SDG 1 - No poverty

End poverty in all its forms everywhere

Data extracted in April 2024.

Planned article update: June 2025.

Highlights

This article is a part of a set of statistical articles, which are based on the Eurostat publication ’Sustainable development in the European Union — Monitoring report on progress towards the SDGs in an EU context — 2024 edition’. This report is the eighth edition of Eurostat’s series of monitoring reports on sustainable development, which provide a quantitative assessment of progress of the EU towards the SDGs in an EU context.

SDG 1 calls for the eradication of poverty in all its manifestations. It envisions shared prosperity, a basic standard of living and social protection benefits for people everywhere, including the poorest and most vulnerable.

Full article

No poverty in the EU: overview and key trends

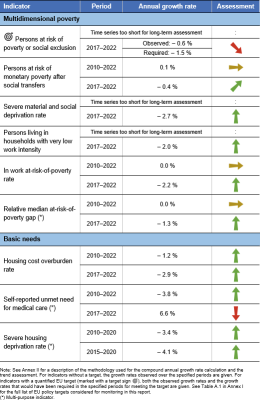

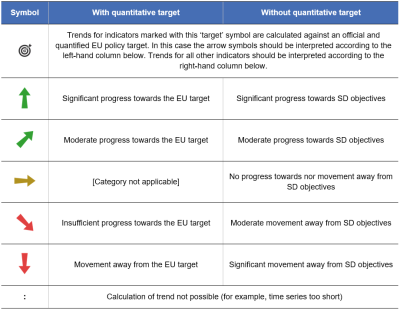

Poverty harms people’s lives and hampers social cohesion and economic growth. Monitoring SDG 1 in an EU context involves tracking aspects related to multidimensional poverty and basic needs. Over the assessed five-year period, the EU has made progress towards reducing the different aspects of poverty monitored here, but the overall pace has slowed compared with previous years. The composite indicator for multidimensional poverty shows that the number of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion has remained broadly stable since 2019. This is also due to the significant EU and national level measures to mitigate the negative social impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing cost of living crisis. The individual components of multidimensional poverty improved between 2017 and 2022, namely monetary poverty, social- and material deprivation, and low work intensity. However, significant further efforts will be required to meet the target set for multidimensional poverty to lift at least 15 million people out of poverty or social exclusion by 2030, compared with the 2019 level, along with the complementary ambition that at least 5 million of these should be children. Regarding basic needs, fewer people are now overburdened by housing costs or living in an overcrowded household. However, more people have been reporting an unmet need for medical care in 2022 than five years earlier.

Multidimensional poverty

SDG 1 does not only call for the eradication of extreme poverty but also for poverty in all its dimensions to be halved by 2030. This global goal has a universal approach to reducing poverty. The EU also employs a multidimensional measure of poverty and in its European Pillar of Social Rights Action Plan has set the target to reduce the number of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion by at least 15 million by 2030 compared with the situation in 2019. A complementary ambition states that of these 1 million people, at least 5 million should be children.

The EU’s at-risk-of-poverty-or-social-exclusion (AROPE) indicator is based on three components: monetary poverty (at-risk-of-poverty rate, AROP), severe material and social deprivation, and very low work intensity. Through this multidimensional approach, the indicator shows which share of the population is at risk of exclusion and marginalisation from economic and social activities [1].

Significant further efforts will be needed to meet the 2030 target to reduce the number of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion

In 2022, 95.3 million people, equalling 21.6 % of the EU population, were at risk of poverty or social exclusion. While this represents a 2.9 % decrease since 2017, when 98.1 million people (or 22.4 % of the population) had been at risk, the number has remained broadly stable since 2019. As a consequence, despite cushioning the negative social impacts of the COVID-19 and the inflation crises, significant further efforts will be needed to meet the EU target of lifting at least 15 million people out of poverty or social exclusion by 2030. It is worth noting that the trends related to monetary poverty — and thus in the overall risk of poverty or social exclusion indicator — might be affected by methodological changes in data collection from 2020 onwards in a few Member States [2].

The number of children (persons aged less than 18 years) who are at risk of poverty or social exclusion amounted to 20.0 million in 2022, corresponding to 24.7 % of the population of this age group. This is a 2.1 % decrease compared with five years earlier, when 20.4 million children (25.1 %) were at risk of poverty or social exclusion across the EU. Nevertheless, the EU is currently not on track to meet the complementary ambition of lifting at least 5 million children out of poverty or social exclusion by 2030.

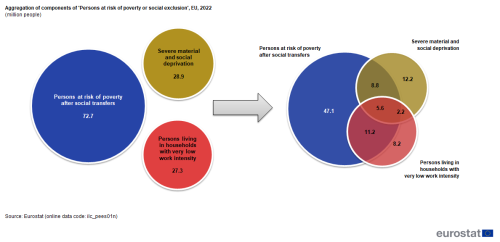

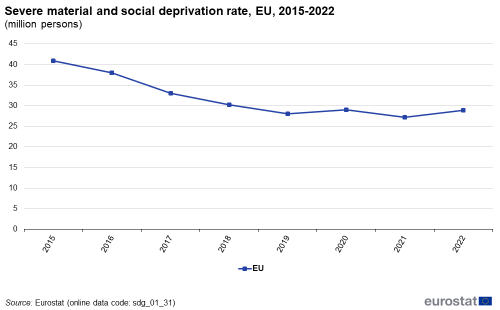

Monetary poverty is the main form of poverty or social exclusion in the EU

Monetary poverty was the most prevalent component of poverty or social exclusion in the EU in 2022, affecting 72.7 million people or 16.5 % of the population [3]. This means that after social transfers (other than pensions) these people had an equivalised disposable income of less than 60 % of the national median equivalised disposable income. The equivalised disposable income is a household’s total income — after tax and other deductions — that is available for spending or saving, divided by a specific scale which takes into account the household’s composition and size (all household members have the equivalised disposable income). 28.9 million people (6.7 % of the EU population) were affected by severe material and social deprivation in 2022, which meant they were unable to afford seven or more items out of a list of 13 elements of material goods, services or social activities considered by most people to be desirable or necessary for an adequate life. In the same year, very low work intensity, referring to people living in (quasi-)jobless households where the adults worked equal to or less than 20 % of their total work-time potential during the past year, affected 27.3 million people aged less than 65 years (equalling 8.3 % of the population from this age group).

The three components of the at-risk-of-poverty-or-social-exclusion indicator — monetary poverty, very low work intensity, and severe material and social deprivation — are related but distinct concepts that can overlap. This means that some people might be affected by two or even all three dimensions at the same time. According to its definition, monetary poverty is a relative measure and strongly depends on the median income level in a given country. This means that even during times of increasing median income, the relative poverty rate may remain stable or even increase, depending on changes in income distribution across the population. Rates of people living in households with very low work intensity (jobless or quasi-jobless households) and severe material and social deprivation (indicating a lack of resources to cover certain material and social needs) are likely to decrease during economic recoveries when people are generally better off financially and the labour market situation has improved. Of all the 95.3 million people at risk of poverty or social exclusion in the EU in 2022, 27.9 million were affected by more than one dimension of poverty, and 5.6 million were affected by all three forms.

To reduce poverty, governments provide a wide range of measures, such as income support though various benefits (for example, unemployment benefits, sickness and invalidity benefits, and minimum income benefits), tax policies and provision of enabling, social and employment services. The impact of the transfers on poverty reduction can be assessed by comparing the at-risk-of-poverty rate before and after social transfers, excluding pensions. In the EU, social transfers (other than pensions) reduced the share of people at risk of poverty in 2022 from 25.4 % [4] to 16.5 %, which corresponds to a reduction by 35.0 % [5].

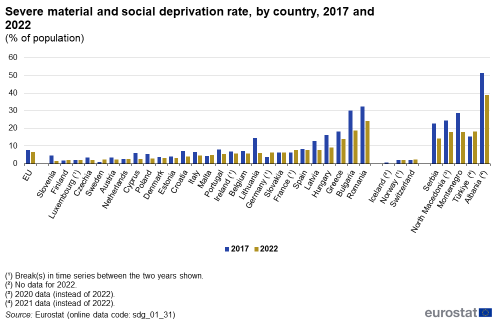

Considerable differences in poverty rates exist within the EU

The multidimensional risk-of-poverty-or-social-exclusion rate differs considerably between Member States. In 2022, national rates for this indicator ranged from 11.8 % in Czechia to 34.4 % in Romania. While Czechia ranked among the best performing countries for all three components, other countries show striking differences in their situation in terms of monetary poverty, severe material and social deprivation, and very low work intensity. This illustrates that good performance on one indicator does not necessarily go hand in hand with a similar performance on another one. Romania, for example, had one of the highest shares of monetary poverty after social transfers and the highest share of severely materially and socially deprived people in 2022, while at the same time its share of (quasi-)jobless households was one of the lowest across the EU. Finland is another example with striking differences between the three components. It had the second lowest rate of people affected by severe material and social deprivation and was among the countries with the lowest risk of monetary poverty after social transfers, but it had the third highest share of (quasi-)jobless households. These examples show that the drivers behind Member States’ at-risk-of-poverty-or-social-exclusion rates can vary, depending on the national context.

Children and young people are particularly affected by poverty and social exclusion

Children and young people are generally more affected by the risk of poverty or social exclusion than other age groups. People aged 15 to 24 were the most likely to be at risk in 2022, with 26.5 % of this age group living in households that were at risk of poverty or social exclusion [6]. This figure is 4.9 percentage points higher than the rate for the total EU population (21.6 %). Children aged less than 18 were also more affected than the overall EU population, with 24.7 % living in households at risk of poverty or social exclusion. The poverty or social exclusion levels for children fell between 2017 and 2022. However, and in line with the overall trend, significant further efforts will be required to meet the 2030 target of reducing the number of children at risk of poverty or social exclusion by at least 5 million compared to 2019.

Children aged less than 18 show a similar pattern for the three poverty dimensions as the total population, with monetary poverty being the most prevalent form, followed by material and social deprivation and quasi-joblessness. In 2022, 19.3 % of children aged less than 18 were living in households affected by monetary poverty after social transfers, 8.4 % were living in households affected by severe material and social deprivation, and 7.6 % were living in (quasi-)jobless households [7].

Children’s risk of poverty or social exclusion is largely determined by their parents’ situation. Two major factors are education and household composition: parents with a lower level of education usually earn less. In 2022, 61.9 % of children aged 0 to 17 whose parents had at most lower secondary education were at risk of poverty or social exclusion. Very young children aged 0 to 5 were the most affected, with a rate of 66.2 %. Children with more highly educated parents fared significantly better. 29.6 % of children aged 0 to 17 and 29.7 % of children aged 0 to 5 whose parents had a mid-level education were at risk of poverty or social exclusion. The rates were 10.2 % for children aged 0 to 17 and 10.7 % for children aged 0 to 5 with highly educated parents [8]. Similarly, households of (mostly female) single parents with one or more dependent children had a much higher at-risk rate (43.5 % in 2022) than any other household type [9].

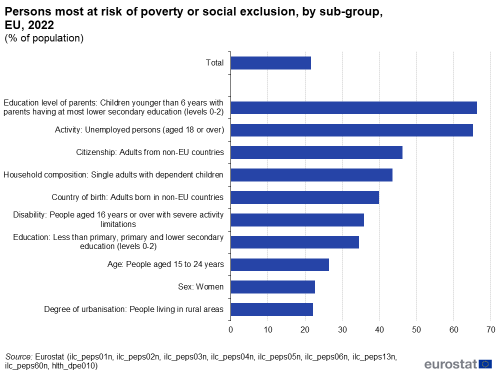

People who are unemployed, come from a migrant background, or have a low level of education or a disability are more prone to poverty

Identifying situations that can make people more vulnerable to being at risk of poverty and social exclusion is important for designing sound policies that prevent and fight poverty. Figure 4 shows which subgroups of people were most at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2022. In addition to the case of children and young people discussed previously, other characteristics — such as unemployment, a migrant background, low education levels or disabilities — were also key risk factors. Not surprisingly, the group with the highest at-risk-of-poverty-or-social-exclusion rate were unemployed people aged 18 years and over, of which two-thirds (65.2 %) were in this situation. Almost half (46.2 %) of non-EU citizens living in the EU were at risk of poverty and social exclusion, far more than EU home-country nationals (19.3 %). The situation was similar when looking at country of birth, with 39.9 % of adults born in non-EU countries being in that situation, compared with only 18.8 % of those born in the reporting EU countries. Moreover, more than one-third of people with severe disabilities (35.9 %) or low education levels (34.5 %) were at risk of poverty or social exclusion. People living in rural areas (22.1 %) were slightly more affected than those in urban areas (21.7 %). Women (22.7 %) were more affected than men (20.8 %) [10].

Due to recent improvements, the poverty gap has fallen back to the level reported in 2010

The poverty gap measures how far below the poverty line people’s incomes fall. It is calculated as the difference between the median income of those at risk of poverty and the poverty threshold , which is set at 60 % of the national median equivalised disposable income after accounting for social benefits. In 2022, the median income of those below the poverty threshold was 23.1 % lower than the threshold itself. This represents a 1.6 percentage point improvement compared with 2017. However, the long-term trend is characterised by stagnation, because the poverty gap in 2022 was the same as the 2010 level. Rates vary considerably across the EU in 2022. Finland had the lowest poverty gap with 14.8 % and Romania the highest with 32.0 %, followed by Spain with 27.8 %.

In-work poverty has fallen considerably during the past few years, reaching the same level as in 2010

Having a paid job does not necessarily prevent people from being at risk of poverty. In 2022, the share of people at risk of monetary poverty among the employed — the so-called working poor (in-work poverty) — stood at 8.5 %, which is the same as the 2010 level. Nevertheless, the 2022 figure represents a 1.0 percentage point improvement in the in-work poverty rate compared with 2017, when 9.5 % of employed people were affected. Rates varied considerably across the EU in 2022, with the lowest share of in-work-poverty recorded in Finland (2.5 %) and the highest in Romania (14.5 %) and Luxembourg (12.9 %). The likelihood of a person becoming ‘working poor’ varies according to their type of employment contract, education level and nationality. Low-skilled workers, people who work part-time or on temporary contracts, as well as people born outside the EU or who do not have EU citizenship are generally the most affected [11].

Basic needs

Being at risk of poverty can have a severe impact on a person’s ability to meet their basic needs such as being able to afford adequate housing or receive necessary medical treatment.

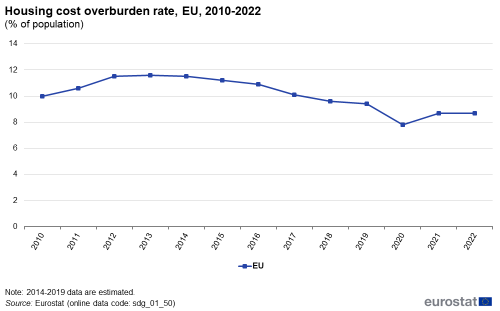

Fewer people are overburdened by their housing costs or face severe housing deprivation

The European Pillar of Social Rights, in principle 19, stipulates that access to social housing or housing assistance of good quality shall be provided for those in need. Meeting basic human needs is central to social sustainability and housing is a key dimension. The costs for housing often account for the largest component of many households’ expenditure and determine what is left of a household’s budget for satisfying other essential needs and expenses, such as food, energy, medical treatment or education. People suffering from poverty are far more often restricted to sub-optimal housing than the overall population.

Housing affordability can be analysed through the housing cost overburden rate, which is defined as the share of the population living in households where the total housing costs (net of housing allowances) represent more than 40 % of the total disposable household income. The EU’s housing cost overburden rate has been on a downward path since 2010, when 10.0 % of the population were affected, falling to 8.7 % in 2022. Low-income households are particularly prone to being overburdened by their housing costs. In 2022, 33.1 % of people with an income below the poverty threshold spent 40 % or more of their household disposable income on housing, compared with only 3.9 % of the not at-risk-of-poverty population (referring to people with an income above the poverty threshold).

The severe housing deprivation rate is an indicator of inadequate housing, referring to people living in an overcrowded household [12] that also faces housing deprivation defined by poor amenities such as a leaking roof, lacking sanitation facilities (bath, shower, indoor flushing toilet) or a dwelling considered to be too dark. In 2020, 4.3 % of the EU population faced severe housing deprivation, a 1.0 percentage point improvement compared with 2015. Among people living in monetary poverty, 10.2 % were affected by this situation in 2020, compared with only 3.2 % of the richer population [13].

An analysis by degree of urbanisation reveals that city dwellers in particular are more likely to be overburdened by their housing costs. In 2020, 9.9 % of people living in cities spent 40 % or more of their household disposable income on housing, compared with only 7.0 % for towns and suburbs and 5.8 % for rural areas. Severe housing deprivation was similar in rural areas (4.9 %) and in cities (4.8 %) in 2020; in towns and suburbs the rate was 3.4 % in that year [14].

People most commonly report costs as the reason for unmet needs for medical care

Access to health care services is important for ensuring a high quality of life. In turn, this may contribute to increased productivity and reduced costs associated with social protection systems. Barriers to accessing health services include costs, distance and waiting time. In 2022, 2.2 % of the EU population aged 16 and above reported unmet needs for medical care. While this is an improvement of 1.3 percentage points compared with 2010, it also represents a 0.6 percentage point deterioration compared with 2017, when only 1.6 % of people had reported unmet needs for medical care. Thus, the short-term trend is negative. Cost was the main reason given for limited access to health care services, indicated by 1.1 % of the EU population in 2022. People with lower incomes face a much higher share of unmet needs for medical care. While only 0.3 % of the richest 20 % of the population reported unmet care needs due to financial constraints, 2.4 % of people in the poorest quintile reported that this was the case. Regarding differences between age groups, the prevalence of unmet needs for medical care was lowest among people aged 16 to 29 years, at 1.3 %, and it was highest for people aged 75 years or over, at 3.2 % [15].

Main indicators

Persons at risk of poverty or social exclusion

While a household's income is a key determinant of its standard of living, other aspects can prevent people from fully participating in society such as an impeded access to labour markets or material and social deprivation. To reflect these different dimensions of poverty or social exclusion, the indicator ‘at risk of poverty or social exclusion’ measures the number of people affected by at least one of the following three forms of poverty or social exclusion: monetary poverty (at-risk-of-poverty rate), severe material and social deprivation and very low work intensity. Data on the three components are derived from the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC).

Source: Eurostat (sdg_01_10)

Source: Eurostat (sdg_01_10)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_pees01n)

Source: Eurostat: (ilc_pees01n), (ilc_peps02n), (ilc_peps03n), (ilc_peps04n), (ilc_peps05n), (ilc_peps06n), (ilc_peps13n), (ilc_peps60n) and (hlth_dpe010)

Persons at risk of monetary poverty after social transfers

This indicator measures the number of people with an equivalised disposable income below the risk-of-poverty threshold. This is set at 60 % of the national median equivalised disposable income after social transfers [16]. The data stem from the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC).

Note: y-axis does not start at 0.

Source: Eurostat (sdg_01_20)

Source: Eurostat (sdg_01_20)

Severe material and social deprivation rate

The indicator shows an involuntary lack of necessary and desirable items to lead an adequate life. It is defined as the proportion of the population who cannot afford at least 7 of the following 13 deprivation items: (1) pay rent, utility bills, hire purchase instalments or other loan payments, (2) keep their home adequately warm, (3) face unexpected expenses, (4) eat meat, chicken, fish or vegetarian equivalent every second day, (5) a week of holiday away from home, (6) have access to a car/van for personal use, (7) replace worn-out furniture, (8) replace worn-out clothes with some new ones, (9) have two pairs of properly fitting shoes, (10) spend a small amount of money each week on themselves (‘pocket money’), (11) have regular leisure activities, (12) get together with friends/family for a drink/meal at least once a month, and (13) have an internet connection. Items 1 to 7 relate to the household level, while the remaining items 8 to 13 relate to the level of the individual. Data for this indicator stem from the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC).

Source: Eurostat (sdg_01_31)

Source: Eurostat (sdg_01_31)

Persons living in households with very low work intensity

This indicator describes the share of people aged less than 65 living in households where the working age adults aged 18 to 64 worked equal to or less than 20 % of their total combined potential work-time during the previous year. It excludes students aged 18 to 24 and people who are retired according to their self-defined current economic status or who receive any pension (except survivors pension), as well as people aged 60 to 64 who are inactive and live in a household where the main income comes from pensions (except survivors' pension). The EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) is the data source for this indicator.

Source: Eurostat (sdg_01_40)

Source: Eurostat (sdg_01_40)

In work at-risk-of-poverty rate

This indicator refers to the share of people aged 18 years or over who declare to be at work (employed or self-employed) and who are at risk of monetary poverty. People are considered ‘employed’ if they held a job for more than half of the reference year. Data for this indicator are taken from the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC).

Note: y-axis does not start at 0.

Source: Eurostat (sdg_01_41)

Source: Eurostat (sdg_01_41)

Housing cost overburden rate

The indicator reflects the share of the population living in households where the total housing costs ('net' of housing allowances) represent more than 40 % of the disposable income. This indicator is derived from the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC).

Source: Eurostat (sdg_01_50)

Source: Eurostat (sdg_01_50)

Direct access to

More detailed information on EU SDG indicators for monitoring of progress towards the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), such as indicator relevance, definitions, methodological notes, background and potential linkages can be found in the introduction as well as in Annex II of the publication ’Sustainable development in the European Union — Monitoring report on progress towards the SDGs in an EU context — 2024 edition’.

Further reading on poverty

- European Commission (2023), Employment and Social Developments in Europe Annual Review 2023, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

- European Commission (2024), Joint Employment Report 2024, Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, Brussels.

- European Commission (2017), European Semester Thematic Factsheet, Social Inclusion.

- European Parliament (2023), Factsheet, The fight against poverty, social exclusion and discrimination.

- European Union (2023), Social Protection Committee Annual Report 2023, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

- European Union (2021), Improving the understanding of poverty and social exclusion in Europe – 2021 edition, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

- United Nation (2023), The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023 Special Edition, United Nations Publications, New York.

Further data sources on no poverty

Notes

- ↑ In 2021, the AROPE indicator was modified and the new EU 2030 target was based on the revised definition. The ‘severe material deprivation’ indicator was replaced with the ‘severe material and social deprivation’ indicator also considering social aspects such as leisure activities and social relationships in addition to the material aspects of deprivation. In addition, the definition of ‘very low work intensity’ — referring to people living in (quasi-)jobless households — was adjusted, including extending the monitored age group from 0–59 to 0–64 years. As a consequence, the two components and thus the whole AROPE indicator presented in this report have indicator values from 2015 only and are not comparable with the data in reports before 2022.

- ↑ In 2020, the German EU-SILC survey, on which the AROPE indicator is based, was integrated into the newly designed German microcensus, leading to a substantial break in the time series between 2019 and 2020, with income variables being the most affected by the break. For more information see the related information note. In addition to the (ilc_peps01n) table used for AROPE and its intersections, the break-free estimates of AROPE from 2019 (available in the dataset (ilc_pecs01)) can be used for the purpose of assessing the overall progress towards the 2030 poverty and social exclusion target. In addition to Germany, further countries such as France also reported methodological changes in 2020, which also affected the EU total.

- ↑ Variables related to income (only) in the indicators at-risk-of-poverty rate and the people living in households with very low work intensity indicator, refer to the income reference period (N-1), which in EU-SILC corresponds to the previous year of the survey. Please note that both indicators involve other variables not related to the survey year (N). The indicator ‘severe materially or socially deprived’ does not involve any income-related variables. The EU-SILC indicators provide insights on the economic well-being and other living conditions on EU residents based on data collected during a specific year, denoted as N. This data encompasses both the characteristics of households for that year (N) and the income from the preceding year, N-1. The income for year N-1 is an estimate for income of year N within EU-SILC.

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (ilc_li10)).

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (tespm050)).

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (ilc_peps01n)).

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data codes: (tepsr_spi110), (tepsr_spi120) and (tepsr_spi130)).

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (ilc_peps60n)).

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (ilc_peps03n)).

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data codes: (ilc_peps02n), (ilc_peps05n), (ilc_peps06n), (hlth_dpe010), (ilc_peps04n), (ilc_peps13n) and (ilc_peps01n)). Further information on vulnerable groups particularly at risk of poverty or social exclusion can be found on Eurostat’s Statistics Explained pages related to ‘Poverty and social exclusion’.

- ↑ European Commission (2023), Joint Employment Report 2024, Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, Brussels.

- ↑ A household is considered overcrowded if it does not have at least one room for the entire household as well as a room for a couple, for each single person above 18, for a pair of teenagers (12 to 17 years of age) of the same sex, for each teenager of different sex and for a pair of children (under 12 years of age).

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (ilc_mdho06a)).

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data codes: (ilc_lvho07d) and (ilc_mdho06d)).

- ↑ Source: Eurostat (online data code: (hlth_silc_08)).

- ↑ The equivalised disposable income is the total income of a household, after tax and other deductions, that is available for spending or saving, divided by the number of household members converted into equalised adults; household members are equalised or made equivalent by weighting each according to their age, using the so-called modified OECD equivalence scale.