Archive:Labour market slack - unmet need for employment - quarterly statistics

Data extracted in April 2021

Planned article update: July 2021

Highlights

Since the beginning of 2020, the health crisis disrupted the economic activity in the European Union. Some people may have lost their employment, have lost the opportunity to start a new job or their contracts to be renewed or, were obliged to work fewer hours than expected.

The containment measures to limit the spread of the virus and their consequences on some businesses or schools, sometimes alternating closing and reopening, might also have changed the availability or the job search of people without work. Nevertheless, an individual is considered unemployed if he/she fulfils the ILO criteria that are precisely being without work, available to start working within two weeks and having actively sought employment. This means that only referring to unemployment might underestimate the entire unmet demand for employment, also called the labour market slack, especially during the health crisis. To better reflect this unmet demand, the labour market encompasses in addition to unemployed people, part-time workers who want to work more, people available to work and want to but who do not look for a job as well as people looking for a job but who are not immediately available.

The fourth quarter of 2020 confirmed the upturn in activity already initiated in the third quarter 2020, although to a different degree according to the country and the sectors of activity. However, as further explained, it is necessary to put this positive signs in perspective, specifically as regards the sharp drop recorded in the second quarter of 2020.

This article is based on quarterly and seasonally adjusted Labour Force Survey (LFS) data and complements with a more detailed approach the article on Key consequences of the COVID-19 crisis on the labour market specifically regarding the gender differences in the unmet demand for employment. It investigates the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on the whole labour market slack and provides an overview of its specific components. Both the European and the country approaches are presented in this article, which shows the effect of the COVID-19 crisis at the global EU level and at the national level in the respective Member States as well as in three EFTA countries (Iceland, Norway and Switzerland) and three candidate countries (North Macedonia, Serbia and Turkey).

This article is part of the online publication Labour market in the light of the COVID 19 pandemic - quarterly statistics alongside the articles Employment, Absences from work and Hours of work.

Note: this article uses the seasonally adjusted data from the fourth quarter of 2020, i.e. October-December 2020, which is compared in some sections to the fourth quarter of 2019.

Full article

Concept and EU overview

Labour market slack refers to the total sum of all unmet demands for employment and includes four groups: (1) the unemployed people according to the ILO definition, (2) the underemployed part-time workers (i.e. part-time workers who wish to work more), (3) people who are available to work but not searching for it and, (4) people who are searching for work but are not available for it. While the first two groups are in the labour force, the last two, also referred to as the potential additional labour force, are both outside the labour force. For this reason, the “extended labour force”, composed of both the labour force and the potential additional labour force, is used in this analysis. The labour market slack is expressed as a percentage of this extended labour force, and the relative size of each component (each of the four groups) of the labour market slack can be compared by using the extended labour force as a denominator.

<newarticle>In order to better capture the concept and give a first overview at EU level, Figure 1 presents the evolution of the slack and of all its components from Q1 2008 to Q4 2020. In the fourth quarter of 2020, in the EU, the slack accounted for 14.2 % of the extended labour force. Unemployed people stood for a bit less than half of the slack, with 6.9 % of the extended labour force. The remaining part of the slack referred to persons available to work but not seeking it (3.7 %), underemployed part-time workers (2.9 %) and persons seeking work but not immediately available (0.7 %).

(people aged 15-74, in % of the extended labour force)

Source: Eurostat (lfsi_sla_q)

Consecutive decreases in the unmet demand for employment recorded in the third and fourth quarter of 2020 do not outbalance the strong increases recorded in the first and second quarter of 2020

With respect to the developments since the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis, the labour market slack went up from 12.9 % of the extended labour force to 13.4 % (+0.5 percentage points (p.p.)) between the fourth quarter 2019 to the first quarter 2020. This increase was mainly due to the increase in the number of persons available to work but not seeking (+0.4 p.p.) while unemployment remained stable.

Consecutively, from the first to the second quarter of 2020, similar pattern appeared but to a greater extent: the labour market slack reached 15.1%, its record-high in 2020 (+1.7 p.p. compared to the previous quarter) and again, the increase in people available to work but not seeking (+1.5 p.p.) mainly explained the change in the labour market slack. For comparison purpose, unemployment grew by 0.2 p.p., the number of the underemployed part-time workers by 0.1 p.p. and the persons seeking but not available decreased by 0.1 p.p. on the same period. At that time, people who had no job might have reconsidered their job search for a while due to the shutdown or slowdown of many businesses or health measures.

With the partial restart of activity that took place during the third quarter of 2020, the labour market slack decreased very clearly (-0.6 p.p.). In addition, in the slack composition itself, there were also major changes. Indeed, between the second and the third quarter of 2020, people seemed to start again looking for a job: unemployment increased substantially (+0.6 p.p.) and the share of people available to work but not seeking dropped drastically (-1.2 p.p.) while the other components remained roughly stable between both quarters.

From the third to the fourth quarter of 2020, the unmet demand for employment went down by 0.3 p.p. and this decline is mainly due to the decrease in the share of unemployed people (-0.2 p.p.).

Briefly, the decreases in the unmet demand of employment recorded in the third and fourth quarters should be considered as regards the spike reached in the second quarter of 2020. These decreases are far from compensating the significant growths recorded in the first and second quarter of 2020.

For further details, the article on Key consequences of the COVID-19 crisis on the labour market reports on the changes in the slack with respect to employment and people outside the extended labour force. This gives a complete picture of the changes that occurred on the labour market on these aspects and provides a large focus on young people, the most affected by the COVID-19 crisis.

Country comparison in Q4 2020

Shares of people with unmet demand for employment exceeding 20 % of the extended labour force in Spain, Greece and Italy

Among EU Member States, Spain, Greece, and Italy recorded the highest slacks reaching more than one fifth of the extended labour force in the fourth quarter of 2020 (see Figure 2), respectively, 25.1 % in Spain, 23.5 % in Greece and 21.9 % in Italy. Those countries also recorded the biggest gender gaps observed in the slack: 29.6 % for women against 18.4 % for men in Greece (gender gap of 11.2 p.p.), 30.4 % for women against 20.4 % for men in Spain (gap of 10.0 p.p.) and 26.5 % for women against 18.3 % for men in Italy (gap of 8.2 p.p.). The labour market slack of women exceeded the men's slack in all EU Member States except in Estonia and Bulgaria (same shares for men and women) and in Lithuania where the unmet demand for employment of men (12.0 % of the extended labour force) is larger than that of women (11.4% of the extended labour force). Hungary, Malta, Poland and Czechia showed the lowest labour market slacks in the EU with less than 8 % of the extended labour force facing an unmet demand for employment.

(people aged 15-74, in % of the extended labour force)

Source: Eurostat (lfsi_sla_q)

(people aged 15-74, Q4 2020 compared with Q4 2019, in percentage points)

Source: Eurostat (lfsi_sla_q)

Changes with respect to the pre-COVID-19 situation

Higher demand for employment in all EU Member States, except in France, Poland and Greece

The unmet demand for employment in the European Union went up from 12.9 % in the fourth quarter of 2019 which is the reference quarter of the pre-COVID-19 situation, to 14.2 % in the fourth quarter of 2020, indicating the deterioration of the labour market due to the COVID-19 crisis. This decline was also reflected in 24 out of 27 EU Member States.

Referring to Figure 3, the labour market slack also became more substantial between the fourth quarter of 2019 and the fourth quarter of 2020 in all EU countries, apart from France and Poland where it remained stable and Greece where it fell by 0.4 p.p. It also decreased by 0.2 p.p. if only France Metropolitan is considered. In Estonia, Ireland, Austria and Lithuania, the level of unmet demand for employment reached in the fourth quarter of 2020 is still 3 p.p. or more above the level recorded in Q4 2019 respectively, +4.1 p.p. in Estonia, +3.2 p.p. in Ireland and +3.0 p.p. in Austria and Lithuania. By contrast, over the same period, the share of people addressing a potential demand of employment increased but by less than 1 p.p. in Denmark, Italy, Belgium, Luxembourg and Malta.

Men and women reported more disparate developments in Estonia, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Luxembourg and Sweden

In Figure 3, considering the differences between the development in the labour market slack of the men and women, it can be easily seen that in some countries, the slack of men and women did not change to the same extent from Q4 2019 to Q4 2020. In Estonia, women facing an unmet demand for employment increased by 2.7 p.p. from Q4 2019 to Q4 2020 against +5.5p.p for men. In Poland, during the same period, the slack among women decreased by 0.5 p.p. while it increased by 0.5 p.p. for men. By contrast, in Romania, Slovakia, Luxembourg and Sweden, women facing an unmet demand for employment reported larger increases than men: difference of 2.0 p.p. in Romania, 1.2 p.p. in Slovakia, 1.1 p.p. in Luxembourg and 1.0 p.p. in Sweden between the fourth quarter of 2019 and the fourth quarter of 2020.

Slack breakdowns by country

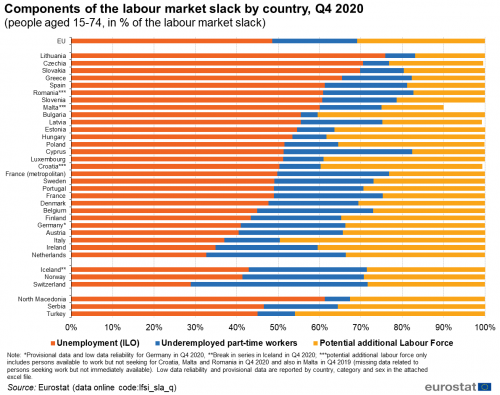

In the fourth quarter of 2020, unemployment accounted for 75.8% of the unmet demand for employment in Lithuania but for less than one third in the Netherlands

(people aged 15-74, in % of the labour market slack)

Source: Eurostat (lfsi_sla_q)

In the fourth quarter of 2020, the structure of the labour market slack was considerably different across EU countries (see Figure 4). In Italy, Ireland and the Netherlands, unemployment stood at less than 40 % of the total national slack, while the underemployed part-time workers and people in the additional labour force accounted together for more than 60 % of the slack. This means that in those countries, these two categories supplement substantially the unemployment if the whole unmet demand for employment is considered. In contrast, unemployment accounted for more than 70 % of the total labour market slack in Lithuania and Czechia while the other categories are less prominent than in the other countries.

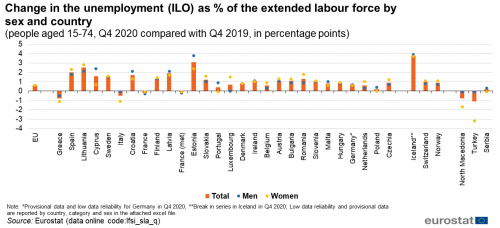

Focus on unemployment

Unemployment (ILO) is one component of the labour market slack. In the EU, it stood at 6.9 % of the extended labour force in the fourth quarter of 2020, specifically reaching 7.1 % for women and 6.7 % for men (see Figure 5).

In Greece and Spain, more than one in seven persons in the extended labour force was unemployed in the fourth quarter of 2020 (15.4 % in both countries). Moreover, Greece and Spain are among the countries for which the widest gap between men and women was found in the unemployment rate as it was also observed for the whole slack. In Greece, female unemployment accounted for 18.4 % and male unemployment for 12.9 % (difference of 5.5 p.p.). In Spain, unemployment stood at 17.2 % for women against 13.8 % for men (difference of 3.4 p.p.). Moreover, in the fourth quarter of 2020, the share of unemployed women in the extended labour force exceeded by 1.0 p.p. or more the share of unemployed men in Luxembourg and Czechia and reciprocally, the male unemployment rate exceeded the female unemployment rate by 1.0 p.p. or more in Lithuania, Germany and Latvia. In contrast, four EU Member States registered an unemployment rate of less than 4.0 % of the extended labour force: Czechia (2.9 %), Poland (3.1 %), Germany and the Netherlands (3.8 % each).

(people aged 15-74, in % of the extended labour force)

Source: Eurostat (lfsi_sla_q)

(people aged 15-74, Q4 2020 compared with Q4 2019, in percentage points)

Source: Eurostat (lfsi_sla_q)

In the fourth quarter of 2020, the unemployment rate was higher than in Q4 2019 in the whole EU and in the vast majority of EU Member States (24 out 27 exactly). At EU level, it increased by 0.6 p.p. (6.9 % in Q4 2020 against 6.3 % in Q4 2019), see the dynamic tool choosing unemployment (ILO) and Figure 6. However, in 14 EU countries, the unemployment rate was 1.0 p.p. or more larger in Q4 2020 comparing the two quarters. Estonia, Lithuania and Spain recorded the most substantial increases compared to the last quarter of 2019 (+3.1 p.p., +2.5 p.p. and +2.0 p.p.). In contrast, the share of unemployed people in the extended labour force decreased in France (-0.1 p.p. in France metropolitan and -0.2 p.p.in France), in Italy (-0.5 p.p.) and in Greece (-0.8 p.p.). It may be useful to remember in this specific section on unemployment that in order to be considered unemployed according to the ILO's criteria, a person should be without work during the reference week, available to start working within the next two weeks (or has already found a job to start within the next three months) and have actively sought employment at some time during the last four weeks. As aforementioned, this indicator should be carefully considered when taken to report on the COVID-19 crisis. The health measures might affect the job search status of people i.e. people start or stop looking for a job depending on the level of activity in their country or might affect their availability to work (e.g. people might be available or not depending on the school opening).

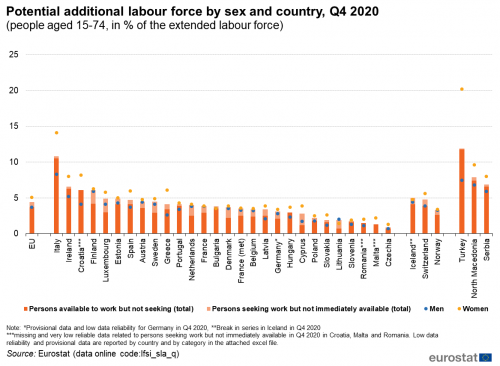

Focus on the potential additional labour force

Larger potential additional labour force in the fourth quarter of 2020 than in Q4 2019 in 23 out of 27 EU Member States

As already mentioned, the potential additional labour force consists of two subgroups which are both outside the labour force, due to people's unavailability to work or lack of job search, but inside the extended labour force. One of these subgroups includes people who are available to work but do not seek it. At EU level, in the fourth quarter of 2020, this category accounted for 3.7 % of the extended labour force (see Figure 7). The other subgroup is related to persons who seek work but are not immediately available to start working; this last group stood at 0.7 %. In total, 4.4 % of the extended labour force are actually not employed or even unemployed but connected to employment by expressing a certain willingness or demand for work. All countries, apart from Lithuania and Cyprus, follow the same main pattern clearly visible in Figure 7: people available to work but not seeking outnumber those seeking work but not immediately available. Gender differences can be found at EU level. Indeed, the female potential additional labour force, as a percentage of the female extended labour force, stood at 5.1 %, and the male potential additional labour force, as a percentage of the male extended labour force, at 3.7 % in the fourth quarter of 2020. Largest share of potential additional labour force are found in Italy with 10.8 % of the extended labour force, Ireland (6.6%), Finland (6.1%) and Croatia (6.1% but for Croatia, it only refers to people available but not looking for a job). In Czechia, the potential additional labour force amounted to 0.9% of the extended labour force, that was the lowest share recorded.

(people aged 15-74, in % of the extended labour force)

Source: Eurostat (lfsi_sla_q)

(aged 15-74, Q4 2020 compared with Q4 2019, in percentage points)

Source: Eurostat (lfsi_sla_q)

In three out of the 24 EU Member States for which data is available for both categories of the potential additional labour force, in the fourth quarter of 2020, the share of the potential additional labour force exceeded the share of unemployed people in the extended labour force: in Italy (+2.7 p.p. compared to unemployment), Ireland (+0.9 p.p.) and the Netherlands (+0.2 p.p.).

Figure 8 shows the comparison of the potential additional labour force between the fourth quarter of 2019 and the fourth quarter of 2020. In the vast majority of the EU countries for which data is available, the share increased. The highest growths in Ireland, Greece, Germany and Austria where it went up by more than 1p.p. At the same time, it amounted to the same level of Q4 2019 in Finland and Poland and slightly decreased in Belgium (-0.1 p.p.) and Latvia (-0.2 p.p.).

Note: due to low data reliability related to the category "people who are seeking but not immediately available", only persons available to work but not seeking are included in Figure 7 and 8 for Croatia, Malta and Romania.

Focus on underemployed part-time workers

Almost 3% of the extended labour force consisted of part-time workers who want to work more hours in the EU, but around 5% in Spain and Cyprus.

Among the extended labour force, the highest shares of part-time workers wanting to work more were found in the fourth quarter of 2020 in Spain (5.0 %), Cyprus (4.9 %), France (both France and France Metropolitan (4.1 %)), Ireland, Greece, the Netherlands and Sweden (all four with 4.0 %) (see Figure 9). In contrast, less than 0.5 % of the extended labour force in Czechia and Bulgaria were underemployed part-time workers (0.3 % and 0.4 % respectively) making them a relatively small group within the extended labour force (see Figure 9).

At EU level, 2.9 % of the extended labour force were underemployed part-time workers. This share reached 4.1 % for women more than the double than the share of men (1.9 %).

(people aged 15-74, in % of the extended labour force)

Source: Eurostat (lfsi_sla_q)

(people aged 15-74, Q4 2020 compared with Q4 2019, in percentage points)

Source: Eurostat (lfsi_sla_q)

Comparing the fourth quarter of 2020 to the fourth quarter of 2019, the share of underemployed part-time workers, as a percentage of the extended labour force, remained relatively stable (+0.1 p.p. at EU level) (see Figure 10). However, five countries recorded an increase exceeding +0.5 p.p. between both quarters: Netherlands and Sweden (+0.7 p.p.), Austria (+0.6 ), Italy and Estonia (+0.5 ). Lower shares of underemployed part-time workers in Q4 2020 compared with Q4 2019, with differences bigger than of 0.3 p.p. were found in Greece (-0.8 p.p.) and Ireland (-0.4 p.p.).

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

All figures in this article are based on seasonally adjusted quarterly results from the European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS).

Source: The European Union labour force survey (EU-LFS) is the largest European household sample survey providing quarterly and annual results on labour participation of people aged 15 and over as well as on persons outside the labour force. It covers residents in private households. Conscripts in military or community service are not included in the results. The EU-LFS is based on the same target populations and uses the same definitions in all countries, which means that the results are comparable between countries.

European aggregates: EU refers to the sum of EU-27 Member States.

Country note: In Germany, from the first quarter of 2020 onwards, the Labour Force Survey (LFS) is part of a new system of integrated household surveys. Unfortunately, technical issues and the COVID-19 crisis has had a large impact on data collection processes, resulting in low response rates and a biased sample. For this reason, additional data from other integrated household surveys has been used in addition to the LFS subsample, to estimate a restricted set of indicators for the first three quarters of 2020, for the production of LFS Main Indicators. These estimates have been used for the publication of German results, but also in the calculation of EU and EA aggregates. By contrast, EU and EA aggregates published in the Detailed quarterly results (showing more and different breakdowns than the LFS Main Indicators) have been computed using only available data from the LFS subsample. As a consequence, small differences in the EU and EA aggregates in tables from both collections may be observed. For more information, see here.

Definitions: The concepts and definitions used in the Labour Force Survey follow the guidelines of the International Labour Organisation.

Five different articles on detailed technical and methodological information are linked from the overview page of the online publication EU Labour Force Survey.

Context

The COVID-19 pandemic hit Europe in January and February 2020, with the first cases confirmed in Spain, France and Italy. COVID-19 infections have now been diagnosed in all European Union (EU) Member States. To fight the pandemic, EU Member States have taken a wide variety of measures. From the second week of March, most countries closed retail shops apart from supermarkets, pharmacies and banks. Bars, restaurants and hotels have also been closed. In Italy and Spain, non-essential production was stopped and several countries imposed regional or even national lock-down measures which further stifled the economic activities in many areas. In addition, schools were closed, public events were cancelled and private gatherings (with numbers of persons varying from 2 to 50) were banned in most Member States.

The large majority of the prevention measures were taken during mid-March 2020 and most of the prevention measures and restrictions were kept for the whole of April and May 2020. The first quarter of 2020 is consequently the first quarter in which the labour market across the EU has been affected by COVID-19 measures taken by the Member States.

Employment and unemployment as defined by the ILO concept are, in this particular situation, not sufficient to describe the developments taking place in the labour market. In this first phase of the crisis, active measures to contain employment losses led to absences from work rather than dismissals, and individuals could not search for work or were not available due to the containment measures, thus not counting as unemployed.

The three indicators supplementing the unemployment rate presented in this article provide an enhanced and richer picture than the traditional labour status framework, which classifies people as employed, unemployed or outside the labour force, i.e. in only three categories. The indicators create ‘halos’ around unemployment. This concept is further analysed in a Statistics in Focus publication titled 'New measures of labour market attachment', which also explains the rationale of the indicators and provides additional insight as to how they should be interpreted. The supplementary indicators neither alter nor put in question the unemployment statistics standards used by Eurostat. Eurostat publishes unemployment statistics according to the ILO definition, the same definition as used by statistical offices all around the world. Eurostat continues publishing unemployment statistics using the ILO definition and they remain the benchmark and headline indicators.

Direct access to

- New measures of labour market attachment - Statistics in focus 57/2011

- European Union Labour force survey - selection of articles (Statistics Explained)

- LFS main indicators (lfsi)

- Unemployment - LFS adjusted series (une)

- Supplementary indicators to unemployment - annual data (lfsi_sup_a)

- Supplementary indicators to unemployment - quarterly data (lfsi_sup_q)

- Unemployment - LFS adjusted series (une)

- LFS series - Detailed annual survey results (lfsa)

- Total unemployment - LFS series (lfsa_unemp)

- Supplementary indicators to unemployment by sex and age (lfsa_sup_age)

- Supplementary indicators to unemployment by sex and educational attainment level (lfsa_sup_edu)

- Supplementary indicators to unemployment by sex and citizenship (lfsa_sup_nat)

- Total unemployment - LFS series (lfsa_unemp)

- LFS series - Detailed quarterly survey results (lfsq)

- Total unemployment - LFS series (lfsq_unemp)

- Supplementary indicators to unemployment by sex and age (lfsq_sup_age)

- Supplementary indicators to unemployment by sex and educational attainment level (lfsq_sup_edu)

- Total unemployment - LFS series (lfsq_unemp)