Archive:Europe 2020 indicators - introduction

This article is part of a set of statistical articles based on the Eurostat publication Smarter, greener, more inclusive - Indicators to support the Europe 2020 strategy, providing recent statistics on the EU's Europe 2020 strategy.

About this publication

In late 2013, Eurostat introduced a new type of ‘flagship publication’ with the aim of providing statistical analyses related to important European Commission policy frameworks or important economic, social or environmental phenomena. The purpose of the first of these flagship publications – entitled Smarter, greener, more inclusive? — Indicators to support the Europe 2020 strategy – was to provide statistical support for the Europe 2020 strategy and to back-up the monitoring of its headline targets.

One year later, a new European Commission has been appointed, which will review the Europe 2020 strategy for the period 2015 to 2020. To this end, the Commission in March 2014 has published a stocktaking of the progress made up to the year 2014 [1]. Additionally, the Commission has run a public consultation to gather the views of stakeholders to help develop the strategy further. Eurostat is supporting this process by publishing an update of last year’s flagship publication, providing the latest statistical analyses of the Europe 2020 headline indicators [2].

The 2014 edition of ‘Smarter, greener, more inclusive?’ consequently builds on and updates last year’s Eurostat flagship publication. It presents official statistics produced by the European Statistical System (ESS) and disseminated by Eurostat. Impartial and objective statistical information is essential for evidence-based political decision-making and defines Eurostat’s role in the context of the Europe 2020 strategy. This role is to provide statistical and methodological support in the process of developing and choosing the relevant indicators to support the strategy, to produce and supply statistical data, and ensure its high quality standards.

The analysis in the publication is based on the Europe 2020 headline indicators chosen to monitor the strategy’s targets. Other indicators focusing on specific subgroups of society or on related issues that show underlying trends are also used to deepen the analysis and present a broader picture. The data used stem mainly from official ESS sources such as the EU Labour Force Survey (EU LFS) or the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU SILC) as well as from administrative sources.

The analysis in the 2014 edition of ‘Smarter, greener, more inclusive?’ looks into past trends, generally since 2002 or 2008, up to the most recent year for which data are available (2012 or 2013). Its purpose is not to predict whether the Europe 2020 targets will be reached, but to investigate the reasons behind the changes observed in the headline indicators. The publication includes references to analyses published by the European Commission on the future efforts required to meet the targets.

Data on EU-28 aggregates, individual Member States and, where available, on the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) and candidate countries, as well as the United States and Japan are presented. As described in the next section, the EU-wide targets have been translated into national targets by most Member States. In a few cases, maps presenting the different performances of Europe’s regions and their progress towards the national Europe 2020 targets are included, even though the targets only apply on a national level.

The publication is structured around the five Europe 2020 targets. Each is analysed in a dedicated thematic chapter. Data on the headline indicators and information on the Europe 2020 strategy are available on a dedicated section of Eurostat’s website: Europe 2020 indicators.

This introductory section presents the Europe 2020 strategy and the economic context in which it is embedded. An executive summary outlines the main statistical trends observed in the indicators. The five thematic chapters are followed by a ‘country profiles’ section. This describes how each Member State is progressing in relation to its national Europe 2020 targets.

The Europe 2020 strategy

The Europe 2020 strategy, adopted by the European Council on 17 June 2010 [3], is the EU’s agenda for growth and jobs for the current decade. It emphasises smart, sustainable and inclusive growth as a way to overcome the structural weaknesses in Europe’s economy, improve its competitiveness and productivity and underpin a sustainable social market economy.

The Europe 2020 strategy is the successor to the Lisbon strategy. The latter was launched in March 2000 in response to the mounting economic and demographic challenges for Europe at the dawn of the twenty-first century. The Lisbon strategy emerged as a commitment to increasing European competitiveness through a knowledge-based society, technological capacity and innovation.

Three key priorities

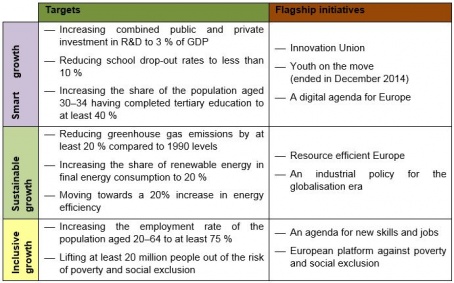

The Europe 2020 strategy puts forward three mutually reinforcing priorities to make Europe a smarter, more sustainable and more inclusive place to live:

- it envisions the transition to smart growth through the development of an economy based on knowledge, research and innovation.

- the sustainable growth objective relates to the promotion of more resource efficient, greener and competitive markets.

- the inclusive growth priority encompasses policies aimed at fostering job creation and poverty reduction.

In a rapidly changing world, these priorities are deemed essential for making the European economy fit for the future and for delivering higher employment, productivity and social cohesion. [4] Under the three priority areas the EU adopted five headline targets on employment, research and development (R&D), climate change and energy, education, and poverty and social exclusion. The targets are monitored using a set of eight headline indicators (including three sub-indicators relating to the multidimensional concept of poverty and social exclusion).

Each indicator falls within one of the three thematic priorities, as shown in Figure 1:

- The smart growth objective is covered by the indicators on innovation (gross domestic expenditure on R&D) and education (early leavers from education and training and tertiary educational attainment).

- The sustainable growth pillar is monitored by three indicators on climate change and energy (greenhouse gas emissions, share of renewable energy in gross final energy consumption and primary energy consumption).

- Inclusive growth is measured against the poverty or social exclusion headline indicator (combining three sub-indicators on monetary poverty, material deprivation and living in a household with very low work intensity) and employment rate.

For a detailed overview of the indicators see Table 1 in the Executive summary. The strategy objectives and targets are further supported by thematic flagship initiatives, as shown in Figure 1.

Five headline targets

The headline targets related to the strategy’s key objectives at the EU level are:

- Increasing the employment rate of the population aged 20¬–64 to at least 75 %.

- Increasing combined public and private investment in R&D to 3 % of GDP.

- Climate change and energy targets:

- Reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 20 % compared to 1990 levels.

- Increasing the share of renewables in final energy consumption to 20 %.

- Moving towards a 20 % increase in energy efficiency.

- Reducing school drop-out rates to less than 10 % and increasing the share of the population aged 30-34 having completed tertiary education to at least 40 %.

- Lifting at least 20 million people out of the risk of poverty or social exclusion.

These targets were initially defined in the ‘Commission communication Europe 2020 — A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth’ published on 3 March 2010[5] and adopted on 17 June 2010 by a European Council decision [6]. The recent Commission communication ‘Taking stock of the Europe 2020 strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth’ published on 5 March 2014 [7] introduced a slight rewording to the exact formulation of the targets. The formulation used in the 2014 edition of ‘Smarter, greener, more inclusive?’ follows this most recent communication.

The five headline targets are strongly interlinked, as shown in Figure 2. For example, higher educational levels help employability and progress in increasing the employment rate helps to reduce poverty. A greater capacity for research and development as well as innovation across all sectors of the economy, combined with increased resource efficiency, will improve competitiveness and foster job creation. Investing in cleaner, low-carbon technologies will help the environment, contribute to the fight against climate change and create new business and employment opportunities [8].

The EU headline targets have been translated into national targets. These reflect each Member State’s situation and the level of ambition they are able to reach as part of the EU-wide effort for implementing the Europe 2020 strategy. However, in some cases the national targets are not sufficiently ambitious to cumulatively reach the EU-level ambition. Fulfilment of all national targets in the area of employment, for instance, would bring the overall EU-28 employment rate up to 74 %, which is still one percentage point below the Europe 2020 target of 75 %. Similarly, even if all Member States met their national targets on R&D expenditure, the EU would still fall short of its target of 3 % R&D intensity, reaching only 2.6 % by 2020 [9].

Seven flagship initiatives

To ensure progress towards the Europe 2020 goals a broad range of existing EU policies and instruments are being harnessed, including the single market, the EU budget and external policy tools. In addition, the strategy has identified seven policy areas that serve as engines for growth and jobs and hence catalyse the procedure under each priority theme. These are put forward through the following seven flagship initiatives:

- ‘Innovation Union’ aims to create a more conducive environment for innovation by improving conditions and access to finance for research and development. Facilitating the transformation of innovative ideas into products and services is seen as the key to creating more jobs, building a greener economy, improving quality of life and maintaining the EU’s competitiveness on the global market.

- ‘Youth on the move’ is concerned with improving the performance and international attractiveness of Europe’s higher education institutions; to raise the overall quality of the education and training in the EU and assisting the integration of young people into the labour market. This aim is to be achieved through EU-funded study, learning and training programmes as well as through the development of platforms to assist young people in their search for employment across the EU.

- ‘A digital agenda for Europe’ aims to advance high-speed broadband coverage and internet structure, as well as the uptake of information and communication technologies across the EU.

- ‘A resource efficient Europe’ aims to facilitate the transition to a resource-efficient and low-carbon economy. This is to be achieved through support for increased use of renewable energy, development of green technologies, promotion of energy efficiency, modernisation of the transport, industrial and agricultural systems, preservation of biodiversity and regional development. The Resource Efficiency Scoreboard, comprising about 30 indicators, is disseminated via a dedicated section on Eurostat’s website [10].

- ‘An industrial policy for the globalisation era’ supports the development of a strong, diversified and resource-efficient industrial base, which is able to boost growth and jobs in Europe and successfully compete on the global market. It also sets out a strategy for promoting a favourable business environment by facilitating access to credit and internationalisation of small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

- ‘An agenda for new skills and jobs’ aims to advance reforms, which would improve flexibility and security in the labour market (‘flexicurity’); create conditions for mod-ernising labour markets and enhance job quality and working conditions. Further-more, it endorses policies aimed at empowering people, through the acquisition of new skills, through the promotion of better labour supply and demand matching and raise labour productivity.

- ‘European platform against poverty and social exclusion’ sets out actions for combating poverty and social exclusion by improving access to work, basic services, education and social support for the marginalised part of the population.

The headline targets and the flagship initiatives briefly defined above are described in more detail in the thematic chapters of this publication.

Taking stock of Europe 2020 – how to pursue smart, sustainable and inclusive growth?

In March 2014, the Commission published its communication ‘Taking stock of the Europe 2020 strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth’ [11]. It showed that the experience with the targets and flagship initiatives has been mixed: ‘The EU is on course to meet or come close to its targets on education, climate and energy but not on employment, research and development and poverty reduction’. The Commission concludes that while the targets have helped focus on longer-term, underlying features crucial to the future of the EU’s society and economy, their translation to the national level has highlighted several uncomfortable trends. These include a growing gap between the best and the least well performing Member States, a widening gap between regions within and across Member States, and growing inequalities in the distribution of wealth and income [12].

Looking at the aspects that will shape the strategy for the period 2015 to 2020, the Commission points out that ‘seeking to return to the growth “model” of the previous decade [before the crisis] would be both illusory and harmful’.

Instead, a revised Europe 2020 strategy will have to address a number of long-term trends affecting growth. According to the Commission’s stocktaking, these include [13]:

- Societal change: the two most prominent trends to be addressed are the ageing of the European population, leading to an ever increasing economic dependency [14], and the long-standing issue of effectiveness and fairness of the wealth produced and distributed through growth.

- Globalisation and trade: as the world’s largest trader in goods and services, and having in mind that in the next 10 to 15 years 90 % of the world’s growth will come from outside the EU, the EU needs to make sure that its companies remain competitive and are able to access new markets.

- Productivity developments and use of information and communication technologies (ICT): weak productivity growth is seen as one of the reasons for economic growth in Europe lagging behind that of other advanced economies over the last 30 years. The EU thus needs to boost productivity both as a source of growth and to address its shrinking working age population due to population ageing. In this regard, information and communication technologies (ICT) are considered crucial levers of growth and productivity in the EU.

- Pressure on resources and environmental concerns: during the twentieth century, the world’s fossil fuel use increased by a factor of 12, while extraction of material resources grew 34 times. Apart from the environmental impacts caused by this growing demand for resources, businesses are facing increasing costs for essential raw materials, energy and minerals, while the absence of security of supply and price volatility has a damaging effect on the economy as a whole. As a result, the EU needs to use its resources more efficiently. This would not only improve competitiveness and profitability but could also boost employment and economic growth.

The analyses presented in the 2014 edition of ‘Smarter, greener, more inclusive?’ take up many of the above mentioned challenges in the form of contextual indicators presented alongside the Europe 2020 headline indicators in the five thematic chapters dedicated to ‘Employment’, ‘R&D and innovation’, ‘Climate change and energy’, ‘Education’ and ‘Poverty’.

The European Semester: annual cycle of policy coordination

The success of the Europe 2020 strategy cruicially depends on Member States coordinating their efforts. To ensure this, the European Commission has set up an annual cycle of EU-level policy coordination known as the European Semester. Its main purpose is to strengthen economic policy coordination and ensure the coherence of the budgetary and economic policies of Member States with the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) and the Europe 2020 strategy.

The Annual Growth Survey (AGS), normally adopted by the Commission towards the end of the year, marks the start of the European Semester. It sets out overall economic, budgetary and social priorities at EU and national level, which are to guide Member States. Based on the AGS, each Member State has to develop plans for National Reform Programmes (NRPs) and Stability Convergence Programmes (SCPs). This period of integrated country surveillance starts before the first half of each year, when national economic and budgetary policies have still not been finalised. The aim is to detect inconsistencies and emerging imbalances and issue early warnings and recommendations in due course[15]. The NRPs and SCPs are submitted to the European Commission for assessment in April. At the end of June/July, country-specific recommendations are formally endorsed by the Council. These recommendations provide a timeframe for Member States to respond accordingly and implement the policy advice.

To ensure progress towards the Europe 2020 goals a broad range of existing EU policies and instruments are being harnessed, including the single market, the EU budget and external policy tools. Central to tackling the weaknesses revealed by the crisis and to achieving the Europe 2020 objectives of growth and competitiveness is the promotion of enhanced economic governance. The two important elements in this respect are the Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure (MIP) and the Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP) based on the Stability and Growth Pact.

The MIP is intended to monitor the build-up of persistent macroeconomic imbalances and serve as an early warning system. A MIP scoreboard of 11 indicators provides information for the identification of external and internal macroeconomic imbalances. Internal imbalances refer to public sector indebtedness, financial and asset market developments and other general trends such as private sector credit flows and unemployment. External imbalances are related to current account developments and trends in real effective exchange rates, share of world exports and nominal unit labour costs [16].

The EDP is a part of the corrective arm of the SGP. Its main purpose is to enforce compliance with budgetary discipline and ensure Member States take corrective actions in a timely and durable manner. The EDP operationalises limits on the budget deficit and public debt on the basis of the following thresholds enshrined in the Treaty: government deficit within 3 % of GDP and gross debt not exceeding 60 % of GDP without diminishing at a satisfactory pace. The procedure under the EDP starts when a Member State has either breached or is at risk of breaching one of the two thresholds, with special consideration sometimes also given to other factors. Within a period of six months (or three for serious breaches) countries placed in EDP need to take actions and implement recommendations to correct their excessive deficit levels. Member States that fail to do so within the predefined timeframe or deliver insufficient progress, become subject to certain sanctions and receive revised recommendations with an extended timeline.

Europe 2020 in a broader policy perspective

Policy framework of sustainable development

Sustainable development is a fundamental and overarching objective of the European Union, enshrined in its treaties since 1997. The concept aims to continuously improve the quality of life and well-being for present and future generations by linking economic development, protection of the environment and social justice. The renewed EU Sustainable Development Strategy from 2006 [17] describes how the EU will more effectively meet the challenges of sustainable development. The overall aim is to continually improve citizens’ quality of life by creating sustainable communities that manage and use resources efficiently and tap the ecological and social innovation potential of the economy, thus ensuring prosperity, environmental protection and social cohesion.

Unsustainable patterns of economic development, currently prevailing in society, have significant impacts on our lives. These include both socioeconomic and natural phenomena such as economic crises, intensified inequalities, climate change, depletion of natural resources and environmental degradation. The recent economic crisis has wiped out years of economic and social progress and exposed structural weaknesses in Europe’s economy. Meanwhile, in a fast moving world, long-term challenges, such as globalisation, pressure on resources and an ageing population, are intensifying.

The Europe 2020 strategy has been adopted as the EU’s answer to these challenges, building on the EU Sustainable Development Strategy, by focusing on the practical implementation of the EU’s overarching policy agenda for sustainable development. Due to their complexity and global scope, the above-mentioned challenges require a coherent and comprehensive response from the international community. In this respect, the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development held in Rio de Janeiro in June 2012 (also known as ‘Rio+20’) has played an important role in shaping a common global vision of an ‘economically, socially and environmentally sustainable future for the planet and for present and future generations’ [18]. The conference was a 20-year follow-up of the 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (the Earth Summit), which promoted the concept of sustainable development. Rio+20 recognised the transition to sustainable patterns of consumption and production, the protection of the natural resource base and poverty eradication as key requirements for achieving sustainable development.

Rio+20 also started a process for establishing universal sustainable development goals (SDGs) and agreed on a set of actions for mainstreaming the development and later realisation of these objectives. In its 2013 communication ‘A decent life for all: ending poverty and giving the world a sustainable future’ [19], the EU showed commitment to actively engage in the processes and work towards the implementation of the objectives agreed. The document proposes principles for an overarching framework that provides a coherent and comprehensive response to the universal challenges of poverty eradication and sustainable development in its three dimensions, with the ultimate goal of ensuring a decent life for all by 2030 [20].

In June 2014 the Commission published a follow-up of its ‘decent life’ communication from 2013, entitled ‘A decent Life for all: from vision to collective action’ [21]. Building on the existing EU position concerning the development of the SDGs, this new communication further elaborated key principles and set out possible priority areas and potential target topics for the ‘post-2015 framework’. ‘Statistics’ is one of the areas listed in the communication for which actions are taken that contribute to the implementation of Rio+20. This highlights the importance of official statistics for evidence-based political decision-making. As such, the communication calls for the further development of indicators on GDP and beyond in the EU (see next section), as well as further improve measurement of progress and ensure comparability on an international level.

Going beyond GDP

For many years, GDP — originally designed as a measure of macro-economic performance and market activity — has been used to assess a society’s overall well-being. The political consensus for using GDP as the only measure for societal progress has been declining over the past few years.

Most prominently, new approaches to measuring progress have been proposed in the report of the Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi Commission [22], in the European Commission’s communication ‘ GDP and beyond’ [23] and in the report of the ESS’s Sponsorship Group ‘Measuring Progress, Well-being and Sustainable Development’ [24].

In August 2009, the European Commission published the communication ‘ GDP and beyond — Measuring progress in a changing world’ which aims to improve indicators to better reflect policy and societal concerns. It seeks to improve, adjust and complement GDP with indicators that monitor social and environmental progress and to report more accurately on distribution and inequalities. It identifies five key actions for the short to medium term (see Box 1).

|

‘GDP and beyond’ key actions for the short to medium term

|

In September 2009, the Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi commission published its report on the ‘Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress’ [25] with 12 recommendations on how to better measure economic performance, societal well-being and sustainability (see Box 2).

In November 2011 the ESS Committee adopted the report by the ESS Sponsorship Group on ‘Measuring Progress Well-being and Sustainable Development’. This report translates the recommendations from the Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi Commission report and the European Commission’s communication ‘GDP and beyond’ into a plan for concrete actions for the ESS for better use of and improving existing statistics with a view to providing the most appropriate indicators. The report identifies about 50 concrete actions for improving and developing European statistics over the coming years. The ESS Committee has decided to work further on the following priority areas:

- Strengthening the household perspective and distributional aspects of income, consumption and wealth.

- Multidimensional measures of quality of life.

- Environmental sustainability.

The actions are an integral part of the European Statistical Programme [26] and they are gradually being implemented, resulting in new sets of indicators (for example ‘Quality of life’ [27]), in refining and specifying existing indicators (such as household adjusted disposable income per capita) and in extending national accounts to integrate environmental, social and economic accounting [28].

In August 2013, DG Environment published a Commission staff working document [29] summarising the results obtained in the context of the ‘GDP and beyond’ communication and its five key actions (see Box 1).

|

12 recommendations from the Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi commission 1. When evaluating material well-being, look at income and consumption rather than production. 10. Measures of both objective and subjective well-being provide key information about people’s quality of life. Statistical offices should incorporate questions to capture people’s life evaluations, hedonic experiences and priorities in their own survey. |

See also

Further Eurostat information

Publications

Main tables

Dedicated section

Methodology / Metadata

- Towards robust quality management for European Statistics - Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council COM(2011) 211 final.

Other information

- Regulation 223/2009 of 11 March 2009 on European statistics

External links

Notes

- ↑ European Commission, Taking stock of the Europe 2020 strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, COM(2014) 130 final, Brussels.

- ↑ See http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/europe_2020_indicators/headline_indicators.

- ↑ European Commission, Europe 2020 — A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, COM(2010) 2020 final, Brussels, 2010; European Council conclusions, 17 June 2010, EUCO 13/10, Brussels, 2010.

- ↑ European Commission, Europe 2020 — A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, COM (2010)2020 final.

- ↑ European Commission, Europe 2020 — A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, COM(2010) 2020 final, Brussels, 2010; European Council conclusions, 17 June 2010, EUCO 13/10, Brussels, 2010.

- ↑ European Council conclusions, 17 June 2010, EUCO 13/10, Brussels, 2010.

- ↑ European Commission, Taking stock of the Europe 2020 strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, COM(2014) 130 final, Brussels.

- ↑ European Commission, Europe 2020 — A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, COM(2010) 2020 final, Brussels, 2010 (p. 11).

- ↑ European Commission, Taking stock of the Europe 2020 strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, COM(2014) 130 final, Brussels (p. 12-16).

- ↑ See http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/europe_2020_indicators/ree_scoreboard

- ↑ European Commission, Taking stock of the Europe 2020 strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, COM(2014) 130 final, Brussels.

- ↑ European Commission, Taking stock of the Europe 2020 strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, COM(2014) 130 final, Brussels (p. 21).

- ↑ European Commission, Taking stock of the Europe 2020 strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, COM(2014) 130 final, Brussels (p. 8-11).

- ↑ Economic dependency is the ratio between the number of people not in employment and those who are; this ratio is expected to rise from 1.32 in 2010 to 1.47 in 2030.

- ↑ European Commission, The European Union Explained: Europe 2020: Europe’s Growth Strategy, 2012.

- ↑ European Commission, Eurostat, Macroeconomic Imbalances Procedure Scoreboard Headline Indicators, 2012, (p. 2).

- ↑ European Council, Review of the EU Sustainable Development Strategy (EU SDS) — Renewed Strategy, 10117/06, Brussels, 2006.

- ↑ European Commission, A decent life for all: ending poverty and giving the world a sustainable future, COM(2013) 92 final, Brussels, 2013 (p. 6).

- ↑ European Commission, A decent life for all: ending poverty and giving the world a sustainable future, COM(2013) 92 final, Brussels, 2013.

- ↑ European Commission, A decent life for all: ending poverty and giving the world a sustainable future, COM(2013) 92 final, Brussels, 2013 (p. 2).

- ↑ European Commission, A decent Life for all: from vision to collective action, COM(2014) 335 final.

- ↑ French president Nicolas Sarkozy in 2008 set up a high level Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress chaired by Joseph Stiglitz, Amartya Sen and Jean-Paul Fitoussi in order ‘to identify the limits of GDP as an indicator of economic performance and social progress’ and ‘to consider additional information required for the production of a more relevant picture’.

- ↑ European Commission, GDP and beyond — Measuring progress in a changing world, COM(2009) 433 final, Brussels, 2009.

- ↑ Final report of the ‘Sponsorship Group on Measuring Progress, Well-being and Sustainable Development’ adopted by the European Statistical System Committee in November 2011.

- ↑ Stiglitz, J.E., Sen, A., Fitoussi, J.-P., Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress, 2009.

- ↑ Regulation (EU) No 99/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 January 2013 on the European Statistical Programme 2013–17, Official Journal of the European Union 2013.

- ↑ See http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/gdp_and_beyond/quality_of_life/data/overview.

- ↑ See http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/environmental_accounts/introduction.

- ↑ European Commission, Commission staff working document ‘Progress on ‘GDP and beyond’ actions’, Volume 1 of 2, SWD(2013) 303 final, Brussels, 2013.