Archive:Being young in Europe today - demographic trends

Data extracted in December 2017

Planned article update: June 2021

Highlights

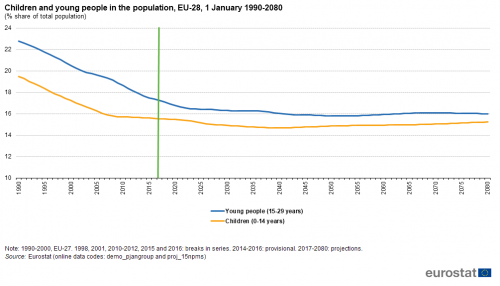

Nearly one third of the EU population were under the age of 30 in 2016, with children aged 0-14 years accounting for a 16 % share of the EU population and young people aged 15-29 years for 17 %.

By 2016 there were 98 million people in the EU aged 65 years and more, compared with 80 million children.

There were more male than female children in the EU in 2016, with boys accounting for 51 % of the population aged 0-14 years.

This is one of a set of statistical articles that forms Eurostat’s flagship publication Being young in Europe today. It presents a range of demographic statistics for children (defined here as those aged 0-14 years) and young people (defined here as those aged 15-29 years) across the European Union (EU). A paper edition of the publication was also published in 2015. In late 2017, a decision was taken to update the online version of the publication (subject to data availability). As Europe continues to age, the historical shape of its age pyramid has moved away from a triangle (associated with an expanding population) and has been reshaped, with a smaller proportion of children and young people and an increased share of elderly persons.

The analysis begins with a set of basic statistics that portray the existing demographic structure of the EU-28, focusing on the relative importance of children and young people. It continues with some international comparisons, which highlight the relatively small share of the EU’s population that is accounted for by children and young people when compared with many other countries across the globe. It then moves on to examine a range of demographic phenomena that may be linked to the falling share of children and young people in the EU’s population, such as: the rising median age of the population; the low level of fertility rates; the increased longevity of the EU’s population; and the potential impact that these drivers of demographic change could have on the EU’s population in the coming decades.

Full article

Europe's demographic challenge

EUROPE’S DEMOGRAPHIC CHALLENGE

Numerous studies have concluded that the EU’s population is likely to shrink in the coming decades as a result of a prolonged period of relatively low fertility rates, although this also depends, at least to some degree, on migratory patterns. The falling share of children and young people in the total population could result in labour market shortages in specific countries/regions and in particular occupations. By contrast, life expectancy (for both men and women) in the EU continues to rise while the baby-boom generation [1] is in the process of moving into retirement. As such, the number and share of the elderly in the total population continues to increase. This will probably drive demand for a range of specific services (for example within the areas of social and health care) catered to the needs of the (very) old. These two changes at either end of the age spectrum will affect the structure of the EU’s population and could lead to a number of challenges, for example:

- how to encourage sustainable economic growth during a period when the number and proportion of working-age people will decline; a lower number of working-age people could lead to a reduction in revenue-raising powers, for example, from income tax and social security contributions;

- how to safeguard social welfare models, such as pensions and healthcare, if there are a growing number of (very) old people who are making increasing demands on these systems.

Past, present and future demographic developments of children and young people

Just under 167 million children and young people in the EU-28 in 2016

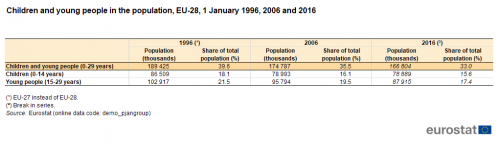

Figures for 2016 indicate that there were just over 510 million inhabitants in the EU-28. Of these, 79 million were children aged 0-14 years, which was 9 million fewer than the number of young people aged 15-29 years. As such, nearly one third of the EU-28’s population — just under 167 million inhabitants — were under the age of 30 in 2016, with children accounting for a 15.6 % share of the EU-28’s population and young people for a slightly higher share, 17.4 %.

The combined share of children and young people (those aged 0-29 years) in the EU’s population fell from 39.6 % in 1996, through 35.5 % in 2006, to 33.0 % by 2016 (see Table 1). The rate of change in the number of young people was relatively constant over the period under consideration, while the decline in the proportion of children was much less during the period 2006-2016 than during the period 1996-2006 (as a result of a modest upturn in fertility rates).

As the share of children and young people in the EU’s population decreased, the relative importance of the elderly aged 65 years and over grew. The proportion of elderly persons in the EU’s population climbed at a steady pace from 14.9 % of the population in 1996, through 16.8 % in 2006 to reach 19.2 % at the end of the time series. The pace of demographic ageing quickened somewhat as the relative share of the elderly rose at a slightly faster pace between 2006 and 2016 than it had done between 1996 and 2006.

The number of elderly people in the EU exceeded the number of children for the first time in 2005

To give some idea of the speed of demographic change, there were 86.5 million children in the EU-27 in 1996 compared with 71.3 million elderly persons. By 2004 the gap between the number of children and the number of elderly persons had narrowed considerably to 0.4 million across the EU-28, with 81.0 million children and 80.6 million elderly persons. By 2005, there were, for the first time, more elderly people (81.9 million) than children (80.4 million) in the EU-28. The growth in the number of elderly people continued in the following years, while the number of children continued to fall until a low of 78.9 million was reached in 2009, after which it started to increase again. By 2016 there were 97.7 million people in the EU-28 aged 65 years and more, compared with 79.5 million children.

This rapid acceleration in the share of the elderly was accompanied by an increase in the share of persons aged 30-64 years. People in this age group accounted for 45.5 % of the EU-27’s population in 1996 rising to 47.7 % of the EU-28’s population by 2006 and increasing slightly further to reach 47.9 % by 2016; these increasing shares may be attributed to the impact of ageing among the baby-boomer generation, as those born in the 1960s accounted for a growing share of the EU’s working-age population. Population projections suggest that the share of the working-age population in the total population will start to decrease in the coming years, as more people from the baby-boomer generation move into retirement.

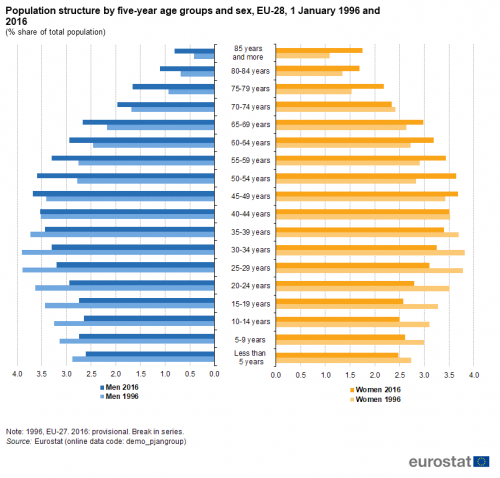

Reshaping the population pyramid: a decreasing share of children and young people

Figure 1 presents the EU’s age pyramid (a graphical representation of its population structure), with information shown for the proportion of men and women within each five-year age group as a share of the total population. The two pyramids, for 1996 and 2016, provide evidence of the ageing of the EU’s population: there is a clear bump present in both pyramids, which can be associated with the tail end of the baby-boomer generation. In 1996, the highest share of the population was accounted for by those aged 25-29 or 30-34 years — in other words, people born mainly during the 1960s. By 2016, this same group had aged an additional 20 years and moved into the age group of persons aged 45-49 or 50-54 years; the age group 45-49 years accounted for the highest share of the population among any of the five-year age groups.

In 2016, the three five-year age groups that together cover the aggregate for children (those aged 0-4 years, 5-9 years and 10-14 years) as well as the youngest five year age group among young people (in other words the age group 15-19 years) accounted for the smallest shares of the EU-28 population in terms of five-year age groups, apart from the elderly (see below for more details).

Figure 1 shows a fall in the relative share of children and young people in the total EU population between 1996 and 2016. Nevertheless, the fall is greater for the three five-year age groups covering young people (15-29 years) than for children. This may be linked in part to a development over recent decades of women having children at a later age, so initially bringing down the number of births which subsequently stabilised (or rose at a modest pace).

The other notable difference between the pyramids for 1996 and 2016 is the increasing share of the elderly in the total population. This was particularly true among the oldest group of women (those aged 85 or above), as longevity increased at a rapid pace over the last two decades.

Boys outnumbered girls in the EU

There were more male (than female) children in the EU-28 in 2016; boys accounted for 51.3 % of the population aged 0-14 years. This is consistent with the time series for births which shows higher numbers of boys being born than girls. There were also more young men aged 15-29 years than there were young women, although the difference across the EU-28 was narrower than for children, as young men made up 51.1 % of all young people in 2016.

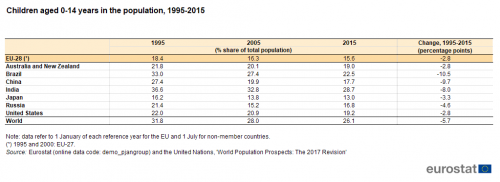

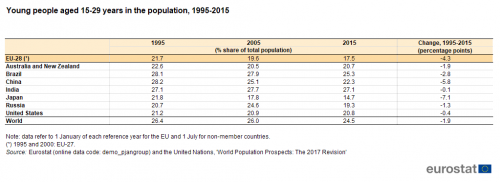

The share of children and young people in the EU’s population was considerably lower than the world average

Children and young people (0-29 years) accounted for just under one third (33.1 %) of the EU-28 population in 2015, while their share in the world population was considerably higher, at 50.6 % — see Tables 2 and 3. Children accounted for 15.6 % of the EU-28’s population in 2015, which was 10.5 percentage points lower than the world average, while young people represented 17.5 % of the EU-28’s population, which was slightly closer to the world average, 7.0 points lower. The relative importance of children and young people across the world was influenced, to some degree, by relatively high birth rates in Africa and some parts of Asia.

Source: Eurostat (demo_pjangroup) and the United Nations, 'World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision'

Source: Eurostat (demo_pjangroup) and the United Nations, 'World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision'

The relative weight of children and young people in the EU-28’s population was considerably lower than in many of the industrialised and rapidly emerging economies presented in Tables 2 and 3. For example, children accounted for 28.7 % of the total population in India, more than one fifth (22.5 %) of the population in Brazil and close to one fifth (19.2%) of the population in the United States in 2015. There were, however, a couple of exceptions: as the relative share (13.0 %) of children in the Japanese population was lower than the EU-28 average, while in Russia the share (16.8 %) in 2015 was only 1.2 points higher than in the EU-28, having been lower than in the EU-28 in 2005.

Signs that the fall in birth and fertility rates is spreading to other developed and emerging economies

Worldwide, there was a general decline in the relative share of children in the global population between 1995 and 2015. Their share decreased by 5.7 points, which was a much larger decline than in the EU-28 (-2.8 points). The largest decreases (among those countries shown in Table 2) were observed in Brazil and China, where the share of children in the total population fell by 10.5 and 9.7 points during the period under consideration. With the exceptions of the United States, and Australia and New Zealand, the decline in the share of children in the total population was more substantial for each of the countries shown in Table 2 than for the EU-28.

The global share of young people in the world’s population declined by a relatively small amount (down by 0.2 points) over the period 1995-2015. The share of young people remained relatively stable in the majority of the countries shown in Table 3, as Japan and China were the only countries where the share fell faster than it did in the EU-28. Japan was the only country shown in Table 3 to record a share of young people in its total population (14.7 %) that was lower than the EU-28 average (17.5 %) in 2015.

The information presented in Tables 2 and 3 confirms that the pattern of decreasing birth and fertility rates observed across the EU-28 and Japan appears to be in the process of establishing itself across a range of other industrialised and emerging economies. As this is often a relatively new phenomena, the most rapid changes in population structure are initially apparent among populations of children, although in the coming years the lower number of children will gradually impact upon the number of young people too, as the effect of lower birth and fertility rates moves up through each national population pyramid.

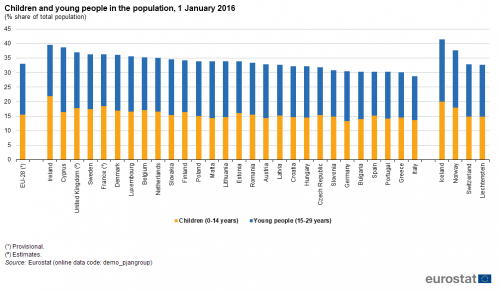

Ireland and Cyprus: the most youthful Member States

Ireland and Cyprus were the most youthful nations in the EU-28, as people aged 0-29 years accounted for nearly 4 out of every 10 inhabitants in 2016 (Ireland 39.5 % and Cyprus 38.7 %). At the other end of the spectrum, the share of children and young people in the total population was lowest in Italy (28.8 %).

Children accounted for more than one in five (21.9 %) of the Irish population in 2016 — the highest share among the EU Member States — while France (18.5 %) and the United Kingdom (17.7 %) recorded the second and third highest shares. By contrast, children accounted for 13.2 % of the German population in 2016, while they also represented a relatively small share of the population in Italy (13.7 %).

Cyprus (22.2 %) recorded the highest proportion of young people in its population in 2016. Furthermore, in Cyprus children accounted for a much lower share of the total population than did young people (5.8 points less), suggesting that the Cypriot birth and fertility rates had fallen rapidly over recent decades. At the other end of the scale, the shares of young people in the total populations of Italy and Spain fell to 15.1 %, while there was also a comparatively low share in Greece (15.6 %).

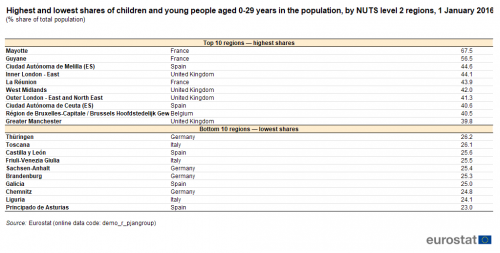

Children and young people accounted for a low share of the population in many eastern German and northern Italian and Spanish regions

While there was a considerable degree of variation in the share of children and young people between the EU Member States, the differences were even more pronounced across Europe’s regions. Among NUTS level 2 regions, Mayotte and Guyane (two French overseas departments) were the only regions in the EU where children and young people represented more than half of the population in 2016, some 67.5 % and 56.5 % of their total number of inhabitants being aged 0-29 years. The fifth highest share was also recorded in a French overseas department, namely, Réunion (43.9 %), while the Spanish autonomous city regions of Melilla (44.6 %) and Ceuta (40.6 %) had the third and eighth highest shares. Alongside these five regions from outside of continental Europe, the top 10 regions with the highest shares of children and young people included four British regions (including two in the capital city of London and the urban centres of West Midlands and Greater Manchester) and the Belgian capital region. More generally, the regions which feature near the top of the ranking with the highest shares of children and young people in their respective populations were often from France, Ireland, the United Kingdom or Belgium.

Source: Eurostat (demo_r_pjangroup)

By contrast, those regions with the lowest shares of children and young people in their total number of inhabitants included the northern Spanish regions of Principado de Asturias, Galicia, and Castilla y León, the northern Italian regions of Liguria and Friuli-Venezia Giulia, the central Italian region of Toscana, and the eastern German regions of Chemnitz, Brandenburg, Sachsen-Anhalt and Thüringen. These regions were quite representative of a more general pattern, as many of the regions at the bottom end of the ranking were from eastern Germany, northern Spain and various parts of Italy, with children and young people often accounting for less than 27 % of the total population.

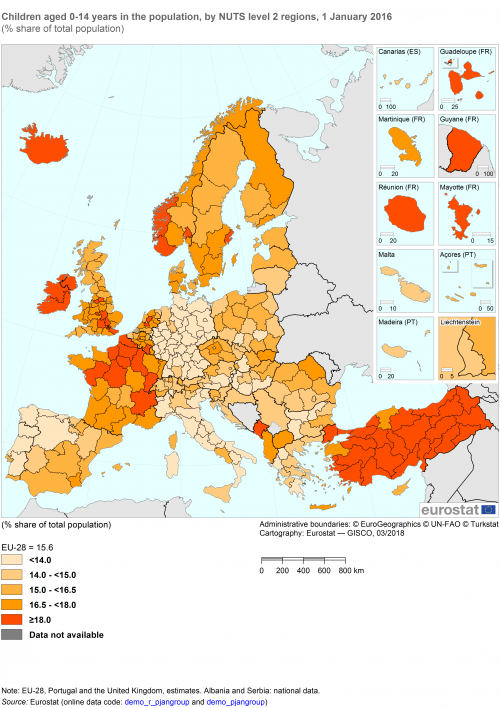

Outside of French overseas departments and Spanish autonomous cities, the two Irish regions had the highest shares of children in their populations

Map 1 presents the relative share of children in the regional populations of NUTS level 2 regions in 2016. Aside from the French overseas departments of Mayotte (44.1 %), Guyane (33.5 %) and La Réunion (23.6 %) and the Spanish Ciudad Autónoma de Melilla (24.0 %), the highest shares were recorded for the two Irish regions of Border, Midland and Western (22.6 %) and Southern and Eastern (21.7 %). There were three other regions in the EU-28 where children represented more than one fifth of the regional population in 2016: Ciudad Autónoma de Ceuta (the second autonomous Spanish city), and the British regions of Outer London - East and North East and West Midlands.

Source: Eurostat (demo_r_pjangroup) and (demo_pjangroup)

Source: Eurostat (demo_r_pjangroup) and (demo_pjangroup)

At the other end of the range, the Spanish region of Principado de Asturias recorded the lowest share of children (11.1 %). In line with the general patterns observed at a national level, some of the regions with the lowest shares of children were located in Germany and Italy: for example, Saarland (11.6 %), Sachsen-Anhalt (11.7 %), Chemnitz (12.0 %) and Thüringen (12.2 %); Liguria (11.5 %), Molise (11.7 %) and Sardegna (11.8 %).

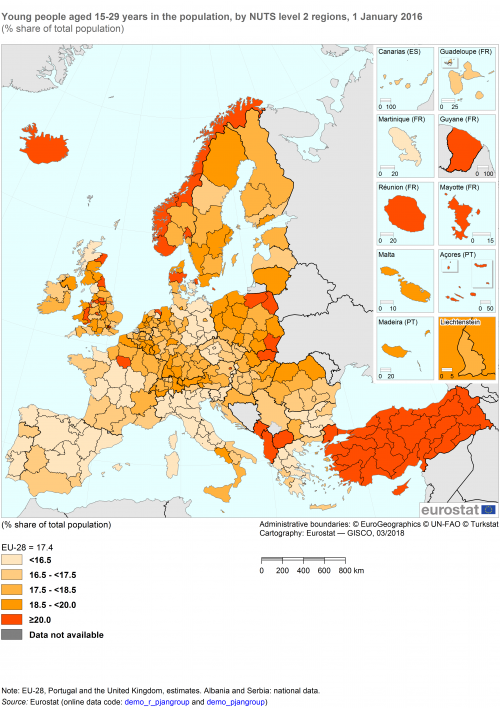

Inner London - East had the highest share of young people

Map 2 presents a similar set of information to the previous map, but this time based on the share of young people in the regional population (again for NUTS level 2 regions). Inner London - East had the highest share of young people (25.5 %) in 2016, which can probably be explained not only by its above average birth rate, but also because of the appeal of this city to younger generations; the presence of numerous higher education institutions may also have an impact on the proportion of young adults living in this region. The next three highest shares were recorded in the French overseas regions of Mayotte (23.3 %) and Guyane (23.0 %) and in Inner London - West (23.1 %). They were followed by the Dutch region of Groningen, Cyprus (a single region at NUTS level 2), the Slovakian region of Východné Slovensko and two more British regions (West Midlands and South Yorkshire) where this share was at least 21.0 %.

By contrast, the share of young people was particularly low in the same regions where the share of children was low, principally in northern and central parts of Italy, northern Spain and eastern Germany. The lowest shares were recorded in the Italian region of Liguria (12.7 %) and the Spanish region of Principado de Asturias (11.9 %).

The proportion of children and particularly young people in the total population of the EU-28 is projected to fall slightly in the coming decades

According to the main scenario of EUROPOP2015, which corresponds to the latest Eurostat population projections round, by 2080 the number of children and young people in the EU-28 is likely to be 162.0 million, which is 4.8 million less than in 2016. Although the EU-28 total population is projected to keep growing through to 2045, reaching 529.1 million, the share of children and young people in the total projected population will decrease from 33.0 % in 2016 to 30.6 % in 2043. Then, from 2043 to 2080, the share of children and young people is projected to slowly and almost continuously increase (reaching 31.2 % in 2080), therefore remaining below its 2016 level.

EUROSTAT’S POPULATION PROJECTIONS

Population projections give a picture of what the future population may look like based on a set of assumptions for fertility and mortality rates as well as for migration.

EUROPOP2015 is a set of population projections produced by Eurostat based on the cohort-component method. These are essentially ‘what-if’ scenarios, providing information about the likely future size and structure of the population at national level, by sex and single-years of age. EUROPOP 2015 covered the time period from 1 January 2015 to 1 January 2081.

The projections presented in this article relate to what is referred to as the ‘baseline projection’, based on a set of assumptions relating to future fertility, mortality and net international migration. This main scenario is complemented by five sensitivity tests that are based on the following characteristics: lower fertility; lower mortality; higher migration; lower migration; no migration.

Figure 3 shows the share of children and young people in the projected population of the EU-28 up to and including the year 2080. Having already fallen from 19.5 % in 1990 to 15.6 % by 2016, the share of children is projected to decrease further to a relative low of 14.7 % by 2036-2044, followed by a slight increase up to 15.2 % by 2080.

The projected development of the share of young people in the EU-28’s total population shows an initial decline followed by a small recovery and then a period of relative stability until 2080. From 22.8 % of the total EU-28 population in 1990, the population aged 15-29 years fell to 17.4 % by 2016 and is projected to decrease to 15.8 % of the total population between 2048 and 2057. The share of young people is then projected to reach 16.1 % by 2066, and then remain at 16.0-16.1 % through to 2080.

Changes in numbers of children and young people: causes and consequences

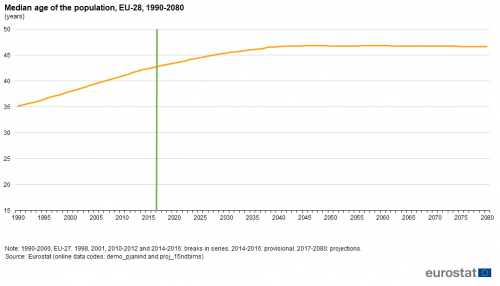

Median age — the greying of the EU’s population

Ageing is one of the EU’s main demographic challenges which may result in considerable political, economic, budgetary and social challenges. The median age of the EU-28 population has risen in recent years as a direct consequence of two principal factors: a reduction in the share of children and young people in the total population (resulting from lower fertility rates and women giving birth to fewer children at a later age in life) and a gradual increase in life expectancy that has led to increased longevity.

HOW TO DETERMINE IF A POPULATION IS AGEING?

The ageing, or greying, of the EU’s population can be measured by an analysis of the median age of its population. The median age of the population is the age that divides a population into two numerically equal groups; that is, with half the people younger and half older. In other words, if all of the people in the EU were ranked according to their age, the person standing in the middle of the line dividing those into two equal groups would have the median age.

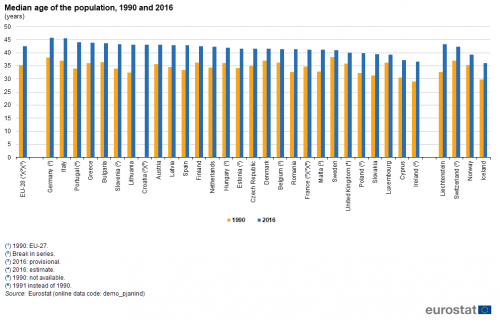

The median age of the EU population rose, on average, by three to four months each year over the last two decades

The median age of the EU-28 population was 42.6 years in 2016, having risen at a relatively rapid and consistent pace from 35.2 years in 1990 (for the EU-27), as shown in Figure 4. Eurostat’s latest projections indicate further increases in the median age during the coming decades, initially at a slightly slower rate and thereafter at a much slower rate. The median age of 43.0 years will be passed by 2018, 44.0 years by 2023, 45.0 years by 2028 and by 2034 the median age is projected to reach 46.0 years. The peak median age is projected to reach 46.8 years by 2045, and is projected to then remain within the range of 46.6-46.8 years through to 2080.

At a national level, the median age of the EU Member States in 2016 was lowest in the relatively youthful societies of Ireland (36.6 years) and Cyprus (37.2 years), while Luxembourg, Slovakia, Poland and the United Kingdom were the only other EU Member States to record median ages of 40.0 years or less. By contrast, there was a more rapid greying of society in Germany, where the median age was 45.8 years, while Italy (45.5 years) was the only other EU Member State to record a median age that was over 44.0 years.

The median age of the population within each EU Member State rose between 1990 and 2016. This ageing of the population was particularly stark in Lithuania and Portugal, where the median age rose by more than 10.0 years over the period under consideration, while there were increases of more than 9.0 years in Spain and Slovenia. By contrast, the median age of the population rose in Sweden and Luxembourg at a relatively slow pace, up by 2.5 and 3.0 years respectively between 1990 and 2016 — see Figure 5.

Life expectancy — people are living longer

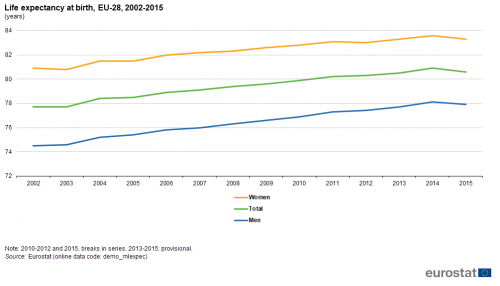

As noted above, greater longevity is one of the principal reasons why there has been an increase in the median age of the EU’s population. Between 2002 and 2015 there was an increase of nearly 3.0 years in life expectancy at birth (see Figure 6). The life expectancy of men increased at a somewhat faster pace than that of women, rising by 3.4 years compared with an increase of 2.4 years for women. These increases in life expectancy may be attributed to a range of factors, including medical progress and different types of health and community/social care, a general increase in health education/awareness, or people making different lifestyle choices (for example, stopping smoking, reducing alcohol intake, paying more attention to their diet, or exercising more) [2]. Furthermore, there has also been a gradual change in workplace occupations, whereby fewer people (in particular men) are employed in labour-intensive or dangerous activities, for example, agriculture, mining or heavy manufacturing industries.

Life expectancy steadily rising in the EU

The EU’s future population size and age structures will, to some degree, be determined by the pace at which life expectancy continues to increase. While higher levels of life expectancy and increased longevity result in a higher median age across the population, at the other end of the age spectrum the fertility rate has the potential to provide a counterbalance to the on-going ageing process — this is analysed in more detail in the next section.

Fertility rates — less children are being born

MEASURING FERTILITY

The total fertility rate represents the number of children that would be born to a woman if she were to live to the end of her childbearing years and bear children in accordance with the current age-specific fertility rates.

Age-specific fertility rates are computed as the ratio of the number of live births from women of a given age to the number of women of the same age exposed to childbearing (usually estimated as the average number of women in that year).

The replacement level represents the average number of live births per woman that would keep the population level stable and its age structure unchanged (in the absence of migratory flows or any change in life expectancy). It is generally agreed that the replacement level is about 2.1 children per woman in developed world economies.

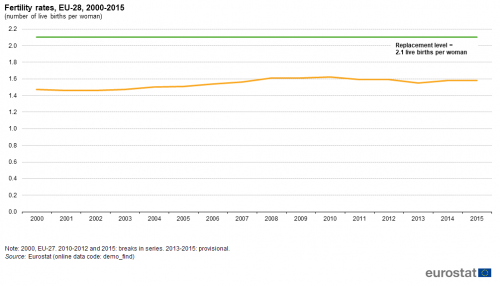

Figure 7 shows that while fertility rates in the EU-28 rose at a modest pace during the period 2000-2008, they remained well below the replacement level. Having peaked between 2008 and 2010 in the range of an average of 1.61-1.62 children, the fertility rate subsequently fell by a small margin, perhaps reflecting economic hardships and a decline in real incomes in the period following the global financial and economic crisis. In 2013, the EU-28 fertility rate was down to 1.55 children before increasing to 1.58 children in 2014 and 2015.

The general increase of the fertility rate during the period 2000-2008 may, in part, be attributed to a catching-up process, following a postponement of the decision to have children [3]; when women postpone giving birth until later in life, the total fertility rate first decreases and then subsequently recovers.

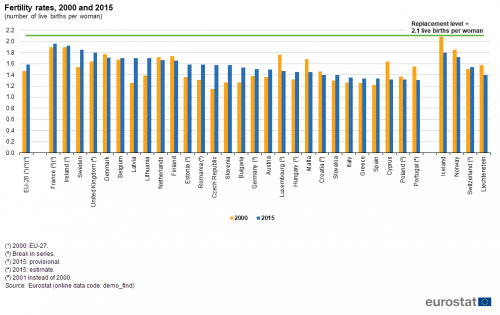

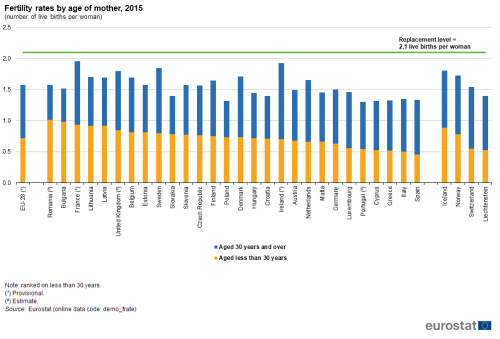

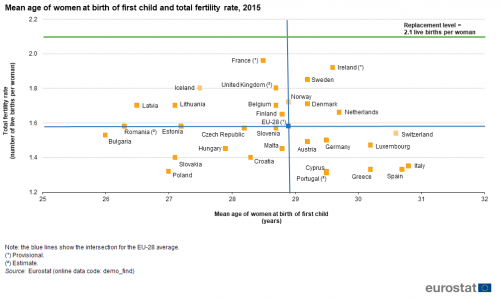

Ireland and France: the highest fertility rates

Among EU Member States, the highest fertility rates in 2015 were recorded in France and Ireland, with rates of 1.96 and 1.92 live births per woman. Figure 8 shows they were followed by Sweden (1.85 live births per woman) and the United Kingdom (1.80 live births per woman). The lowest fertility rates were registered in Portugal (1.31 live births per woman), Poland, Cyprus (both 1.32 live births per woman), Spain, Greece (both 1.33 live births per woman) and Italy (1.35 live births per woman).

Looking at women aged less than 30 years, their fertility rate in the EU-28 was 0.72 live births per woman in 2015, which was slightly less than half of the EU-28 total fertility rate that year (1.58 live births). This means that on average in the EU-28 just under half (46 %) of all babies were born to mothers who were below the age of 30.

Among EU Member States, Romania recorded the highest fertility rate for women aged less than 30 (with 1.02 live births per woman), followed by Bulgaria (0.99 live births per woman). By contrast, Luxembourg, Portugal, Cyprus, Greece, Italy and Spain recorded the lowest fertility rates for women aged less than 30 (with fewer than 0.60 live births per woman).

In Bulgaria and Romania, the fertility rate of women aged less than 30 corresponded to more than three fifths of the national fertility rate in 2015. By contrast, the fertility rate of women aged less than 30 represented less than 40 % of the national fertility rate in Spain, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg and Greece, meaning that less than 40 % of babies in these countries were born to mothers aged less than 30.

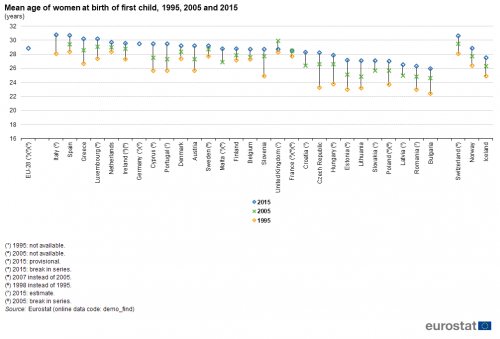

The mean age of women giving birth to their first child was over 30 years in Luxembourg, Greece, Spain and Italy in 2015

The mean age of women at the birth of their first child increased across all EU Member States in the last two decades. This can be explained, in particular, by a higher proportion of women continuing their studies into higher education, a larger proportion of women entering and remaining in the workforce, as well as changes in traditional family units (for example, less people getting married and people getting married later) [4].

Figure 10 provides information on the mean age of women at first childbirth. There were four EU Member States where the mean age of women at the birth of their first child was above 30 years in 2015: Luxembourg, Greece (both 30.2 years), Spain (30.7 years) and Italy (30.8 years). By contrast, the lowest mean ages for women at the birth of their first child were recorded in Latvia (26.5 years), Romania (26.3 years) and Bulgaria (26.0 years).

The average age of women when giving birth to their first child rose in each of the EU Member States (for which data are available) on the basis of a comparison between 1995 and 2015. This pattern was particularly pronounced in eastern and Baltic Member States, the largest increases being recorded in the Czech Republic (4.9 years higher), followed by Estonia (4.2 years) and Hungary (4.1 years), although it should be noted that there is a break in series for both Estonia and Hungary. By contrast, the pace of change was generally much slower in other parts of the EU, especially in those Member States where the average age of giving birth to a first child was already relatively high. The smallest increase was recorded in the United Kingdom, where the mean age of women at the birth of their first child rose by 0.4 years between 1995 and 2015, with an increase of 0.8 years recorded in France between 1998 and 2015 (note there is a break in series).

There appears to be little evidence to support the view that higher fertility rates may be expected in those EU Member States where the mean age of women at the birth of their first child was low. Rather, while women in eastern EU Member States were more likely to give birth at a relatively young age, they were also more likely to have fewer children, as their total fertility rates were below the EU-28 average with the exception of Romania where the rate was the same as the EU-28 average.

Source: Eurostat (demo_find)

By contrast, Figure 11 shows that the EU Member States that had fertility rates that were closest to the replacement level were diverse, as in some cases women, on average, gave birth to their first child at an age above the EU average (for example in Ireland and Sweden) and sometimes at an earlier age (for example, France and the United Kingdom). The relatively small group in the top right quadrant of Figure 11 — with above average fertility rates and above average mean age of women at the birth of their first child — was composed of EU Member States from northern and western Europe, as was the slightly larger group in the top left quadrant that also had above average fertility rates.

The bottom right quadrant of Figure 11 contains most of the southern EU Member States (although not Malta), as well as Germany, Austria and Luxembourg. These Member States were characterised by women giving birth to their first child at a relatively late age and by relatively low fertility rates.

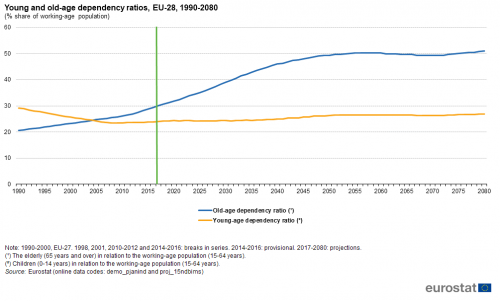

Dependency ratios — an increasing responsibility for those of working age

Age dependency ratios can be used to analyse the potential support that may be provided to children and to the elderly by people of working age. In 2016, the EU-28 young-age dependency ratio was 23.9 %, while the old-age dependency ratio was 29.3 %. This difference of more than 5 points is likely to increase in the coming years, as the proportion of elderly people in the population rises in the EU-28, while the share of children will continue to fall before stabilising (as presented above).

AGE DEPENDENCY RATIOS

The young-age dependency ratio is the ratio of persons aged 0-14 years divided by the number of persons conventionally considered to be of working age (15-64 years).

The old-age dependency ratio is the ratio of the number of persons conventionally considered to be economically inactive due to retirement (those aged 65 years and over) divided by the number of persons aged 15-64 years.

The size of the working-age population in the EU-28 will fall once the baby-boom generation have completed their move into retirement. As the number of people in the working-age population declines and the number of children is likely to remain relatively unchanged, population projections suggest that the young-age dependency ratio will start to rise, while the number of elderly people (especially those aged 85 years and over) will increase at a rapid pace in the coming decades, such that they will account for a considerably larger share of the total population.

Figure 12 shows the development of age dependency ratios and their projected path from 1990 until 2080, and provides a clear picture of the challenges that lie ahead concerning how the projected working-age population will be able to support the young and the elderly.

Adding up the share of young and old-age people who will depend on the working-age population, today’s generation of children will face an increased burden in relation to supporting the remainder of the population as they move into work. For example, maintaining welfare systems, pension schemes and public healthcare systems is likely to pose a challenge, while the overall demand for services from such systems and schemes is likely to increase, due to the rising number of elderly people. As such, policymakers are concerned about how to ensure the long-term sustainability of public finances in the face of a declining share of economically active people.

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

The data presented in this article are principally drawn from Eurostat’s population statistics, and more specifically from a range of demography indicators at a national and regional level (providing information on the structure of populations), fertility measures, mortality patterns and population projections (EUROPOP2015).

In this article, persons aged 0-14 years are considered as children. Although there is no clear-cut definition of ‘youth’ or ‘young people’ since these terms are often used to describe the transitory phase between childhood and adult life, the EU’s youth strategy has confirmed that for statistical purposes the most useful definition is to cover persons aged 15-29 years. Demographic statistics have a wealth of information for these age groups, while they can also provide statistics at a more detailed level, for example, by five-year age groups (such as 10-14 years or 15-19 years).

Eurostat carries out annual collections of demography data from national statistical authorities, including statistics concerning population and vital events, the latter including for example live births, deaths, marriages and divorces. These data are used to compute and disseminate demographic indicators at national and regional levels. Population data refer to the situation on 1 January of the reference year and are generally based on the usual resident population.

Context

European Demography Forum

The EU frequently reviews and adapts its policies in relation to demographic challenges, such as the ageing population, relatively low birth and fertility rates, atypical family structures and migration.

The European Demography Forum (held in 2006, 2008, 2010 and 2013) gave policymakers, stakeholders and experts from all over Europe the opportunity to share their knowledge and discuss how to address demographic change. To underpin these debates, the European Commission presented a biennial European Demography Report; these set out a range of facts and figures concerning demographic change and discusses appropriate policy responses.

The fourth forum took place in 2013 and covered, among other issues:

- supporting youth opportunities;

- improving the work-life balance;

- enabling people to be active longer;

- successful inclusion of second-generation migrants;

- regions in rapid demographic and economic decline and inequalities within regions.

For more information: see here.

Direct access to

- Population (demo_pop), see:

- Population on 1 January by age group and sex (demo_pjangroup)

- Population on 1 January by age group, sex and NUTS 2 region (demo_r_pjangroup)

- Population (demo_pop) (ESMS metadata file — demo_pop_esms)

- Population change - Demographic balance and crude rates at regional level (NUTS 3) (demo_r_gind3) (ESMS metadata file — demo_r_gind3_esms)

Notes

- ↑ The baby-boomer generation is a demographic phenomenon describing a period marked by considerably higher than average birth rates within a certain geographical area. The baby-boomer generation is often used to refer to those people who were born post-World War II, between the years 1946 and 1970 in Europe and the United States.

- ↑ See ’Health at a glance 2017’ and Sassi, F. (2010), Obesity and the Economics of Prevention — Fit not Fat, OECD Publishing, Paris.

- ↑ ’Demography Report 2010’, European Commission, Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs & Inclusion and Eurostat.

- ↑ See ‘Why do people postpone parenthood? Reasons and social policy incentives’, Melinda Mills, Ronald R. Rindfuss, Peter McDonald, Egbert te Velde, 2011.