Archive:Statistics on income and living conditions by degree of urbanisation

This Statistics Explained article is outdated and has been archived - for recent articles on this topic see here.

- Data from February 2013. Most recent data: Further Eurostat information, Main tables and Database.

European Union (EU) policies aim to substantially reduce the number of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion, thereby creating a more inclusive society. This article looks at a range of income and living conditions indicators: the analysis is presented according to different levels of population density, covering seven indicators that are used to monitor social inclusion and social protection. It is based on a classification of regions according to their degree of urbanisation, determined by their population density and total population; this results in three unique area types — densely populated (urban) areas, intermediate density areas and thinly populated (rural) areas.

(%) - Source: Eurostat (ilc_peps13)

(%) - Source: Eurostat (ilc_mddd23)

(%, persons aged 0–59) - Source: Eurostat (ilc_lvhl23)

(%) - Source: Eurostat (ilc_lvho07d)

(%) - Source: Eurostat (ilc_mdho06d)

Main statistical findings

People at risk of poverty or social exclusion

The number of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion is a headline indicator used to measure progress in meeting the goals of the Europe 2020 strategy, namely to have at least 20 million fewer people at risk of poverty or social exclusion by 2020. The indicator is a Boolean combination of three sub-indicators: the at-risk-of-poverty rate, the severe material deprivation rate, and the share of people living in households with very low work intensity. A person is described as being at risk of poverty or social exclusion if he/she satisfies the criteria for at least one of these sub-indicators. The first sub-indicator — the at-risk-of-poverty rate — is a relative poverty indicator, as it measures the share of the population with an income that is less than 60 % of national median disposable income. As a result, someone who is below the poverty line in Luxembourg (a country with a high median income) may not be considered as being at risk of poverty if he/she was living in Bulgaria (where the poverty line is based on a much lower level of median income) and receiving the same income. The second indicator is an absolute measure of poverty, as it measures — in the same way across all EU Member States — the proportion of the population who cannot afford at least four out of a list of nine items that are considered as being essential for everyday living (see the section on data sources and availability for the full list and more information). The third indicator measures exclusion from the labour market: the work intensity of a household is defined as the ratio of the months worked by working-age household members compared with the theoretical number of months that could have been worked in the same period (if all working-age household members had worked full-time); any household with a ratio below 0.2 is considered as being a household with very low work intensity.

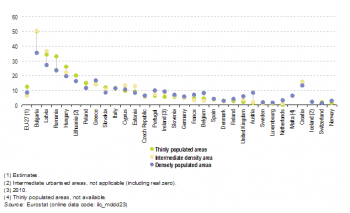

In 2011, some 24.2 % of the EU-27 population — or 119.6 million persons — were estimated to be at risk of poverty or social exclusion. This ratio peaked at 29.3 % of the population in thinly populated areas of the EU, with a rate that was considerably higher than those recorded for either densely populated areas (23.3 %) or intermediate density areas (21.0 %). These differences (by degree of urbanisation) suggest that the at-risk-of-poverty rate has a strong geographical dimension (in other words, a location effect) and that the differences in the ratios observed do not exclusively depend on personal characteristics such as education, employment status, household type and age.

In some of the most economically developed EU Member States — for example, Belgium, the United Kingdom, Austria, France, Malta, Luxembourg, Sweden and the Netherlands — densely populated areas were less inclusive, as they recorded the highest proportion of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion (when compared with intermediate density and thinly populated areas in the same country); the same was true in Iceland.

By contrast, in 19 of the EU Member States, principally those that joined the EU in 2004 or 2007 (excluding Malta), but also Spain, Greece, Ireland (data for 2010), Italy, Portugal, Germany, Denmark and Finland, thinly populated areas accounted for the highest proportion of people who were at risk of poverty or social exclusion. The proportion of people living in intermediate density areas who were at risk of poverty or social exclusion was always lower than in at least one of the other area types. Intermediate density areas recorded the lowest risk of poverty or social exclusion in nine of the Member States: Belgium, Denmark, Germany, France, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, Austria and Sweden. The presence of some of the largest Member States within this list (principally Germany, France and Italy) explains, to a large extent, why intermediate density areas had the lowest risk of poverty or social exclusion across the whole of the EU-27.

The highest risk of poverty or social exclusion within densely populated areas was recorded in Bulgaria (38.6 %), despite this being by far the lowest proportion of people at risk in Bulgaria for the three types of area (that are detailed in Figure 1). Indeed, Bulgaria recorded the highest risk of poverty or social exclusion for each of the three degrees of urbanisation, 54.7 % for intermediate density areas and 57.7 % for thinly populated areas. Bulgaria also recorded the widest range between at-risk-of-poverty or social exclusion rates for the three different degrees of urbanisation (a difference of 19.1 percentage points between thinly and densely populated areas). There were also considerable differences between the rates reported across Romania (19.0 percentage points), while relatively large gaps (10.0 percentage points or more) were also evident in Lithuania, Spain, Poland and Hungary — where the highest risk of poverty or social exclusion was consistently recorded for thinly populated areas and the lowest risk was registered in densely populated areas. By contrast, the risk of poverty or social exclusion was 11.4 percentage points higher in the densely populated areas of Austria than it was in intermediate density areas, for which the lowest proportion of the population was at risk according to this indicator. A similar pattern was observed in Belgium, with a difference of 10.1 percentage points between the high for densely populated areas and the low for intermediate density areas.

The risk of poverty or social exclusion, as a function of the degree of urbanisation, did not vary greatly in the three EFTA countries for which data are available (Iceland, Norway and Switzerland). The largest difference in the risk of poverty or social exclusion was recorded in Switzerland, where thinly populated areas recorded a rate that was 4.5 percentage points higher than for intermediate density areas.

The range was wider in Croatia, where thinly populated areas recorded the highest risk of poverty or social exclusion (38.1 %), which was 11.1 percentage points more than in densely populated areas.

People at risk of poverty

Figure 2 presents a similar analysis (to that of Figure 1) but focuses on the at-risk-of-poverty rate, which was estimated to be 16.9 % for the EU-27 population in 2011. In other words, there were 83.6 million persons in the EU-27 who were at risk of poverty. The highest proportion of persons who were at risk of poverty was recorded for those living in thinly populated areas (21.1 %). This was 5.4 percentage points higher than the corresponding share for densely populated areas, which, in turn, was 0.6 percentage points higher than for intermediate density areas.

It is important to note that the at-risk-of-poverty rate reflects low levels of income in comparison with other residents of the same country. Furthermore, it does not take into account differences in the cost of living within and between different countries. With this in mind, Bulgaria recorded the highest proportion of its population — among the EU Member States — being at risk of poverty for both thinly populated areas (31.8 %) and intermediate density areas (25.5 %). However, the highest shares of the population at risk of poverty in densely populated areas were recorded in Italy (18.9 %) and Belgium (18.8 %). Those living in urban, densely populated areas in Belgium, the United Kingdom, Luxembourg, Austria, France, Sweden, Malta and the Netherlands faced a higher risk of poverty than those living in either intermediate or thinly populated areas — thereby supporting the premise that some of the most economically developed EU Member States recorded a higher risk of poverty within their urban, densely populated areas, while the majority of the EU Member States that joined the EU in 2004 or 2007 (with the notable exception of Malta) were characterised as having a higher risk of poverty in their thinly populated, rural areas.

While the risk of poverty tended to be higher within the thinly populated areas of those Member States that joined the EU in 2004 or 2007, these countries were also characterised as having a larger difference between at-risk-of-poverty rates in the three different types of area. The widest range was recorded in Romania, where 31.2 % of those living in thinly populated areas were at risk of poverty, compared with only 7.0 % in densely populated areas — in other words, the rate in thinly populated areas was around 4.5 times as high as that in densely populated areas. However, given the at-risk-of-poverty rate is not adjusted for differences in cost of living between the different types of area, this figure may be overestimated. There were also quite large absolute differences between the rates recorded in the three different types of area in Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, Lithuania, Spain and Latvia. Generally these differences were recorded (as for Romania) on the basis of a comparison between highs for thinly populated areas and lows for densely populated areas — the only exception was Latvia, where the lowest at-risk-of-poverty rate was recorded for intermediate density areas.

Severe material deprivation rate

Figure 3 shows an analysis of the severe material deprivation rate by degree of urbanisation in 2011. The highest proportion of persons facing severe material deprivation was recorded in thinly populated areas of the EU-27 (12.3 %), while the rates for densely populated areas (8.4 %) and intermediate density areas (6.2 %) were considerably lower. There were 16 Member States where severe material deprivation affected less than 10 % of the population, irrespective of the type of area they lived in. Among these, there was a tendency for urban regions to record the highest proportion of persons facing severe material deprivation; this was most notably the case in Austria and Belgium. The Czech Republic and Denmark were the only Member States (where severe material deprivation affected less than 10 % of the population) to report that thinly populated areas had a higher proportion of persons facing severe material deprivation.

There were seven Member States where the share of the population facing severe material deprivation was between 10 % and 20 %. At the upper end of the range, at least 20 % of the total population was affected by severe material deprivation in Bulgaria, Latvia, Romania and Hungary. Within these four countries, this phenomenon was most prevalent in either thinly populated or intermediate areas. Around half of the population living in thinly populated and intermediate areas in Bulgaria faced severe material deprivation. In Latvia the share was just over one third for both thinly populated and intermediate areas, while a similar proportion (just under a third) of the population living in thinly populated areas of Romania also faced this type of deprivation. In Hungary, the highest share was recorded for those living in thinly populated areas, where just over a quarter of the population was facing severe material deprivation.

People living in households with very low work intensity

Figure 4 provides information in relation to the share of people living in households with very low work intensity, in other words, those households that are, to a high extent, excluded from the labour market. Across the EU-27 in 2011, an estimated 1 in 10 (10.0 %) of the population aged 0–59 were living in households with very low work intensity. An analysis by degree of urbanisation suggests that densely populated areas in the EU-27 recorded the highest proportion of the population aged 0–59 living in households with very low work intensity (11.0 %). By contrast, about 9.3 % of people from thinly populated areas were living in households with very low work intensity, which was 0.4 percentage points higher than the corresponding share for those living in intermediate density areas.

The pattern experienced within the EU-27 resulted from a higher than average share of households with very low work intensity among those living in the densely populated areas of Belgium, Austria, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Malta, Sweden, the United Kingdom and Greece. The contribution of these Member States outweighed the reverse situation, whereby the risk of very low work intensity was higher in thinly populated or intermediate areas — this was often the situation in many of the Member States that joined the EU in either 2004 or 2007. Indeed, in this latter group of countries, the highest proportion of people living in households with very low work intensity was often recorded for thinly populated areas, for example, in Bulgaria, Lithuania, Hungary and Slovakia, as well as in Croatia. The proportion of people living in households with very low work intensity in these countries was at least 3.0 percentage points higher for thinly populated areas than for either of the other two area types. The same was true, although to a lesser degree (no more than 1.3 percentage points difference), in Estonia, Cyprus, Denmark, Italy, Latvia and Poland.

In Romania, Spain, Ireland (data for 2010) and Finland, those living in intermediate density areas faced the greatest risk of being in a household with very low work intensity. Almost one in four (24.2 %) persons aged 0–59 in intermediate density areas in Ireland were living in a household with very low work intensity, while the corresponding proportions for people living in densely populated and thinly populated areas were also exceptionally high, at more than 20.0 %. By contrast, although 22.0 % of those living in intermediate density areas in Romania were living in a household with very low work intensity in 2011, this was at least three times as high as for those living in either thinly or densely populated areas.

Overcrowded households

The proportion of people living in an overcrowded household stood at an estimated 17.1 % within the EU-27 in 2011. An analysis by degree of urbanisation shows that the highest share was recorded for thinly populated areas, where in excess of one in four (22.1 %) persons faced overcrowding. This was considerably higher than the corresponding shares recorded for those living in densely populated areas (17.8 %) and especially for those living in intermediate density areas (11.3 %). Figure 5 shows that a high proportion of persons lived in overcrowded households (irrespective of the degree of urbanisation) in Romania, Poland, Hungary, Latvia, Bulgaria and Slovakia; as well as in Croatia. Among the three types of area, densely populated areas were associated with the highest overcrowding rate across most of the EU Member States. There were only five exceptions, although four of these featured among the six Member States with the highest overcrowding rates. In Romania, Latvia, Hungary and Cyprus those living in intermediate density areas recorded the highest overcrowding rates, while in Poland the highest share was recorded for those living in thinly populated areas.

Overburden of housing costs

Figure 6 presents information on the burden of housing costs. The average share of the EU-27 population that was overburdened by housing costs in 2011 was 11.5 %; this is the share of the population living in households where total housing costs (net of housing allowances) represent more than 40 % of disposable income (net of housing allowances). The share for those living in densely populated areas of the EU-27 was higher, reaching 13.4 %, while the housing cost overburden rate was close to 1 in 10 for both intermediate density areas (10.0 %) and thinly populated areas (9.7 %). In the majority of the EU Member States the proportion of people who were overburdened by housing costs was highest in densely populated areas (which may be linked to higher average house/flat prices and therefore mortgage repayments, as well as rents in urban areas). The exceptions were Hungary, Spain, Latvia, Bulgaria and Malta, where the highest proportion of the population that was overburdened by housing costs was recorded in intermediate density areas, as well as in Romania and Slovakia where the highest rates were recorded in thinly populated areas; this was also the case in Croatia.

The widest range across the three types of area was recorded in Denmark, where those living in densely populated areas were 1.6 times as likely to face the burden of housing costs as in the other two types of area. There were also relatively broad ranges in the Netherlands and in Greece: as a considerably smaller proportion of those living in rural, thinly populated areas reported being overburdened from housing costs; the same pattern was also observed in Switzerland. By contrast, the opposite pattern was recorded in Romania and Slovakia, as well as in Croatia, as the housing cost overburden rate was highest for those living in rural, thinly populated areas.

Severe housing deprivation

A complementary analysis related to housing is shown in Figure 7, which presents information on those facing severe housing deprivation. The severe housing deprivation rate is defined as the percentage of the population living in a dwelling which is considered as overcrowded, while also exhibiting at least one of the housing deprivation measures; the latter is a measure of poor amenities and is calculated by referring to those households with: a leaking roof; no bath/shower and no indoor toilet; or a dwelling that is considered as being too dark.

Just over 1 in 20 persons (5.5 %) in the EU-27 faced severe housing deprivation in 2011. An analysis by degree of urbanisation for the three types of area suggests that severe housing deprivation was most prevalent in thinly populated areas of the EU-27 (8.7 % of this population), while 5.0 % of those living in densely populated areas faced this type of deprivation. The latter figure was 1.5 percentage points above the proportion of people living in intermediate density areas in the EU-27 who were facing severe housing deprivation (3.5 %).

In the majority of the EU Member States there was little variation between severe housing deprivation rates when analysed by degree of urbanisation. However, a considerably higher share (33.0 %) of people living in thinly populated areas of Romania recorded severe housing deprivation than in either densely populated (14.4 %) or intermediate density areas (13.9 %). There was also a wide gap in Latvia, where those living in thinly populated areas were almost 3.5 times as likely as those living in intermediate density areas to state that they faced severe housing deprivation. Thinly populated areas also recorded the highest degree of severe housing deprivation in Hungary, Poland, Lithuania, Greece, Slovakia and Estonia, whereas densely populated areas tended to record the highest severe housing deprivation rates in those countries where the rate remained relatively low overall (mainly EU-15 Member States). Bulgaria, Cyprus and Malta were the only Member States in which intermediate density areas recorded the highest severe housing deprivation rate.

A comparison summarising indicators across the whole of the EU

This final section of analysis attempts to identify similarities/dissimilarities among the seven indicators presented for income and living conditions, depending on rates and shares according to the degree of urbanisation. It looks briefly at the situation for the EU-27 average and then identifies different groups of countries that have similar patterns in relation to the distribution of the seven indicators. It draws some broad conclusions for the EU Member States collectively which differ from the patterns observed for the EU-27 as a whole.

Across the whole of the EU-27 in 2011, thinly populated areas recorded the highest shares or rates for five of the seven income and living conditions indicators presented in this article. As such, thinly populated areas in the EU-27 were generally the type of area that was most vulnerable to the threat of poverty and exclusion. The two exceptions concerned the share of the population living in households with very low work intensity and the share of the population that was overburdened by housing costs — which affected a higher proportion of the population living in densely populated areas. Densely populated areas across the whole of the EU-27 had the second highest shares or rates for the five remaining income and living conditions indicators. Consequently, people living in intermediate areas were the least likely to face the issues summarised by these income and living conditions indicators, as the lowest rates or shares for six out of the seven measures were recorded in this type of area. The only exception was the housing cost overburden rate, where the EU-27 average was higher in intermediate density areas than in thinly populated areas.

In very broad terms it can be concluded that, with the exception of an overburden from housing costs and facing very low work intensity, people in thinly populated areas in the EU-27 were most likely to face the kind of difficulties associated with living conditions and income that are presented in this article, while those in intermediate density areas were the least likely to face these difficulties.

A comparison summarising indicators across the Member States

While this conclusion holds for the EU-27 as a whole a great variety of situations were observed across the individual Member States. Poverty and social exclusion tended to be more prevalent in the thinly populated areas of those Member States that joined the EU in 2004 or 2007 and values in these countries were often considerably higher than for the two other types of area. As such, they had a relatively high impact on the EU-27 average, which tended to conceal the opposite situation in the EU-15 Member States, where poverty, social exclusion and especially housing issues were more prevalent among the population living in densely populated areas.

A comparison summarising all indicators by EU Member State shows that densely populated areas in Belgium, France, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Austria, Sweden and the United Kingdom had the highest shares and ratios for all seven income and living conditions indicators, while these urban areas also ranked first for a majority of the seven indicators in Germany, Ireland (data for 2010), Greece, Portugal, Slovenia and Finland, as well as in Iceland, Norway and Switzerland. By contrast, densely populated areas had the lowest (or joint lowest) values for all seven indicators in Hungary and the lowest values for six of the seven indicators in Bulgaria and Slovakia. As for the EU-27 as a whole, intermediate density areas had the lowest (or joint lowest) values for six of the seven indicators in Denmark and Germany. Relatively high shares and rates for thinly populated areas were particularly common in Poland and Slovakia where these rural areas had the highest values for six of the seven income and living conditions indicators. By contrast, thinly populated areas had the lowest values for all seven indicators in the Netherlands and the lowest values for six of the seven indicators in the United Kingdom as well as Iceland.

The Czech Republic was the only EU Member State where none of the three types of area (according to the degree of urbanisation) recorded the highest or lowest rates for a majority of the seven income and living conditions indicators. Rather, poverty and social exclusion (and its sub-dimensions) was concentrated in thinly populated areas (other than the incidence of very low work intensity), while housing issues were more prevalent in densely populated, urban areas.

The risk of income related poverty was most prevalent among thinly populated areas in the majority of the EU Member States. By contrast, densely populated areas had the highest severe material deprivation rates and the highest prevalence of housing issues in a majority of the Member States, despite the fact that the EU-27 average was highest in thinly populated areas for three of these four indicators. As such, the share of people living in households with very low work intensity was the only indicator for which there was no clear pattern by type of area, as in 12 Member States the highest (or joint highest) values for this indicator were recorded in densely populated areas, for 11 Member States in thinly populated areas, and for the remainder in intermediate density areas.

Data sources and availability

There are a range of different territorial typologies that may be used to analyse the spatial distribution of socio-economic indicators. Traditionally, these were determined by population size and population density based on local administrative units at level 2 (LAU2) — in other words, communes, municipalities or local authorities. More recently, territorial typologies have used a population grid made up of 1 km² grid cells in order to define clusters or groups, which can then be aggregated to areas (LAU2) or regions (NUTS level 3).

Degree of urbanisation

The degree of urbanisation defines three types of area, using a criterion of geographical contiguity in combination with a minimum population threshold. In order to group the cells, three different rules for contiguity (contiguous cells are those which are neighbouring or adjoining cells) are applied to create clusters. The European Commission currently defines the degree of urbanisation, using population grid cells, as follows.

- Densely populated areas (alternatively referred to as cities, urban centres or urban areas): at least 50 % of the population lives in high-density clusters (in addition, each high-density cluster should have at least 75 % of its population in densely-populated LAU2s). High-density clusters are contiguous grid cells of 1 km² with a population density of at least 1 500 inhabitants per km² and a minimum population of 50 000 persons.

- Intermediate density area (alternatively referred to as towns and suburbs or small urban areas): less than 50 % of the population lives in rural grid cells (where rural grid cells are those outside of urban clusters) and less than 50 % live in high-density clusters;

- Thinly populated areas (alternatively referred to as rural areas): more than 50 % of the population lives in rural grid cells.

Analysing data by different territorial levels — such as a classification by degree of urbanisation — provides a unique insight into developments at local levels, and highlights differences between different types of area.

Statistics on income and living conditions

EU statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC) is the main European data source containing information relating to income, living conditions and social inclusion. The reference population for EU-SILC includes all private households and their current members residing in the territory (of the surveying country) at the time of data collection. Persons living in collective households and in institutions are generally excluded from the target population. All household members are surveyed, but only those aged 16 and above are interviewed. The survey was conducted on a total sample of 217 720 households across the EU in 2011.

As multi-dimensional concepts, poverty and social exclusion cannot easily be measured through statistics: as such, EU-SILC includes objective and subjective aspects in both monetary and non-monetary terms for households and individuals. These indicators may be analysed in conjunction with data from other domains (for example, demography, education and training, health, labour market or housing statistics) to study social inclusion in a more comprehensive way.

Indicator definitions

The at-risk-of-poverty or social exclusion rate is a composite indicator which combines information for the at-risk-of-poverty rate, severe material deprivation rate and the share of people living in households with very low work intensity. A person is considered to be at risk of poverty or social exclusion if he/she belongs to at least one of these categories.

The at-risk-of-poverty rate is the share of people with an equivalised disposable income (after social transfers) below the at-risk-of-poverty threshold, which is set at 60 % of the national median equivalised disposable income.

Material deprivation refers to a state of economic strain, defined as the enforced inability (due to a lack of resources and not because of choice) to pay for a range of goods and services; these items are considered by most people to be desirable or even necessary in order to have an adequate quality of life (in the European context). The severe material deprivation rate is defined as the enforced inability of households to pay for at least four of the following list of items: rent, mortgage or utility bills; keeping the home adequately warm; facing unexpected expenses; eating meat or other sources of protein every second day; going on a one week holiday away from home per year; ownership of a colour television set; ownership of a washing machine; ownership of a car; ownership of a telephone.

The share of people living in households with very low work intensity is defined as the proportion of the population aged 0–59 living in a household having a work intensity below the threshold of 0.20. The work intensity of a household is the ratio of the total number of months that all working-age household members have worked during the income reference year in relation to the total number of months the same household members could theoretically have worked in the same period. A working-age person is a person aged 18–59, with the exclusion of students aged 18–24; households composed only of children, of students aged less than 25, and/or people aged 60 or over are excluded. All persons aged 60 or over are excluded from the computation of this indicator regardless of their household type.

The overcrowding rate is defined as the percentage of the population living in an overcrowded household. A person is considered to be living in an overcrowded household if the household does not have at its disposal a minimum number of rooms equal to: one room for the household; one room per couple in the household; one room for each single person aged 18 or above; one room per pair of single people of the same gender aged 12–17; one room for each single person aged 12–17 and not included in the previous category; one room per pair of children aged less than 12.

The housing cost overburden rate is the percentage of the population living in households where total housing costs ('net' of housing allowances) represent more than 40 % of household disposable income ('net' of housing allowances).

The severe housing deprivation rate is defined as the percentage of population living in a dwelling which is considered as overcrowded (see above), while also exhibiting at least one out of three housing deprivation items. The housing deprivation items are: a leaking roof, damp walls, floors, foundation, or rot in window frames or floor; no bath or shower in the dwelling and no indoor flushing toilet for the sole use of the household; and a dwelling that is too dark.

Context

The EU seeks to promote territorial cohesion alongside economic and social cohesion, as detailed in the seventh progress report on economic, social and territorial cohesion (COM(2011) 776 final). ‘The European platform against poverty and social exclusion: a European framework for social and territorial cohesion’ (COM(2010) 758 final) is one of the seven flagship initiatives of the Europe 2020 strategy. Its goals are to: ensure economic, social and territorial cohesion; guarantee respect for the fundamental rights of people experiencing poverty and social exclusion, and enable them to live in dignity and take an active part in society; mobilise support to help people integrate in the communities where they live, get training and help them to find a job and have access to social benefits.

In order to monitor progress towards these aims, at the Laeken European Council in December 2001, European heads of state and government endorsed a first set of common statistical indicators relating to social exclusion and poverty that were subject to a continuing process of refinement by an indicators sub-group that is part of the social protection committee. These indicators are an essential element in the open method of coordination to monitor the progress of EU Member States in the fight against poverty and social exclusion; some of them are included in this article.

In the context of the Europe 2020 strategy, the European Council adopted in June 2010 a headline target on social inclusion, namely, for the EU-27 as a whole to have at least 20 million fewer people at risk of poverty or social exclusion by 2020.

The main EU instrument for supporting employability, fighting poverty and promoting social inclusion is the European Social Fund (ESF). This structural instrument invests directly in people and their skills and aims at improving their labour market opportunities. Yet some of the most vulnerable citizens who suffer from extreme forms of poverty are too far removed from the labour market to benefit from these social inclusion measures.

See also

Further Eurostat information

Publications

- Eurostat regional yearbook 2013 - Chapter 14

- Eurostat regional yearbook 2011 - chapter 16

Main tables

- Regional poverty and social exclusion statistics (t_reg_ilc)

Database

- Regional poverty and social exclusion statistics (reg_ilc)

Dedicated section

Methodology / Metadata

- Income and living conditions (ESMS metadata file — ilc_esms)

- Standard error estimation for the EU-SILC indicators of poverty and social exclusion - 2013 edition