Archive:Key figures on the changes in the labour market

Data extracted in March 2022

Planned article update: July 2022

Highlights

The COVID-19 pandemic has slowed economic activity and, as a result, the labour market. It clearly had a negative impact on employment but also pushed out people of unemployment by affecting their availability or their job search.

This article aims to present the key consequences of the COVID-19 crisis on the labour market and its recovery for the age category 15-74, focusing on employment, the total unmet demand for employment (also known as the labour market slack) and the share of people who are neither employed, available to work, nor looking for job. All three categories together refer to the entire population as a whole.

An overview of the changes in the labour market is provided on a long-term basis but also for some reference quarters, investigating the extent and effects of the COVID crisis as well as the signs of recovery, at EU level and in the respective Member States, EFTA countries (Iceland, Norway, Switzerland) and candidate countries (Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia and Turkey). It makes use of quarterly data from the European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS).

This article is part of the online publication Labour market in the light of the COVID 19 pandemic - quarterly statistics.

Full article

Rationale to supplement unemployment

The evolution of the population by labour category can be analysed using the European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS) data available from the first quarter of 2009 to the third quarter of 2021. This overview on the labour market shows that in the period before the COVID-19 pandemic, drops in employment were mainly compensated by an increase in unemployment as defined by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) criteria. Unemployment might have been considered as a mirror indicator of employment. However, it can be clearly seen that the COVID-19 challenged this statement.

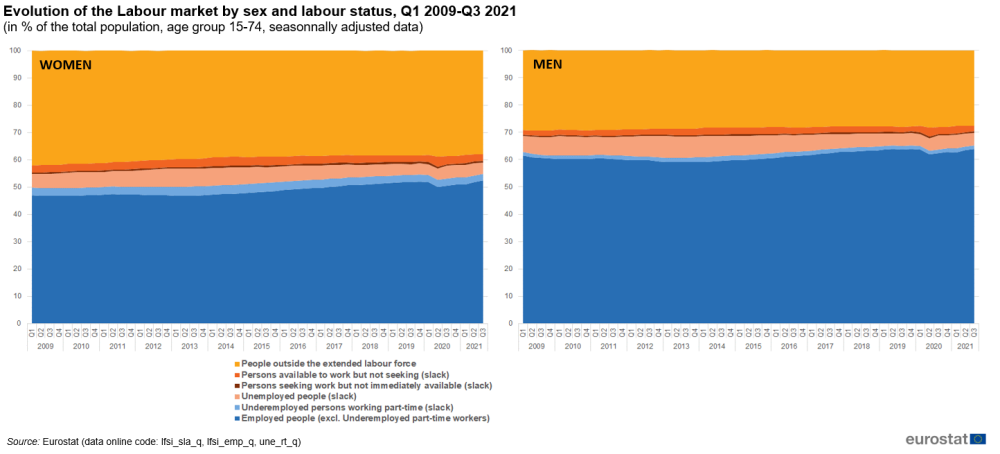

A closer look at the various categories of the labour market shows that people available to work but not seeking work (shown in red in Figure 1) increased by 1.4 percentage points (p.p.) for women and by 1.5 p.p. for men from Q4 2019 to Q2 2020. Then, this category decreased significantly from Q2 2020 to Q3 2020 both for women (-0.8 p.p.) and men (-0.9 p.p.). Finally, this category almost reached the pre-pandemic levels in Q3 2021, being only 0.1 p.p. higher for women and 0.2 p.p. for men compared with Q4 2019.

The labour market slack, which is defined as the unmet needs for employment, gives a better indication of the impact of the pandemic than the single unemployment indicator. The labour market slack encompasses, in addition to unemployed people, the underemployed part-time workers and the potential additional labour force that refers to: (1) people who are available to work but are not looking for a job and (2) people who are looking for a job but are not immediately available. For further explanations on the concept of the labour market slack and a detailed analysis by sex, see the Labour market slack in detail article. While the labour force only covers employed and unemployed individuals, the extended labour force also encompasses the previously referred to potential additional labour force.

In addition, specifically in the context of the pandemic, it is also worth considering the remaining category including people outside the extended labour force to provide a complete overview, as this category also expanded during the crisis. Indeed, people might have been not available and not looking for a job, then excluded from the labour force because of, among other factors, lockdowns, closure of businesses and schools. Changes are further described in the next section.

(in % of the total population, age group 15-74, seasonally adjusted data)

Source: Eurostat (lfsi_sup_q), (lfsi_sla_q), and (lfsi_emp_q)

Impact and recovery

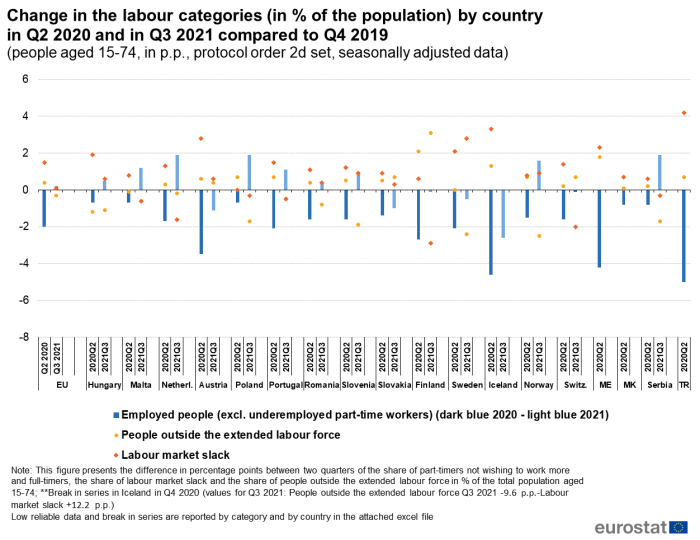

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the labour categories (i.e. employed people, labour market slack and people outside the extended labour force) is measured for each country by the difference in percentage points between Q4 2019 (the last pre-pandemic quarter) and Q2 2020 (the quarter in which the employment was the most impacted by the pandemic) for each labour category. In the same way, an insight into the recovery is given by the difference in percentage points between Q4 2019 and Q3 2021. Results are presented at EU level and for each country.

At EU level, the share of employed people aged 15-74 (excluding underemployed part-time workers) was 57.9 % in Q4 2019, and decreased to 55.9 % in Q2 2020 (-2.0 p.p.). The drop in employment has been compensated by an increase in the labour market slack of 1.5 p.p. (from 8.9 % to 10.4 %) and an increase in people outside the extended labour force (+0.4), who are those people who are not employed, neither available to work nor seeking work. The sum of all changes is nil, as all categories have the same denominator, i.e. the total population, the difference being only due to rounding.

In Q3 2021, the share of employed people reached 58.1 %. This increase of 0.2 p.p. compared to Q4 2019 was accompanied by a slight increase in the labour market slack, from 8.9 % to 9.0 % (+0.1 p.p.) and they were outweighed by a decrease in the category of people outside the extended labour force, which went down from 33.2 % in Q4 2019 to 32.9 % in Q3 2021 (-0.3 p.p.).

(people aged 15-74, in p.p., protocol order 1st set, seasonally adjusted data)

Source: Eurostat (lfsi_sup_q), (lfsi_sla_q), and (lfsi_emp_q)

(people aged 15-74, in p.p., protocol order 2d set, seasonally adjusted data)

Source: Eurostat (lfsi_sup_q), (lfsi_sla_q), and (lfsi_emp_q)

Following this approach, figures 2A and 2B show the development of each category, i.e. employed people whose need for work is met, labour market slack and people outside the extended labour force, expressed in % of the total population, by country.

Greece and Ireland recorded the largest declines in Q2 2020

All countries, without exception, recorded a decline in the share of employed people aged 15-74 between Q4 2019 and Q2 2020. Greece was strongly impacted by the pandemic with a drop of 6.1 p.p., the largest decrease recorded in the share of employed people aged 15-74 between Q4 2019 and Q2 2020 among EU Member States. Ireland followed with a decrease of 5.7 p.p. in its employment rate; this decrease was accompanied by a significant increase in the labour market slack (+3.7 p.p.) and for people outside the extended labour force (+2.0 p.p.).

Estonia, Spain, Italy and Austria recorded decreases of about 3.5 p.p. between Q4 2019 to Q2 2020. In these countries, the drop in employment was offset by a sharp increase in the labour market slack (Austria +2.8 p.p., Spain +2.3 p.p., Estonia +2.1 p.p. and Italy +1.9 p.p.).

By contrast, the decrease in the share of employed people was the lowest in Czechia, Belgium, Malta, Poland, Hungary and Latvia, all recording decreases below 1 p.p. This does not mean that there was no change in the other categories. In Hungary, for example, employment decreased by 0.7 p.p. while the labour market slack increased by 1.9 p.p. and people outside the extended labour force decreased by 1.2 p.p.. Latvia experienced the same, with a decrease in employment (-0.9 p.p.) and for people outside the extended labour force (-0.6 p.p.) which was accompanied by an increase in the labour market slack (+1.5 p.p.).

Employment of people aged 15-74 reached its pre-pandemic level in half the Member States

Fourteen EU Member States recorded a share of employed people aged 15-74 higher in Q3 2021 than in Q4 2019 (last pre-pandemic quarter). For those 14 countries, the progression was at most 2 p.p. above the Q4 2019 share. The largest progressions can be found in Poland and the Netherlands (both by +1.9 p.p.), followed by Luxembourg (+1.7 p.p.), Ireland and Greece (both with +1.6 p.p.), Cyprus (+1.4 p.p.), Malta (+1.2 p.p.) and Portugal (+1.1 p.p.).

By contrast, in Estonia, Latvia, Bulgaria, Italy and Austria, the share of employed people aged 15-74 was still below the pre-pandemic level in Q3 2021, and the gap was larger than 1 p.p. :

- In Estonia, the share of employed people in Q3 2021 was 2.7 p.p. less than the share for Q4 2019, while people outside the extended labour force was 1.7 p.p. higher and the labour market slack was 1.0 p.p. higher than in Q4 2019.

- In Latvia, the decrease in employment (-2.5 p.p.) between Q4 2019 and Q3 2021 was offset by a similar increase in the remaining categories (around 1.2 p.p. each).

- Bulgaria and Italy had a similar pattern as the decrease in the share of employed people (-1.2 and -1.1 p.p. respectively) together with a decrease in the labour market slack (-0.3 p.p. and -0.1 p.p.) were counterbalanced by a significant increase in people outside the extended labour force (+1.5 p.p. and +1.1 p.p.).

- Finally, in Austria, where employment dropped by 1.1 p.p., the labour market slack and people outside the extended labour force increased to a similar extent (+0.6 p.p. and +0.4 p.p.).

Young employed people aged 15-29: still the most affected

As further explained in the article on employment, young people aged 15-24 have been strongly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Young people, according to the United Nations definition, indeed refer for statistical purpose to the age group 15-24.

However, the age category 15-29 also deserves attention as it is considered as the reference in the Year of Youth context. For this reason, the current section presents the change in the employment rate specifically for young people aged 15-29.

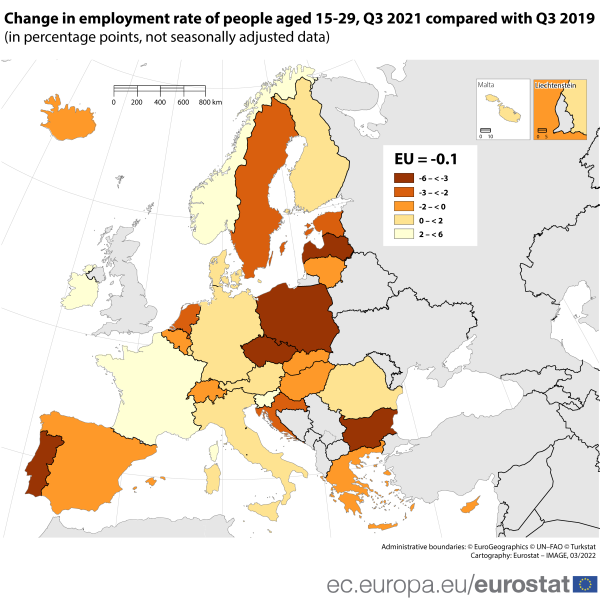

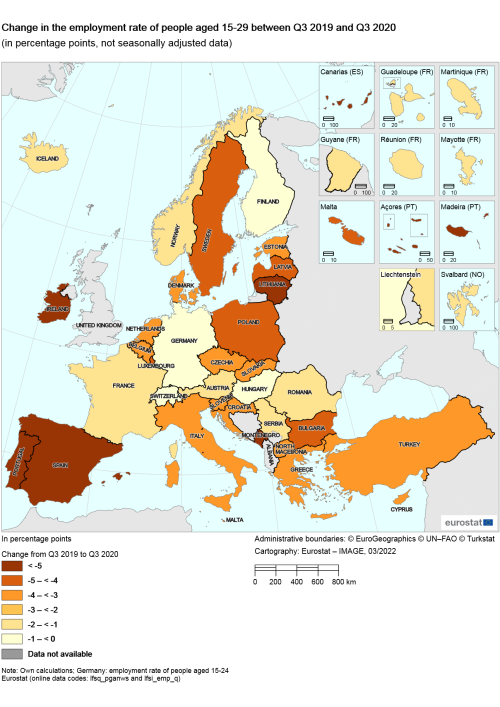

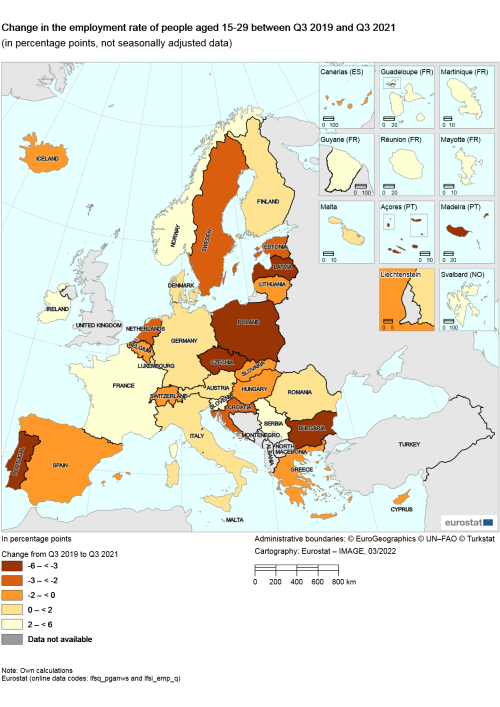

Developments linked to the impact of the COVID-19 crisis and to the recovery for young people 15-29 are presented in two maps, that compare Q3 2020 and Q3 2021 with Q3 2019 (pre-pandemic level). The same quarter (Q3) is taken for the three years as no seasonally adjusted data is available for the specific age group 15-29.

At EU level, the share of employed people aged 15-29 decreased by 2.8 p.p. between Q3 2019 and Q3 2020. However, even if the employment rate of young people dropped in all Member States, countries have not been impacted in the same way. Looking at Figure 3A, the largest drops in the employment rates of people aged 15-29 were recorded in Lithuania, Portugal, Ireland and Spain, all reporting a decrease larger than 5 p.p. In Sweden, Poland, Malta, Latvia, Bulgaria and Luxembourg, the employment rate of people aged 15-29 decreased by 4 or 5 p.p. By contrast, Hungary, Finland, France, Austria and Romania recorded the smallest decreases, all less than 2 p.p.

In terms of recovery, the EU employment rate of young people in Q3 2021 was still 0.1 p.p. below the Q3 2019 level. Ireland, France and Slovenia showed the largest progress in the share of employed people aged 15-29 compared to the pre-pandemic situation: in these three Member States, the employment rate for young people in Q3 2021 was more than 2 p.p. higher than the one in Q3 2019. In Romania, Luxembourg and Finland, the share of employed people aged 15-29 also exceeded the Q3 2019 level but to a lesser extent, the increases being between 1 p.p. and 2 p.p.

However, the labour market of 16 EU Member States did not fully recover from the pandemic for young people, as their employment rate in Q3 2021 in these countries remained below the rate recorded in Q3 2019. This was the case in particular for Portugal, Bulgaria, Latvia, Czechia and Poland, where the share of young employed people was at least 3 p.p. below the pre-pandemic level.

(in percentage points, not seasonally adjusted data)

Source: Eurostat (lfsq_pganws) and (lfsi_emp_q)

(in percentage points, not seasonally adjusted data)

Source: Eurostat (lfsq_pganws) and (lfsi_emp_q)

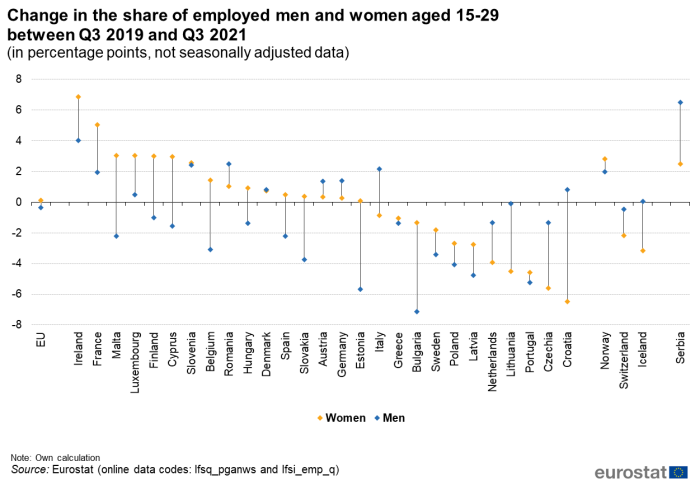

Another relevant finding is that, at EU level, the employment rate of women aged 15-29 had in Q3 2021 reached its pre-pandemic level (an increase of 0.1 p.p. is even recorded between Q3 2019 and Q3 2021) while the share of employed young men lagged behind the pre-pandemic level (decrease of 0.3 p.p. between Q3 2019 and Q3 2021). This pattern is reflected in two thirds of the countries; 18 EU Member States recorded a larger increase (vs a smaller decrease) for women than for men.

In one country, i.e. Denmark, no differences were observed between the development of the employment rate for young men and women. Finally, in 8 countries, i.e. Romania, Austria, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Lithuania, Czechia and Croatia, the share of employed young men in Q3 2021 increased more (or decreased less) than for women. The largest differences between men and women (differences in the developments larger than 5 p.p.) were reported by Croatia, Bulgaria, Estonia and Malta (with better evolution for women except in Croatia).

(in percentage points, not seasonally adjusted data)

Source: Eurostat (lfsq_pganws) and (lfsi_emp_q)

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

All figures in this article are based on quarterly results from the European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS). Some data are seasonally adjusted.

Source: The European Union labour force survey (EU-LFS) is the largest European household sample survey providing quarterly and annual results on labour participation of people aged 15 and over as well as on persons outside the labour force. It covers residents in private households. Conscripts in military or community service are not included in the results. The EU-LFS is based on the same target populations and uses the same definitions in all countries, which means that the results are comparable between countries.

European aggregates: EU refers to the sum of EU-27 Member States.

Country note: (1) In Germany, from the first quarter of 2020 onwards, the Labour Force Survey is part of a new system of integrated household surveys. Unfortunately, technical issues and the COVID-19 crisis has had a large impact on data collection processes, resulting in low response rates and a biased sample. For more information, see here. (2) In the Netherlands, the 2021 quarterly LFS data remains collected using a rolling reference week instead of a fixed reference week, i.e. interviewed persons are asked about the situation of the week before the interview rather than a pre-selected week.

Definitions: The concepts and definitions used in the Labour Force Survey follow the guidelines of the International Labour Organisation.

Time series: Regulation (EU) 2019/1700 came into force on 1 January 2021 and induced a break in the LFS time series for several EU Member States. In order to monitor the evolution of employment and unemployment despite of the break in the time series, Member States assessed the impact of the break in their country and computed impact factors or break corrected data for a set of indicators. Break corrected data are published for the LFS main indicators. For the employment rate of young people aged 15-29, a break correction similar to the one computed for the age group 15-24 has been applied.

More information on the LFS can be found via the online publication EU Labour Force Survey, which includes eight articles on the technical and methodological aspects of the survey. The EU-LFS methodology in force from the 2021 data collection onwards is described in methodology from 2021 onwards. Detailed information on coding lists, explanatory notes and classifications used over time can be found under documentation.

Seasonally adjustment models: The methodological choices of Eurostat in terms of seasonal adjustment are summarised in the methodological paper: "Guidance on time series treatment in the context of the COVID-19 crisis". These choices assure the quality of the results and the optimal equilibrium between the risk of high revisions and the need for meaningful figures, as little as possible affected by random variability due to the COVID shock.

Context

The COVID-19 pandemic hit Europe in January and February 2020, with the first cases confirmed in Spain, France and Italy. COVID-19 infections have been diagnosed since then in all European Union (EU) Member States. To fight the pandemic, EU Member States took a wide variety of measures. From the second week of March 2020, most countries closed retail shops, with the exception of supermarkets, pharmacies and banks. Bars, restaurants and hotels were also closed. In Italy and Spain, non-essential production was stopped and several countries imposed regional or even national lock-down measures which further stifled economic activities in many areas. In addition, schools were closed, public events were cancelled and private gatherings (with numbers of persons varying from 2 to over 50) banned in most EU Member States.

The majority of the preventive measures were initially introduced during mid-March 2020. Consequently, the first quarter of 2020 was the first quarter in which the Labour Market across the EU was affected by COVID-19 measures taken by Member States.

In the following quarters of 2020, as well as 2021, the preventive measures against the pandemic were continuously relaxed and re-enforced in accordance with the number of new cases of the disease. New waves of the pandemic began to appear regularly (e.g. peaks in October-November 2020 and March-April 2021). Furthermore, new strains of the virus with increased transmissibility emerged in late 2020, which additionally alarmed the health authorities. Nonetheless, as massive vaccination campaigns started all around the world in 2021, people began to anticipate improvement of the situation regarding the COVID-19 pandemic.

The quarterly data on employment allows regular reporting of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis on employment. In the publication Labour market in the light of the COVID-19 pandemic, a specific article depicts employment in general and specifically by gender, age and level of educational attainment while another article focuses on employed people and job starters by sector of economic activity and occupation.

However, in this exceptional context of the COVID-19 pandemic, employment and unemployment as defined by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) are not sufficient to describe the developments taking place in the labour market. In the first phase of the crisis, active measures to contain employment losses led to absences from work rather than dismissals, and individuals could not look for work or were not available due to the containment measures, thus not counting as unemployed. Only referring to unemployment might consequently underestimate the entire unmet demand for employment, also called the labour Market slack.

The three indicators supplementing the unemployment rate presented in this article provide an enhanced and richer picture than the traditional labour status framework, which classifies people as employed, unemployed or outside the labour force, i.e. in only three categories. The indicators create ‘halos’ around unemployment. This concept is further analysed in a Statistics in Focus publication titled "New measures of labour market attachment", which also explains the rationale of the indicators and provides additional insight as to how they should be interpreted. The supplementary indicators do not alter or put in question the unemployment statistics standards used by Eurostat. Eurostat publishes unemployment statistics according to the ILO definition, the same definition as used by statistical offices all around the world. Eurostat continues publishing unemployment statistics using the ILO definition and they remain the benchmark and headline indicators.

Direct access to

- All articles on the Labour Market

- Labour market in the light of the COVID 19 pandemic - quarterly statistics

- Employment - quarterly statistics

- Employment in detail - quarterly statistics

- Employment - annual statistics

- Labour market slack – annual statistics on unmet needs for employment

- Labour market statistics at regional level

- New measures of labour market attachment - Statistics in focus 57/2011

- Labour force survey in the EU, EFTA and candidate countries — Main characteristics of national surveys, 2020, 2022 edition

- Quality report of the European Union Labour Force Survey 2019, 2021 edition

- Labour market in the light of the COVID 19 pandemic — online publication

- EU labour force survey — online publication

- European Union Labour force survey - selection of articles (Statistics Explained)

- LFS main indicators (lfsi)

- Unemployment - LFS adjusted series (une)

- Supplementary indicators to unemployment - annual data (lfsi_sup_a)

- Supplementary indicators to unemployment - quarterly data (lfsi_sup_q)

- Unemployment - LFS adjusted series (une)

- LFS series - Detailed annual survey results (lfsa)

- Total unemployment - LFS series (lfsa_unemp)

- Supplementary indicators to unemployment by sex and age (lfsa_sup_age)

- Supplementary indicators to unemployment by sex and educational attainment level (lfsa_sup_edu)

- Supplementary indicators to unemployment by sex and citizenship (lfsa_sup_nat)

- Total unemployment - LFS series (lfsa_unemp)

- LFS series - Detailed quarterly survey results (lfsq)

- Total unemployment - LFS series (lfsq_unemp)

- Supplementary indicators to unemployment by sex and age (lfsq_sup_age)

- Supplementary indicators to unemployment by sex and educational attainment level (lfsq_sup_edu)

- Total unemployment - LFS series (lfsq_unemp)

Methodology

Publications

- EU labour force survey — online publication

- Labour force survey in the EU, EFTA and candidate countries — Main characteristics of national surveys, 2020, 2022 edition

- Quality report of the European Union Labour Force Survey 2019, 2021 edition

- New measures of labour market attachment - Statistics in focus 57/2011

ESMS metadata files and EU-LFS methodology

- Employment and unemployment (Labour Force Survey) (ESMS metadata file — employ_esms)

- LFS series - detailed quarterly survey results (from 1998 onwards) (ESMS metadata file — lfsq_esms)

- LFS series - detailed annual survey results (ESMS metadata file — lfsa_esms)

- LFS ad-hoc modules (ESMS metadata file — lfso_esms)

- LFS main indicators (ESMS metadata file — lfsi_esms)

- LFS regional series (ESMS metadata file — reg_lmk)