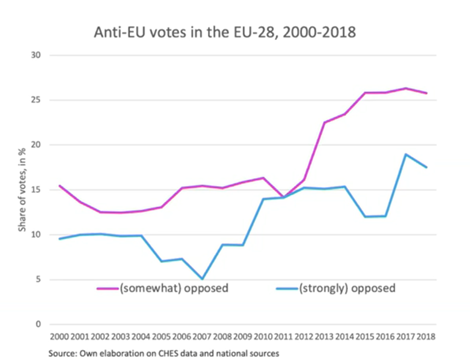

The research conducted by Lewis Dijkstra and Rodríguez-Pose suggests that Euroscepticism is fuelled by hubris and that a well-managed cohesion policy can keep the rise of this phenomenon in Europe at bay Defined as the opposition to the EU integration, Euroscepticism represents one of the major challenges facing Europe. According to the Chapel Hill Expert Survey, while in 2005 anti-European parties received just 25% of the votes of the Eurozone, in 2018 the figure rose to 45%. Low g

Guest post: Money cannot buy love, but it can persuade Eurosceptics

- 10 November 2020

The research conducted by Lewis Dijkstra and Rodríguez-Pose suggests that Euroscepticism is fuelled by hubris and that a well-managed cohesion policy can keep the rise of this phenomenon in Europe at bay

Defined as the opposition to the EU integration, Euroscepticism represents one of the major challenges facing Europe. According to the Chapel Hill Expert Survey, while in 2005 anti-European parties received just 25% of the votes of the Eurozone, in 2018 the figure rose to 45%. Low growth, youth unemployment, poor quality education, inequality… It is well known that the economic situation has been used by populist parties for questioning the EU’s promise, that is, to create greater prosperity across the continent through a single market. However, although the consequences of the recession have marked a turning point in the way citizens think of European institutions, poverty seems not to be the main cause of this phenomenon. Recent studies, submitted at the European Week of Regions and Cities (EWRC), show that rich regions also vote for anti-EU parties and that Cohesion Policy, if well managed, may play a positive role.

According to an empirical analysis led by Lewis Dijkstra, Head of the Economic Analysis Sector of the Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy, and Andrés Rodríguez-Pose, professor at the London School of Economics, Euroscepticism, unlike other issues, is a problem that covers a wide ideological spectrum, affecting all member states, particularly elderly population. In 2018 most Eurosceptic areas were located in UK, Germany, Austria, France, Italy, Hungary and Czech Republic. Moreover, most right-wing anti-EU ballots came from voters aged 40-64 living in rural areas with many migrants from non-EU countries; and most left-wing anti-EU ballots came from voters aged 65 and over living in cities with high-quality tertiary education.

Frustration and economic uncertainty

As regards economy, research on EU discontent was divided about whether poverty is a deciding factor. At first, Dijkstra and Rodríguez-Pose found that regions affected by Euroscepticism had in common a low economic growth and a progressive reduction in industrial jobs. However, in a second research, they discovered that those areas also registered a higher GDP per head and a better road network, and that they were also close to the national capital. Furthermore, some of the areas that voted heavily in favour of Brexit, such as Sheffield, had much profited from EU funds.

In this sense, Dijkstra and Rodríguez-Pose came to the conclusion that anti-EU voters are motivated not just by discontent about economic uncertainty, but also by discontent fuelled by hubris. “These regions, that used to be more affluent, but have relatively declined, may feel a lot of frustration and feel less likely to vote pro EU”, said Dijkstra during his intervention at the EU Regions Week 2020. According to him, people from those places are more susceptible to stereotypes such as public waste, maladministration, and vagrancy, and, consequently, they vote against EU integration.

Concerning the solution, Prof. Rodríguez-Pose argues that although putting more money is not a recipe, if well managed, it could play a key role in this combat. “Euroscepticism is a territorial issue, and, for this reason, a territorial solution is needed”, he stated. Based on the election results of France and Italy in 2017 and in 2018, he noticed a link between less Cohesion Policy spending and Euroscepticism: “We found that in those places where there had been more investment in EU cohesion, Eurosceptic parties experienced a lower share of votes. On the contrary, areas that had had less investments, accounted more Eurosceptic and populist votes. We end up always with the same situation: more investment seems to be connected to a lower vote in favour of Eurosceptic parties”.

However, the key to overcoming Euroscepticism may not to be funding, but funding intensity and the kind of investment. Rodriguez Pose and Dijkstra’s report shows that there are areas that are never relevant for this issue like transport, infrastructure, tourism, culture, urban and rural regeneration; and areas that seem less likely to quell rise of Euroscepticism such as business support, energy, environment, natural resources, and IT. By contrast, human resources, RTD and social infrastructure have a lot of influence on the reduction of Eurosceptic voting.

Social infrastructure: the main drive of pro-Europe voting

In this sense, it is evident that the European Union should invest in areas with a great impact. However, when we get down to details, things look less simple and easy. Euroscepticism depends not just on the area of investment, but also on a complex set of variables. For instance, increasing funds in human resources translates in the long term into a decrease of human resources productivity and thus, into a drop of pro-Europe voting. And, paradoxically, a soar in funds in environment and natural resources leads to a higher impact in terms of reducing pollution and Euroscepticism.

Nonetheless, experts agree that boosting investment in social infrastructure will always be beneficial. In fact, the highest returns in combatting Euroscepticism across the EU with cohesion policy funding (2000-2013) have been achieved with this kind of investment, as it is connected with a lower overall share of Eurosceptic vote and this effect increases as the investment in social infrastructure rises. In this sense, if the EU is to keep the rise of discontent in Europe at bay, it should start by focusing on more popular initiatives such as e-learning and infrastructures for health and long-term-care.

Moreover, in a context where most programmes designed to boost the sense of belonging to the EU have been seriously affected by the coronavirus, like the Erasmus programme, social infrastructure becomes not just the main tool in the struggle against the pandemic, but the only tool available against this crisis of identity.

Miguel Durán Díaz-Tejeiro, alumnus of the Youth4Regions programme for aspiring journalists

More information

Working paper: Does cohesion policy reduce EU discontent and Euroscepticism?