Archive:Living standard statistics

Living standards, as measured by the median equivalised disposable income, fell in 15 Member States in 2010 compared with a year earlier, after adjusting for inflation. In the vast majority of Member States the median income fell most for the unemployed and least for people in employment. Income decreased in the bottom quintile of the income distribution in most Member States. In 15 Member States, income inequality increased because income in the top quintile decreased less or increased more than in the bottom quintile. When looking at households’ material conditions, in 2011 around 10 % of the EU population reported that they could not afford a meal with meat, chicken, fish or a vegetarian equivalent every second day. This represents an increase of 1 percentage point (pp) compared with 2010. All figures are based on the latest EU-SILC (Statistics on Income and Living Conditions) data collected in 2011.

Main statistical findings

Household disposable income corresponds to income from market sources and cash benefits after deduction of direct taxes and regular interhousehold cash transfers. It can be considered as the income available to the household for spending or saving. The living standards achievable by a household with a given disposable income depend on how many people and of what age live in the household.

Household income is thus ‘equivalised’ i.e. adjusted for household size and composition so that the incomes of all households can be looked at on a comparable basis. Equivalised disposable income is an indicator of the economic resources available to a standardised household. For a lone-person household it is equal to household income. For a household comprising more than one person, it is an indicator of the household income that would be needed by a lone person household to enjoy the same level of economic wellbeing. This income concept, based on the assumption of income sharing within the household, and of economies of scale resulting from living together, is used in this article.

The latest data, collected during 2011, include income for the reference period 1 January –31 December 2010 and non-income variables referring to 2011.2

The median is the income value which divides a population, when ranked by income, into two equal-sized groups: exactly 50 % of people fall below that value and 50 % are above it. When analysing income, this is the measure most commonly used to represent average income because the highly skewed nature of the income distribution can lead to the very high incomes of a few having a disproportionate impact on the mean. Poverty thresholds are calculated on the basis of the median equivalised disposable income.

Median equivalised disposable income in national currencies fell in eight Member States in nominal terms (without adjusting for inflation) in 2010 compared with a year earlier (Table 1).

The sharpest drops occurred in Greece, where median income fell by 8.2 %, Latvia (-7.2 %) and Spain (-4.0 %). It increased the most in Poland (+5.3 %), Hungary (+5.1 %) and Malta (+4.7 %).

However, nominal changes do not tell the whole story about income changes as inflation should also be considered.

Median incomes have thus been adjusted by the annual rate of change in the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) for 2010 to obtain real changes.

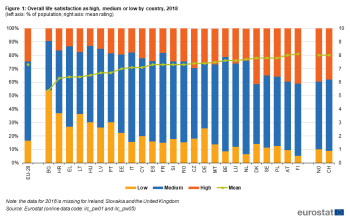

After adjusting for inflation, median equivalised disposable income in national currencies fell in 15 Member States in 2010 compared with a year earlier (Table 1 and Figure 1).

The sharpest drop in real terms occurred in Greece, where the median equivalised disposable income fell by 12.3 %. It fell by 6.6 % in Bulgaria, 6.1 % in Latvia, 5.8 % in Spain, 4.8 % in Estonia and 4.4 % in Portugal. A sharp decrease of 9.7 % was also registered in Iceland. Median income stagnated or increased in real terms by less than 1 % in Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Hungary, Slovenia, Finland and Sweden, while it increased by more than 1 % in Malta (+2.6 %), Poland (+2.5 %), Slovakia (+2.4 %) and Austria (+1.7 %).

Increases or decreases in median income can essentially be explained by changes in family situation, employment situation, the welfare system and taxes.

Median income fell most for the unemployed

The activity status presented in the analysis is self-declared as measured by EU-SILC. Data are presented for persons who declared their main activity status as being: employees, employed persons other than employees (e.g. selfemployed), retired and unemployed.

The median equivalised disposable income for a specific category of persons has to be regarded in the household context as it is influenced also by the income of other persons in the household.

In the vast majority of Member States median equivalised disposable income fell in real terms most for the unemployed in 2010 compared with 2009 (Table 2).

Only in Denmark, Germany, France, Cyprus, the Netherlands, Finland and the United Kingdom was the income change of the unemployed better than for employees or the self-employed.

Median income for the unemployed fell by 15.2 % in Greece, 12.2 % in Bulgaria, 12.0 % in Estonia, 8.9 % in Italy, 8.8 % in Spain and 8.7 % in Latvia. It grew by 5.8 % in Denmark, 4.3 % in Poland, 4.2 % in Finland and 4.1 % in Germany.

The fall in median income for the unemployed can partly be explained by the rise in long-term unemployment and by the fact that in most countries the unemployed have access to unemployment benefits only for a limited time. Changes in the benefit system in some countries could also be part of the explanation.

In some countries other categories faced the sharpest income fall. In Luxembourg and the Netherlands median income fell most for employees, by 4.3 % and 1.5 % respectively. In Poland it increased for employees (+0.9 %) but less than for other categories.

Income fell most for employed persons other than employees in France (-11.1 %), Romania (-10.6 %), Portugal (-9.0 %), Cyprus (-5.2 %), the United Kingdom (- 3.6 %) and Slovenia (-2.7 %).

The income change for retired people was smaller than for other categories only in Denmark (+1.1 %), Germany (+0.2 %), Lithuania (-7.1 %), Finland (+0.3 %) and Sweden (-2.6 %).

Income fell most in the bottom income quintile in most Member States

Median equivalised disposable income does not give a complete picture of changes across the income distribution.

Table 3 shows the change in real terms between 2009 and 2010 of equivalised disposable income for the first and fifth quintiles of the income distribution. As a basis for calculations, the median of the interval covered by each quintile is used. This is a measure of the average situation in each quintile.

Income decreased from 2009 to 2010 in the bottom quintile in 18 Member States after adjusting for inflation. The sharpest fall occurred in Greece, where the median income of this quintile decreased by 17.3 %, in Estonia (-11.4 %) and in Bulgaria (-10.2 %). It increased the most in Lithuania (+3.5 %), Luxembourg and Poland (both +2.9 %).

For the top quintile income also decreased in 18 Member States but with different patterns and intensity. The sharpest fall occurred in Lithuania, where the median of this quintile decreased by 12.4 %, in Greece (-11.1 %) and in Latvia (-7.4 %). It increased the most in Hungary (+9.1 %), Denmark (+4.3 %) and Finland (+2.5 %).

All in all, income inequality is rising in 15 Member States, because income in the fifth quintile decreased less or increased more than in the first quintile.

In order to explore in greater depth the effects of income changes on income inequalities we need to gain a better understanding of the income dynamics in different parts of the income distribution. For this purpose we divided countries into groups sharing similar characteristics in terms of changes in income in the five quintiles between 2009 and 2010.

In the first group presented in Figure 2 and composed of Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Greece, Spain, Hungary, Portugal, Romania, Finland and Sweden, income decreased most in the lower quintiles and decreased less (or increased) in the upper quintiles, thereby contributing to an increase in income inequality. This pattern is particularly clear (i.e. systematic over all quintiles) in Bulgaria, Greece and Hungary.

In the second group in Figure 3, composed of Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, the United Kingdom, Iceland, Norway and Croatia, income decreased most (or increased least) for the highest quintiles and decreased least (or increased most) in the lower quintiles, thereby contributing to a decrease in income inequality. This is particularly visible in Lithuania and Iceland.

However, for the other countries there was no clear trend along the income distribution and mixed effects on income inequality were registered.

Around 10 % of EU citizens cannot afford a meal with meat, chicken, fish or a vegetarian equivalent every second day

Material deprivation complements the income perspective by providing an estimate of the proportion of people whose living conditions are severely affected by a lack of resources.

Among material deprivation items, the inability to afford a meal with meat, chicken, fish or a vegetarian equivalent every second day showed the greatest change in 2011 at EU-27 level compared with 2010. The change in Member States of this deprivation item is also in some cases correlated with the decrease in income in the lowest quintiles.

In 2011 9.7 % of the EU population reported that they could not afford this item. This represents an increase of 1 pp compared with 2010.

There is considerable variation among Member States. The percentage of people reporting this deprivation item ranged from 3 % or less in Spain, the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden and Luxembourg to 29 % in Hungary, 30.8 % in Latvia and a maximum of 50.8 % in Bulgaria in 2011.

Compared with 2010, the percentage of people reporting that they could not afford such a meal every second day increased by 7.6 pp in Bulgaria, 5.7 pp in Italy and 4.0 pp in Latvia.

At the same time it fell by more than 1 pp only in Poland (-1.4 pp) and in Austria (-1.5 pp).

Data sources and availability

<description of data sources, survey and data availability (completeness, recency) and limitations>

Context

<context of data collection and statistical results: policy background, uses of data, …>

Further Eurostat information

Publications

Main tables

- Title(s) of second level folder (if any)

- Title(s) of third level folder (if any)

Database

- Title(s) of second level folder (if any)

- Title(s) of third level folder (if any)

Dedicated section

Methodology / Metadata

<link to ESMS file, methodological publications, survey manuals, etc.>

- Name of the destination ESMS metadata file (ESMS metadata file - ESMS code, e.g. bop_fats_esms)

- Title of the publication

Source data for tables, figures and maps (MS Excel)

Other information

<Regulations and other legal texts, communications from the Commission, administrative notes, Policy documents, …>

- Regulation 1737/2005 (generating url [http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:32005R1737:EN:NOT Regulation 1737/2005]) of DD Month YYYY on ...

- Directive 2003/86/EC (generating url [http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:32003L0086:EN:NOT Directive 2003/86/EC]) of DD Month YYYY on ...

- Commission Decision 2003/86/EC (generating url [http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:32003D0086:EN:NOT Commission Decision 2003/86/EC]) of DD Month YYYY on ...

<For other documents such as Commission Proposals or Reports, see EUR-Lex search by natural number>

<For linking to database table, otherwise remove: {{{title}}} ({{{code}}})>

External links

See also

Notes

[[Category:<Under construction>|Name of the statistical article]]

[[Category<Subtheme category name(s)>|Name of the statistical article]] [[Category:<Statistical article>|Name of the statistical article]]

Delete [[Category:Model|]] below (and this line as well) before saving!