Archive:Fertility statistics in relation to economy, parity, education and migration

- Data from March 2013. Most recent data: Further Eurostat information, Main tables and Database.

The relationship between the economy and population dynamics has long been discussed, but is still controversial. Fertility is commonly assumed to follow the economic cycle, falling in periods of recession and vice-versa, though scientific evidence is still not unanimous on this. This article looks at fertility trends in 31 European countries against selected indicators of economic recession. Fertility rates are also computed for women differentiated by parity, employment status, educational attainment and migrant status, highlighting the impact that the economic crisis may have on specific population groups.

Main statistical findings

In 2008, several European countries entered a period of economic crisis, usually featuring a fall in gross domestic product (GDP). From the start of the recession, the total fertility rate (TFR, see data sources and availability) started to decline across Europe.

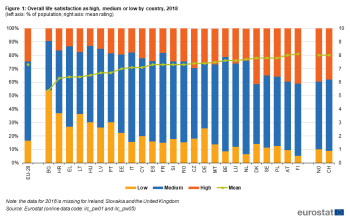

Figure 1 shows that in 31 European countries, the economic crisis spread in 2009, while decreases in fertility became a common feature in Europe with a time lag. The peak of the crisis (in terms of geographic reach) in 2009 was accompanied by stagnation of the TFR in several countries, followed by a distinct fall. In 2008, there were no falls in the rate compared to the previous year, but by 2011, the TFR had declined in 24 countries. With some exceptions, these trends in fertility rates mirrored the changes that occurred in the number of live births.

Fewer births were due more to fewer would-be mothers than to lower fertility

From the beginning of the crisis, the total number of live births in Europe reversed the previous upward trend (see Figure 2). Between 2008 and 2011, the total number of live births fell by 3.5 %, from 5.6 to 5.4 million, and the number of countries which recorded a fall compared to the previous year grew from 1 to 26 out of 31.

The number of live births can be broken down into the product of the age-specific fertility rates by the respective number of women of childbearing age (WCA) — the ‘would-be mothers’. The overall size of this population group has been slowly decreasing over recent years and, by 2011, it was shrinking in about two-thirds of European countries (post-census revisions of the population size in various countries may affect the current estimates — see data sources and availability).

Although the year-on-year change in relative terms of the total number of women of childbearing age is much lower than the corresponding relative changes of the TFR (which is the sum of the agespecific fertility rates), its impact can be more significant. Table 1 reports the total number of live births, which would have occurred under different hypotheses.

Considering that 2008 was the peak year in the number of live births, taking this year as a benchmark and keeping constant its conditions (summarised by the WCA and TFR) over the next three years gives the hypothetical number of live births which would have occurred during 2009-2011 if no change had taken place in both the number of would-be mothers and in age-specific fertility rates. Allowing only the WCA to decrease as actually occurred gives the number of live births resulting from a shrinking number of women of childbearing age who keep their fertility behaviour constant (i.e., the TFR). This hypothetical scenario enables us to roughly estimate the impact of changes in the WCA, all other things being equal. Finally, allowing both WCA and TFR to change leads to what was actually recorded over the period 2009-2011.

Table 1 shows that the change in WCA alone is responsible for about 62 % of the decrease in the number of live births. If fertility had not decreased since 2008, about 189 000 live births would have been ‘lost’ anyway, due to fewer would-be mothers. The decline of the TFR that occurred after 2008 has in fact amplified this effect. This downturn is of most interest because, unlike the changes in WCA, largely determined by past fertility conditions and thus mainly driven by inertia, changes in TFR are supposedly more reactive to current factors.

Fertility rates returned to ‘lowest-low‘ levels in some Eastern European countries

There has been a general recovery of fertility over the past decade (see Table 2), though with some exceptions (such as Luxembourg and Portugal). The average across countries has risen by about 0.15 live births per woman between 2002 and 2008-09. Such an increase in fertility rates is usually explained by scholars as due to recuperation after the postponement of childbearing. Therefore, it would not be an effective increase of the quantum of fertility, but simply a tempo effect. In other words, taking a longitudinal perspective, by the end of their childbearing years, successive cohorts of women would have accomplished about the same level of completed fertility. Decreases recorded by a period indicator such the TFR would be due mainly to temporary postponements of childbearing.

In 2008, no country had a TFR below 1.3, considered by some scholars as marking a level of ‘lowest-low’ fertility. This recuperation process seems to have stopped around 2009 and, by 2011, the TFR in a few countries (Hungary, Poland and Romania) had perhaps unexpectedly fallen again, below the 1.3 live births per woman.

Figure 3 shows the geographic pattern of the TFR over time. At the start of the previous decade, the average TFR was at its lowest over the 12 years considered. In several countries in Northern and Western Europe, its level was above 1.7, while in Eastern and Southern Europe, low fertility was widespread. The next three years see a clear divide between Northern and Western Europe, with a relatively high level of fertility, Eastern Europe, with ‘lowest-low’ fertility, and Central and Southern Europe, with slightly higher fertility, but still below 1.5 live births per woman. Between 2006 and 2008, fertility in Eastern Europe continued to recover, leaving behind only Slovakia: in this period, fertility in Europe is essentially divided by a diagonal running from North-East to South-West. Finally, during the last three years, the average TFR grew further in some countries, but fell back in others, blurring the geographical pattern of low fertility in Eastern Europe.

Changes in fertility partially follow changes in the economy, with an average lag of less than two years

It may be difficult to disentangle what could be a ‘natural’ decrease in the number of live births, due to the shrinking number of women of childbearing age and/or to the continuing decline in their fertility rates, from the impact of an occasional shock, such as an economic crisis. A recession can influence fertility in various ways, although its effect may be softened by government interventions. Apart from the direct impact of the crisis at individual level, the economic uncertainty that can spread in periods of hardship may influence fertility. From this point of view, the duration of a crisis may play an important role and, in some countries, the duration and the depth of the current recession are unprecedented.

Table 3 reports the correlations between the time series of the changes in the TFR and in selected indicators of economic crisis for each European country. In fact, the interest here is in looking at the potential link between changes in economic conditions and changes in fertility behaviour. These correlations have been computed taking into account a lag in the TFR from 0 to 3 years: hence, four correlations were computed for each country and indicator. Table 3 only shows the highest values of the correlations (with the expected sign), together with the lag at which they were found. To focus on the effect of the economic crisis, the correlations were computed using annual data from 2000 to 2011, which makes the number of available cases rather limited, especially for correlations between time series shifted by 3 years. Results also depend on the quality of the demographic data, which may be affected by various issues (see data sources and availability).

The usual indicator of economic growth is based on the GDP. The expected relationship is that negative changes in GDP correspond to negative changes in the TFR, possibly with some delay, thus showing a high positive correlation at particular lags. The correlation with the TFR is relevant in Spain and Latvia without any lag; in Bulgaria, Poland and Romania with one year of lag; and in the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Greece, the Netherlands, Finland, Sweden, Iceland, Norway and Croatia with two years of lag. Taking the overall average across countries, a change in GDP is mostly positively correlated with a change in the TFR within about 19 months.

It must be noted that in some countries, there may also be negative correlations at some lags, thus supporting the hypothesis of TFR changes counter-cyclical to the economic trends, but usually their intensity is lower than the positive correlations at different lags. Exceptions in this regard are Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Austria and Romania. For Malta, Austria and Romania, these negative correlations do not seem to be relevant once the number of available cases is taken into account, whereas they are noticeable for Lithuania at lag 2 and for Latvia at lag 3. In these two countries, the evidence would suggest changes in TFR negatively correlated with changes in GDP.

Another indicator selected for this study is Actual Individual Consumption (AIC), which is considered to provide a better measure of the material welfare condition of households, because it refers to goods and services actually consumed by individuals, irrespective of whether these goods and services are purchased and paid for by households, by government, or by non-profit organisations. By looking at the correlation of the changes in AIC with changes in TFR, the intention is to analyse the impact of the changing material situation of households, rather than the country’s living standards (as measured by the GDP), on fertility behaviour. Likewise for GDP, the expected relationship between changes in AIC and TFR is positive.

Most relevant positive correlations between AIC and lagged TFR are found for Belgium, Denmark, Malta and Poland at lag zero; for Bulgaria, Greece, Latvia and Romania with a lag of one year; for Estonia, the Netherlands and Norway with a lag of two years; and for Hungary, Sweden, the United Kingdom and Switzerland with a lag of three years. The average lag (without Spain and Iceland) for a change in TFR is thus again of about 19 months. However, in Germany, Cyprus, Luxembourg and Austria, there is a negative correlation higher in absolute values than the positive one, but still at negligible levels, whereas in Latvia and Lithuania, this negative correlation is rather noticeable.

The next indicator is the annual unemployment rate for the age group 15-49 (UNE). The expected relationship here is with negative sign, meaning that a positive change of the UNE should be correlated with a negative change of the (lagged) TFR. This is particularly the case for Greece and Latvia without lag; for Poland with one year of lag; for Denmark, Estonia, Cyprus, the Netherlands and Iceland with two years of lag; and for the United Kingdom with three years of lag. The country where there is a positive correlation higher than the negative are Belgium, the Czech Republic, France, Lithuania, Portugal and Slovenia, but none relevant. On average, changes in the unemployment rate would then be negatively correlated with changes in TFR lagged by about 19 months, as in the case of GDP and AIC.

The last indicator used for Table 3 is the annual average of the consumers’ confidence index (CCI), meant to measure the sentiment of economic uncertainty. As for GDP and AIC, the correlation between changes in the CCI and lagged changes in the TFR is expected to be positive. The values are particularly relevant only for Latvia and Romania, with one year of lag, and for Poland with two years of lag. However, several countries have negative correlations higher in absolute value than the highest positive: Belgium, Austria, Slovakia, Finland, Sweden, and particularly Spain, Lithuania and Luxembourg. Privileging the pro-cyclical relationship between CCI and TFR, on average, a change in consumers’ confidence would be correlated with a change in the TFR, delayed by about 22 months.

In general, the correlations of economic indicators with the lagged TFR have the expected sign in most countries, though not particularly significant. However, in a few cases, it cannot be excluded that the economic crisis may actually open a ‘window of opportunity’ for childbearing, especially for specific population groups.

Slight tendency to wider decreases in first births than in subsequent births

An economic crisis may prompt would-be parents to postpone childbearing, especially if they are childless. Table 4 shows the quota of the TFR attributable to live births from (previously) childless women (TFR 1) and that for women who already had at least one child (TFR 2+). Due to data unavailability, these indicators could not be computed making reference to the population composition by parity (the number of live births a woman had in the past). Thus the female population ‘exposed’ to childbearing is the total number of women of childbearing age, regardless of any previous live birth they may have delivered. By multiplying the percentages in Table 4 with the corresponding TFR value in Table 2, the values of TFR 1 and TFR 2+ (not shown here) can be obtained.

In general, the decrease from the respective peak value over 2007-2011 was slightly more relevant for the first-order TFR. However, on the whole, the two rates mostly moved together, so by 2011, the difference between them did not increase much. A particular case is Greece, where the TFR of order two and higher has plummeted over recent years, falling below the TFR of first order, which rose slightly.

In proportion to the overall TFR, in Bulgaria, Estonia, Spain, Latvia and Lithuania, the decrease in the TFR 1 from the peak value over the four years to 2011 is higher than 3 percentage points (p.p.), and in Ireland and in the Nordic countries the decrease is between 1 and 3 p.p.

A few countries saw the proportion of TFR attributable to childless women rise, as in Greece and Slovakia. On average across all countries, there was a slight reduction over time of the proportion of TFR attributable to first-order live births. This means that the changes in TFR 1 were either somewhat less positive or more negative than those of TFR 2, or even trended in the opposite (negative) direction.

Mixed fertility behaviour across countries for employed and non-employed women

Because the economic crisis may have differing effects on the fertility behaviour of different categories of women, it is interesting to look at values for the specific fertility indicator for selected population breakdowns.

Table 5 shows the specific TFR for employed and non-employed women, the latter comprising unemployed and inactive women. Across countries, the differential fertility according to employment status is not consistently positive or negative between 2007 and 2011. In Belgium, Germany, Austria, Romania, Finland and Norway, nonemployed women have higher fertility than those employed; the opposite applies for the other countries for which data are available, except for Greece, Luxembourg and Malta, where the group with higher fertility changes over time.

Differentials in fertility by employment status can reach remarkable values in both directions: in Germany, in 2011, employed women have 1.8 live births fewer than non-employed women, about the same value as in Croatia, where the differential is reversed.

The tendency of fertility in the two groups over recent years is not consistent across Europe. In some countries, the differentials have further increased; in other countries, specific TFR have been converging, sometimes even reversing the sign of the differential.

For instance, in Germany, the fertility of nonemployed women has increased and that of employed women decreased, while in Spain, the opposite occurred; in Greece, the TFR of nonemployed women fell below that of employed women, changing from a positive differential of about 0.2 average live births for non-employed women to a similar value for employed women; in Norway, the two groups converged.

It is thus difficult to detect a common pattern across Europe, taking into account that fertility behaviour in population groups defined according to their relationship to the labour market may be influenced by national policies to combine work and family life.

As total TFR also depends also on the composition of the population (see methodological notes), an increase or decrease in a specific TFR does not necessarily impact much on the overall TFR.

For instance, in Germany, the proportion of women of childbearing age classified as non-employed is slightly above one third. Hence, the relatively high fertility of this population group influences the overall TFR much less than that of employed women of childbearing age, whose fertility is even below one live birth per (employed) woman. In fact, the increase of 0.46 live births per nonemployed woman over the five years examined has produced little effect on the total TFR, which has continued to be around 1.37 live births per woman (see Table 2), due to the corresponding fall of about 0.10 live births in the TFR of employed women.

Fertility of women with medium education has decreased more visibly than of those with low or high education

The level of educational attainment is often considered to be a proxy of the socio-economic status of a person. To improve comparability across countries, the national level of educational attainment is converted according to an international standard classification of education (ISCED) with seven degrees from 0 to 6. The level zero indicates no formal education and the level 6 corresponds to the highest achievable level of education (such as a PhD).

Table 6 shows the specific TFR of women with different levels of educational attainment, grouped in ‘low’ (ISCED from level 0 to level 2), ‘medium’ (ISCED 3-4) and ‘high’ (ISCED 5-6).

Apart from Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland and Norway), Portugal and Malta, in general, women with low education had a higher TFR between 2007 and 2011. Differentials reached a level as high as 2.2 live births per woman (Slovakia, 2009).

Comparing 2011 to the peak year of fertility (in bold in Table 6), on average across countries, the fertility of women with a medium level of education dropped by about 9 %, while the decrease for women with high or low education was less significant. However, the pattern at national level is quite diversified, and the same applies within countries. Fertility may have different patterns in different population groups.

Changes in the specific TFR of population subgroups affect the overall TFR to the extent of their relative weight in the population. So, in general, the same change would have less effect if it were to occur in the fertility of women with high education, given that their share in the total number of women in childbearing ages is about one fifth (on average across countries).

In most countries, immigrants’ fertility decreased more than that of natives

Citizenship and country of birth are two different ways of looking at migrant status. In general, a foreign-born person has migrated at least once in their lifetime, while a person with foreign citizenship has not necessarily done so, but has a foreign background.

These characteristics may influence the demographic behaviour in terms of fertility, though in neither case is there a direct indication of the duration of the residence of the person in the host country.

A foreign-born woman could actually have arrived in a country long ago, or even have grown up there, hence being largely influenced by the local culture. A woman with foreign citizenship may acquire the citizenship of the host country — the longer her residence in the host country, the higher the probability that she would change her citizenship, thus possibly leaving the group of women with foreign citizenship (with differences depending on the policies of naturalisation of the country).

Data sources and availability

<description of data sources, survey and data availability (completeness, recency) and limitations>

Context

<context of data collection and statistical results: policy background, uses of data, …>

Further Eurostat information

Publications

Main tables

- Title(s) of second level folder (if any)

- Title(s) of third level folder (if any)

Database

- Title(s) of second level folder (if any)

- Title(s) of third level folder (if any)

Dedicated section

Methodology / Metadata

<link to ESMS file, methodological publications, survey manuals, etc.>

- Name of the destination ESMS metadata file (ESMS metadata file - ESMS code, e.g. bop_fats_esms)

- Title of the publication

Source data for tables, figures and maps (MS Excel)

Other information

<Regulations and other legal texts, communications from the Commission, administrative notes, Policy documents, …>

- Regulation 1737/2005 (generating url [http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:32005R1737:EN:NOT Regulation 1737/2005]) of DD Month YYYY on ...

- Directive 2003/86/EC (generating url [http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:32003L0086:EN:NOT Directive 2003/86/EC]) of DD Month YYYY on ...

- Commission Decision 2003/86/EC (generating url [http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:32003D0086:EN:NOT Commission Decision 2003/86/EC]) of DD Month YYYY on ...

<For other documents such as Commission Proposals or Reports, see EUR-Lex search by natural number>

<For linking to database table, otherwise remove: {{{title}}} ({{{code}}})>

External links

See also

Notes

[[Category:<Under construction>|Name of the statistical article]]

[[Category<Subtheme category name(s)>|Name of the statistical article]] [[Category:<Statistical article>|Name of the statistical article]]

Delete [[Category:Model|]] below (and this line as well) before saving!