Archive:Europe 2020 indicators - poverty and social exclusion

- Data from July 2013. Most recent data:Further Eurostat information, Main tables.

This article is part of a set of statistical articles based on the Eurostat publication Smarter, greener, more inclusive? - Indicators to support the Europe 2020 strategy. It provides recent statistics on poverty and social inclusion in the European Union (EU), key areas of the EU's Europe 2020 strategy.

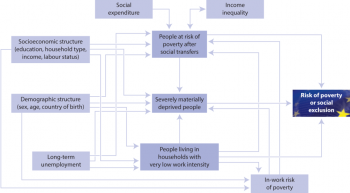

The analysis focuses on the indicator ‘people at risk of poverty or social exclusion’, itself consisting of three sub-indicators on monetary poverty, material deprivation and low work intensity, respectively. Additional contextual indicators present a broader picture and show the drivers behind changes, providing a breakdown by sex, age, educational attainment level, household type, country of birth and labour status and identifying the groups most at risk. Finally, factor factors reducing or increasing the risk of poverty and social exclusion are discussed: social protection expenditures and long-term unemployment (see the article on employment).

Europe 2020 strategy target on the risk of poverty and social exclusion

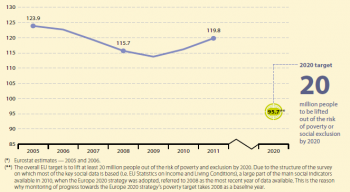

The Europe 2020 strategy has set the target of ‘promoting social inclusion, in particular through the reduction of poverty, by aiming to lift at least 20 million people out of the risk of poverty and exclusion’ by 2020 [1].

(Million people)

Source: Eurostat online data code (t2020_50)

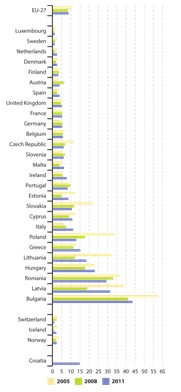

(% of population)

Source: Eurostat online data code (t2020_50)

(*) EU-27 data for 2005 are estimates; 2006 data (instead of 2005) for BG;2007 data (instead of 2005) for RO; break in series in 2008 for BG, FR, CY, LV, PL and in 2011 for LV.

(% of population)

Source: Eurostat online data code (t2020_50)

(*) EU-27 data for 2005 are estimates; 2006 data (instead of 2005) for BG; 2007 data (instead of 2005) for RO; break in series in 2008 for BG, FR, CY, LV, PL and in 2011 for LV.

(% of population)

Source: Eurostat online data code (ilc_peps01)

(*) Data for 2005 are estimates

Source: Eurostat online data code (ilc_peps01)

(*) Data for 2005 are estimates.

(% of population)

Source: Eurostat online data code (ilc_peps03)

(*) 2005 data for EU-27 are estimates, 2006 data for BG (instead of 2005); break in series in 2008 for FR, CY, LV, PL and in 2011 for LV.

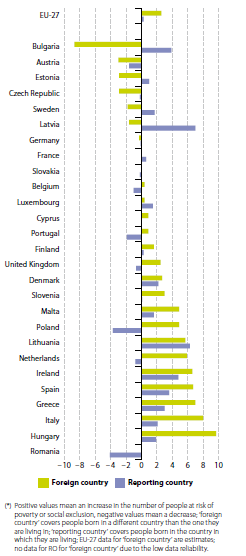

(percentage points)

Source: Eurostat online data code (ilc_peps06)

(% of population aged 18 and over)

Source: Eurostat online data code (ilc_peps04)

(*) Data for 2005 are estimates.

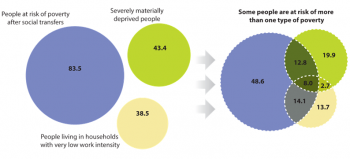

(Million people)

Source: Eurostat online data code (ilc_pees01), (t2020_50), (t2020_51), (t2020_52) and t2020_53}}

(*) People at risk of poverty or social exclusion: 119.8 million.

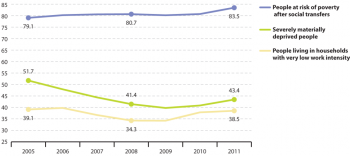

(% of population aged 18 and over)

Source: Eurostat online data code (t2020_51), (t2020_52) and (t2020_53)

(*) Data for 2005 and 2006 are estimates (all three sub-indicators); 2007 data for ‘People at risk of poverty after social transfers’ are estimates; 2009 data for ‘Severely materially deprived people’ are estimates.

(% of population)

Source: Eurostat online data code (t2020_52)

(*) EU-27 data for 2005 are estimates; 2007 data (instead of 2005) for RO and CH; break in series in 2008 for FR and CY, in 2010 for HR, and in 2011 for LV.

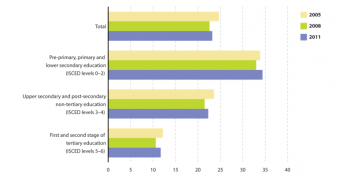

(%)

Source: Eurostat online data code (ilc_li02), (ilc_li03) and (ilc_li07)

(*) For education the population is restricted to those aged 18 years and over.

(%)

Source: Eurostat online data code (ilc_li02), (ilc_li10) and (spr_exp_sum))

(%)

Source: Eurostat online data code (ilc_di01)

(% of population)

Source: Eurostat online data code (t2020_53)

(%)

Source: Eurostat online data code (ilc_mddd11)

(%)

Source: Eurostat online data code (ilc_mddd13), (ilc_mddd14) and (ilc_mddd16)

(% of population)

Source: Eurostat online data code (ilc_mdes04), (ilc_mdes09) (ilc_mddd11)

(% of population aged 0 to 59)

Source: Eurostat online data code (t2020_51)

(% of population aged 18 and over)

Source: Eurostat online data code (ilc_li04)

(%)

Source: Eurostat online data code (tsdsc330)

(%)

Source: Eurostat online data code (ilc_iw01), (ilc_iw02) and (ilc_iw07)

Main statistical findings

How do poverty and social exclusion affect Europe?

The headline indicator ‘People at risk of poverty or social exclusion’ shows the number of people affected by at least one of three forms of poverty: monetary poverty, material deprivation or low work intensity. People can suffer from more than one dimension of poverty at once. To calculate the headline indicator people are counted only once even if they are present in more than one sub-indicator (for more details see p. 136).

As shown in Figure 2, the number of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion had been decreasing steadily before the economic crisis. The indicator reached its lowest level in 2009 with about 114 million people at risk of poverty or social exclusion in the EU. However, the number of affected people grew again in the following years. The serious impact of the economic crisis on Member States’ financial and labour markets was the most likely cause (see the ‘greener, more inclusive - employment Employment’ chapter).

Automatic stabilisers and other discretionary measures were used to help cushion the recession’s negative social effects. By 2011 almost 120 million people — about 24 % of the EU population¬ — were at risk of poverty or social exclusion. This means almost one in four people in the EU experienced at least one of the three forms of poverty or social exclusion.

The current economic situation poses a major challenge to policy makers trying to fight poverty and ensure social inclusion. The emphasis needs to shift from short-term measures to structural reforms in order to spur economic growth, promote high levels of employment (tackling in-work poverty), guarantee adequate social protection and access to quality services (such as healthcare, childcare, housing). Social policies alone cannot deliver on the Europe 2020 poverty target. This objective must be underpinned by other public policies in the economic, employment, tax and education fields [2].

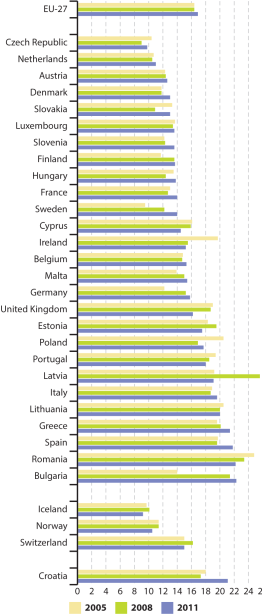

The number of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion has increased in most Member States

To meet the overall EU target on risk of poverty and social exclusion, Member States have set their own national targets [3] in their National Reform Programmes. As noted in the European Council conclusions from 17 June 2010 [4], Member States are free to set their own targets based on the most appropriate indicators for their circumstances and priorities. In most countries the target is expressed as an absolute number of people to be lifted out of the risk of poverty or social exclusion compared to the level in 2008. As mentioned earlier this base year is also used for the overall EU target [5].

Most countries have experienced an increase in the number of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion since 2008, widening the gap to their national targets. Poverty levels have improved in only a few countries. Germany and Romania had already reached their national targets by 2011. The other Member States remain some distance from their targets. These range from more than four million people in Italy to about 14 500 people in Malta.

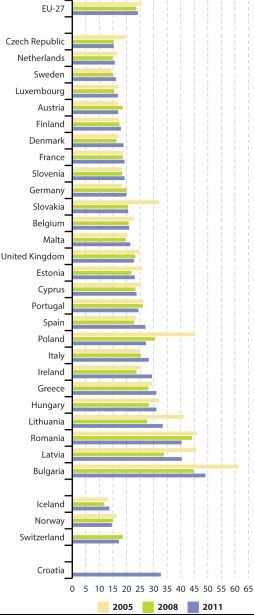

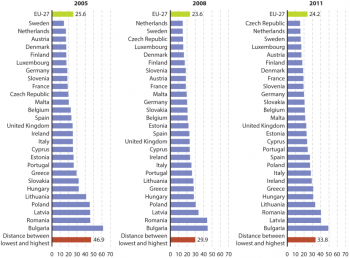

Overall, 24.2 % of people in the EU were at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2011. However, this conceals considerable variations among Member States in both the level and dynamics of this indicator (see Figure 3). In Bulgaria almost half of the population (49.1 %) was living at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2011. In the Czech Republic, the Netherlands and Sweden the rate was about three times lower.

In the EU as a whole, and in most Member States, the number of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion reached its lowest level in 2009 before growing again. During the time period 2005 to 2011 there were significant differences between Member States. Some countries have made clear progress in integrating their most vulnerable members into society. For example, Poland, Slovakia, the Czech Republic and Bulgaria reduced the number of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion by 20 % to 40 %. A number of countries have experienced less inclusive growth. In Ireland, Spain, Italy, Sweden and Denmark the proportion of the population at risk of poverty or social exclusion increased by 10 % to 20 %.

One reason for the disparity in poverty rates across the EU is the uneven impact of the economic crisis on Member States. Differences in the structure of labour markets, welfare systems, the fiscal position and fiscal consolidation measures have also played a role [6] (see the ‘greener, more inclusive - employment Employment’ chapter).

In this respect, a link between the average risk of poverty and social exclusion at EU level and the disparities across the EU can be observed: the higher the average percentage of people at risk in the EU as a whole, the higher the distance between the lowest and the highest percentage observed across the Member States (see Figure 4). This growing divergence of inequality and poverty levels between Member States has raised serious concern. In particular, a persistent widening of the gap in social exclusion levels could lead to a dangerous polarisation within the EU [7].

Which groups are at greater risk of poverty or social exclusion?

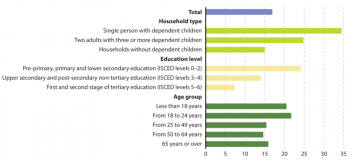

Compared with the EU average, some groups are at a higher risk of poverty and social exclusion. The most affected are women, young people, people living in single-parent households, lower educated people and migrants. EU policies aimed at reducing the number of people at risk therefore tend to focus on these groups. They call on Member States to define and implement measures to address their specific circumstances [8].

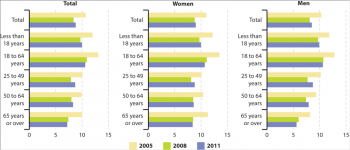

Women are more likely to live in poverty and social exclusion than men

In 2011, 25.3 % of women were at risk of poverty or social exclusion across the EU compared to 23.1 % of men, an EU-wide gender gap of 2.2 percentage points. Women were worse off in all countries except Estonia. The gaps were highest in Sweden, Cyprus and Slovenia at more than 3.7 percentage points. Estonia and Lithuania were the most egalitarian countries with gender gaps of less than or around 0.4 percentage points.

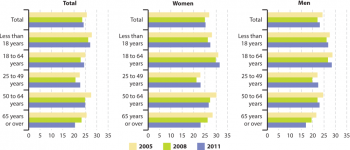

The disparities between women and men become more distinct when looking at individual age groups. Among men, the young aged 18 to 24 were most at risk (28.4 %) in 2011 compared with older people aged 65 or over (17.0 %). In contrast, women were more likely to be at risk in all age groups (see Figure 5). The risk of poverty or social exclusion was most unequal among the older groups aged 50 or over.

Young people aged 18 to 24 are more at risk

For both men and women, young people aged 18 to 24 are the most likely to be at risk of poverty or social exclusion. Almost 30 % were at risk in 2011 (28.4 % for men and 31.5 % for women). People in the age group less than 18 years were the next most at risk, at 27.1 %. Moreover, the situation for young people aged 18 to 24 has not improved compared to 2005. Although their risk of poverty or social exclusion had been falling until 2009, it climbed back in the following years to the level observed in 2005.

In contrast, older people aged 65 or over showed the lowest rates of 20.4 % (17.0 % for men and 23.1 % for women) in 2011. The rates of this group have also shown a steady decline over the period 2005 to 2010 (see Figure 5). As a result the age gap has widened over the past years. This indicates the burden of the financial crisis has fallen more heavily on those already belonging to the most vulnerable groups of society.

The widening of the gap between young people aged 18 to 24 and older people aged 65 or over is also observable for most Member States. Between 2008 and 2011, in almost all Member States, except for Sweden, Poland and Germany, the gap increased, in some cases massively. In Latvia, the age gap changed by about 36 percentage points. This was due to the number of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion rising by 11 percentage points among young people and falling by 25 percentage points among the elderly (see the ‘greener, more inclusive - employment Employment’ chapter).

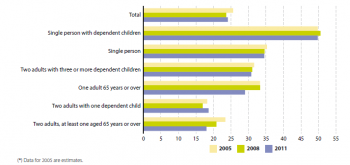

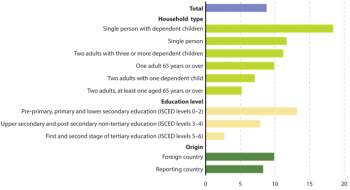

Single parents face the highest risk of poverty or social exclusion

About 50 % of single people with one or more dependent children were at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2011. This was double the average and higher than in any other household type or group analysed. Figure 6 shows that the situation for single parents at EU level has been stable since 2005. The group with the lowest poverty rate in 2011, and showing the most improvement since 2005, was households where at least one person was aged 65 years or over.

At the national level there were wide disparities among single parent households during the period 2005 to 2011. Between 2005 and 2008 the risk of poverty or social exclusion of single parent households decreased in most countries. Slovakia, Denmark, Poland, Estonia, Lithuania and the Netherlands experienced the biggest improvements, with decreases ranging between 18 and 10 percentage points. Changes in the at-risk rate were more diverse during 2008 to 2011. They ranged from a 16.1 percentage point decrease in Portugal to a 12.5 percentage point increase in Denmark. The biggest increases took place in Denmark, Latvia, Sweden, Bulgaria and France, while the biggest falls were in Portugal, Cyprus, Romania, Slovenia and Malta.

In contrast, for households with two adults with at least one aged 65 or over, the at-risk rate decreased in most countries. Hence the absence of children seems to lower the risk of poverty or social exclusion.

Migrants are worse off than people living in their home countries

People living in the EU but in a different country from where they were born had a 32.6 % risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2011. This is about 10 percentage points higher than for people living in their home countries. This ‘origin gap’ could be seen in most European countries in 2011, except Bulgaria. It was highest in Belgium, where the risk of poverty or social exclusion among migrants was 24.4 percentage points higher than for those born in the country. In 16 Member States, the risk of poverty or social exclusion among foreigners increased between 2008 and 2011 (see Figure 8). Hungary showed the highest increase of 9.7 percentage points. In contrast, in Bulgaria the risk decreased by 8.4 percentage points. This trend might be explained by the fact that migrants suffered the most from rising unemployment in the EU [9].

People with low educational attainment are three times more likely to be at risk

In 2011, 34.4 % of people with at most lower secondary educational attainment were at risk of poverty or social exclusion (see Figure 9). In comparison, only 11.7 % of people with tertiary education were in the same situation. This indicates that people with the lowest education levels were about three times more likely to be at risk than those with the highest education levels (also see the ‘greener, more inclusive - education Education’ chapter).

A similar situation could be seen in Member States such as Sweden, Slovenia, the Nether-lands, Luxembourg, Spain, Denmark, Hungary, Italy, Germany and Bulgaria. In these countries people with higher educational attainment were less affected by the rise in the poverty rate between 2008 and 2011. However, a better education did not necessarily protect everyone against the crisis. For example in Greece, Cyprus, Ireland and Lithuania the rate of poverty or social exclusion increased most among people with tertiary education.

The three dimensions of poverty

The 119.8 million people who were at risk of poverty or social exclusion in the EU in 2011 were affected by one or more dimensions of poverty (see Box 5.5).

As shown in Figure 10, monetary poverty was the most widespread form in 2011, with 83.5 million people living at risk of poverty after social transfers. This was followed by material deprivation, affecting 43.4 million people, and low work intensity, affecting 38.5 million people.

More than one-third affected by more than one dimension of poverty

About 38 million people, or almost 36 % of all people at risk of poverty or social exclusion, were affected by more than one dimension of poverty in 2011. Of these, 12.8 million people suffered from monetary poverty and material deprivation, 2.7 million were both materially deprived and living in households with very low work intensity, and 14.1 million were affected by low work intensity and monetary poverty. Another 8.0 million people were affected by all three forms (see Figure 10).

Divergent developments of the three forms of poverty

The three forms of poverty have developed in different ways over the past five years. Monetary poverty has not only been the most prevalent form, it has also shown the highest growth (see Figure 11). Since 2005 it has been increasing continuously. In contrast, the number of people living in deprived circumstances or in low-work-intensity households fell considerably over the period 2005 to 2008, by about 20 % and 12 % respectively. Growth in these two forms of poverty only started in 2009. This shows that improvements in the headline indicator between 2005 and 2009 (see Figure 2) can mainly be traced to the reduction in material deprivation and low work intensity. One possible reason for the divergence of monetary poverty on the one hand and material deprivation and low work intensity on the other is the different structure of the indicators (see Box 5.5). While monetary poverty is measured in relative terms, material deprivation and low work intensity are absolute measures (see Box 5.1). The relativity of monetary poverty means the at-risk rate may remain stable or even increase even if a country’s average or median disposable income increases. Absolute poverty measures, however, are expected to decrease during economic revivals.

Monetary poverty increased in over half of Member States

In 2011, 16.9 % of the EU population earned less than 60 % of their respective national median equivalised disposable income, the so-called ‘poverty threshold’. This represents a slight increase compared with 2008, when the risk-of-poverty rate was 16.4 %.

The increase did not take place in all countries (see Figure 12). Between 2005 and 2011 the number of people at risk of monetary poverty rose in 15 Member States and fell in the rest. In most countries this decrease took place between 2005 and 2008 and was halted or even reversed between 2008 and 2011 when the at-risk-of-poverty rate increased in most countries. The countries reporting the highest rates in 2011 were Bulgaria (22.3 %), Romania (22.2 %) and Spain (21.8 %). The best performing Member States for monetary poverty were the Czech Republic (9.8 %), the Netherlands (11.0 %) and Austria (12.6 %).

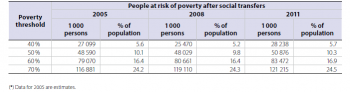

Impact of the poverty threshold

Monetary poverty is related to the disposable income after social transfers. It is reached when disposable income falls below a certain threshold. Hence, the number of people considered monetarily poor depends on the level at which the poverty threshold is set (see Table 5.1).

If the poverty threshold was set at 70 % of the national median disposable income, nearly one out of four people would be at risk of poverty. This holds for 2005, 2008 and 2011. If the threshold was set at 50 % or 40 %, then about 10 % or 5 % of the population would be at risk respectively. For poverty thresholds at 40 % and 50 %, the number of people at risk of poverty slightly decreased in 2008 compared to 2005. And for all of these four thresholds the number of people at risk of poverty is higher in 2011 than in 2005 and 2008.

Single parents, large families, low educated and young people most affected

Single parenthood bears the biggest risk of monetary poverty. One out of three households in this group tended to be affected in 2011. The number of children also influences the risk, with one out of four large family households being touched. Single-wage and part-time employment may also cause monetary poverty [10]. A lack of affordable childcare might prevent parents from fully participating in the labour market [11] (see ‘greener, more inclusive - employment Employment’ chapter).

The higher risk of poverty of households with children is reflected in the fact that young people face a greater risk of living in poverty (see Figure 13).

Children and young people (age groups up to 24 years old) remained vulnerable groups in 2011. One out of five was at risk of poverty. Compared with 2008, the number of poor people aged 65 years or over has fallen by 3.1 percentage points but the amount of poor young people has risen. Among those aged less than 18 years and those aged 18 to 24, the number of poor people increased by 0.5 and 1.8 percentage points respectively.

The most vulnerable age groups vary between Member States. Commission analyses point to the persistent gender pay gap and the higher presence of women in precarious employment as possible reasons. While in 2011 in Romania and Spain children were most at risk and in Denmark young people (aged 18 to 24) were most at risk, in Cyprus and Bulgaria the elderly were the most at risk. The risk of suffering from monetary poverty is slightly higher for women in most Member States [12].

As with poverty and social exclusion, a low level of education is a major risk factor for monetary poverty. While in 2011 about 7 % of people with higher education were affected by monetary poverty, almost 25 % of people with lower education were affected. This could also be related to the higher level of unemployment and in-work poverty among low-skilled workers (see ‘greener, more inclusive - employment Employment’ chapter).

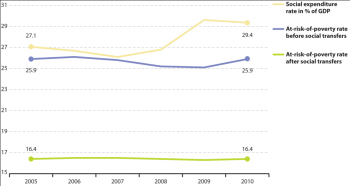

Social expenditure helped prevent more monetary poverty

To support the needs of people at risk of poverty, governments provide social security in the form of social transfers. The effectiveness of social provision can be evaluated by comparing the at-risk-of-poverty rate before and after social transfers and considering social policy expenditures (see Figure 14). The amount of money spent on social assistance is a good indicator of income support expenditure [13].

The at-risk-of-poverty rate before social transfers had been declining slightly until 2009 before increasing to 25.9 % in 2010. However, the at-risk-of-poverty rate after social transfers has remained stable at around 16 %. To hold the latter steady, social protection expenditure in absolute terms has increased continuously since 2005. In relation to GDP social protection expenditure fell slightly until 2007 while GDP grew. The fall in GDP during the crisis of 2008 and 2009 prompted an increase in the social expenditure rate to 29.4 % in 2010. This relative increase helped to prevent more people from suffering from monetary poverty. In comparison, the social expenditure rate tended to decline during periods of economic recovery.

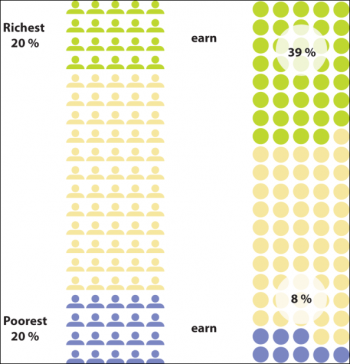

Inequality of income distribution remained stable

As with the number of people suffering from monetary poverty after social transfers, income inequality has also remained stable. To measure income inequality, the income quintile share ratio and the Gini coefficient [14] can be considered. Between 2008 and 2011, income inequality remained stable in the EU, with the richest 20 % of the population earning about five times more than the poorest 20 % (see Figure 15).

There are considerable differences among Member States in the income quintile share ratio. In 2011 Spain, Bulgaria, Greece, Lithuania and Portugal recorded the highest inequality in income distribution. The total income of the richest 20 % in these Member States was seven times (for Spain and Bulgaria) or six times (for Greece, Lithuania and Portugal) higher than the income of the poorest 20 %. On the other hand Slovenia and the EFTA countries Norway and Iceland had income quintile share ratios below 3.5.

The Gini coefficient for the EU was 30.7 in 2011, a level similar to previous years (a coefficient of 100 expresses perfect inequality and a coefficient of 0 expresses perfect equality). Income inequality according to the Gini coefficient was again lowest in Norway, Slovenia and Sweden, with coefficients of less than 25. On the other hand, in Latvia, Bulgaria, Portugal and Spain the index exceeded the EU average by more than four percentage points, indicating relatively high income inequality in these countries.

Material deprivation is the second most common form of poverty

Material deprivation covers issues relating to economic strain, durables and housing and environment of the dwellings. Severely materially deprived persons have living conditions greatly constrained by a lack of resources.

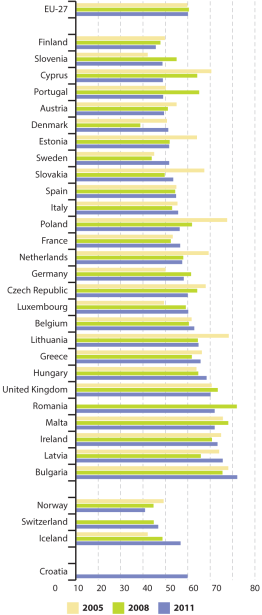

In 2011, 43.4 million people in the EU were living in conditions severely constrained by a lack of resources. This equalled 8.8 % of the total EU population or every eleventh person, making severe material deprivation the second most common form of poverty. The levels of severe material deprivation differed widely across the EU in 2011, from more than 40 % in Bulgaria to as low as 1.2 % in Luxembourg and Sweden (see Figure 16).

A combination of factors are likely to cause these persistent disparities between Member States. Differences in living standards, levels of development and social policies all play a part [15].

In a few Member States poor living conditions seem to be a much more serious problem than monetary poverty. For example, in Bulgaria the proportion of people living in severely deprived conditions was almost twice as high as the share living in monetary poverty. To a lesser extent, a similar situation could also be observed in Latvia, Romania and Hungary. On the other hand, in a number of countries with higher standards of living such as Sweden, Luxembourg and Denmark, monetary poverty rates appear high

Since 2005 the number of people living in severe material deprivation has remained stable or decreased slightly in countries with initially low rates below 5 % such as Sweden, Luxembourg, or the Netherlands. It has substantially fallen in countries with high rates of 30 % or more such as Bulgaria, Lithuania and Romania. The only Member State where it has significantly increased is Italy.

Since 2008, the number of materially deprived people has decreased in 11 countries. The most distinct improvements took place in Austria, Poland, Portugal and Romania. In the other 16 Member States, the number of people living in severe materially deprived circumstances grew between 2008 and 2011 with the highest increases in Italy, Spain and Greece.

Women and young people more affected

As is the case for the other indicators analysed in this chapter, women and people aged 18 to 24 were the most affected by material deprivation in 2011. Figure 17, illustrating the rates of materially deprived people among different age groups and by gender, shows age disparities were greater for men. Moreover men aged 65 years or over were better off than any other group in 2011.

Single parents, poorly educated and migrants were worse off

People living in single households especially with children, in large households and those who are poorly educated or foreigners were the most vulnerable to material deprivation (see Figure 18).

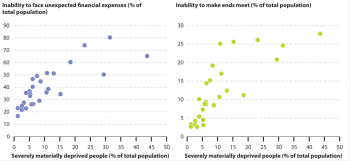

Inability to face unexpected financial expenses or to make ends meet

Material deprivation can threaten a person’s existence or make them fear that their existence is threatened. They may feel unable to face unexpected financial expenses or to make ends meet (the ability to pay for their usual expenses). In 2011 about 38 % of the EU population reported that their household was not able to face unexpected expenses. About 10 % declared they had great difficulties making ends meet. As shown in Figure 19, material deprivation is often associated with these concerns. In countries with fewer severely materially deprived people, more could afford unexpected or usual expenses. Countries with more materially deprived people were more likely to exhibit higher numbers of people unable to face unexpected expenses or make ends meet.

Lack of access to labour lowers income security

In 2011, 10.2 % (or 38.5 million) of the EU population aged 0 to 59 were living in households with very low work intensity. This means the working age members of the household worked less than 20 % of their potential during the previous year. Across Europe, this figure ranged from less than 6 % in Cyprus and Luxembourg to more than 13 % in Belgium and Ireland (see Figure 20). Lack of access to labour increased between 2005 and 2006 before declining between 2006 and 2008. It then remained stable for one year but started to increase again gradually in parallel with the rising unemployment levels as a result of the crisis. Between 2008 and 2011 Latvia, Lithuania, Spain and Estonia reported the highest increases in the amount of households with very low work intensity (147 %, 141 %, 97 % and 87 % respectively). The biggest improvements were observed in Romania (– 18 %) and Poland (– 13 %).

Some countries reported that the share of people living in households with very low work intensity increased by a similar amount to the decrease in the employment rate in the same period. In some cases such as Greece and Spain the increase was even stronger. This trend indicates that a deterioration in employment rates has the biggest effect on the most vulnerable households (20) (see ‘Employment’ chapter, p. 27).

In many countries the rate of lack of access to labour does not seem to correspond to the extent of the other forms of poverty or social exclusion: material deprivation and monetary poverty. Ireland, for example, in 2011 had a high proportion of households with very low work intensity (24.1 %) despite its risk of monetary poverty (15.2 %) being below the EU average. In contrast, Bulgaria had the highest proportion of its population living at risk of monetary poverty, although its share of households with very low work intensity was only slightly above the EU average.

Work intensity lowest for single parents and single households

In many cases, low work intensity means low income. In 2011, one out of every three people in the lowest income quintile in the EU was living in a household with very low work intensity. This figure increases to one in two for single people and almost one in two for single parent households in this lowest income quintile.

In 2011 single parents were 2.5 times more likely to live in a household with very low work intensity than the average. However, unlike the other forms of poverty, large households with children were less likely to experience very low work intensity than single-person households. Single people were twice as likely to live in a household facing problems accessing labour than the average. The most vulnerable groups for labour exclusion were therefore single parents and single people. A quarter of single-parent households and 20 % of single households were affected by very low work intensity in 2011.

Education is one of the keys to lifting people out of poverty. People with a low level of education find it hardest to gain work. In 2011 nearly 20 % of this group were living in a household with very low work intensity. This represents an increase of 3.6 percentage points since 2008. Migrants, especially women, also face greater difficulty finding work. In 2011, 17.2% of women originating from a country outside the EU lived in households with low work intensity. With regard to gender and age groups, women aged 25 to 59 are the most vulnerable to low work intensity.

Lack of work drives monetary poverty and material deprivation

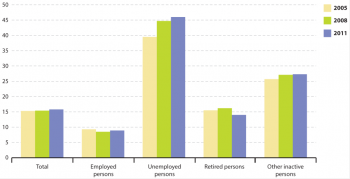

As depicted in the ‘greener, more inclusive - employment Employment’ chapter , unemployment and economic inactivity are major drivers of monetary poverty and material deprivation. Figure 21 illustrates the variations of the risk of monetary poverty by economic activity and the shifts between 2005, 2008 and 2011.

Being unemployed poses the highest risk of monetary poverty. In 2011 almost every second unemployed person was at risk of poverty after social transfers. Also, 27.3 % of other economically inactive people were at risk of poverty. With the exception of retired people, these risks have risen since 2008. For example, the at-risk-of-poverty rate of unemployed people increased from 44.7 % in 2008 to 46 % in 2011.

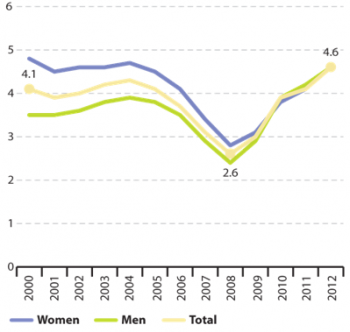

Long-term unemployed people have more difficulty finding work than those unemployed for shorter periods. As a result they face a particularly high risk of poverty and social exclusion. Figure 22 shows that in 2012 4.6 % of the economically active population had been unemployed for longer than a year. This is the highest level over the past decade. It also represents a considerable worsening of the situation compared with five years before, when the long-term unemployment rate had been at a low of 2.6 %. In addition, differences between men and women have disappeared. This was particularly the case during the recent rise in long-term unemployment brought on by the economic crisis.

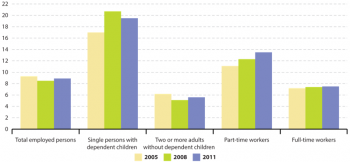

People in work can also be affected by poverty

Poverty and social exclusion do not only affect those who are economically inactive or unemployed. Some groups among those in work also face higher risks of being poor. The developments of income-related aspects of poverty and lack of access to labour are also interrelated with in-work poverty (see Figure 23).

Multi-person adult households without dependent children are much less at risk of in-work poverty than households with dependent children and single-person households. Those most at risk, however, are single parents. One out of five was affected in 2011. Part-time employment can also lead to this form of poverty.

In general men were more affected by in-work poverty than women (9.5 % compared with 8.3 % in 2011). The situation was the opposite for young workers aged 18 to 24 years. In this case women were more affected (12.2 % compared with 10.4 %). Of all age groups, young workers showed the highest in-work at-risk-of-poverty rates.

Conclusions and outlook towards 2020

The European Commission has a goal to reduce the number of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion by 20 million by 2020 compared with 2008. Nevertheless, almost every fourth person in the EU was still at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2011.

Monetary poverty is the most widespread form of poverty. The number of people at risk of poverty after social transfers in 2011 was 83.5 million or 16.9 % of the total EU-27 population. Next was material deprivation, covering 43.4 million people or 8.8 % of all EU citizens. The third dimension is low work intensity, with 38.5 million people experiencing it in 2011. This equals 10.2 % of the total population aged 0 to 59.

The year 2009 marks a turning point in the development of all three dimensions of poverty. While monetary poverty had been stable until 2009 and started to increase afterwards, the other two dimensions decreased considerably until 2009 and started to increase from then on.

Furthermore, the analysis shows that across all three dimensions of poverty, the same groups appear the most vulnerable: young people, single parents, households with many children, people with low educational attainment, and migrants.

Almost 30 % of young people aged 18 to 24 and 27.1 % of children aged less than 18 were at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2011. Moreover, one out of five children and young people aged 18 to 24 were subject to monetary poverty.

Poverty also seemed to be much more pronounced for the less educated and migrants. About 35.0 % of adults with at most lower secondary educational attainment and 32.6 % of adults with a migrant background were in the group of high risk of poverty or social exclusion. Of all groups examined, single parents with one or more dependent children faced the greatest risk of poverty. They were the most affected by low work intensity (25.9 %), monetary poverty (34.5 %), in-work poverty (19.4 %) and material deprivation (18.4 %). Overall, about 50 % of all single parents were at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2011. This was double the average and higher than in any other household type or group analysed.

The development of the risk of poverty and social exclusion indicators also shows a growing gap between high-risk and low-risk groups since 2009. This suggests that the burden of the financial crisis has fallen more heavily on those who already belonged to the weakest groups.

Efforts needed to meet the Europe 2020 target on poverty and social exclusion

As the most widespread form of poverty, monetary poverty is one of the major challenges to achieving the Europe 2020 target. The proportion of people at risk of monetary poverty is closely linked to income inequality. This is not reduced by simply raising the average income. Therefore an area where action needs to be taken is social protection and improving the efficiency and effectiveness of income support [16].

To make progress towards the Europe 2020 poverty goal it will be particularly important to focus on groups of society that are at high risk of poverty and social inclusion.

Actions to be taken for this purpose have been outlined in the EU flagship initiatives ‘Youth on the move’, ‘An Agenda for new skills and jobs’ and ‘European Platform against poverty’. Given poverty’s multifaceted nature, integrated strategies are needed to effectively support those at risk of poverty, so they can fully participate in the economy. Challenges faced by the Member States can be analysed with reference to three aspects: adequate income support, inclusive labour markets and access to quality services. These are the pillars of a comprehensive strategy to fight against poverty that the European Commission has identified in its recommendation on active inclusion. Among the main tools for addressing income poverty are improving the effectiveness and efficiency of tax and benefit systems. The promotion of labour market inclusion requires not only removing entry barriers for particular marginalised groups (such as people with low skills, care responsibility, disability, migrant background or subject to other discriminatory factors), but also tackling in-work poverty. Access to quality services refers to services essential for healthy development and social inclusion such as childcare, housing, healthcare and education [17].

Data sources and availability

Measuring poverty in absolute and relative terms

Absolute poverty refers to the deprivation of basic human necessities for survival, such as food, clean water, clothing, shelter, health care and education. The poverty line is considered the same for different countries, cultures and technological levels. For example, absolute poverty can be measured as the number of people eating less food than is needed to sustain the human body[18].

Relative poverty occurs when someone’s standard of living and income are much worse than the general standard in the country or region where they live. They may struggle to live a normal life and to participate in ordinary economic, social and cultural activities. Relative poverty depends on the standard of living enjoyed by the majority in the country. For example, it can be measured by the number of people living below a country-specific poverty threshold. Relative poverty measures are often closely linked to inequality [19].

What is social exclusion?

Social exclusion can be defined as ‘a process whereby certain individuals are pushed to the edge of society and prevented from participating fully by virtue of their poverty, or lack of basic competencies and life-long learning opportunities, or as a result of discrimination. This distances them from job, income and education and training opportunities, as well as social and community networks and activities. They have little access to power and decision-making bodies and thus often feel powerless and unable to take control over the decisions affecting their day-to-day lives’ [20].

Education and employment policies targeting young people

The Europe 2020 strategy puts forward a flagship initiative focusing on young people. ‘Youth on the move’ aims to enhance the performance of education systems and help young people find work. This is to be done by raising the quality of all levels of EU education and training, promoting student and trainee mobility and improving the employment situation of young people [21].

The flagship initiative ‘A European platform against poverty’ focusing on migrants’ integration

The flagship initiative ‘A European platform against poverty’ incorporates policies focusing on integrating the most vulnerable groups of the population. It aims to provide innovative education, training and employment opportunities for deprived communities, fight discrimination and develop a new agenda to help migrants integrate and take full advantage of their potential. To underpin this, the initiative asks Member States to define and implement measures, addressing the specific circumstances of groups at particular risk, such as minorities and migrants [22].

The headline indicator ‘People at risk of poverty or social exclusion’ combines three dimensions of poverty

Measuring poverty and social exclusion requires a multidimensional approach. Household income is a key determinant of standard of living, but other aspects preventing full participation in society such as access to labour markets and material deprivation also need to be considered. Therefore, the European Commission adopted a broad ‘At-risk-of-poverty or social exclusion rate’ indicator to serve the purposes of the Europe 2020 strategy. This indicator is an aggregate of three sub-indicators: (1) monetary poverty, (2) material deprivation and (3) low work intensity.

1. Monetary poverty is measured by the indicator ‘People at risk of poverty after social transfers’. The indicator measures the share of persons with an equivalised disposable income below the risk-of-poverty threshold. This is set at 60% of the national median equivalised disposable income after social transfers. Social transfers are benefits provided by national or local governments, including benefits relating to education, housing, pensions or unemployment.

2. Material deprivation covers issues relating to economic strain, durables and housing and environment of the dwellings. Severely materially deprived persons have living conditions greatly constrained by a lack of resources and cannot afford at least four of the following: to pay their rent or utility bills, to keep their home warm, to pay unexpected expenses, to eat meat, fish or other protein-rich nutrition every second day, a week holiday away from home, to own a car, a colour TV or a telephone.

3. Very low work intensity describes the number of people aged 0 to 59 living in households where the adults worked less than 20 % of their work potential during the past year.

Because there are intersections between these three dimensions, they cannot simply be added together to give the total number of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion. Some people are affected by two, or even all three, types of poverty. Taking the sum of each type would lead to cases being double-counted. This will become clearer when looking at the current numbers of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion (see Figure 10).

Context

Poverty and social exclusion - why do they matter?

Poverty and social exclusion harm individual lives and limit the opportunities for people to achieve their full potential by affecting their health and well-being and lowering educational outcomes. This, in turn, reduces opportunities to lead a successful life and further increases the risk of poverty. Without effective educational, health, social and employment systems, the risk of poverty is passed from one generation to the next. This causes poverty to persist and hence more inequality, which can lead to long-term loss of economic productivity from whole groups of society [23] and hamper inclusive and sustainable economic growth.

To prevent this downward spiral, the European Commission has made ‘inclusive growth’ one of the three priorities of the Europe 2020 strategy. It has set a target to lift at least 20 million people out of the risk of poverty and social exclusion by 2020. To underpin this objective, the European Commission has launched two flagship initiatives under the ‘inclusive growth’ priority: the ‘Agenda for new skills and jobs’ [24] and the ‘European platform against poverty and social exclusion’ [25].

The strategy’s poverty target is monitored with the headline indicator ‘People at risk of poverty or social exclusion’. This indicator is based on a multidimensional concept, incorporating three sub-indicators on monetary poverty (‘People at risk of poverty after social transfers’), material deprivation (‘Severely materially deprived people’) and low work intensity (‘People living in households with very low work intensity’). Due to the structure of the survey on which most of the key social data is based (EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC)), a large part of the main social indicators available in 2010 (when the Europe 2020 strategy was adopted) referred to 2008 as the most recent year of data available [26]. This is the reason for using 2008 as a baseline year for monitoring progress.

Additional contextual indicators are used to present a broader picture and show the drivers behind the changes in the headline indicator. They break down the top-level indicator by sex, age, educational attainment level, household type, country of birth and labour status. They also help identify the groups most at risk and reveal how their vulnerability has changed over time. Some indicators refer to factors that put people at risk of poverty and social exclusion or support their emergence from this status. These include social protection expenditures and long-term unemployment, which are linked to employment indicators (see the ‘greener, more inclusive - employment Employment’ chapter).

Employment and education help people escape poverty. Thus, the EU’s poverty target is interrelated with the other Europe 2020 targets. Achievement of the target to reduce the number of people at risk of poverty and social exclusion therefore also depends on successful implementation of the priorities and actions addressing the other targets.

Further Eurostat information

Publications

Main tables

Dedicated section

Methodology / Metadata

- Towards robust quality management for European Statistics - Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council COM(2011) 211 final

Other information

- Regulation 223/2009 of 11 March 2009 on European statistics

External links

See also

Notes

- ↑ European Council conclusions 17 June 2010, EUCO 13/10, Brussels, 2010.

- ↑ European Commission, Social Europe — Current challenges and the way forward. Annual Report of the Social Protection Committee (2012), Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2013, (p. 8).

- ↑ See http://ec.europa.eu/europe2020/pdf/targets_en.pdf.

- ↑ European Council conclusions 17 June 2010, EUCO 13/10, Brussels, 2010.

- ↑ European Commission, Social Europe — Current challenges and the way forward. Annual Report of the Social Protection Committee (2012), Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2013, (p. 12).

- ↑ European Commission, Social Europe — Current challenges and the way forward. Annual Report of the Social Protection Committee (2012), Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2013, (p. 18).

- ↑ European Commission, Social Europe — Current challenges and the way forward. Annual Report of the Social Protection Committee (2012), Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2013, (p. 8).

- ↑ European Commission, Europe 2020 — A Strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, COM(2010) 2020 final, Brussels, 2010.

- ↑ European Commission, Social Europe — Current challenges and the way forward. Annual Report of the Social Protection Committee (2012), Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2013, (p. 17).

- ↑ European Commission, The social dimension of the Europe 2020 strategy. A report of the social protection committee, Luxembourg, 2011, (p. 21).

- ↑ European Commission, The European Platform against Poverty and Social Exclusion: A European framework for social and territorial cohesion, COM (2010) 758 final, Brussels, 2010, (p. 5).

- ↑ European Commission, The social dimension of the Europe 2020 strategy. A report of the social protection committee, Luxembourg, 2011, (p. 21).

- ↑ European Commission, Europe 2020 Targets: Poverty and social exclusion. Active inclusion strategies, (p. 4) (accessed 23 July 2013).

- ↑ The GINI coefficient measures the extent to which the distribution of income within a country deviates from a perfectly equal distribution. A coefficient of 0 expresses perfect equality where everyone has the same income, while a coefficient of 100 expresses full inequality where only one person has all the income.

- ↑ European Commission, Social Europe — Current challenges and the way forward. Annual Report of the Social Protection Committee (2012), Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2013, (p. 27).

- ↑ European Commission, Improving the efficiency of social protection, Lisbon, 2011, (p. 8).

- ↑ European Commission, Europe 2020 Targets: Poverty and social exclusion. Active inclusion strategies, (p. 5ff) (accessed 23 July 2013).

- ↑ European Anti-Poverty Network, Poverty and inequality in the EU, EAPN Explainer, 2009, (p. 5ff).

- ↑ European Anti-Poverty Network, Poverty and inequality in the EU, EAPN Explainer, 2009, (p. 5ff).

- ↑ European Commission (Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion), Employment and Social Developments in Europe 2011, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2012 (p. 144).

- ↑ European Commission, Youth on the Move: An initiative to unleash the potential of young people to achieve smart, sustainable and inclusive growth in the European Union, Brussels, 2010.

- ↑ European Commission, The European Platform against Poverty and Social Exclusion: A European framework for social and territorial cohesion, COM(2010) 758 final, Brussels, 2010.

- ↑ European Commission, Social trends and dynamics of poverty, ESDE conference, Brussels, 2013.

- ↑ European Commission, An Agenda for new skills and jobs: A European contribution towards full employment, COM(2010) 682 final, Strasbourg, 2010.

- ↑ European Commission, The European Platform against Poverty and Social Exclusion: A European framework for social and territorial cohesion, COM(2010) 758 final, Brussels, 2010.

- ↑ European Commission, Social Europe — Current challenges and the way forward. Annual Report of the Social Protection Committee (2012), Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2013, (p. 12).

[[Category:<Subtheme category name(s)>|Europe 2020 indicators - poverty and social exclusion]] [[Category:<Statistical article>|Europe 2020 indicators - poverty and social exclusion]]