Archive:Europe 2020 indicators - employment

Data extracted in August 2019.

No planned update.

Highlights

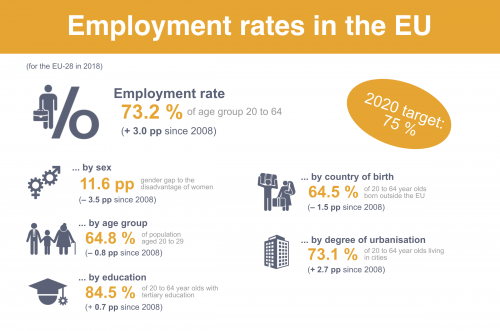

In 2018 the overall employment rate in the EU reached 73.2 %. If the employment rate keeps increasing at the pace recorded since 2013, the Europe 2020 target would be within reached.

(%)

Source: Eurostat online data code (t2020_10)

This article is part of a set of statistical articles on the Europe 2020 strategy. It provides recent statistics on employment and other labour market-related issues in the European Union (EU).

Full article

General overview

The Europe 2020 strategy is the EU’s agenda for growth and jobs for the current decade. It emphasises smart, sustainable and inclusive growth as a way of strengthening the EU economy and making it resilient towards forthcoming challenges.

Employment is a key policy component of the Europe 2020 strategy. Decent employment for all is crucial for ensuring adequate living standards. On top of contributing to quality of life and social inclusion of individuals, it also improves the well-being of the society as a whole, which makes it one of the cornerstones of socioeconomic development.

Overall, the EU labour market has consistently shown positive dynamics, with substantial progress towards the Europe 2020 strategy employment rate target. At the same time, long-term changes in the demographic structure of the EU population and rapid technological change add to the need to reform labour markets. Taking into account the decline in the working-age population (aged 20 to 64) accompanied by a rising old-age dependency ratio, higher employment rates, especially for women, older workers and young people remain among the priorities of the Europe 2020 strategy.

Europe 2020 strategy target on employment

The Europe 2020 strategy sets out a target of ‘increasing the employment rate of the population aged 20 to 64 to at least 75 %' by 2020 [1].

EU employment on the rise again — signs of gradual recovery

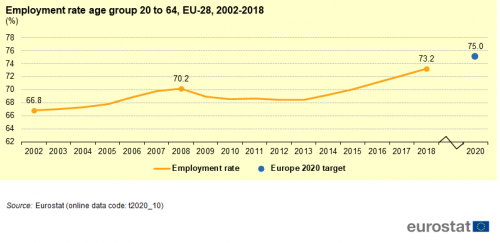

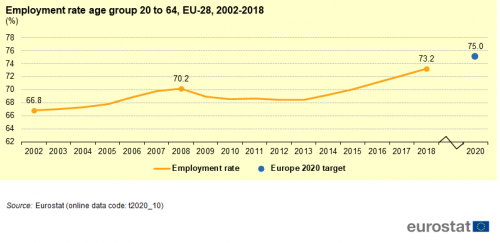

In 2017 and 2018, the EU labour market continued to show marked signs of improvement, benefiting from economic growth, a strong global outlook and favourable macroeconomic policies [2]. Overall, the EU employment rate has shown an upward trend in recent years (with some interruptions in the aftermath of the economic crisis), growing by 6.4 percentage points since 2002 and reaching a record high of 73.2 % in 2018.

The Europe 2020 strategy monitors its employment target through the headline indicator ‘Employment rate — age group 20 to 64’, which shows the share of employed 20- to 64-year-olds in the total EU population [3]. In 2018, 220 million people (73.2 % of the EU population) were employed [4] — 2.3 million (or 1.0 percentage points) more than in 2017. As Figure 1 shows, there is still a 1.8 percentage point gap that needs to be closed to reach the Europe 2020 employment target of 75 % by 2020. However, the EU is well placed to reach this target if the growth rate recorded since 2013 continues.

(%)

Source: Eurostat online data code (t2020_10)

North–south divide in employment rates across the EU

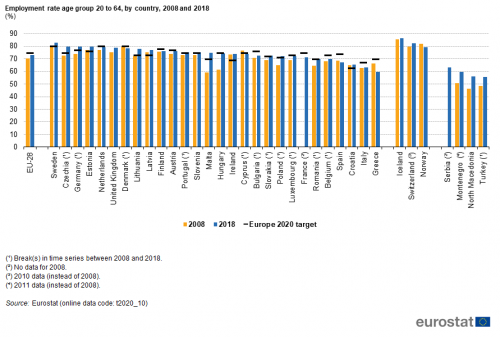

In 2018, employment rates among Member States ranged from 59.5 % in Greece to 82.6 % in Sweden (see Figure 2). Northern and central European countries recorded the highest rates; half of the EU Member States even exceeded the 75 % EU employment target. With employment rates below 70 %, Mediterranean countries, along with Romania and Belgium, represented the lower end of the distribution. Employment rates in the EFTA countries Iceland, Switzerland and Norway were higher than in the majority of Member States.

Between 2008 and 2018, employment rates rose in most EU countries, with the strongest growth recorded in Malta (15.8 percentage points) and Hungary (12.9 percentage points). In four Member States (Greece, Cyprus, Spain and Denmark) employment rates were still below 2008 levels, however, all of these countries were back on a ‘growth path’ by 2018.

To reflect different national circumstances, the general EU target has been translated into national targets. These range from 62.9 % for Croatia to 80.0 % for Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden. In 2018, 13 Member States had already met their national employment targets. Of the remaining Member States, eight were less than 2 percentage points below their national targets, led by Romania which was just 0.1 percentage points from its target. Greece and Spain were the most distant, at 10.5 and 7.0 percentage points below their national targets, respectively.

In a global context, compared with non-EU G20 economies, the employment rate of the EU — here referring to the age group 15 to 64 — was higher than in two-thirds of these countries in 2018. Japan, Canada, Australia, the US and Russia showed higher rates of above 70 %. In contrast, India, Saudi Arabia and South Africa reported particularly low employment rates of 52.0 %, 51.7 % and 43.3 %, respectively.

(%)

Source: Eurostat online data code (t2020_10)

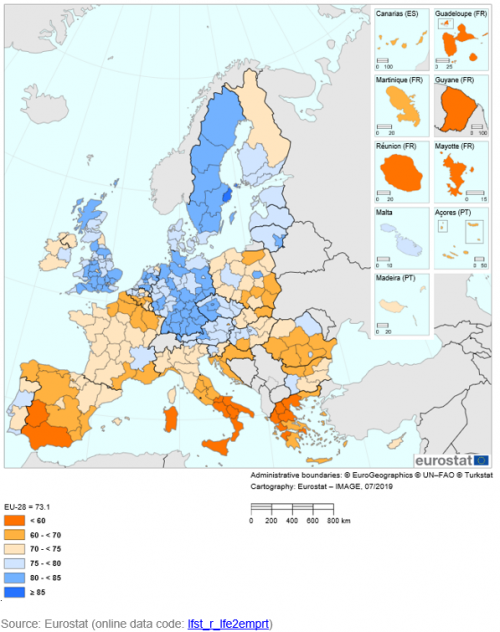

Highest employment rates recorded in regions in north-western and central Europe

Differences in employment rates across Member States, shown in Figure 2, are also reflected in the cross-country regional distribution of employment rates (at NUTS 2 level). Map 1 shows that Europe’s highest employment rates were mainly recorded in north-western and central regions, particularly in Germany, Sweden, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Austria and Czechia. In 2018, the Swedish region of Stockholm had the highest employment rate in the EU, at 85.7 %, followed by Åland (Finland), at 85.1 %, and Oberbayern (Germany), at 84.1 %. At the other end of the scale, the lowest rates were observed around the Mediterranean, in particular in southern Italy, Spain and Greece, as well as in the French overseas regions and the outlying Spanish autonomous cities (Ceuta and Melilla). In 2018, the French region Mayotte and the Italian regions Sicilia, Campania, Calabria and Puglia had the lowest employment rates in the EU, with less than 50 %.

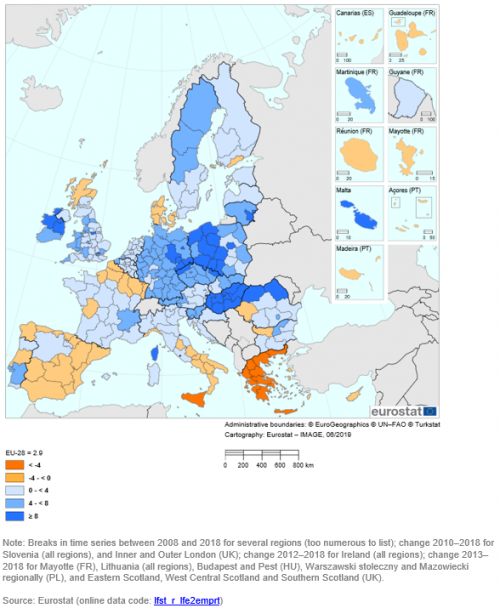

Map 2 shows the change in regional employment rates since 2008. Among the 281 NUTS 2 regions for which data are available, 22 % (62 regions) experienced a fall in their employment rates over the period observed. Among the hardest hit were several regions in Greece, with reductions of six percentage points or more. In contrast, employment rates increased in 216 regions from 2008 to 2018. Growth rates of 10 percentage points or more were observed in 18 of these regions, seven of which were in Hungary, three in Poland, two in Romania, Germany and Ireland and one in Malta and France. Increases of more than 15 percentage points were recorded for regions in Hungary (Észak-Alföld, Észak-Magyarország, Dél-Alföld) and in Malta.

(%)

Source: Eurostat online data code (lfst_r_lfe2emprt)

(percentage points difference, 2018 minus 2008)

Source: Eurostat online data code (lfst_r_lfe2emprt)

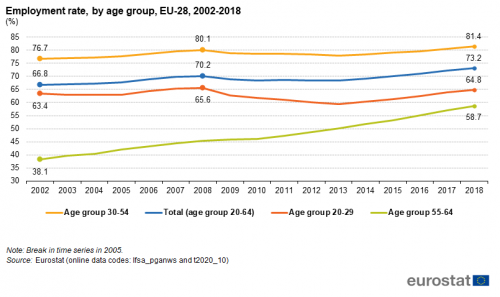

Younger and older people tend to have lower employment rates

In 2018, the employment rate of people aged 30 to 54 was notably higher than for the overall working-age population aged 20 to 64 (see Figure 3). In contrast, considerably lower employment rates were observed for young people aged 20 to 29. This may not only reflect the overall lower activity rates [5] of younger people but may also be due to the generally less secure position of young people in the labour market, which makes youth employment more sensitive to the macro-economic fluctuations than adult employment.

The lowest employment rate among the working-age population was reported for the group aged 55 to 64 years. However, the employment rate in this group has risen continuously since 2002, reaching 58.7 % in 2018. Growth has been slightly more pronounced for older women (23.6 percentage points) than for older men (17.3 percentage points) since 2002. Overall, the increase in the employment rate of older workers is one of the main drivers of the total rise in employment across the EU. These increases can be linked to structural factors such as cohorts with better educational attainment, especially women, moving up the age pyramid as well as recent pension reforms, such as increases in the pensionable age, the age for early retirement and the length of pension contribution [6]. This has led to longer working lives for both women and men.

(%)

Source: Eurostat online data codes (lfsa_pganws)and (t2020_10)

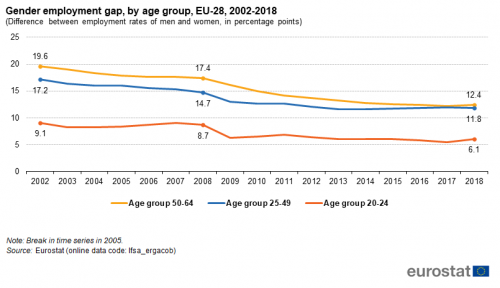

Women still have lower employment rates but the gender employment gap is shrinking

Despite women becoming increasingly well qualified and even out-performing men in terms of educational attainment, the activity and employment rates of women remain lower than those for men. However, as shown in Figure 4, the gender employment gap — the difference in employment rates between men and women — has been decreasing for all age groups. Overall, for the age group 20 to 64, the gap narrowed from 17.3 percentage points in 2002 to 11.5 percentage points in 2018. A number of structural factors influencing the participation of women in the labour market may account for why they have been catching up with men. These include changes in social values and attitudes, policies enabling women to reconcile paid work with household responsibilities such as child care provision, flexible working hours, reduction in financial disincentives for women, improved mechanisms to encourage fathers' parental engagement and pension reforms [7]. European employment policies promoting new forms of flexibility and security are addressing the specific situation of women to help raise their employment rates in line with the headline target.

In 2018, the gender employment gap for 25 to 49 year olds was at 11.8 percentage points, which is 5.4 percentage points less than in 2002. The bigger gap for this age group in comparison to the 20 to 24 age group is not surprising as women in this group are more likely to be economically inactive than men [8] due to caring responsibilities for children. In 2018, family and caring responsibilities were the main reason for inactivity among 52.5 % of women aged 25 to 49 compared with 7.9 % of men [9].

In addition to caring responsibilities, women can face strong financial disincentives in tax-benefit systems when re-entering the labour market or wanting to work more [10]. Time out of the labour force for these reasons might also affect employment opportunities in later years because finding a job becomes more difficult the longer a person is not employed. This might partially explain why the gender employment gap was smaller for 20 to 24 years old, at 6.1 percentage points, in 2018. Higher gender gaps in (short-term) employment rates in older age cohorts may be explained by a cohort effect (women who did not participate in the labour force when they were younger have moved up the age pyramid) or reflect the lack of care facilities for grandchildren or dependent parents.

(Difference between employment rates of men and women, in percentage points)

Source: Eurostat online data code (lfsa_ergacob)

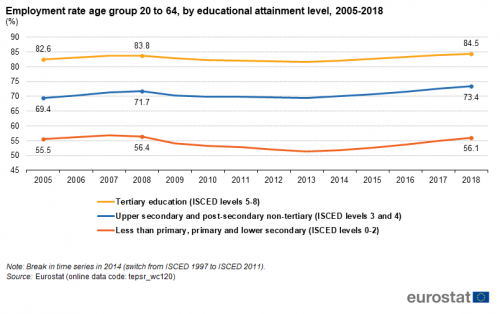

Higher education levels increase employability

Educational attainment level is the main factor that influences employment rates. Employment rates are higher for people having at least upper-secondary education (see Figure 5). In 2018, the employment rate among tertiary education graduates (84.5 %) was much higher than the EU average total (73.2 %). In contrast, just slightly more than half of those with at least primary or lower secondary education were employed. The employment rate for people with upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education was in between these levels and slightly above the overall EU average employment rate.

These findings underline the importance of education for employability. European employment policies reflect this necessity by addressing Europe 2020 headline targets on employment and education (see ‘Education’ article).

(%)

Source: Eurostat online data code (tepsr_wc120)

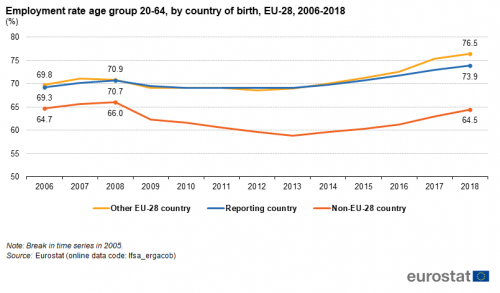

Employment rates among non-EU migrants are considerably low

Economic migration is becoming increasingly important for the EU’s ability to deal with a shrinking labour force and expected skills’ shortages. According to current projections population projections, without net migration the working-age population aged 20 to 64 would shrink by 7.4 % by 2030 and by 28.1 % by 2060 compared with 2018 levels. Moreover, the working-age population is expected to decline even with net migration into the EU, but at slower rates of – 3.8 % by 2030 and – 12.5 % by 2060 [11].

However, country of birth can affect a person’s labour market performance. Migrant workers from countries outside the EU tend to occupy low-skilled and insecure jobs with temporary contracts and poorer working conditions [12]. Migrants are also among the first to lose their jobs during economic setbacks. Much lower employment rates are consequently reported for this group than for EU-born workers (see Figure 6). In 2018, the employment rate of people born outside the EU aged 20 to 64 was 8.7 percentage points below the total employment rate. Additionally, their employment rate has so far not recovered from the setback caused by the economic crisis, with the 2018 rate being still lower than the levels recorded in 2008.

(%)

Source: Eurostat online data code (lfsa_ergacob)

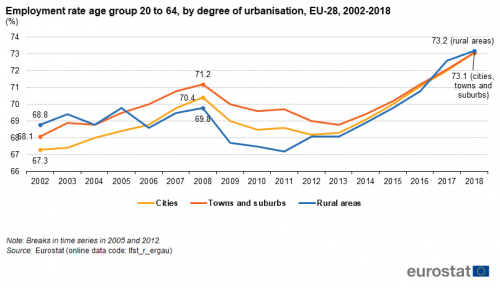

Employment rates in cities, towns and suburbs, and rural areas have converged at EU level

There was almost no difference in the employment rates by degree of urbanisation at the EU level in 2018. Cities, towns and suburbs have recorded an employment rate of 73.1 % and rural areas of 73.2 %. However, this difference was discernible at country level. In many European countries (such as Belgium, Austria, Germany and Greece), employment rates tended to be higher in rural areas. In contrast, more than half of the Member States exhibited higher employment rates in cities in 2018, with Bulgaria, Lithuania and Croatia showing the biggest gap.

(%)

Source: Eurostat online data codes (lfst_r_ergau)

Data sources

Indicators presented in the article:

- Employment rate age group 20-64 (t2020_10)

- Breakdown by country (t2020_10)

- Breakdown by NUTS 2 regions (lfst_r_lfe2emprt)

- Breakdown by degree of urbanisation (lfst_r_ergau)

- Breakdown by age groups (lfsa_pganws, t2020_10)

- Breakdown by educational attainment level (tepsr_wc120)

- Breakdown by country of birth (lfsa_ergacob)

- Gender employment gap (lfsa_ergacob)

Context

Employment and other labour market-related issues are at the heart of the social and political debate in the EU. Paid employment is crucial for ensuring adequate living standards and it provides the necessary base for people to achieve their personal goals and aspirations. Moreover, employment’s contribution to economic performance, quality of life and social inclusion makes it one of the cornerstones of socioeconomic development and well-being.

Demographic changes over the past few decades have led to a greater share of older people than younger people in the population. Because of these changes, a smaller number of workers are now supporting a growing number of dependent people. Thus, putting the sustainability of Europe’s social model, welfare systems, economic growth and public finances at risk. At the same time, global challenges are intensifying and competition from developed and emerging economies such as China and India is increasing [13].

To face the challenges of an ageing population and rising global competition, the EU needs to make full use of its labour potential. The Europe 2020 strategy, through its ‘inclusive growth’ priority, places a strong emphasis on job creation. One of its five headline targets addresses employment, with the aim of raising the employment rate of 20- to 64-year-olds to 75 % by 2020.

The EU’s employment target is closely interlinked with the strategy’s other goals on research and development (R&D) (see the article on 'R&D and innovation'), education (see the article on 'Education') and poverty and social exclusion (see the article on ‘Poverty and social exclusion’). Higher educational levels increase employability and higher employment rates can in turn contribute to improved economic performance and poverty reduction, thus addressing the strategy’s inclusive growth objective [14]. Moreover, boosting R&D capacity and innovation could improve competitiveness and thus contribute to job creation.

Overall, the EU labour market has consistently shown positive dynamics, with substantial progress towards the Europe 2020 strategy’s employment rate target. At the same time, long-term changes in the EU population’s demographic structure and rapid technological change add to the need for labour market reform. Taking into account the decline in the working-age population and a rising old-age dependency ratio, it is important that higher employment rates, especially among women, and young and elderly people, remain among the Europe 2020 strategy’s priorities.

Direct access to

<seealso>

<seealso>

- Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council COM(2011) 211 final Towards robust quality management for European Statistics

<legislation>

- Regulation (EC) No 223/2009 of 11 March 2009 on European statistics

- Summaries of EU Legislation: European statistics: how the European Statistical System works

<legislation>

Notes

- ↑ European Commission (2014), Taking stock of the Europe 2020 strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, COM(2014) 130 final, Brussels.

- ↑ European Commission (2018), Labour Market and Wage Developments in Europe — Annual review 2018, Publication Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

- ↑ The age brackets for this headline indicator are narrower than for Eurostat descriptive statistics based on the Labour Force Survey, where employment covers people aged 15 years and older. In this report, people below the age of 20 are excluded because many of them are still in education or training and are not actively seeking employment (only 20.4 % of this age group were part of the labour force in 2018, see Eurostat online data code (lfsa_pganws)). The upper age limit is set to 64 years to take account of statutory retirement ages across Europe.

- ↑ According to the definitions of the International Labour Organization (ILO), persons in employment are those who, during the reference week, did any work for pay or profit, or were not working but had a job from which they were temporarily absent.

- ↑ The activity rate is the share of the population that is economically active. The economically active population is the sum of employed and unemployed persons.

- ↑ European Commission (2017), Employment and Social Developments in Europe — Annual review 2017, Publication Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, p. 34.

- ↑ European Commission (2016), Employment and Social Developments in Europe — Annual review 2015, Publication Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, p. 22.

- ↑ Economically inactive persons are those who, during the reference week, were neither employed nor unemployed. People are considered unemployed if they were 1) without work during the reference week; 2) available to start work; and 3) actively seeking work.

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (lfsa_igar))

- ↑ European Commission (2017), Women in the labour market, European Semester Thematic Factsheet 2017, p. 4.

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (proj_18np)).

- ↑ European Commission (2017), Employment and Social Developments in Europe — Annual review 2017, Publication Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, p. 83.

- ↑ European Commission (2010), Europe 2020 — A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, COM(2010) 2020 final, Brussels, p. 5, 7, 17.

- ↑ Inclusive growth means empowering people through high levels of employment, investing in skills, fighting poverty and modernising labour markets, training and social protection systems so as to help people anticipate and manage change, and build a cohesive society. See: European Commission (2010), Europe 2020 — A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, COM(2010) 2020 final, Brussels, p. 17.