Archive:The EU in the world - economy and finance

- Data from February 2014. Most recent data: Further Eurostat information, Main tables and Database. Planned article update: May 2015.

This article is part of a set of statistical articles based on Eurostat’s publication The EU in the world 2014.

The article presents indicators from various areas, such as national accounts, government finance, exchange rates and interest rates, consumer prices, and the balance of payments in the European Union (EU) and in the 15 non-EU countries from the Group of Twenty (G20). It gives an insight into the EU’s economy in comparison with the major economies in the rest of the world, such as its counterparts in the so-called Triad — Japan and the United States — and the BRICS composed of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa.

(%) - Source: Eurostat (nama_gdp_c) and the United Nations Statistics Division (National Accounts Main Aggregates Database)

(%, based on current international PPP) - Source: Eurostat (nama_gdp_c) and the World Bank (World Development Indicators)

(2002 = 100) - Source: Eurostat (nama_gdp_k) and the United Nations Statistics Division (National Accounts Main Aggregates Database)

(% of total) - Source: Eurostat (nama_nace10_c) and the United Nations Statistics Division (National Accounts Main Aggregates Database)

(% of GDP) - Source: Eurostat (gov_a_main) and (gov_dd_edpt1) and the International Monetary Fund (World Economic Outlook, 2013)

(% of GDP) - Source: Eurostat (gov_a_main) and (gov_dd_edpt1) and the International Monetary Fund (World Economic Outlook, 2013)

(% of GDP) - Source: Eurostat (gov_a_main) and (gov_dd_edpt1) and the International Monetary Fund (World Economic Outlook, 2013)

(% of GDP) - Source: Eurostat (gov_a_main) and (gov_dd_edpt1) and the International Monetary Fund (World Economic Outlook, 2013)

(EUR billion) - Source: Eurostat (bop_q_eu), (bop_q_euro) and (nama_gdp_c) and the International Monetary Fund (World Economic Outlook, 2013)

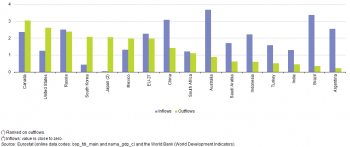

(% of GDP) - Source: Eurostat (bop_fdi_main) and (nama_gdp_c) and the World Bank (World Development Indicators)

(% of GDP) - Source: Eurostat (bop_fdi_main) and (nama_gdp_c) and the World Bank (World Development Indicators)

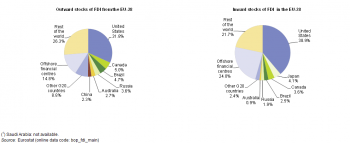

(% of total) - Source: Eurostat (bop_fdi_main)

(% of total) - Source: Eurostat (bop_fdi_main)

(annual change, %) - Source: Eurostat (prc_hicp_aind) and the International Monetary Fund (World Economic Outlook, 2013 and International Financial Statistics)

(annual change, %) - Source: Eurostat (prc_hicp_aind) and the International Monetary Fund (World Economic Outlook, 2013 and International Financial Statistics)

Main statistical findings

National accounts (GDP)

G20 members accounted for 85.7 % of the world’s GDP in 2012

In 2012, the total economic output of the world, as measured by GDP, was valued at EUR 56 577 billion, of which the G20 members accounted for 85.7 %, 4.2 percentage points less than in 2002. The EU-28 accounted for a 22.9 % share of the world’s GDP in 2012, while the United States’ share was 22.3 % — see Figure 1; note these relative shares are based on current price series in euro terms, reflecting bilateral exchange rates. The Chinese share of world GDP rose from 4.3 % in 2002 to 11.5 % in 2012, moving ahead of Japan (8.2 % share). To put the rapid pace of recent Chinese growth into context, in current price terms China’s GDP in 2012 was EUR 4 970 billion higher than it was in 2002, an increase equivalent to the combined GDP in 2012 of the seven smallest G20 economies (Mexico, South Korea, Indonesia, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Argentina and South Africa).

Figure 2 shows an analysis of the world share of GDP accounted for by each of the G20 members for 2002 and 2012 — note that these figures are in purchasing power parities terms (in other words, they are adjusted for price level differences). On this basis, the relative importance of China within the global economy was considerably higher, accounting for 14.2 % of the world’s output in 2012, which was more than two thirds of the share attributed to the EU-28 (19.9 %).

Figure 3 shows the real growth rate (based on constant price data) of GDP in the EU-28 compared with the other G20 members — note the different scales used for the different parts of the figure. The lowest rates of change were generally recorded by the developed economies such as Japan, the EU-28, the United States and Canada, while the highest rates were recorded in the two Asian economies of China and India.

Among the G20 members, the highest gross national income (GNI) per capita in 2010 was recorded in the United States; note that the conversion to United States dollars used for this indicator in Figure 4 is based on purchasing power parities rather than market exchange rates and so reflects differences in price levels between countries. In comparison with average GNI for the world (USD 12 186 per capita), the average level of income in the United Sates was 4.3 times as high. Australia, Canada and Japan recorded average GNI per capita that was more than three times the world average, followed by the EU-28, South Korea and Saudi Arabia where it was more than twice as high. By contrast, five G20 members recorded GNI per capita levels around or below the world average, namely Brazil and South Africa, China, Indonesia and India.

In broad terms, countries with relatively low GNI per capita recorded relatively high economic growth over the 10 years from 2002–12; this was most notably the case in China and India. By contrast, countries with relatively high GNI per capita recorded fairly low economic growth over the same period; this was most notably the case in Japan. Nevertheless, Saudi Arabia reported an atypical pattern of development, combining a relatively high level of GNI per capita (that was more than double the world average) with growth in GDP that averaged 6.7 % per annum (the third highest growth rate during the period 2002–12 among the G20 members).

Economic structure

In 2012, agriculture, forestry and fishing contributed 10 % or more to GDP in India, Indonesia and China

The economic structure of the G20 members varies most greatly in relation to the relative importance of agriculture, forestry and fishing and, to a lesser extent, the relative share of industry — see Figure 5; note that the data for the EU-28 and the euro area (EA-18) are based on the NACE Rev. 2 activity classification (compatible with ISIC Rev.4), whereas the data for the other G20 members are based on ISIC Rev.3.

In 2012, agriculture, forestry and fishing contributed 10 % or more of GDP in India, Indonesia and China, whereas its contribution was 2 % or less in the United States, Japan, Canada, the EU-28 and Australia. Industry (including mining and quarrying; manufacturing; electricity, gas and water supply) contributed more than half of Saudi Arabia’s GDP (58 %) and more than one third of total GDP in China, Indonesia and South Korea, while in Canada, the EU-28, India and the United States its contribution was less than one fifth of the total. The contribution of construction to GDP was less than 10 % in all of the G20 members shown in Figure 5, other than in Indonesia where its share just reached double figures.

The contribution of distributive trades, hotels and restaurants, transport, information and communication services to the overall economy varied least across the G20 members, ranging from 31.8 % in Turkey to 16.3 % in China, with Saudi Arabia outside this range (12.9 %). In the United States, Canada and the euro area (EA-18), other services (which includes financial and business services, as well as a range of services often associated with public sector provision, for example, education or health) contributed more than half of total GDP, while the EU-28 and Australia recorded contributions from other services just below this level. By contrast, other services contributed a share between one quarter and a little over one third of GDP in Mexico, Turkey, India, Russia and China and even less in Saudi Arabia (22.7 %) and Indonesia (18.0 %).

General government finances

Most G20 members had a government deficit in 2012

The financial and economic crisis of 2008–09 resulted in considerable media exposure for government finance indicators. The government surplus/deficit (public balance) measures government borrowing/lending for a particular year; in other words, borrowing to finance a deficit or lending made possible by a surplus. General government debt refers to the consolidated stock of debt at the end of the year. Typically, both of these indicators are expressed in relation to GDP; in Figure 6 the size of each bubble reflects the absolute size of general government debt, which ranged in 2012 from EUR 20.5 billion in Saudi Arabia to EUR 12 989 billion in the United States.

Most G20 members had a government deficit in 2012; only three— Russia, South Korea and Saudi Arabia — recorded a surplus. Generally G20 members with the highest government deficits had the highest levels of government debt and this was notably the case for Japan and to a lesser extent the United States. Equally, the two members with the lowest levels of government debt, namely Saudi Arabia and Russia, were among the few countries with a government surplus in 2012.

The importance of the general government sector in the economy may be measured in terms of the average of general government revenue and expenditure in relation to GDP. The highest such ratios for G20 members in 2012 were 47.4 % in the EU-28, followed by 44.3 % in Saudi Arabia and 42.3 % in Argentina. The lowest ratio was in Indonesia (18.9 %); note the data for Mexico and South Korea relate only to the expenditure and revenue of central government as opposed to general government which covers all levels of public administration.

Subtracting expenditure from revenue results in the government surplus/deficit. Comparing data for 2002 with 2012 (see Table 1), Saudi Arabia’s government moved from a deficit to a surplus, Russia and South Korea’s surpluses contracted, while Canada and Australia moved from a balanced budget and a government surplus respectively to a government deficit. At the same time, Turkey, Argentina, India, Brazil and China’s government deficits contracted and the government deficits of Mexico, Indonesia, Japan, South Africa and the United States expanded, as did the deficit for the EU Member States (comparing EU-28 data for 2012 with EU-27 data for 2002).

Table 2 provides more detailed information concerning the development of the government surplus/deficit between 2002 and 2012. In 2007, just before the onset of the financial and economic crisis, seven G20 members recorded a government surplus, generally less than 2.5 % of GDP with Russia (6.8 %) and Saudi Arabia (15.0 %) above this level. The deficits in the remaining G20 members were less than 2.5 % of GDP except in Brazil and the United States (both 2.7 % of GDP) and India (4.4 %). Already in 2008 the number of G20 members reporting a surplus stood at just three: namely, Saudi Arabia, Russia and South Korea, while the deficits reported for India and the United States had increased substantially. In 2009, none of the G20 members reported a government surplus, although South Korea maintained a balanced budget; South Korea was the only G20 member not to report a budget deficit during the financial and economic crisis. In India the deficit in 2009 contracted slightly, whereas in all other G20 members the deficit grew wider or a surplus turned into a deficit. The pace of change was particularly rapid in Russia and Saudi Arabia, where government surpluses recorded in 2008 turned into deficits of -6.3 % and -4.1 % of GDP respectively in 2009. In 2010, there were signs that the pace of government borrowing was generally no longer expanding, as only Australia and Canada reported their budget deficits (relative to GDP) increasing compared with the previous year, while in Saudi Arabia, South Korea and Russia, a government surplus was reported.

Two of the three G20 members recording government surpluses in 2012 saw their levels of debt fall between 2002 and 2012, namely Saudi Arabia and Russia. Other G20 countries with a lower ratio of general government gross debt to GDP in 2012 than in 2002 included Brazil, India, Turkey, Indonesia and Argentina. All the remaining G20 members shown in Table 1 recorded higher general government gross debt relative to GDP in 2012 than in 2002, most notably in Japan and the United States whose ratios of gross debt to GDP passed 200 % and 100 % of GDP respectively. Figure 7 provides an analysis of the change in government gross debt levels between 2007 — just before the onset of the financial and economic crisis — and 2012. During this period, government debt relative to GDP fell in Turkey, India, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia and Argentina, while it increased in all other G20 members, most notably in the United States and Japan.

Balance of payments

Many of the Asian members of the G20 recorded current account surpluses in 2012

The current account of the balance of payments provides information on international trade in goods and services (see the article on international trade for more details), as well as income from employment and investment and current transfers with the rest of the world. Among the G20 members, the largest current account surplus in 2012 in absolute terms was EUR 150.3 billion for China, while in relative terms the current account surplus peaked in Saudi Arabia at 23.2 % of GDP. The largest current account deficit in 2012 was EUR 342.8 billion for the United States, while South Africa’s deficit represented 6.3 % of GDP. Argentina, Canada, India, Indonesia and South Africa’s current account balance moved from a surplus to a deficit between 2002 and 2012, while the EU-28 moved from a deficit to a surplus.

Foreign direct investment

The highest inflows of FDI were recorded in the emerging markets and resource rich countries

Foreign direct investment (FDI) is characterised by investment in new foreign plant/offices, or by the purchase of existing assets that belong to a foreign enterprise. FDI differs from portfolio investment as it is made with the purpose of having control or an effective voice in the management of the direct investment enterprise.

The global financial and economic crisis had a major impact on the EU-27’s FDI flows: as a percentage of GDP inflows and outflows dropped from a peak of 8 % in 2007 to below 6 % in 2008, 2009, 2010 and 2012. The impact of the crisis on FDI flows was in no way restricted to the EU, with several other G20 members reporting a fall in flows (relative to GDP), notably Canada where the ratio fell for three successive years from a high of 13 % in 2007 to 4 % by 2010. At the height of the crisis, in 2009, FDI flows relative to GDP fell in nearly all G20 members, the rare exceptions being Mexico, South Africa and Saudi Arabia. In 2010, several G20 members recorded increased FDI flows relative to GDP, although both South Africa and Saudi Arabia recorded falls of more than 2 percentage points and smaller falls were recorded for five other G20 members outside of the EU. Saudi Arabia’s falling FDI flows continued into 2011 (-3.3 percentage points), whereas in most other G20 members the level of flows remained relatively stable, the largest increase being a rise of 1.1 percentage points in Canada, recovering some of the reductions seen over the previous three years. The latest data, namely for 2012, continued this pattern with the level of flows remaining relatively stable: the biggest falls in FDI flows relative to GDP were reductions of 1.2 percentage points in Australia and 1.5 percentage points in Russia, while the highest increase was in South Africa (up 1.3 percentage points). FDI flows relative to GDP were contained within a fairly narrow range in 2012 across all of the G20 members for which data are shown in Figure 10, ranging from a low of 3.9 % in the United States to a high of 5.4 % in Canada.

Among the G20 members, FDI outflows exceeded inflows in 2012 in Japan, South Korea, the United States, Canada and Mexico. Relative to GDP, the highest inflows of FDI were recorded in Australia, Brazil and China, a mixture of emerging markets and resource rich countries.

EU-27 FDI flows are dominated by the United States which accounted for close to half (46.6 %) of the EU-27’s inward FDI in the period 2010–12 and more than one quarter (27.8 %) of its FDI outflows. As a whole, G20 countries (excluding Saudi Arabia) accounted for 63.1 % of FDI outflows from the EU-27 between 2010 and 2012 and 60.6 % of its inflows. A large part of the remainder was FDI flows with offshore financial centres (an aggregate composed of 38 financial centres across the world), as well as with developed countries outside of the G20, notably Switzerland. An analysis of end of year FDI stocks — see Figure 12 — presents a broadly similar picture to that in terms of flows, with the United States the main partner for the EU along with offshore financial centres. Among the G20 members, Brazil, Russia, Canada and Australia appeared alongside the United States at the top of a ranking for origins and destinations of EU-27 FDI stocks; they were joined by China as a destination for EU-27 FDI and Japan as an origin for FDI in the EU-27.

Consumer prices, interest and exchange rates

In nearly all G20 members interest rates were lower in 2012 than 10 years earlier

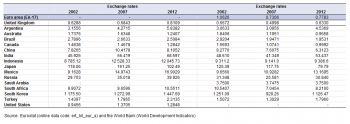

Figure 13 shows the annual rate of change in consumer price indices (CPIs) between 2002 and 2012 for a selection of G20 members and the world. For most of this period Japan recorded negative annual inflation rates, indicating falling consumer prices (deflation), a situation that was mirrored in China and the United States in 2009 during the financial and economic crisis. Table 3 provides a complete set of annual rates of change for consumer prices across the G20 members over the period 2002–12. During this period, particularly high price increases were recorded in Turkey and Russia, although both countries recorded much lower inflation in the most recent years. In a majority of these years Argentina experienced inflation rates close to or above 10 %. In 2012, inflation rates among the G20 members ranged from no change (0.0 %) in Japan to 10.0 % in Argentina and 10.4 % in India, with the 2.6 % inflation rate for the EU towards the lower end of this scale.

Overnight interbank interest rates varied greatly between the G20 members in 2012, but to a somewhat lesser extent than they had done 10 years earlier. Rates were close to zero in the euro area, Japan, the United States and the United Kingdom in 2012, but reached a high of 9.0 % in India. In nearly all G20 members interest rates were lower in 2012 than they had been in 2002, with the exceptions of Japan where the interest rate rose marginally (but remained close to zero), China where the interest rate rose 0.6 percentage points to 3.3 % and India where the interest rate rose from 6.3 % to 9.0 % (all of the increase in India occurred in 2012).

Among the countries shown in Table 5, the pesos in Argentina and Mexico devalued the most between 2002 and 2012 relative to the euro. By contrast, the Australian and Canadian dollars, Japanese yen and Brazilian real appreciated relative to the euro during this 10-year period.

Data sources and availability

The statistical data in this article were extracted during February 2014. The indicators are often compiled according to international — sometimes global — standards, for example, UN standards for national accounts and the IMF’s standards for balance of payments statistics. Although most data are based on international concepts and definitions there may be certain discrepancies in the methods used to compile the data.

EU and euro area data

Most if not all of the indicators presented for the EU and the euro area have been drawn from Eurobase, Eurostat’s online database. Eurobase is updated regularly, so there may be differences between data appearing in this publication and data that is subsequently downloaded.

G20 countries from the rest of the world

For the 15 G20 countries that are not members of the EU, the data presented have generally been extracted from a range of international sources, most notably the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the United Nations Statistics Division, as well as the OECD. For some of the indicators shown a range of international statistical sources are available, each with their own policies and practices concerning data management (for example, concerning data validation, correction of errors, estimation of missing data, and frequency of updating). In general, attempts have been made to use only one source for each indicator in order to provide a comparable analysis between the countries.

Context

An analysis of the economic situation can be performed using a wide range of statistics, covering areas such as national accounts, government finance, exchange rates and interest rates, consumer prices, and the balance of payments. These indicators are also used in the design, implementation and monitoring of economic policies and have been particularly under the spotlight with respect to the financial and economic crisis.

Gross domestic product (GDP) is the most commonly used economic indicator; it provides a measure of the size of an economy, corresponding to the monetary value of all production activities. GDP includes goods and services, as well as products from general government and non-profit institutions within the country (‘domestic’ production). Gross national income (GNI) is the sum of gross primary incomes receivable by residents, in other words, GDP less income payable to non-residents plus income receivable from non-residents (‘national’ concept).

GDP per capita is often used as a broad measure of living standards, although there are a number of international statistical initiatives to provide alternative and more inclusive measures. GDP at constant prices is intended to allow comparisons of economic developments over time, as the impact of price developments (inflation) has been removed. Equally, comparisons between countries can be facilitated when indicators are converted from national currencies into a common currency using purchasing power parities (PPP) which reflect price level differences between countries.

See also

Further Eurostat information

Publications

- The EU in the world 2014

- Key figures on the enlargement countries — 2014 edition

- Pocketbook on Euro-Mediterranean statistics — 2013 edition

- The EU in the world 2013

- The European Union and the BRIC countries

- The European Union and the African Union — 2013 edition

- The European Union and the Republic of Korea — 2012

Database

- GDP and main components (nama_gdp)

- GDP and main components - Current prices (nama_gdp_c)

- GDP and main components - volumes (nama_gdp_k)

- National Accounts detailed breakdowns (by industry, by product, by consumption purpose) (nama_brk)

- National accounts aggregates and employment by branch (NACE Rev. 2) (nama_nace2)

- National Accounts by 10 branches - aggregates at current prices (nama_nace10_c)

- National accounts aggregates and employment by branch (NACE Rev. 2) (nama_nace2)

- Balance of payments statistics and International investment positions (bop_q)

- Euro area balance of payments (source ECB) (bop_q_euro)

- European Union balance of payments (bop_q_eu)

- European Union direct investments (bop_fdi)

- EU direct investments - main indicators (bop_fdi_main)

- Exchange rates (ert), see:

- Bilateral exchange rates (ert_bil)

- Euro/ECU exchange rates (ert_bil_eur)

- Euro/ECU exchange rates - annual data (ert_bil_eur_a)

- Euro/ECU exchange rates (ert_bil_eur)

- Annual government finance statistics (gov_a)

- Government revenue, expenditure and main aggregates (gov_a_main)

- Government deficit and debt (gov_dd)

- Government deficit/surplus, debt and associated data (gov_dd_edpt1)

- HICP (2005 = 100) - annual data (average index and rate of change) (prc_hicp_aind)

Dedicated section

- Balance of payments

- Exchange rates

- GDP and beyond

- Government finance statistics

- Harmonized Indices of Consumer Prices (HICP)

- Interest rates

- National accounts (including GDP)

Source data for tables and figures (MS Excel)

External links

- International Monetary Fund IMF

- OECD

- United Nations Statistics Division

- World Bank