Archive:The EU in the world - population

- Data extracted in March 2015. Most recent data: Further Eurostat information, Main tables and Database. Planned article update: May 2016.

Source: Eurostat (for more information see table 1 below)

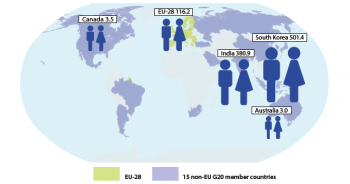

The infographic shows EU‑28 as well as the two G20 members with the highest values and the two with the lowest values. Note that the size of the symbols does not show a precise representation of the underlying data values, but illustrates the highest and lowest values.

(%)

Source: Eurostat (demo_gind) and the World Bank (Health Nutrition and Population Statistics)

Source: Eurostat (demo_gind) and (tps00003), the World Bank (Health Nutrition and Population Statistics), the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAOSTAT: Inputs) and the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (World Population Prospects: the 2012 Revision)

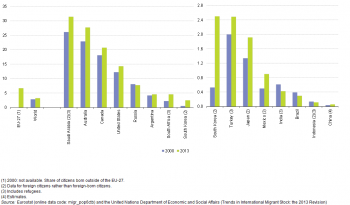

(% of total population)

Source: Eurostat (demo_pjangroup) and the World Bank (Health Nutrition and Population Statistics)

(population aged 0–14 as a percentage of the population aged 15–64)

Source: Eurostat (demo_pjanind) and the World Bank (Health Nutrition and Population Statistics)

(population aged 65 or more as a percentage of the population aged 15–64)

Source: Eurostat (demo_pjanind) and the World Bank (Health Nutrition and Population Statistics)

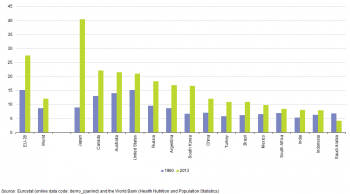

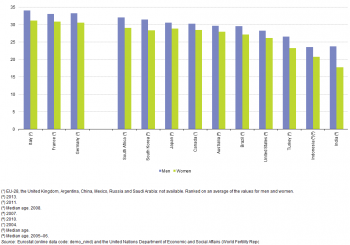

(years)

Source: Eurostat (demo_nind) and the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (World Fertility Report 2012)

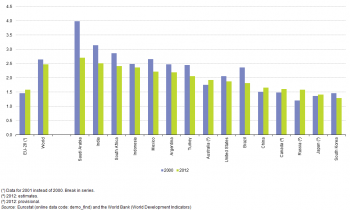

(average number of births per woman)

Source: Eurostat (demo_find) and the World Bank (World Development Indicators)

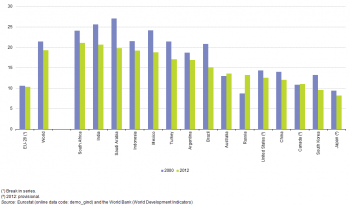

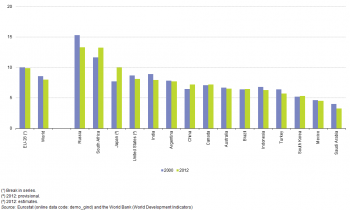

(per 1 000 population)

Source: Eurostat (demo_gind) and the World Bank (World Development Indicators)

(per 1 000 population)

Source: Eurostat (demo_gind) and the World Bank (World Development Indicators)

(per 1 000 population)

Source: Eurostat (demo_gind) and the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (World Population Prospects: the 2012 Revision)

(%)

Source: Eurostat (migr_pop6ctb) and the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (Trends in International Migrant Stock: the 2013 Revision)

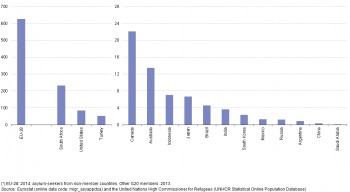

(thousand applicants)

Source: Eurostat (migr_asyappctza) and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR Statistical Online Population Database)

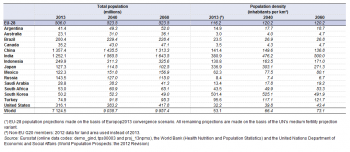

Source: Eurostat (demo_gind), (tps00003) and (proj_13npms), the World Bank (Health Nutrition and Population Statistics) and the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (World Population Prospects: the 2012 Revision)

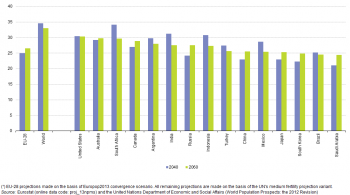

(population aged 0–14 as a percentage of the population aged 15–64)

Source: Eurostat (proj_13npms) and the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (World Population Prospects: the 2012 Revision)

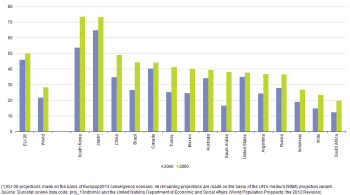

(population aged 65 or more as a percentage of the population aged 15–64)

Source: Eurostat (proj_13ndbims) and the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (World Population Prospects: the 2012 Revision)

This article is part of a set of statistical articles based on Eurostat’s publication The EU in the world 2015.

This article focuses on population structure and population developments in the European Union (EU) and in the 15 non-EU members of the Group of Twenty (G20). It covers key demographic indicators and gives an insight of the EU’s population in comparison with the major economies in the rest of the world, such as its counterparts in the so-called Triad — Japan and the United States — and the BRICS composed of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa.

Main statistical findings

Population size and population density

Between 1960 and 2013 the share of the world’s population living in G20 members fell from 73.8 % to 64.3 %

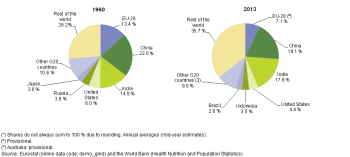

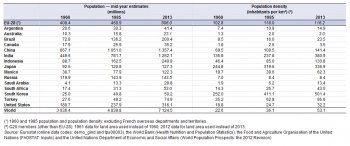

In 2013, the world’s population reached 7.1 billion inhabitants and continued to grow. Although all members of the G20 recorded higher population levels in 2013 than they did more than 50 years before, between 1960 and 2013 the share of the world’s population living in G20 members fell from 73.8 % to 64.3 %. Russia recorded the smallest overall population increase (19.7 %) during these 53 years, followed by the EU-28 (23.9 %), while the fastest population growth among G20 members was recorded in Saudi Arabia, with a seven-fold increase.

The most populous countries in the world in 2013 were China and India, together accounting for almost 37 % of the world’s population (see Figure 1) and 57 % of the population in the G20 members. The population of the EU-28 in 2013 was 506.0 million inhabitants, 7.1 % of the world’s total.

As well as having the largest populations, Asia had the most densely populated G20 members, namely South Korea, India and Japan — each with more than 300 inhabitants per km² (of land area), followed by China and Indonesia and then the EU-28 with more than 100 inhabitants per km².

Population age structure

Ageing society represents a major demographic challenge for many economies and may be linked to a range of issues, including, persistently low levels of fertility rates and significant increases in life expectancy during recent decades.

Figure 2 shows how different the age structure of the EU-28’s population is from the average for the whole world. Most notably the largest shares of the world’s population are among the youngest age classes, reflecting a population structure that is younger, whereas for the EU-28 the share of the age groups below those aged 45–49 years generally gets progressively smaller approaching the youngest cohorts. The structure in the EU-28 reflects falling fertility rates over several decades and a modest increase in the most recent decade, combined with the impact of the baby-boomer cohorts on the population structure (resulting from high fertility rates in several European countries up to the mid-1960s). This overall pattern of a progressively smaller share of the population in the younger age groups in the EU-28 stops at the age group 10–14, below which the share stabilises in the age group 5–9 and increases slightly in the age group 0–4. Another notable difference is the greater gender imbalance within the EU-28 among older age groups than is typical for the world as a whole. Some of the factors influencing age structure are presented in the rest of this article and the article on health, for example, fertility, migration and life expectancy.

Japan had by far the highest old-age dependency ratio in 2013

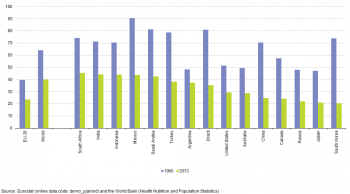

The young and old age dependency ratios shown in Figures 3 and 4 summarise the level of support for younger persons (aged less than 15 years) and older persons (aged 65 years and over) provided by the working age population (those aged 15–64 years). In 2013, the young-age dependency ratio ranged from 20.4 % in South Korea to more than double this ratio in South Africa (45.4 %), with the ratio in the EU-28 (23.6 %) lower than in most G20 members. By far the highest old-age dependency ratio in 2013 was the 40.5 % observed in Japan, indicating that there were two people aged 65 and over for every five people aged 15 to 64 years; the next highest old-age dependency ratio was 27.5 % in the EU-28.

The fall in the young-age dependency ratio for the EU-28 between 1960 and 2013 more than cancelled out an increase in the old-age dependency ratio. Most of the G20 members displayed a similar pattern, with two exceptions: in Japan the increase in the old-age dependency ratio exceeded the fall in the young-age dependency ratio; in Saudi Arabia both the young and old-age dependency ratios were lower in 2013 than in 1960, reflecting a large increase in the working age population in this country.

Marriage

Indicators for marriage provide information in relation to family formation. Marriage, as recognised by the law of each country, has long been considered as marking the formation of a family unit. Among the G20 members for which data are available (see Figure 5) there was a large range in the average age at the time of first marriage, particularly for women. Outside of the EU, for men the average ranged from just under 24 years in India and Indonesia (both based on the median age rather than the mean) to 32.0 years in South Africa (also based on the median age). In all three of the G20 EU Member States shown in Figure 5, the average age at first marriage for men was higher than in any of the other G20 members, in all three cases around 33–34 years. A similar pattern could be observed for women. Outside of the EU, the averages for the G20 members ranged from 26.1 years in the United States (also based on the median age) to 29.0 years in South Africa, with Turkey, Indonesia and India below this range and the three available G20 EU Member States above this range. In all of the members shown in Figure 5 the average age for men at first marriage was higher than for women, with the largest gender differences reported for India and the smallest for Japan, Australia and Canada.

Natural population change

The fertility rate is the mean number of children who would be born to a woman during her lifetime, if she were to spend her childbearing years conforming to the age-specific fertility rates that have been measured in a given year. Fertility rates in industrialised countries have fallen substantially over several decades and have been accompanied by a postponement of motherhood, which may in part be attributed to increases in the average length of education of women, increased female employment rates, and changes in attitudes towards the position of women within society and the roles of men and women within families. In the most recent decade for which data are available, a slight increase in the fertility rate for the EU-28 was observed.

Fertility rates fell between 2000 and 2012 in more than half of all of the G20 members, most notably in Saudi Arabia, India, Brazil, South Africa and Mexico. Russia recorded the largest increase, rising from 1.2 births per woman in 2000 to 1.6 births per woman in 2012. The average fertility rate in the EU-28 in 2012 was 1.6 births per woman, lower than in all of the other G20 members except for Japan and South Korea.

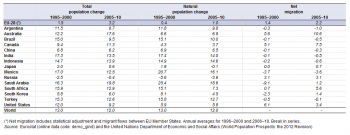

There are two distinct components of population change: the natural change that results from the difference between the number of live births and the number of deaths; and the net effect of migration, in other words, the balance between people coming into and people leaving a territory. Since many countries do not have accurate figures on immigration and emigration, net migration may be estimated as the difference between the total population change and the natural population change.

The crude birth rate in the EU-28 was among the lowest across the G20 members

The crude birth rate (the ratio of the number of births to the population) in the EU-28 in 2012 was slightly lower than in 2000, and remained among the lowest across the G20 members, with only South Korea and Japan recording lower birth rates. Crude birth rates recorded in India and South Africa in 2012 were around double the average rate for the EU-28.

When the death rate exceeds the birth rate there is negative natural population change; this situation was experienced in Japan in 2012, while birth and death rates were balanced in Russia. The reverse situation, natural population growth due to a higher birth rate, was observed for all of the remaining G20 members (see Figures 7 and 8) with the largest differences recorded in Saudi Arabia, Mexico, Indonesia, India and Turkey. The highest crude death rates (the ratio of the number of deaths to the population) were recorded in Russia and South Africa, in the latter case reflecting in part an HIV/AIDS epidemic which has resulted in a high number of deaths among relatively young persons, such that that the difference between crude birth and death rates in South Africa was below the world average despite the high birth rate.

Migration and asylum

The combined effect of natural population change and net migration including statistical adjustment (which refers to changes observed in the population figures which have not been attributed to births, deaths, immigration or emigration) can be seen in the total change in population levels. During the five years between 2005 and 2010 all of the G20 members, except Russia, experienced an increase in their population numbers. Russia’s declining population resulted from net inward migration being smaller than the negative natural population change. Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Mexico and Turkey experienced negative net migration that was less than the positive increase from natural population change. The EU-28, Australia, Canada, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, South Korea and the United States experienced the cumulative effects of positive natural population change and net migration. This situation was broadly similar to that observed 10 years earlier, between 1995 and 2000, with the notable exception of Saudi Arabia which had then experienced relatively strong outward net migration in contrast to the more recent pattern for net inward migration, although in 1995–2000 this was outweighed by higher natural population growth.

More than one quarter of people living in Australia were foreign-born while close to one third of residents in Saudi Arabia were foreign citizens

Some 6.7 % of the population living in the EU-27 in 2013 had been born outside of the EU, around 33.5 million people. While the share in Russia (7.7 %) was just above the share in the EU, that in the United States (14.3 %) was more than twice as high as the share in the EU, in Canada (20.7 %) more than three times as high, and in Australia (27.7 %) and Saudi Arabia (31.4 %; foreign citizens) more than four times as high. The G20 members with the lowest shares of foreign-born citizens were Indonesia (foreign citizens) and China. Between 2000 and 2013, the share of foreign-born citizens increased in most G20 members, the exceptions being Russia, India, Brazil and Indonesia (no data available for the EU).

In 2013, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees reported that there were 1.17 million asylum applicants across the world. Asylum is a form of protection given by a state on its territory. It is granted to a person who is unable to seek protection in their country of citizenship and/or residence in particular for fear of being persecuted for various reasons (such as race, religion or opinion).

In 2013 there were 435 thousand asylum applicants (from non-member countries) in the EU-28, increasing to 626 thousand in 2014. Among those seeking asylum in the EU-28 in 2014, the highest number were from Syria (122 thousand), followed by Afghanistan, Kosovo, Eritrea and Serbia (each accounting for between 31 and 41 thousand asylum seekers). The highest numbers of asylum applicants into the EU-28 from G20 members came from Russia (19.7 thousand), China (5.2 thousand) and Turkey (5.1 thousand); note that the data for China include applicants from Hong Kong.

Figure 10 shows that aside from the EU-28, there were relatively high numbers of asylum seekers in 2013 in South Africa (many of whom originated from Zimbabwe, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Ethiopia) and to a lesser extent in the United States and Turkey.

Future population: population projections

The global number of inhabitants is projected to reach almost 10 billion by 2060

The latest United Nations population projections suggest that the pace at which the world’s population is expanding will slow in the coming decades; however, the total number of inhabitants is projected to reach almost 10 billion by 2060, representing an overall increase of 39.8 % compared with 2013. The slowdown in population growth that this represents will be particularly apparent for developed and emerging economies as the number of inhabitants within the G20 — excluding the EU — is projected to increase by 15.0 % between 2013 and 2060 while the EU-28’s population is projected (by Eurostat) to increase by 3.5 % over the same period. The population of many developing countries, in particular those in Africa, is likely to continue growing at a rapid pace. Among the G20 members, the fastest population growth between 2013 and 2060 is projected to be in Australia and Saudi Arabia, while the populations of Russia, Japan, China and South Korea are projected to be smaller by 2060 than they were in 2013. Despite the projection of rapid population growth, Australia is expected to remain the least densely populated G20 member through until 2060 when it will draw level with Canada.

With relatively low fertility rates the young-age dependency ratio (population aged less than 15 as a percentage of the population aged 15 to 64) is projected to be lower in 2060 than it was in 2013 in several G20 members, dropping by more than 10 percentage points in Mexico, Saudi Arabia, India, Indonesia, South Africa, Turkey and Brazil. Projected increases for this ratio are relatively small, peaking at 5.3 percentage points in Russia. In the EU-28, the young-age dependency ratio is projected to increase from 23.6 % in 2013 to 26.5 % by 2060, but will remain well below the world average of 33.1 %, as it will in all G20 members.

Old-age dependency ratios (population aged 65 or more as a percentage of the population aged 15 to 64) are projected to continue to rise in all G20 members, suggesting that there will be an increasing burden to provide for social expenditure related to population ageing (for example, for pensions, healthcare and institutional care). The EU-28’s old-age dependency ratio is projected to increase from 27.5 % in 2013 to 50.2 % by 2060, when it is projected to be 21.9 percentage points above the world average, but considerably lower than in South Korea or Japan.

Data sources and availability

The statistical data in this article were extracted during March 2015.

The indicators are often compiled according to international — sometimes global — standards. Although most data are based on international concepts and definitions there may be certain discrepancies in the methods used to compile the data.

EU data

Most of the indicators presented for the EU have been drawn from Eurobase, Eurostat’s online database. Eurobase is updated regularly, so there may be differences between data appearing in this article and data that is subsequently downloaded.

G20 members from the rest of the world

For the 15 non-EU G20 members, the data presented have been extracted from a range of international sources, namely the Food and Agricultural Organisation, the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, and the World Bank. For some of the indicators shown a range of international statistical sources are available, each with their own policies and practices concerning data management (for example, concerning data validation, correction of errors, estimation of missing data, and frequency of updating). In general, attempts have been made to use only one source for each indicator in order to provide a comparable analysis between the members.

Context

As a population grows or contracts, its structure changes. In many developed economies the population’s age structure has become older as post-war baby-boom generations reach retirement age. Furthermore, many countries have experienced a general increase in life expectancy combined with a fall in fertility, in some cases to a level below that necessary to keep the size of the population constant in the absence of migration. If sustained over a lengthy period, these changes can pose considerable challenges associated with an ageing society which impact on a range of policy areas, including labour markets, pensions and the provision of healthcare, housing and social services.

See also

Further Eurostat information

Publications

- The European Union and the African Union — 2014 edition

- Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM) — A statistical portrait — 2014 edition

- The EU in the world 2014

- Key figures on the enlargement countries — 2014 edition

- Pocketbook on Euro-Mediterranean statistics — 2013 edition

- The EU in the world 2013

- The European Union and the BRIC countries

- The European Union and the Republic of Korea — 2012

- Demographic outlook 2010

Main tables

- Population (t_populat), see:

- Demography (t_pop)

- Demography - National data (t_demo)

- Population (t_demo_pop)

- Population density (tps00003)

- Population (t_demo_pop)

- Demography - National data (t_demo)

Database

- Population (demo_pop), see:

- Population on 1 January by age and sex (demo_pjan)

- Population on 1 January by five years age groups and sex (demo_pjangroup)

- Population on 1 January by sex, country of birth and broad group of citizenship (migr_pop6ctb)

- Population on 1 January: Structure indicators (demo_pjanind)

- Fertility (demo_fer), see:

- Fertility indicators (demo_find)

- Marriage indicators (demo_nind)

- EUROPOP2013 - Population projections at national level (proj_13n)

- Projected population (proj_13np)

- Asylum and Dublin statistics (migr_asy)

- Applications (migr_asyapp)

- Asylum and first time asylum applicants by citizenship, age and sex Annual aggregated data (rounded) (migr_asyappctza)

- Applications (migr_asyapp)

Dedicated section

- Asylum and managed migration

- Employment and social policy — youth indicators

- GDP and beyond

- Population

Source data for tables and figures (MS Excel)

![]() Population: tables and figures

Population: tables and figures

External links

- Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations FAO

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe UNECE

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees UNHCR

- World Bank