Archive:Key figures on the changes in the labour market

Data extracted in April 2021

Planned article update: October 2021

Highlights

The COVID-19 pandemic has slowed economic activity and, as a result, the labour market. It clearly had a negative impact on employment but also pushed out people of unemployment by affecting their availability or their job search.

This article aims to present the key consequences of the COVID-19 crisis on the labour market, focusing on employment, the total unmet demand for employment (also known as the labour market slack, further explained below under “Main facts”) and the share of people who are neither employed, available to work, nor looking. All three categories together refer to the entire population as a whole. This article provides an overview of the quarterly changes in the labour market in 2020 for the overall population, investigating the effects of the crisis at EU level and in the respective Member States, as well as in the EFTA countries and candidate countries. It makes use of quarterly and seasonally adjusted data from the European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS).

This article, along with the articles Labour market slack - the unmet need for employment and Employment, is part of the online publication Labour market in the light of the COVID 19 pandemic - quarterly statistics.

Full article

Main facts

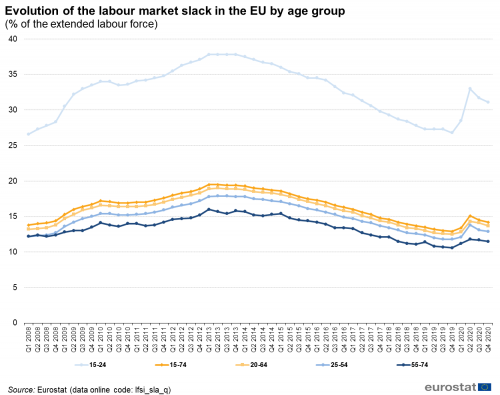

The most recent quarterly European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS) data provides an overview on the labour market in the four quarters of 2020, which can be compared with previous years. As shown in Figure 1, the labour market slack (meaning the unmet demand for employment) of people aged 20-64 reached 13.7 % of the extended labour force (which includes both those in employment and those in the labour market slack) in the fourth quarter of 2020 (29.1 million people). One year ago, in the fourth quarter of 2019, labour market slack accounted for 12.5 % of the total extended labour force. However, it rose to 14.3 % in the second quarter of 2020, when overall economic activity slowed dramatically.

It is worth noting that in addition to unemployed people the labour market slack includes the underemployed part-time workers and the potential additional labour force. The latter includes: (1) people who are available to work but are not looking for work and (2) people who are looking but are not immediately available. While the labour force only covers employed and unemployed individuals, the extended labour force also encompasses the previously mentioned potential additional labour force.

(% of the extended labour force)

Source: Eurostat (lfsi_sla_q)

Figure 2 presents the evolution of the employment rate by age group. In the fourth quarter of 2020, the employment rate of people aged 20 to 64 was 72.6 % (188.7 million people). It is 0.6 percentage points (p.p.) lower than the 73.2 % recorded in the fourth quarter of 2019. However, employment increased between Q2 2020 and Q4 2020 by 0.9 p.p, as it fell to 71.7 % in Q2 2020.

(in % of the total population)

Source: Eurostat (lfsi_emp_q)

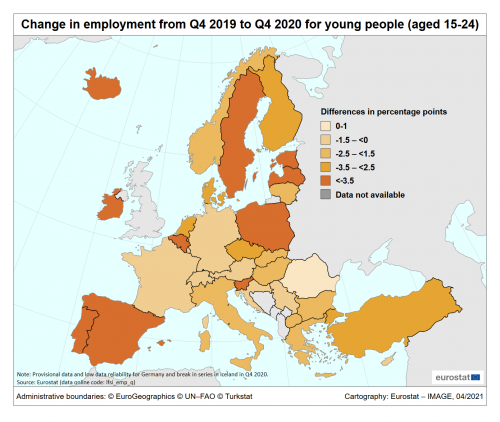

Based on Figures 1 and 2, it is clear that not all age groups were affected equally by the COVID-19 crisis. Young people aged 15-24 experienced the largest drop in employment and the greatest increase in labour market slack during the health crisis when compared to other age groups. Map 1 depicts changes in the employment rate of young people (aged 15 to 24) by country from Q4 2019 to Q4 2020.

(in percentage points (p.p.), Q4 2020 compared to Q4 2019)

Source: Eurostat (lfsi_emp_q)

Given that people aged 15-24 were the most affected by the health crisis as regards their participation in the labour force, and as the labour market slack mainly includes the unemployment and the potential additional labour force with people aged 15 to 74 serving as the reference population, the following sections will focus on people aged 15-74 (instead of people aged 20-64 as before in this article).

On the other hand, as both the labour market slack and employment include the underemployed part-time workers in their usual definition, the next sections will consider the group of employed people excluding the underemployed part-time workers, i.e. the group of full-time workers and part-time workers not wishing to work more. This will avoid a double-counting of the underemployed part-time workers.

Why is focusing solely on unemployment insufficient?

Together with employment, labour market slack better reflects the effects of the economic crisis than unemployment

The economic downturn has had an impact on employment in recent quarters. At EU level, the share of employed people in the total population aged 15-74 fell by 1.8 p.p. in just six 6 months, from Q4 2019 to Q2 2020. Similarly to what happened at EU level, the proportion of employed people decreased in all EU Member States, albeit to varying degrees, as further explained.

Typically, in times of economic crisis, unemployment (which includes people who are not employed, available and looking for a job) is the primary indicator to report on the deterioration on the labour market. Nonetheless, the nature of the COVID-19 crisis, which began as a health crisis before progressing to an economic crisis, altered the reference frame. Measures taken by European governments to contain the spread of the virus, disrupted business and public entities such as schools. As a result, jobless people who would have been available to work and would have sought employment, may have given up their search due to low return expectations, or may no longer be available due to childcare. These people, who are still connected to the labour market but are experiencing exceptional circumstances, are not considered "unemployed" under the International Labour Organisation (ILO) criteria, but are included in the labour market slack, revealing the unmet demand for employment more clearly. For further explanations on the concept of the labour market slack and a detailed analysis by gender, see the Labour market slack in detail article.

In Q4 2020, 57.5 % of the total population aged 15 to 74 in the EU was working full-time or working part-time but not wishing to work more, while 9.5 % faced an unmet demand for employment. This portion is divided as follows: 1.9 % were underemployed part-time workers, 4.6 % were unemployed according to the ILO criteria, 0.5 % were seeking work but were not immediately available, and 2.5 % were available to work but did not seek. The remaining population which accounted for 33.0 % of the total population is considered outside the extended labour force which means that they are jobless persons neither available to work nor seeking. All these shares are displayed in Figure 3 and in the visual at the top of this article for a better understanding. In order to reflect the changes in the whole population without overlapping, the group made of full-timers and part-timers not wishing to work more is considered instead of the group of employed people (as underemployed part-time workers are included in the labour market slack).

(in % total population aged 15-74, Q4 2020)

Source: Eurostat (lfsi_sup_q) and (une_rt_q)

Specific developments quarter by quarter in the EU

Over the last quarters, visible changes occurred in the labour market as shown in Figure 4. From Q4 2019 to Q1 2020, at the very beginning of the health crisis, the slight decrease in the group of part-timers not wishing to work more and full-timers (-0.4 p.p.) at EU level was mainly offset by an increase in the share of people available to work but not seeking (+0.3 p.p.). In the following quarter, Q2 2020, characterised by the first lockdowns, the share of part-timers not wishing to work more and full-timers dropped by 1.4 p.p. Even though most countries have taken measures to reduce job losses, it is widely assumed that businesses froze or reduced hiring or did not renew a portion of temporary contracts, as shown in this employment article. This fall in the group of part-timers not wishing to work more and full-timers produced an increase in the labour market slack (+1.0 p.p.) and in the share of people outside the extended labour force, those neither seeking nor available (+0.4 p.p.). The rise in the labour market slack was mainly due to an increase in the share of people available but not seeking (+1.0 p.p.) while the share of unemployed people remained almost stable (+0.1 p.p.).

From Q2 2020 to Q3 2020, corresponding to the summer season and the partial restart of many businesses, the share of part-timers not wishing to work more and full-timers aged 15-74 increased by 0.5 p.p. to 57.1 %. This upturn was accompanied by a slight decline in the slack, the unmet demand for employment (-0.2 p.p.). Speaking of this period, it appears that people began looking for work again, as the near-stable slack conceals a noticeable increase in the share of unemployed people meeting the ILO criteria (+0.5 %), offset by a decrease in people available to work but not seeking work (-0.8 %). In addition, the share of people outside the extended labour force neither available nor seeking also recorded a drop of 0.3 p.p.

Compared to Q3 2020, the share of part-timers not wishing to work more and full-timers kept on increasing in Q4 2020 (+0.4 p.p.), accounting for 57.5 % of the total population. In parallel, the labour market slack turned back for the second consecutive quarter, decreasing by 0.3 p.p. This decrease is due to two factors: a decrease in unemployment (-0.2 p.p.) and in the share of underemployed part-time workers (-0.1 p.p.).

(in percentage points, 15-74)

Source: Eurostat (lfsi_sup_q) and (une_rt_q)

Sharpest declines in part-timers not wishing to work more and full-timers in Ireland and Spain

Looking at the quarterly developments among the EU Member States, not all countries went the same way as regards the group of part-timers not wishing to work more and full-timers. The vast majority of countries were impacted the most in Q2 2020, when the share of group of part-timers not wishing to work more and full-timers aged 15-74 declined in 16 out of 27 Member States by 1 p.p. or more. All changes are reported by category and by country in Figure 5. Ireland and Spain reported the most substantial decreases from quarter to quarter among the Member States over the past year. The share of part-timers not wishing to work more and full-timers dropped by 3.2 p.p. both in Ireland and in Spain in the second quarter of 2020. Estonia and Italy reported the third and the fourth biggest falls in the share of part-timers not wishing to work more and full-timers, as it went down by 2.7 p.p. in Estonia and by 2.3 p.p. in Italy in the second quarter.

Between Q3 2020 and Q4 2020, the share of part-timers not wishing to work more and full-timers aged 15-74 increased at EU level (+0.4 p.p.) but to a lesser extent than the growth reported between the two previous quarters, namely Q2 and Q3 2020 (+0.5 p.p.). Nonetheless, this development at EU level has not had the same impact across all EU Member States. Between the second and third quarters of 2020, the share of part-timers not wishing to work more and full-timers increased in 16 countries, decreased in 6, and remained stable in 5. In Italy, Spain, Bulgaria, Ireland and Austria, the share of part-timers not wishing to work more and full-timers increased by even more than 1 p.p. For comparison, the share of part-timers not wishing to work more and full-timers increased in 20 countries between Q3 and Q4 2020, with only two countries, namely Luxembourg and Portugal, experiencing growth rates greater than 1 p.p.. It also decreased in seven countries. So, fewer countries reported increases in their group of part-timers not wishing to work more and full-timers between Q2 and Q3 2020, but those increases were sharper than those reported between Q3 and Q4 2020, when more countries reported increases but they were weaker than those observed between Q2 and Q3 2020.

(People aged 15-74,quarter-on-quarter comparison, in p.p., protocol order 1st set)

Source: Eurostat (lfsi_sup_q) and (une_rt_q)

(People aged 15-74,quarter-on-quarter comparison, in p.p., protocol order 2d set)

Source: Eurostat (lfsi_sup_q) and (une_rt_q)

By contrast, the labour market slack rose the most in Ireland, Spain and Austria in the second quarter of 2020, all three recording an increase exceeding 2 p.p. in the unmet demand for employment. Afterwards, the slack recorded a higher decline than in other countries in Q3 2020 in Italy (-1.4 p.p.) and in Q4 2020 in Luxembourg (-1.5 p.p.).

The share of people outside the extended labour force went up sizably in Q2 2020 in Estonia (+1.7 p.p.) where it went down also the most in Q3 2020 (-1.3 p.p).

Where were we before 2020 and at the end of 2020?

The comparison of Q4 2020 to Q4 2019 (the quarter just before the start of the health crisis) provides some indication of the potential labour market recovery, as shown in Figure 6. Only a few countries returned to pre-crisis levels for the group of part-timers not wishing to work more and full-timers in Q4 2020. These countries are Luxembourg, Greece and Malta, where the share of part-timers not wishing to work more and full-timers in Q4 2020 exceeded the share recorded in Q4 2019 (+0.6 p.p., +0.5 p.p. and +0.3 p.p. respectively) and Poland where it remained stable. In contrast, the most affected countries, where the share of part-timers not wishing to work more and full-timers fell by 2 p.p. or more between Q4 2019 and Q4 2020, are Estonia (from 68.7 % in Q4 2019 to 66.0 % in Q4 2020, a 2.7 p.p. drop), Spain (from 52.6 % to 50.5 %, -2.1 p.p.), and Ireland (from 61.2 % to 59.2 %, -2.0 p.p.). Over the same period, the cut in the share of part-timers not wishing to work more and full-timers was between -1.9 p.p. and -1.0 p.p. in Austria, Latvia, Sweden, Lithuania, Finland, Bulgaria, Italy, Germany, Slovakia, Cyprus, Croatia, Portugal and the Netherlands, and between -0.9 p.p. and -0.1 p.p. in Belgium, Czechia, Slovenia, Romania, Hungary, France and Denmark.

In Q4 2020, the unmet demand for employment (i.e. the labour market slack) exceeded by 2 p.p. or more the level of Q4 2019 in Estonia (+3.3 p.p.), Spain (+2.5 p.p.), Austria (+2.3 p.p.), Lithuania and Ireland (both +2.2 p.p.) and Cyprus (+2.0 p.p.). Greece and France were the only EU countries where the unmet demand for employment was smaller in Q4 2020 than in Q4 2019 (-0.3 p.p. and -0.1 p.p. respectively).

(in % of total population aged 15-74)

Source: Eurostat (lfsi_sup_q) and (une_rt_q)

<sesection>

Who were the most affected by the crisis?

COVID-19 crisis hit young people more than people aged 25 years or more

Between Q4 2019 and Q2 2020, the increase of the unmet demand for employment expressed as a percentage of the extended labour force was much sharper among young people aged 15-24 (+6.2 p.p. between both quarters), far from the increases observed for people aged 25-54 (+2.0 p.p.) and for people aged 55-74 (+1.2 p.p.) as shown in Figure 1. Nonetheless, between Q2 2020 and Q4 2020, the unmet demand for employment among young people decreased more (-1.9 p.p.) than for the other age groups, namely people aged 25-54 (-0.9 p.p.) and people aged 55-74 (-0.3 p.p.). However, the decrease in the labour market slack of young people in the third and fourth quarters was far from balancing out the sharp rise recorded at the beginning of the health crisis as also shown in Figure 1.

Looking at Figure 7 that reports on the quarterly development of the population aged 15-24 by country, it is clear that a country showing a low share of the unmet demand for employment does not automatically show a high share of part-timers not wishing to work more and full-timers. Beyond the picture reflecting more structural features of the labour market, fluctuations often respond to the following pattern: a decrease in the unmet demand for employment accompanies an increase in the share of part-timers not wishing to work more and full-timers, and reciprocally like in the Netherlands or Hungary in Q3 2020. Nevertheless, in some cases, the labour market slack did not offset at all a decrease in the share of part-timers not wishing to work more and full-timers, making the category outside the extended labour force bigger as it occurred in Malta and Bulgaria in Q1 2020 or Portugal in Q2 2020.

Between the first and second quarters of 2020, young people were the most affected in Ireland, the Netherlands, Estonia, Slovenia and Spain, where the share of young people working part-time and not wishing to work more or working full-time fell by more than 4 p.p.. From the second to the third quarter of 2020, a rebound higher than 2 p.p. was recorded in the Netherlands, Ireland and France (metropolitan). As regards the latest development, from Q3 2020 to Q4 2020, the share of young people working part-time and not wishing to work more or working full-time decreased by 1 p.p. or more in Malta and Ireland (both -1.7 p.p.), Hungary and Belgium (both -1.1 p.p.), and increased by more than 2 p.p. in Cyprus, Lithuania and Romania.

As regards the slack, from Q1 to Q2 2020, the highest increases in the share of people facing an unmet demand for employment aged 15-24 were found in the Netherlands (+5.7 p.p.), Ireland (5.3 p.p.) and Croatia (+4 p.p.). From Q2 to Q3 2020, the slack of young people decreased the most in Latvia (-4.7 p.p.), Croatia (-3.5 p.p.), the Netherlands (-2.6 p.p.) and Austria (-2.2 p.p.) but still increased by more than 2 p.p. in Estonia (+2.8 p.p.) and Cyprus (+2.7 p.p.). The fourth quarter of 2020 compared to the third quarter of 2020 showed lower variations: largest increases in Croatia (+1.6 p.p.) and Latvia (+1.4 p.p.), and largest decreases in Spain (-1.3 p.p.), Lithuania (-1.2 p.p.) and Ireland (-1.1 p.p.).

People aged 55 to 64 were maintained in employment

With respect to the population aged 25-54 (see Figure 8), the share of part-timers not wishing to work more and full-timers was higher than 75% in all countries in Q4 2020, except in Spain, Italy and Greece with 69.2 %, 67.6 % and 67.5 % respectively. The percentages for people aged 25-54 fluctuated much less over the quarters of 2020 than for young people. However, drops equal to or exceeding 2 p.p. have been reported in Spain (-4.0 p.p.), Bulgaria (-3.5 p.p.), Italy (-3.1 p.p.), Ireland (-3.0 p.p.) and Austria (-2.7 p.p.) in Q2 2020. Consecutively, in Q3 2020, the share of part-timers not wishing to work more and full-timers sharply increased in Italy (+2.6 p.p.) and in Spain (+2.3 p.p.). At the end of 2020, from Q3 to Q4 2020, the share of part-timers not wishing to work more and full-timers went up by more than 2 p.p. in Luxembourg (+2.7 p.p.) and Malta (+2.3 p.p.).

In the second quarter of 2020, the share of people aged 55-74 who were part-timers not wishing to work more or full-timers amounted to 36.2 % of the total EU population against 36.8 % two quarters earlier (-0.6 p.p.) (see Figure 9). However, from the second quarter to the fourth quarter of 2020, this share increased by 0.4 p.p. to reach 36.6 %, almost its level of the fourth quarter of 2019. Focusing on national level, Lithuania, Estonia and Romania registered the biggest decreases in the share of part-timers not wishing to work more and full-timers in Q2 2020 compared to Q1 2020 for this age group (between -2. p.p. and -1 p.p.). By contrast, in Slovenia, the share of part-timers not wishing to work more and full-timers aged 55-74 increased by 1.5 p.p. during the same period. In the third quarter of 2020, increases higher than 1 p.p. were recorded in Portugal (+1.3 p.p.), Lithuania (+1.2 p.p.) and Greece (+1.1 p.p.). No EU Member States registered decreases greater than 1 p.p. during this period. Finally, in the fourth quarter of 2020, Slovenia and Portugal showed the biggest variations compared to the third quarter of 2020, respectively +1.2 p.p. and +1.1 p.p.

Regarding people aged 55 to 64, approximately six out of 10 persons in the EU were employed in Q4 2019, 59.7 % exactly (see Figure 2 at the top of the article). Within the two first quarters of 2020, the share slightly decreased (-0.5 p.p.) to reach 59.2 %. However, the last two quarterly variations amounted each to +0.5 p.p., and the share of employed people aged 55-64 was consequently higher in Q4 2020 than in Q4 2019, accounting for 60.2 % of the total population. It is worth noting that increases in employment for people aged 55 to 64 are likely due to job retention instead of recent job starters.

(in % of the total population)

Source: Eurostat (lfsi_sup_q) and (une_rt_q)

(in % of the total population)

Source: Eurostat (lfsi_sup_q) and (une_rt_q)

(in % of the total population)

Source: Eurostat (lfsi_sup_q) and (une_rt_q)

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

All figures in this article are based on seasonally adjusted quarterly results from the European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS).

Source: The European Union labour force survey (EU-LFS) is the largest European household sample survey providing quarterly and annual results on labour participation of people aged 15 and over as well as on persons outside the labour force. It covers residents in private households. Conscripts in military or community service are not included in the results. The EU-LFS is based on the same target populations and uses the same definitions in all countries, which means that the results are comparable between countries.

European aggregates: EU refers to the sum of EU-27 Member States.

Country note: In Germany, from the first quarter of 2020 onwards, the Labour Force Survey (LFS) has been integrated into the newly designed German microcensus as a subsample. Unfortunately, for the LFS, technical issues and the COVID-19 crisis have had a large impact on the data collection processes, resulting in low response rates and a biased sample. For this reason, the full sample of the whole microcensus has been used to estimate a restricted set of indicators for the four quarters of 2020 for the production of LFS Main Indicators. These estimates have been used for the publication of German results, but also for the calculation of EU and EA aggregates. By contrast, EU and EA aggregates published in the Detailed quarterly results (showing more and different breakdowns than the LFS Main Indicators) have been computed using only available data from the LFS subsample. As a consequence, small differences in the EU and EA aggregates in tables from both collections may be observed. For more information, see here.

Definitions: The concepts and definitions used in the Labour Force Survey follow the guidelines of the International Labour Organisation.

Five different articles on detailed technical and methodological information are linked from the overview page of the online publication EU Labour Force Survey.

Seasonally adjustment models: Some of the EU-LFS based seasonally adjusted data published this quarter has been revised substantially. Indeed, the outbreak of the COVID-19 crisis actually lead to a major shock into the series. The impact of COVID-19 on a number of indicators have been explicitly modelled as outliers, and the combined effect of this shock and the new identification of the models explains the observed revisions. The methodological choices of Eurostat in terms of seasonal adjustment in the COVID period are summarised in the methodological paper: "Guidance on time series treatment in the context of the COVID-19 crisis". These choices assure the quality of the results and the optimal equilibrium between the risk of high revisions and the need for meaningful figures, as less as possible affected by random variability due to the COVID shock.

Context

The COVID-19 pandemic hit Europe in January and February 2020, with the first cases confirmed in Spain, France and Italy. COVID-19 infections have since been diagnosed in all European Union (EU) Member States. To fight the pandemic, EU Member States have taken a wide variety of measures. From the second week of March, most countries closed retail shops, with the exception of supermarkets, pharmacies and banks. Bars, restaurants and hotels were also closed. In Italy and Spain, non-essential production was stopped and several countries imposed regional or even national lock-down measures which further stifled economic activities in many areas. In addition, schools were closed, public events were cancelled and private gatherings (with numbers of persons varying from 2 to over 50) banned in most EU Member States.

The majority of the preventative measures were taken during mid-March 2020, and most of the measures and restrictions were in place for the whole of April and May 2020. The first quarter of 2020 was consequently the first quarter in which the labour market across the EU was affected by COVID-19 measures taken by Member States.

Employment and unemployment as defined by the ILO concept are, in this particular situation, not sufficient to describe the developments taking place in the labour market. In the first phase of the crisis, active measures to contain employment losses led to absences from work rather than dismissals, and individuals could not look for work or were not available due to the containment measures, thus not counting as unemployed.

The three indicators supplementing the unemployment rate presented in this article provide an enhanced and richer picture than the traditional labour status framework, which classifies people as employed, unemployed or outside the labour force, i.e. in only three categories. The indicators create ‘halos’ around unemployment. This concept is further analysed in a Statistics in Focus publication titled "New measures of labour market attachment", which also explains the rationale of the indicators and provides additional insight as to how they should be interpreted. The supplementary indicators neither alter nor put in question the unemployment statistics standards used by Eurostat. Eurostat publishes unemployment statistics according to the ILO definition, the same definition as used by statistical offices all around the world. Eurostat continues publishing unemployment statistics using the ILO definition and they remain the benchmark and headline indicators.

Direct access to

- New measures of labour market attachment - Statistics in focus 57/2011

- European Union Labour force survey - selection of articles (Statistics Explained)

- LFS main indicators (lfsi)

- Unemployment - LFS adjusted series (une)

- Supplementary indicators to unemployment - annual data (lfsi_sup_a)

- Supplementary indicators to unemployment - quarterly data (lfsi_sup_q)

- Unemployment - LFS adjusted series (une)

- LFS series - Detailed annual survey results (lfsa)

- Total unemployment - LFS series (lfsa_unemp)

- Supplementary indicators to unemployment by sex and age (lfsa_sup_age)

- Supplementary indicators to unemployment by sex and educational attainment level (lfsa_sup_edu)

- Supplementary indicators to unemployment by sex and citizenship (lfsa_sup_nat)

- Total unemployment - LFS series (lfsa_unemp)

- LFS series - Detailed quarterly survey results (lfsq)

- Total unemployment - LFS series (lfsq_unemp)

- Supplementary indicators to unemployment by sex and age (lfsq_sup_age)

- Supplementary indicators to unemployment by sex and educational attainment level (lfsq_sup_edu)

- Total unemployment - LFS series (lfsq_unemp)