of the economy, for the mobility of persons and goods and for the economic, social and territorial cohesion of a country. In September 2014, the European Commission invited EU Member States to propose projects to use EUR 11.9 billion of EU funding to improve European transport connections. This was the first tranche of the new funding for transport to be made available and also marked the largest ever single amount of EU funding earmarked for transport infrastructure. For the period 2014–20, EUR 26 billion of financing has been foreseen for transport (around three times the EUR 8 billion during the period 2007–13), under the Connecting Europe Facility (CEF).

EU transport policy also seeks to ensure that passengers benefit from the same basic standards of treatment wherever they travel within the EU. With this in mind the EU legislates to protect passenger rights across the different modes of transport. Passengers already have a range of rights covering areas as diverse as: information about their journey; reservations and ticket prices; damages to their baggage; delays and cancellations; or difficulties encountered with package holidays.

While basic principles and institutional frameworks for producing statistics are already in place, the enlargement countries are expected to increase progressively the volume and quality of their data and to transmit these data to Eurostat in the context of the EU enlargement process. The EU standards in the field of statistics require the existence of a statistical infrastructure based on principles such as professional independence, impartiality, relevance, confidentiality of individual data and easy access to official statistics; they cover methodology, classifications and standards for production.

Eurostat has the responsibility to ensure that statistical production of the enlargement countries complies with the EU acquis in the field of statistics. To do so, Eurostat supports the national statistical offices and other producers of official statistics through a range of initiatives, such as pilot surveys, training courses, traineeships, study visits, workshops and seminars, and participation in meetings within the European statistical system (ESS). The ultimate goal is the provision of harmonised, high-quality data that conforms to European and international standards.

Additional information on statistical cooperation with the enlargement countries is provided here.

See also

- Enlargement countries — statistical overview — online publication

- Statistical cooperation — online publication

Further Eurostat information

Publications

- Basic figures on enlargement countries — 2015 edition

- Key figures on the enlargement countries — 2014 edition

- Key figures on the enlargement countries — 2013 edition

- Energy, transport and environment indicators — 2015 edition

Database

- Transport (cpc_tr)

- Candidate countries and potential candidates: transport (cpc_transp)

- Transport, see:

- Multimodal data (tran)

- Transport, volume and modal split (tran_hv)

- Railway transport (rail)

- Railway transport measurement — Goods (detailed data based on Directive 80/1177/EC or Regulation (EC) 91/2003) (rail_go)

- Road transport (road)

- Road transport infrastructure (road_if)

- Road freight transport measurement (road_go)

- Inland waterways transport (iww)

- Inland waterways transport measurement — goods (iww_go)

- Inland waterways transport measurement — goods — annual data (iww_go_a)

- Maritime transport (mar)

- Maritime transport — main annual results (mar_m)

Dedicated section

Methodology / Metadata

- Candidate countries and potential candidates (cpc) (ESMS metadata file — cpc_esms)

Source data for tables and figures (MS Excel)

External links

Notes

- ↑ This designation is without prejudice to positions on status, and is in line with UNSCR 1244 and the ICJ Opinion on the Kosovo Declaration of Independence.