Archive:Material deprivation statistics – financial stress and lack of durables

- Data extracted in July 2016.

This article is part of the Eurostat online publication Living conditions providing statistics on material deprivation in the European Union (EU) with focus on intra-household sharing of the resources for 2014. The publication presents a brief analysis of several different material deprivation variables (as part of the 2014 EU-SILC ad-hoc module) which relate to the household (as a whole), adults (people aged[1] 16 and over) and children (all household members aged between 1 and 15). Observed variables, among others, are related to financial stress and durables, and leisure and social activities as a broader perspective of social inclusion measurements.

Even though it is tempting to assume that a change in a household’s income will affect all its members to the same extent, reality could differ dramatically. Using only household level indicators and attribute them equally to each member of the household, could possibly lead to unobserved child poverty and child deprivation as well as of the other age- and gender-groups within the same household. In order to shed some light on the intra-household transfers and within-household differences in living conditions, the EU-SILC included a special ad-hoc material deprivation module (first time for 2009, and revised for 2014) which allows to observe this separately for different demographics.

The variables related to children’s items are collected for the whole group of children[2] with one very specific rule: If at least one child does not have the item in question, the whole group of children in the household is assumed to not have the item either. On the other hand, information on basic needs, as well as leisure and social activities for adults is provided for each household member aged 16 and over.

Analyses used for the article cover all EU Member States and several non-EU Member States.

(% of adults)

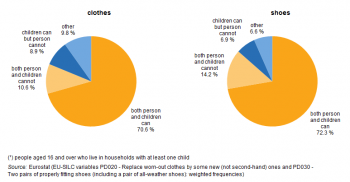

Source: Eurostat (EU-SILC variables PD020 - Replace worn-out clothes by some new (not second-hand) ones and PD030 - Two pairs of properly fitting shoes (including a pair of all-weather shoes): weighted frequencies)

Main statistical findings

Child deprivation

In 2014, 27.4% of children aged below 16 in the EU-28 were at risk of poverty or social exclusion (AROPE[3] ) compared with 25.5% of adults aged between 16 and 64, and 17.7% of the elderly (aged 65 or over).

The main EU-SILC indicators (Europe 2020 target on poverty and social exclusion) measure living conditions using general indicators of the household as a whole and they are based on the assumption that the recourses are equally distributed to all household members. The aim of this part is to show if the situation changes when we observe some of the material deprivation variables separately for specific child groups (children aged 1-15).

This part of the article focuses on several material deprivation items – meal and lack of space, and on the household’s (in)ability to afford them for all children and (or) for all its members.

As mentioned at the beginning, due to specific characteristics of the collected information (i.e. the number of variables and breakdown details) and missing values, some households (and their members) are excluded from the analysis.

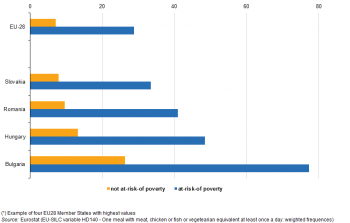

Food-deprivation

In 2014, based on the EU-SILC survey, 13.2% of children were living in households which could not afford a meal for all children every day.

The context of food-deprivation in this article is focused on households which could not afford one meal with meat, chicken or fish (or vegetarian equivalent)[4] for all children at least once a day.

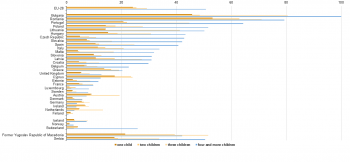

Figure 1.1 shows the proportions of children who lived in households which could not afford a meal for all children at least once a day by monetary poverty. As assumed, proportions of children who lived in households which were at risk of poverty were much higher when compared with the ones who are not (at EU28 level – 7.1% in households not at risk of poverty and 28.8% in households at risk of poverty).

The highest proportions of children, among EU-28, who lived in households which were at risk of poverty and which could not afford one meal per a day for all children, were recorded in Bulgaria (77.2%), Hungary (48.5%) and Romania (40.9%).

Among children who lived in households which are not at risk of poverty, more than 26% of them lived in Bulgaria in households which could not afford at least one meal per day for all children. In 2014, based on the EU-SILC survey, 14.9% of children in EU lived in households which could not afford a meal for all its members at least every second day. In comparison, 13.2% of children lived in households which could not afford a meal for all children every day.

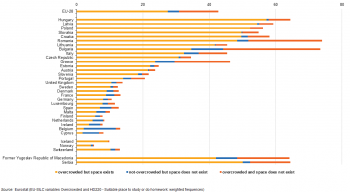

Lack of space

In 2014, 40.7% of children in the EU lived in overcrowded[5] households . Also, 14.1% of children lived in households which could not afford a suitable place for them to study or do homework.

In Romania and Hungary, over 80% (81.8% and 81.4% respectively) of children lived in overcrowded households which were also at risk of poverty. Moreover, in Romania, around 64.3% of children lived in overcrowded households which were not at risk of poverty. The lowest proportion of children (below 5%) who lived in overcrowded households was in Belgium (2.7%), Cyprus (2.9%), Ireland and Norway (4.1% both).

Among the EU-28, Bulgaria was the country with the highest percentage (64.0%) of children who lived in households at risk of poverty and did not have space[6] to study due to financial reasons. On the contrary, Finland had the lowest share of children who lived in households with the aforementioned characteristics – only 3.4%.

Even though there is an evident difference in whether a household is at risk of poverty or not, for some countries, proportions of children who lived in households which were not at risk of poverty but who still could not afford a space for school-age children, were relatively high – Bulgaria (28.1%), Romania (18.0%) and Spain (17.4%). However, for majority of EU and non-EU Member States, this share of children was less than 4%. Since the shares of children who lived in overcrowded households for most EU-28 countries were relatively high (at EU28 level - 36.5% in households not at risk of poverty and 54.6% in households at risk of poverty), the aim of the next part of the article is to see if the lack of space for studying and doing homework for school-aged children is linked to a lack of space.

The majority of people lived in households which were not overcrowded and where the suitable space existed. However (see Figure 1.2), in Belgium and Bulgaria almost 10% of households were not overcrowded but still did not have space to study for children. Furthermore, in Hungary, Latvia and Poland, over 50% of people lived in overcrowded households but with enough space for school-aged children to study or do their homework (57.3%, 54.4% and 52.2% respectively).

Inter- and intra-generational differences

One of the main EU-SILC indicators – AROPE, showed that young persons (under 25) present the most vulnerable group. More precisely, the percentage of people who lived in severe material deprivation and in households at risk of poverty (AROPE) was slowly decreasing with age – from 31.9% for age group 18-24 to 17.8% for people aged 65 and over.

The aim of this part of the article is to apply a broader perspective of material deprivation, i.e. inability to afford a selection of items (goods or services) and if this pattern still exists if we observe them at personal level. To adequate measure children’s material deprivation it is necessary to look not only at the material deprivation that solely affects children but also at the material deprivation that affects the entire household as this is likely to impact their living conditions.

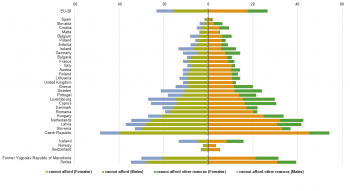

New clothes and two pairs of shoes

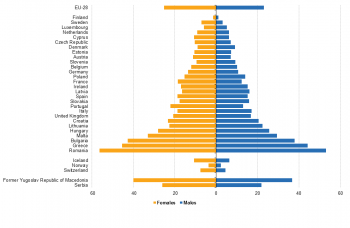

In 2014, 16.7% of people in the EU aged 16 and over could not afford to replace worn-out clothes by some new (not second-hand) ones and 18.9% of people of the same age could not afford two pairs of properly fitting shoes (including a pair of all-weather shoes).

Figure 2.1 shows percentages of people aged 16 and over by their ability to afford new clothes by gender. Observing totals, Bulgaria (42.4%), Romania (31.6%) and Hungary (29.6%) were the EU28 countries with the highest proportion of people who could not afford to replace worn-out clothes with new. The share was less than 3% in Greece (1.3%) and Sweden (2.2%).

Even though in some countries the percentages of people who could not afford new clothes were high, in Italy, Croatia and Slovakia percentages of people who could not replace clothes for other reasons was over 10% (13.4%, 12.9% and 11.5% respectively).

Observing person`s ability to afford new clothes by gender, among the EU-28, in almost all cases women were more vulnerable than men regardless the reasons (financial or non-financial). More precisely, at EU28 level – 17.6% women and 15.7% of men were not able to afford new clothes. Only in Spain and Ireland, the percentage of men was higher than percentage of women but that difference is not significant.

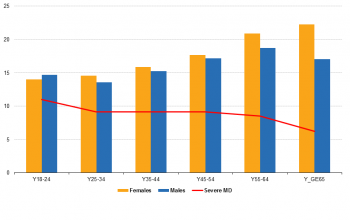

Figure 2.2 shows both intra-generational and gender differences observing inability of each person in the EU (aged over 17) to afford new cloths vs. severe material deprivation rate as a broader perspective of material deprivation measurements by gender and main age-groups.

When observing the severe material deprivation rate at household level, the age group 18-24 was the most vulnerable, while the age group 65 and over had the lowest rate. Yet the largest proportion of persons aged 18 and over could afford new clothes. People aged 65 and over were more vulnerable than the age group 18-24 and had the lowest proportion of those who could afford to replace worn out clothes with new ones.

When it comes to gender differences, for all age groups except for people aged 18-24, women were more vulnerable than men. The proportion of women who could not afford new clothes was slowly increasing with age. The proportion of women who could not afford new clothes was around 14.0% for the age group 18-24 while the proportion of those aged 65 and over was around 22.2%.

Further, Figure 2.3 shows the age differences within-household at EU level. As shown, around 8.9% of people in the EU aged 16 and over could not afford new clothes for themselves but their household could afford it for all children. In addition, around 6.9% of people in the EU aged 16 and over could not afford two pairs of shoes for themselves but their household could afford it for all children.

Leisure activities

In this part of the article, we focus solely on the household`s or personal inability to afford regular leisure activities due to insufficient recourses (problems of affordability), rather than inability resulting from choices and lifestyle preferences.

Regular participation in a leisure activity (both for children and adults) refers to activities such as sport, cinema, concert, etc. which should occur outside home and which should cost money

- for entrance and/or travel costs (e.g. swimming),

- for purchase costs (e.g. riding a bicycle) or

- for participating costs in an organised play event (e.g. football club fees) .

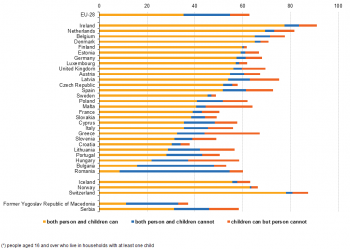

Figure 2.4 shows the percentages of people who lived in households which could not afford a regular leisure activity for all children due to financial reasons by number of children. Households with children are usually financially worse off compared to households without children due to high cost of bringing up children.

As it is shown in the figure, with an increase of the number of children, percentage of people who lived in households which could not afford leisure activities for all children was also increasing (24.1% for one child and 50.7% for four and more children at EU level). However, in Romania and Bulgaria, around half of the observed people who lived in households with one child also lived in household which could not afford leisure activities for that child (53.1% and 45.7% respectively).

In Bulgaria, all people who lived in households with four and more children could not afford leisure activities for all children. While, in Denmark, Luxembourg and Finland less than 6% of households could not afford leisure activities for all children regardless of the number of children in the household.

Observing intra-generational differences, the 2014 EU-SILC survey showed that the main difference between age groups in ability to participate in leisure activities was mainly due to non-financial reasons. More precisely, the proportion of people who were not participated in leisure activities due to other but financial reason was 16.4% for age group 18-24 and 54.1% for people aged 65 and over.

Figure 2.5 shows the inter-generational differences when it comes to the ability to afford leisure activities for household members belonging to different age groups. Compared to the ability to afford new clothes, far fewer people lived in households where both observed person and children could afford regular leisure activities (around 35.3% at EU level).

Among the EU-28, Romania (8.5%) and Bulgaria (15.8%) were countries with the lowest proportion of households where both adults and children could participate in paid leisure activities. While in Ireland (77.5%) and Netherland (69.3%) the highest proportion of both adults and children could participate.

Inter-generational differences were visible when it comes to leisure, too. In Spain and Hungary over 20% of adults could not afford regular leisure activities but they lived in households which could afford it for all children (23.1% and 21.4% respectively). However, in Finland, Sweden and Czech Republic these percentages were below 3% (1.3%, 2.0% and 2.3%).

Deprived adults

Spending a small amount of money without consulting with someone

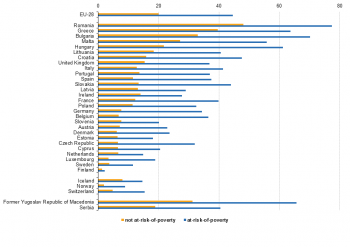

In 2014, 25.2% of women and 23.0% of men in the EU aged 16 and over could not afford to spend a small amount of money on themselves without consulting with someone.

Inability for persons aged 16 and over (further in text – adult) to freely spend money each week on themselves (e.g. to go to the movies, to buy a gift for a friend, to go to the hairdresser, etc.) without consulting with someone, could show possible intra-household (dis)allocation of resources.

Figure 3.1 shows the percentages of people who could not afford to spend a small amount of money by gender. Among both EU and non-EU Member States (except Denmark where the percentages are the same: 9%), women were more vulnerable, i.e. more women than men could not afford to spend money freely.

Observing gender differences, neither age nor education changes the pattern – in all cases women were more money-deprived. However, in the case of most frequent activity status , unemployed men were, in more than half of all observed countries, more deprived than women. Also, based on the 2014 EU-SILC survey, women were more deprived if they do not live with a partner in a same household (at EU28 level).

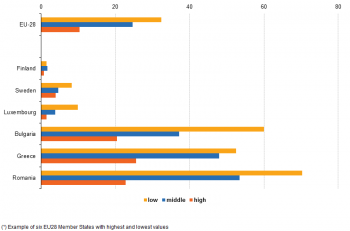

Living in a household which is at-risk-of-poverty was increasing the inability of spending money without consulting with someone (see Figure 3.2). In all observed countries, except Finland, the proportions of people aged 16 and over who were not able to freely spend money were significantly higher for those who lived in households which were at risk of poverty compared to those who did not (20.0% in not at-risk and 44.6% in at-risk-of poverty households, at EU level).

In Romania and Bulgaria the proportion of people who were not able to spend money without consulting with someone regardless of monetary poverty was relatively high compared to other EU Member States (48.1% and 33.0% for those in not at-risk and 77.4% and 70.2% for those in at-risk-of-poverty households respectively). On the other hand, in Finland only around 1.4% of adults in total was not able to spend small amount of money without consulting someone (1.2% in not at-risk and 2.1% in at-risk-of poverty households).

Even though the education level does not play a significant role when it comes to the gender differences, in general, it was observed that it had a huge impact on the ability of people to spend money without consulting with someone. In all countries people with the lowest attained education level had the highest inability to freely spend money.

Countries with the smallest differences between low and high educated were Estonia and Denmark while countries with the biggest differences were Luxembourg and Czech Republic. Among the countries with the low educated adults who could not spend money without consulting someone was Finland (1.5%). In Greece almost half of the high educated adults (48.8%) could not freely spend their money (see Figure 3.3).

When analysing the results, one must take into a consideration the link between monetary poverty and the ability of adult to spend money without consulting with someone (see Figure 3.2). Since educational levels play a significant role when it comes to monetary poverty (see ilc_li07), the correlation of results is possible.

Data sources and availability

The data used in this section is primarily derived from the EU-SILC. The EU-SILC is carried out annually and is the main survey that measures income and living conditions in Europe, and is the main source of information used to link different aspects of Quality of Life at household and individual level.

Material deprivation refers to several different material deprivation variables (as part of 2014 SILC ad-hoc module) which relate to the household (as a whole), “adults” (people aged 16 and over) and children (all household members aged between 1 and 15). Observed variables, among others, are related to financial stress and durables, and leisure and social activities.

Income refers to income levels (‘Mean and median income by age and sex’), monetary poverty (‘at-risk-of-poverty rate (AROP) by poverty threshold and age’). Material conditions refers to material deprivation (‘severely materially deprived’ people). Material deprivation ad-hoc module refers to an additional set of variables conducted in 2014 survey year.

The size of the initial sample is reduced based on the number of households which do not have children of this age. Also, some items could be inapplicable or answers could be missing, which reduces the sample again. When it comes to data collected at personal level (taking into account the characteristics of the information), only personal interviews are allowed. This means that proxy interviews are not taken into account which, in some cases, could reduce the size of the sample used in calculations.

Context

At the Laeken European Council in December 2001, European heads of state and government endorsed a first set of common statistical indicators for social exclusion and poverty that are subject to a continuing process of refinement by the indicators sub-group (ISG) of the social protection committee (SPC). These indicators are an essential element in the open method of coordination (OMC) to monitor the progress made by the EU’s Member States in alleviating poverty and social exclusion.

EU-SILC is the reference source for EU statistics on income and living conditions and, in particular, for indicators concerning social inclusion. In the context of the Europe 2020 strategy, the European Council adopted in June 2010 a headline target for social inclusion — namely, that by 2020 there should be at least 20 million fewer people in the EU at risk of poverty or social exclusion than there were in 2008. The EU-SILC is the source used to monitor progress towards this headline target, which is measured through an indicator that combines the at-risk-of-poverty rate, the severe material deprivation rate, and the proportion of people living in households with very low work intensity — see the article on social inclusion statistics for more information.

See also

- Name of related Statistics Explained article

- Name of related online publication in Statistics Explained (online publication)

- Name of related Statistics in focus article in Statistics Explained

- Subtitle of Statistics in focus article=PDF main title - Statistics in focus x/YYYY

Further Eurostat information

Data visualisation

- Regional Statistics Illustrated - select statistical domain 'xxx' (= Agriculture, Economy, Education, Health, Information society, Labour market, Population, Science and technology, Tourism or Transport) (top right)

Publications

Publications in Statistics Explained (either online publications or Statistics in focus) should be in 'See also' above

Main tables

- Title(s) of second level folder (if any)

- Title(s) of third level folder (if any)

Database

- Title(s) of second level folder (if any)

- Title(s) of third level folder (if any)

Dedicated section

Methodology / Metadata

<link to ESMS file, methodological publications, survey manuals, etc.>

- Crime and criminal justice (ESMS metadata file — crim_esms)

- Title of the publication

Source data for tables, figures and maps (MS Excel)

Other information

<Regulations and other legal texts, communications from the Commission, administrative notes, Policy documents, …>

- Regulation (EC) No 1737/2005 (generating url [http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:32005R1737:EN:NOT Regulation (EC) No 1737/2005]) of DD Month YYYY on ...

- Directive 2003/86/EC (generating url [http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:32003L0086:EN:NOT Directive 2003/86/EC]) of DD Month YYYY on ...

- Commission Decision 2003/86/EC (generating url [http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:32003D0086:EN:NOT Commission Decision 2003/86/EC]) of DD Month YYYY on ...

<For other documents such as Commission Proposals or Reports, see EUR-Lex search by natural number>

<For linking to database table, otherwise remove: {{{title}}} ({{{code}}})>

External links

Notes

- ↑ Age refers to the age at the end of the income reference period.

- ↑ Further in text, term “children” refers to children aged between 1 and 15.

- ↑ People at risk of poverty or social exclusion by age and sex (ilc_peps01).

- ↑ Further in text, term “meal” refers to meat, chicken or fish or vegetarian equivalent.

- ↑ If the household does not have at its disposal a minimum number of rooms considered adequate, it is defined as overcrowded

- ↑ Term “space” refers to a suitable place for children (going to school) to study or do their homework.

[[Category:<Subtheme category name(s)>|Name of the statistical article]] [[Category:<Statistical article>|Name of the statistical article]]

Delete [[Category:Model|]] below (and this line as well) before saving!