Archive:European Neighbourhood Policy - East - statistics on trade in goods with the EU

Data extracted in January 2022.

Planned article update: March 2023.

Highlights

Azerbaijan was the only European Neighbourhood Policy-East country to record an external trade balance surplus in 2020.

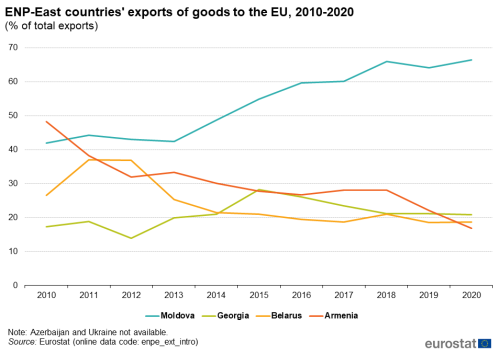

Among the European Neighbourhood Policy-East countries reporting 2020 data, the EU accounted for 66 % of Moldova’s total exports, 21 % of Georgia's, 19 % of Belarus’s and 17 % of Armenia's.

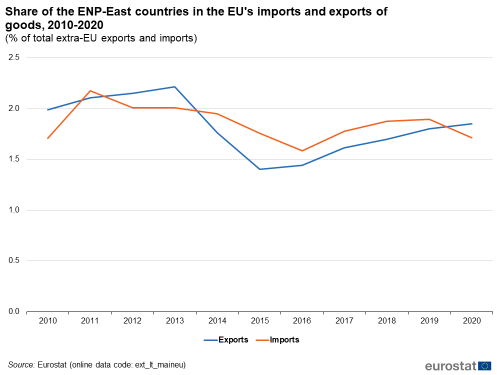

Some 1.8 % of all goods exported from the EU in 2020 were destined for the six European Neighbourhood Policy-East countries, while 1.7 % of EU imports came from these countries.

ENP-East countries exports of goods to the EU, 2010-2020

This article is part of an online publication and presents information relating to recent developments for international trade in goods for the six countries that together form the European Neighbourhood Policy-East (ENP-East) region, namely, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine, in particular concerning their trade relations with the European Union (EU).

Data shown for Georgia exclude the regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia over which Georgia does not exercise control and the data shown for Moldova exclude areas over which the government of the Republic of Moldova does not exercise control. The latest data for Ukraine generally exclude the illegally annexed Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the City of Sevastopol and the territories which are not under control of the Ukrainian government (see specific footnotes for precise coverage).

The article highlights some of the key indicators for tracing developments in the international trade of the ENP-East region over the period 2010-2020, with information on exports, imports and the trade balance. It is followed by an examination of trade between ENP-East countries and the EU from the perspective of the ENP-East countries, using data reported by the ENP-East countries themselves. The subsequent parts of the analysis mirror this approach and look at trade flows to/from ENP-East countries from the perspective of the EU, using Eurostat data. There are differences in the values of trade reported by ENP-East countries and by EU Member States: more information on this phenomenon is provided in the data sources section. It also presents an analysis of international trade between the regions by selected product groups (based on the standard international trade classification (SITC)).

Full article

Exports, imports and the trade balance

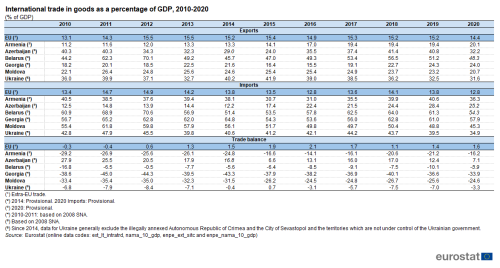

International trade statistics track the value and quantity of goods traded between countries. They are the official source of information on imports, exports and the trade balance, the difference between them. The data in Table 1 show the total exports, imports and the trade balance as a percentage of the GDP of the ENP-East countries and the EU. This allows a focus on the change in the significance of trade flows relative to the size of the economies concerned.

Since the 1970s, global trends saw trade increasing as a proportion of GDP in most countries, although this trend levelled off during the 2010s. Increased trade has been an important element of globalisation, although far from the only one. Countries that are growing fast or are undergoing or recovering from economic difficulties may wish to run trade deficits, in which the value of imports is greater than that of exports. Countries that specialise in providing services to the rest of the world, such as tourism or business services, may also run consistent trade deficits, since services are not included in the statistics of exports and imports of goods. The balance of payments includes data on both trade in goods and in services.

Total trade, the sum of exports and imports (sometimes the average is used), as a percentage of GDP is often used as a measure of a country’s openness to world trade. Smaller countries tend to have higher levels of trade openness than larger ones, since there are fewer opportunities for buying and selling domestically produced goods. The relationship between trade openness and income (measured as GDP per capita) is more complicated, although low income countries generally have low trade openness.

The data in Table 1 show that Armenia’s exports and imports in 2010 were equivalent, respectively, to 11 % and 40 % of GDP. By 2020, Armenia’s exports had risen to 20 % of GDP, with imports down to 36 %. Hence, the trade deficit diminished from 29 % of GDP in 2010 to 16 % in 2020. The trade deficit had been as low as 14 % of GDP in 2016: imports were near their 2015 lows that year and subsequently grew again. The measure of openness to trade was 56 % of GDP in 2020, an increase of 5 percentage points over the period.

Azerbaijan, with its large export-oriented hydrocarbon sector, is the only ENP-East country to show a trade surplus. This started at 28 % of GDP in 2010, then fell to under 7 % in 2015, before rising to 17 % in 2018 and declining to 7 % in 2020. Exports have driven these trends: the high point during the period occurred in 2018, when exports equalled 41 % of GDP. The low point was in 2015, when exports were 24 % of GDP. Imports ranged from 12 % of GDP in 2014 to over 28 % in 2019. Exports plus imports rose by under 5 percentage points over the period, leading to trade openness being measured at 57 % of GDP in 2020.

Belarus has been consistently the most open economy of the ENP-East countries, with aggregate trade (i.e., imports plus exports) at 103 % of GDP in 2020. Over the period 2010-2020, its openness slightly declined by under 3 percentage points. During 2010-2012, both exports and imports grew. This was followed by a sharp decline in 2013. After a further decline, albeit slower, in 2014, a recovery followed, although not to the levels of 2012. Belarus started the period with a trade deficit equal to 17 % of GDP in 2010 before a rapid reduction in 2011 and 2012: exports grew faster than imports. In 2013, the fall in exports was larger than that of imports, so the trade deficit increased, remaining at broadly similar levels since.

(% of GDP)

Source: Eurostat (ext_lt_intratrd), (nama_10_gdp), (enpe_ext_sitc) and (enpe_nama_10_gdp)

Georgia’s exports plus imports in 2020 equalled 82 % of GDP, an increase of 7 percentage points over the 2010 figure. This change was accounted for by an increase in both exports and imports over the period. At the same time, Georgia’s negative trade balance has been fairly consistent: it was in deficit in 2010 at 39 % of GDP and in 2020 at 34 %, which was a low point; its maximum value was 45 % in 2011. Exports as a percentage of GDP have ranged from over 15 % in 2016 to 24 % in 2019. Imports as a percentage of GDP were at their lowest in the period in 2016 at under 54 % and their greatest in 2011 at 65 %.

Moldova’s trade openness was 66 % of GDP in 2020 but was nearly 12 percentage points less than ten years earlier. This was almost entirely due to a fall in imports as a proportion of GDP, which declined in particular from 2014 to 2015. Exports have accounted for a consistent share of GDP: the lowest during the period was 21 % in 2020 and the highest 26 % in 2011. Imports in 2020 were at their lowest proportion of GDP compared with the rest of the period from 2010 at 45 %. The trade balance has improved from a deficit of 33 % of GDP in 2010 to one of under 25 % in 2020; it has been quite stable since 2016.

Ukraine’s aggregate trade was equal to 67 % of GDP in 2020, a fall of 12 percentage points from 2010, due more to the decline in imports as a share of GDP than that of exports. Imports as a share of GDP reached the highest value of 48 % in 2011 and the greatest annual decreases were in 2013, 2019 and 2020 resulting to 35 % of GDP in 2020, the lowest of the period. A jump in exports in 2014 was followed by a decline as a share of GDP from 2016, in particular in 2019. The 2020 figure was almost 32 % of GDP, also the lowest of the period. The country had a balance of trade deficit of 7 % of GDP in 2010, improving to close to zero in 2014 and being positive in 2015 at almost 1 %, before decreasing to a deficit of almost 8 % in 2018, finishing the period at a deficit of 3 % in 2020. In summary, there has been little change in Ukraine’s overall international trade position over the period 2010-2020.

The statistics for the EU are shown for extra-EU trade only, treating the EU as a single trading entity. Its degree of trade openness, at 27 % of its GDP in 2020, is smaller than any of the ENP-East countries, which is due to its much larger economy.

The EU as a trading partner for the ENP-East countries

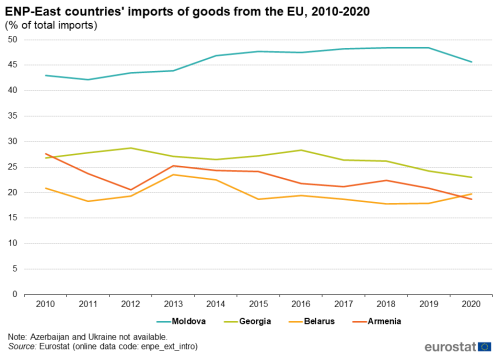

Figures 1 and 2 show the available data for ENP countries’ exports to and imports from the EU as a percentage of their total exports and imports over the period 2010-2020.

For Armenia, there was a clear declining trend in the EU’s share of total exports and imports over 2010-2020. By the end of the period, the EU’s share of Armenia’s exports had dropped by 31 percentage points to 17 % and its share of Armenia’s imports by 9 percentage points to 19 %. The EU’s share of Belarus’s exports fell by 8 percentage over the period to 19 %, while the decline of the share of EU imports was only 1 percentage point to 20 %.

In Georgia, the share of exports to the EU fluctuated over the period 2010-2020, but ended over 3 percentage points higher, at 21 %. In 2020, the share of imports ended 4 percentage points lower than at the outset in 2010, at 23 %. The EU’s share in Moldova’s exports grew from 2010 by over 24 percentage points to 66 % in 2020. The EU’s share in Moldova’s imports, at almost 46 % in 2020, was 3 percentage points higher than in 2010. Both EU export and import shares in Moldova were by far the highest among the reporting ENP-East countries. Moldova’s membership of the Central European Free Trade Agreement presumably contributed to this difference - see the ‘Context’ section below.

(% of total exports)

Source: Eurostat (enpe_ext_intro)

The share of the ENP-East countries' trade with the EU, relative to their GDP, is found by taking the share of exports and imports in GDP (Table 1) and multiplying it by the share of exports and imports to/from the EU in total trade (Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively). For example, Armenia’s total exports in 2020 were equivalent to 20.1 % of GDP. Armenia’s exports to the EU in the same year accounted for 16.9 % of all trade. Multiplying these two percentage yields Armenia’s exports to the EU as share of GDP: in 2020, the result is 3 % of GDP. This calculation provides a measure of the relative importance to the ENP-East countries' economies of their trade with the EU.

As calculated, Armenia’s exports to the EU in 2020 accounted for 3 % of its GDP, a decline of two percentage points from 2010. Its imports in 2020 were equivalent to 7 % of GDP, a decline of over 4 percentage points from 2010. The significance to Belarus’s economy of its exports to the EU declined by around 3 percentage points from 2010 to 2020, to 9 % of GDP. During the same period, its imports from the EU declined by 2 percentage points to 11 % of GDP. Georgia’s exports to the EU accounted for 5 % of GDP in 2020, an increase of 2 percentage points over 2010. At 13 %, the share of its EU imports in GDP was 2 percentage points lower than in 2010. Moldova’s exports to the EU as a percentage of its GDP were around 14 % in 2020, an increase of over 4 percentage points over 2010. The corresponding figure for imports was 21 % in 2020, a decline of 3 percentage points from 2010.

(% of total imports)

Source: Eurostat (enpe_ext_intro)

The ENP-East countries as trading partners for the EU

This section uses statistics compiled by Eurostat from data submitted by EU Member States. This differs from most of this Statistics Explained article, which uses data provided to Eurostat by the ENP-East countries. See the Data Sources section below for more information.

Exports and imports of internationally traded goods to and from the six ENP-East countries are shown as a percentage of the EU’s total external exports and imports in Figure 3. They accounted for a small share of the EU’s trade in 2020, some 1.8 % of all exports leaving the EU and 1.7 % of all imports arriving in the EU from non-member countries.

The relative importance of the EU’s trade in goods with the ENP-East countries has not changed much from 2010 to 2020, a period in which new trade partnerships developed. There is no clear trend during this period.

These statistics contrast with the increased openness to international trade of both the EU and some of the ENP-East countries, as discussed with reference to Table 1.

(% of total extra-EU exports and imports)

Source: Eurostat (ext_lt_maineu)

EU Trade flows with individual ENP-East countries

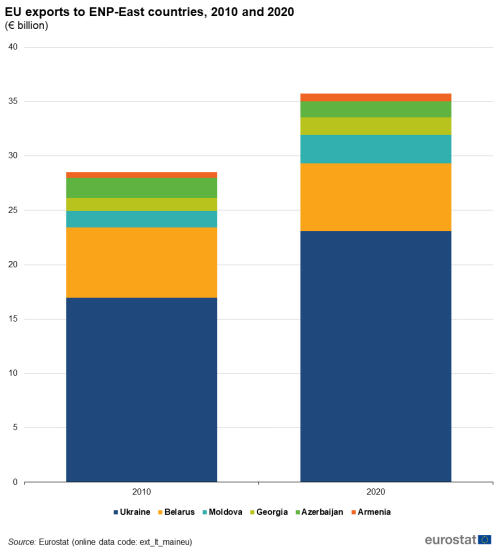

Figures 4 and 5 provide more detailed information as to the destination and origin of trade in goods between the EU and the six ENP-East countries in 2010 and 2020, based on data provided by the EU Member States to Eurostat. The following analyses look at trade valued in Euro.

Ukraine accounted for the largest share of goods exported from the EU to the six ENP-East countries in both 2010 and 2020 (see Figure 4). EU exports of goods to Ukraine were valued at €16.9 billion in 2010 and €23.1 billion in 2020, an annual average growth rate of 3.2 %. Goods from the EU destined for Belarus were valued at €6.5 billion in 2010 and €6.2 billion in 2020, declining on average by 0.4 % per year. The third highest amount of EU exports to the ENP-East countries in 2020 was recorded for Moldova, at €2.6 billion, having been €1.5 billion in 2010, an annual increase of 5.6 %. EU exports to Georgia increased from €1.2 billion in 2010 to €1.6 billion in 2020, an average growth of 3.0 %. Those to Azerbaijan were €1.9 billion in 2010 and €1.5 billion in 2020, an annual decline of 2.1 %. EU exports to Armenia were valued at €540 million in 2010 and €720 million in 2020, an average annual increase of 2.8 %.

(€ billion)

Source: Eurostat (ext_lt_maineu)

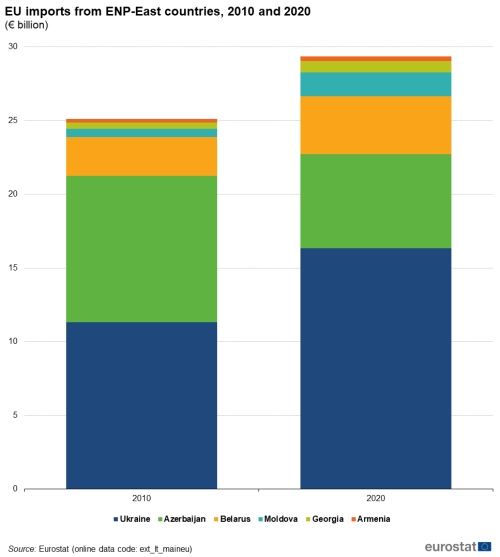

Looking at imports to the EU from ENP-East countries as shown in Figure 5, Ukraine was again the largest trading partner in 2020. Its EU imports were valued at €16.3 billion, up from €11.3 billion in 2010, an average growth rate of 3.7 % a year. Azerbaijan accounted for €6.4 billion of EU imports in 2020, down from €9.9 billion in 2010, an average decline of 4.3 % a year. Belarus was the third largest ENP-East source of imports to the EU in 2020, at €3.9 billion. 2010 imports were €2.6 billion, so average growth was 4.0 % a year. Goods imported to the EU from Moldova were valued at €540 million in 2010 and €1.6 billion in 2020; annual growth was 11.6 %. Imports from Georgia were valued at €420 million in 2010 and €760 million in 2020; growth averaged 6.0 % a year. EU imports from Armenia were €250 million in 2010 and €340 million in 2020, annual growth being 2.9 %.

(€ billion)

Source: Eurostat (ext_lt_maineu)

ENP-East trade flows with individual EU Member States

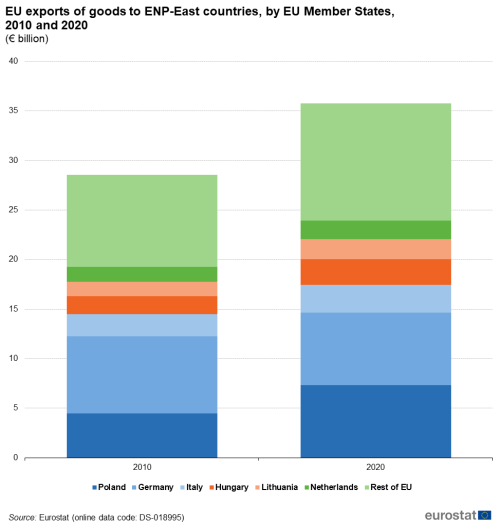

In 2020, as shown in Figure 6, Poland had marginally the highest share of the EU’s goods exported to the ENP-East countries in 2020, at €7.3 billion, having exported €4.5 billion in 2010. These exports increased over the period at an annual average 5.0 %. Germany recorded the second largest exports of goods to the six ENP-East countries from among the EU Member States, just below €7.3 billion; its exports were €7.8 billion in 2010, so they declined at an annual average rate of 0.7 %. Italy exported €2.2 billion worth of goods to the ENP-East countries in 2010 and €2.8 billion in 2020, a growth rate of 2.5 % a year. Hungary exported €1.8 billion in 2010 and €2.6 billion in 2020, so growth was 3.6 % a year. Other significant exporters in 2020 were Lithuania at €2.0 billion and Netherlands at €1.9 billion. Between them, the remaining 21 EU Member States accounted for €11.8 billion worth of goods exports to the ENP-East countries in 2020.

(€ billion)

Source: Eurostat (DS-18995)

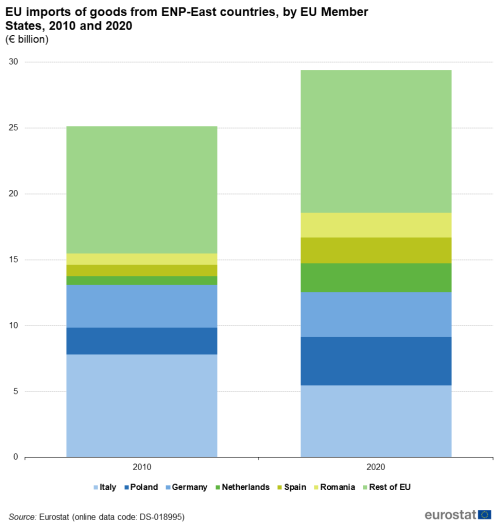

Figure 7 shows that Italy was the largest market among the EU Member States for goods from the ENP-East countries. Italy's imports of goods from the ENP-East countries were valued at €5.5 billion in 2020; its ENP-East imports had been €7.8 billion in 2010, an annual average decline of 3.5 %. Oil and gas imports from Azerbaijan accounted for much of this. Poland was the second largest import market at €3.7 billion in 2020. The growth in its imports from the ENP-East countries from 2010 to 2020 was considerable – they had been €2.0 billion in 2010, a growth rate of 6.1 % a year. Germany was the third largest importer from the ENP-East in 2020, at €3.4 billion; the 2010 figure was €3.3 billion for an annual growth rate of 0.4 %. Other significant EU importers from the ENP-East in 2020 were the Netherlands, €2.2 billion; Spain, €2.0 billion; and Romania, €1.9 billion. Other EU Member States accounted for €10.8 billion of imports from the ENP-East countries in 2020, up from €9.6 billion in 2010.

(€ billion)

Source: (DS-18995)

Main products traded between the ENP-East countries and the EU

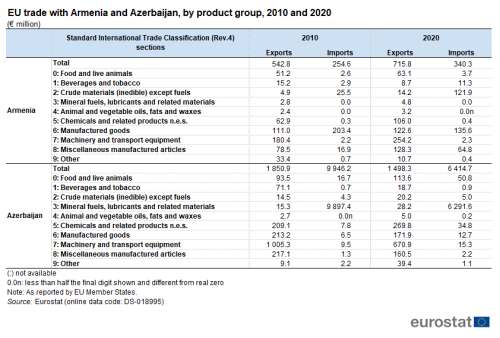

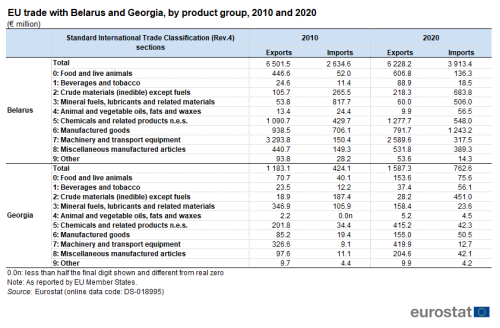

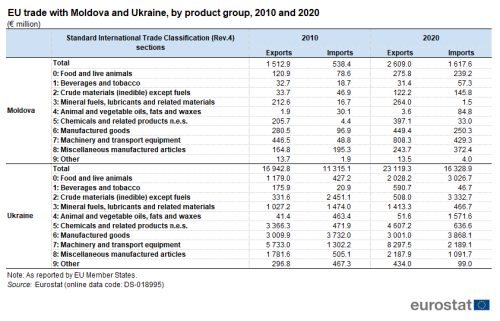

Tables 2a, 2b and 2c provide, for each of the ENP-East countries, an analysis of their trade in goods with the EU by product group, as reported by the EU Member States to Eurostat. The 10 main sections shown follow the standard international trade classification (SITC Rev.4).

The EU’s principal exports to Armenia in 2020 were €254 million worth of machinery and transport equipment (SITC section 7), 36 % of total exports to that country of €716 million. Looking at the trade flow in the opposite direction, the EU imported manufactured goods (SITC section 6) worth €136 million from Armenia, 40 % of a total of €340 million.

Mineral fuels, lubricants and related materials (SITC section 3), at €6 292 million accounted for 98 % of the EU’s imports originating from Azerbaijan in 2020; this section includes coal, oil, natural gas and other petroleum products. Total EU imports from Azerbaijan in 2020 amounted to €6 415 million. EU principal exports to Azerbaijan in 2020 were €671 million of machinery and transport equipment, 45 % of a total of €1 498 million.

(€ million)

Source: Eurostat (DS-18995)

The EU's largest export product group to Belarus in 2020 was machinery and transport equipment, valued at €2 590 million, 42 % of a total of €6 228 million. The EU’s largest imports category from Belarus in 2020 was €1 243 million worth of manufactured goods, 32 % of a total of €3 913 million. In 2010, the EU’s largest product group of imports from Belarus was mineral fuels, lubricants and related materials.

The EU exported €420 million worth of machinery and transport equipment to Georgia in 2020. This was the largest group, accounting for more than 26 % of total EU-Georgia exports of €1 587 million. In 2010, EU exports of mineral fuels, lubricants and related materials were the largest product group. EU imports in 2020 from Georgia of €451 million of crude materials (inedible) except fuels (SITC section 2) were by far the largest product group, at 59 % of a total of €763 million. Growth in EU imports from Georgia of this product group over 2010-2020 has averaged 9.2 % a year.

(€ million)

Source: Eurostat (DS-18995)

The largest EU exports to Moldova in 2020 were €808 million of machinery and transport equipment, 31 % of a total of €2 609 million. The largest EU imports in 2020 were in the same product group: €429 million, 27 % of a total of €1 618 million. In 2010, the largest product group imported to the EU had been miscellaneous manufactured articles (SITC section 8).

In Ukraine, by far the largest EU export product in 2020 was machinery and transport equipment, accounting for €8 297 million, 36 % of a total of €23 119 million. In second place was chemicals and related products, (SITC section 5), valued at €4 607 million, 20 % of the total. Manufactured goods provided the largest value of EU imports in 2020, valued at €3 868 million, 24 % of the total. Crude materials (inedible) except fuels (SITC section 2) were the second largest group in 2020, at €3 333 million, 20 % of the total imports to the EU, which were €16 329.

(€ million)

Source: Eurostat (DS-18995)

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

Traditionally, customs records are the main source of statistical data on international trade. Following the adoption of the Single Market in January 1993, customs formalities between EU Member States were removed, and so a new data collection system, intrastat, was set up for intra-EU trade. In the intrastat system, intra-EU trade data are collected directly from trade operators, which send a monthly declaration to the relevant national statistical administration.

The data for ENP-East countries are supplied by and under the responsibility of the national statistical authorities of each country on a voluntary basis. The data result from an annual data collection cycle that has been established by Eurostat. These statistics are available free-of-charge on Eurostat’s website, together with a range of additional indicators for ENP-East countries covering most socio-economic topics.

Note that although trade flows should ideally mirror each other (in other words be the same from the perspective of the exporter and the importer), there may be considerable differences in the values presented depending upon which party (exporter or importer) is used as the reporting entity. This is the case even when the difference is taken into account between the valuation of exports as free on board (fob) and of imports incorporating cost, insurance and freight (cif). These discrepancies are often referred to as asymmetries and can be seen when bilateral data for two reporting parties are compared. Generally, while international recommendations for reporting trade statistics exist, countries may adopt methodologies that deviate from the recommendations for practical reasons. Consequently, when exports from country A to country B are compared with imports into country B from country A, the figures rarely (if ever) match. More information concerning the causes of asymmetries can be found in the user guide for statistics on the trading of goods.

Tables in this article use the following notation:

| Value in italics | data value is forecast, provisional or estimated and is therefore likely to change; |

| : | not available, confidential or unreliable value; |

| 0.0n | less than half the final digit shown and different from real zero. |

Context

The EU has a common international trade policy, often referred to as the common commercial policy. In other words, the EU acts as a single entity on trade issues, including issues related to the World Trade Organisation (WTO). In these cases, the European Commission negotiates trade agreements and represents the interests of the EU Member States.

The EU seeks to promote the development of free trade as an instrument for stimulating economic growth and enhancing competitiveness. International trade statistics are of prime importance for both public sector (decision makers at international, EU and national levels) and private users (in particular, businesses who wish to analyse export market opportunities) as they provide valuable information on developments regarding the exchange of goods between specific geographical areas. These statistics enable the EU to monitor the development of trade ties with its ENP partners, while they are also used by the European Commission to prepare multilateral and bilateral negotiations for common trade policies.

Moldova, together with the Western Balkan countries, is a member of the Central European Free Trade Agreement (CEFTA). CEFTA seeks to promote trade within the Central European region by eliminating tariffs to regional trade and identifying and reducing non-tariff barriers to trade.

The Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Areas (DCFTA) are linked with the EU Association Agreements negotiated separately with Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine. The DCFTAs allow these countries access to the European Single Market in selected sectors, while granting EU investors in those sectors the same regulatory environment in these countries as in the EU.

On 2 July 2021, the European Commission and the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy presented the Eastern Partnership: a Renewed Agenda for cooperation with the EU’s Eastern partners. This agenda is based on the five long-term objectives, with resilience at its core, as defined for the future of the Eastern Partnership in the Joint Communication Eastern Partnership policy beyond 2020: Reinforcing Resilience – an Eastern Partnership that delivers for all in March 2020. It is further elaborated in the Joint Staff Working Document Recovery, resilience and reform: post 2020 Eastern Partnership priorities. It will be underpinned by an Economic and Investment plan. The Joint Declaration of the Eastern Partnership Summit ‘Recovery, Resilience and Reform’ of 15 December 2021 reaffirms strong commitment to a strategic, ambitious and forward-looking Eastern Partnership.

In cooperation with its ENP partners, Eurostat has the responsibility ‘to promote and implement the use of European and internationally recognised standards and methodology for the production of statistics necessary for developing and monitoring policy achievements in all policy areas’. Eurostat undertakes the task of coordinating EU efforts to increase the statistical capacity of the ENP countries. Additional information on the policy context of the ENP is provided here.

Direct access to

Books

Factsheets

Leaflets

- Basic figures on the European Neighbourhood Policy — East countries — 2020 edition

- Basic figures on the European Neighbourhood Policy — East countries — 2019 edition

- Basic figures on the European Neighbourhood Policy — East countries — 2018 edition

- Basic figures on the European Neighbourhood Policy — East countries — 2016 edition

- Basic figures on the European Neighbourhood Policy — East countries — 2015 edition

- Basic figures on the European Neighbourhood Policy — East countries — 2014 edition

- International trade for the European Neighbourhood Policy — East countries — 2016 edition

- European Neighbourhood Policy-East countries — Statistics on living conditions — 2015 edition

- European Neighbourhood Policy — East countries — Key economic statistics — 2014 edition

- European Neighbourhood Policy — East countries — Labour market statistics — 2014 edition

- European Neighbourhood Policy — East countries — Youth statistics — 2014 edition

- International trade (enpe_ext)

- European Neighbourhood Policy East Countries Trade in goods by SITC product group (enpe_ext_sitc)

- Trade balance (enpe_ext_bal)

- Share of European Neighbourhood Policy East Countries in European Union 27 trade (enpe_ext_intro)

- International trade in goods - aggregated data (ext_go_agg)

- International trade in goods - long-term indicators (ext_go_lti)

- International trade (ext_go_lti_int)

- International trade of EU, the euro area and the Member States by SITC product group (ext_lt_intertrd)

- EU trade by Member State, partner and product group (ext_go_lti_ext)

- Intra and Extra-EU trade by Member State and by product group (ext_lt_intratrd)

- International trade (ext_go_lti_int)

- International trade in goods - long-term indicators (ext_go_lti)

- Eastern European Neighbourhood Policy countries (ENP-East) (ESMS metadata file — enpe_esms)

- International trade in goods statistics — European Union (ESMS metadata file — ext_go_agg_esms)

- Quality report on European statistics on international trade in goods — 2016-2019 data — 2020 edition

- User guide on European statistics on international trade in goods — 2020 edition

- European External Action Service — European Neighbourhood Policy

- Joint Communication JOIN(2020) 7 final: Eastern Partnership policy beyond 2020: Reinforcing Resilience - an Eastern Partnership that delivers for all (18 March 2020)

- Joint Staff Working Document SWD(2021) 186 final: Recovery, resilience and reform: post 2020 Eastern Partnership priorities (2 July 2021)

- Joint Declaration of the Eastern Partnership Summit: ‘Recovery, Resilience and Reform’ (15 December 2021)

- European Commission — trade policy