Archive:Hours of work and absences from work - quarterly statistics

Data extracted in February 2021

Planned article update: April 2022

Highlights

This article aims to describe the quarterly change in the hours actually worked by employed people in their main job in the first three quarters of 2021 in the European Union (EU) as a whole, for all EU Member States individually, as well as for three EFTA countries (Iceland, Norway and Switzerland) and one candidate country (Serbia).

Statistics on the volume of working hours provides an economic perspective to employment as it represents an estimate for the labour input to the production. Reporting on quarterly data allows for a short-term assessment of shocks on the working life and economy.

Results presented in this article come from the EU Labour Force Survey (LFS). Since the first quarter of 2021, all countries participating in the survey have harmonised their questionnaire with regard to the collection of the working hours; this information is consequently collected in the same way in all countries, ensuring enhanced comparability and quality of the results.

This article is part of the online publication Labour market in the light of the COVID-19 pandemic - quarterly statistics.

Full article

Differences in the length of the actual working week

In the EU, during the third quarter of 2021, employed people, aged 20-64, spent in work 37.0 hours on average per week. This number is 0.8 hours higher when compared with the previous quarter. These numbers refer to the hours people have actually spent in work activities in the main job during the surveyed reference week. Note that the "actual hours of work" can differ from the "usual hours of work", which are the modal value of the actual hours worked per week over a long reference period (one to three months), excluding weeks when an absence from work occurs (e.g. holidays, leaves, strikes, etc.).

The EU average of the actual working hours per week hides many differences among countries (see Map 1). The longest weeks of work among the EU Member States, of 39.5 hours or more, were found in Bulgaria (39.9 hours), Romania (40.2 hours), Poland (40.8 hours) and Greece (41.6 hours). However, even a longer working week was found outside the EU, namely in Serbia, with 43.4 hours of work on average. In contrast, the shortest weeks, of less than 35.5 working hours, were observed in Belgium (35.1 hours), Germany (35.0 hours), Austria (34.7 hours) and the Netherlands (32.6 hours). The EFTA country Norway (34.9 hours) also stands out with a relatively short working week.

Map 1 reveals a clear geographical pattern in the length of the average working week, as the Eastern and Southern countries tend to have more hours of work per week than the Western and Northern countries.

Note, however, that the presented average is computed as the total number of actual hours of work divided by the number of employed people having actually worked, i.e. not including people absent from work (for holidays, sickness, temporary lay-off, etc.). If people absent from work are also taken into account in the average, the denominator will be higher while the numerator will remain the same, leading to a considerably lower average when people absent from work are numerous.

It is also worth noting that the average working hours presented in this article include both people working full and part-time. It could be expected that countries with a high share of part-time workers would report shorter average working week for the total employed population. Indeed, the Netherlands, Austria, Germany and Belgium had the shortest average working week while having the highest shares of part-time workers in the EU during Q3 2021. More information on part-time workers can be found in the article on employment.

Perspective into full and part-time workers

The length of the average working week of full-time workers in the EU ranged from 43.3 hours in Greece to 38.3 hours in Slovakia (see Figure 1 A.). The candidate country Serbia (44.8 hours) and the EFTA Switzerland (43.4 hours), however, surpassed Greece with even longer working weeks for full-time workers. The longest working week for part-time workers, amounting to 28.6 hours, was found in Romania, while the shortest, of 18.8 hours, was recorded in Portugal. Note that in the vast majority of countries, the length of the average working week of part-time workers was around half the length of the working week of full-timers. Nonetheless, there were some exceptions. The most obvious example can be seen in Romania where the average working hours per week of full and part-time workers is relatively close (40.6 hours compared with 28.6 hours).

Source: Eurostat (lfsq_ewhan2)

Looking at the gender differences (Figure 1 B.), in all countries, men full-timers worked more hours per week than their female counterparts. The most significant difference among the EU Member States was recorded in Ireland, as the average working week for male full-timers in this country consisted of 41.5 hours, compared with 37.5 hours for women working full-time. The gender pattern is not so conclusive regarding employed on part-time: in some countries, women had longer working weeks in some countries was the opposite. Denmark stood out with the largest difference in the length of the average working week between men and women part-timers - 19.1 versus 22.8 hours.

How the average working week varies across sectors of the economy and groups of occupations?

The length of the average working week measured in numbers of actual hours of work varies across different sectors of the economy (NACE Rev. 2), as revealed in Figure 2 (EU level). In Q3 2020, employed people in sector agriculture, forestry and fishing spent the largest number of hours at work - 43.6 hours on average per week. This sector was followed by the sectors mining and quarrying (40.3 hours), construction (40.0 hours) and transportation and storage (39.0 hours), where the average working week of employed people was also relatively long. In contrast, workers in administrative and support service activities (33.9 hours), education (32.5 hours) and activities of households as employers (26.8 hours) had the shortest average working weeks.

Source: Eurostat (lfsq_ewhan2)

Looking at the different groups of occupations (ISCO-08), the skilled agricultural, forestry and fishery workers (44.7 hours) and the managers (42.4 hours) stood out with the longest average working weeks in the EU during Q3 2021 (see Figure 3). On the other end of the ranking, the clerical support workers (34.6 hours) and workers having elementary occupations (32.4 hours) had the shortest working weeks.

Source: Eurostat (lfsq_ewhais)

Impact of COVID-19 pandemic and potential recovery

The previous section of the article explored the number of hours each employed person had spent in work on average per week. The focus in this section is the development of the total number (volume) of actual working hours in the main job, i.e. the sum of hours each worker devoted to labour in the main job. To capture better the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the volume of working hours, the values for all quarters from Q1 2019 to Q3 2021 were indexed to the average for the pre-pandemic year 2019 (=100).

At EU level, the total number of actual working hours decreased by 5 index points (henceforth called only points) from Q4 2019 to Q1 2020 and reached 97 points (see Figure 4). The change from Q1 to Q2 2020 was much more drastic, amounting to an 11 points decrease. As a result, the volume of actual working hours fall to 86 points in Q2 2020, the lowest value for the observed period (Q1 2019 - Q3 2021). In the following quarters, the index of working hours started an upward trend, reaching 93 points in Q3 2020, stabilizing at 96 points in Q4 2020 and Q1 2021 and increasing to 99 points in Q2 2021. In Q3 2021, the index dropped to 93 points, however, should be kept in mind that the decline in the number of hours between Q2 and Q3 2021 might be of a seasonal nature given that Q3 2021 coincides with the summer period of the year and a similar decrease can be observed between Q2 and Q3 2019.

With respect to the year-on-year development, the volume of actual working hours in Q1 2021 was 1 point below its level in Q1 2020 and 6 points below the level recorded in Q1 2019. In Q2 2021, the volume was 13 points above Q2 2020, but still 2 points below Q2 2019. Finally, the volume of working hours in Q3 2021 is around the same level as in Q3 2020, but 2 points below Q3 2019.

The comparison between men and women in terms of the development of the total number of working hours does not show a substantial difference. However, it appears that in 2021 the index of working hours reached its base value of 100 only for women (in Q2 2021), following a couple of quarters with a slightly stronger increase for women than for men.

Employees less affected than self-employed

The breakdown by professional status holds significantly more differences between its categories. As shown in Figure 5, self-employed with employees (employers) and self-employed without employees (own-account workers) experienced a much stronger decrease in the total number of hours during 2020 and 2021 in comparison with employees. In Q2 2020, the quarter which was the most severely affected by the pandemic, the index of working hours for employees dropped to 87 points, whereas it decreased to 80 points for own-account workers and to 79 points for employers. Moreover, after Q2 2020, the index of working hours for employees had a steady upward trend until Q2 2021 when it reached its base value of 100; while at the same time the development for the two groups of self-employed people was marked by a decrease in some of the quarters. From Q2 2021 to Q3 2021, the index of working hours decreased to 94 points for employees and to 92 points for own-account workers, while it remained stable at 96 points for employers.

If we compare the most recent quarter shown in this article, i.e. Q3 2021, with the third quarter in 2020 and 2019, it appears that the volume of working hours for employees in Q3 2021 was at around the same level as in the previous two years (no more than a 1 point difference of the index). The index of working hours for employers, on the other hand, showed no change between Q3 2021 and Q3 2019; however, it was 6 points higher in Q3 2021 if we compare it with Q3 2020. In contrast, the index for own-account workers in Q3 2021 was 3 points below Q3 2020 and 6 points below Q3 2019.

People aged 55-64 less affected than younger age groups

When it comes to the quarterly development of the volume of working hours, it appears that age plays a significant role. Young people aged 15-24 experienced a much sharper cut in the total number of working hours during 2020 and 2021 compared with people aged 25-54, and people aged 25-54, from their side, had a much sharper cut than people in the senior age group 55-64 (see Figure 6). This difference is the most pronounced in Q2 2020, when the index of working hours for young people decreased to 78 points, while for people aged 25-54 decreased to 86 points, and for those falling in the age category 55-64 to 90 points. Also, in Q1 2021, the index for people aged 15-24 amounted to 88 points, whereas it was 96 points for those aged 25-54 and 101 points for aged 55-64. In addition to that, after the lowest point of the volume of working hours in Q2 2020, the recovery for people aged 25-54 and 55-64 was more direct, showing an uninterrupted increase in the number of working hours until Q3 2021. Moreover, age group 55-64 had an index equal to or above the base value (2019=100) in Q4 2020, Q1 and Q2 2021. At the same time, the recovery for people aged 15-24 was marked by some fluctuations; namely a decrease in the number of working hours in Q4 2020 and Q1 2021.

When comparing different age groups, another particularity occurs: in Q3 2019 and Q3 2021, young people had a stronger increase in the volume of working hours than the other age groups. A possible explanation for this phenomenon might be the increase of seasonal work for young people during the summer months, which correspond to the third quarter of each year. At the same time, one might expect that the older age groups usually take holidays during the summer, which might explain the reduction of hours for people aged 25-54 and 55-64 in Q3 2019 and Q3 2021. A similar pattern can be also seen in Q3 2020; however, in this particular quarter, people aged 55-64 had a stronger increase in the volume of working hours than young people.

The volume of working hours for young people in Q3 2021 was 5 points above the level a year ago (Q3 2020), however, 3 points below the level in Q3 2019. The volume of working hours for people aged 25-54 in Q3 2021 was at around the same level as in Q3 2020; however, it was 3 points below the level in Q3 2019. Finally, the seniors (aged 55-64) had a higher number of total working hours in Q3 2021 when compared with Q3 2020 (+2 points) and Q3 2019 (+3 points).

Six EU countries had a larger volume of working hours in Q3 2021 than in Q3 2019

Shifting the focus on country-level data (Figure 7, total population aged 20-64), 15 EU Member States registered an increase in the volume of working hours from Q3 2020 to Q3 2021, however, only six of them also registered an increase when Q3 2021 is compared with Q3 2019, namely Belgium, Cyprus, France, Slovenia, Denmark and Poland. No other EU country than the aforementioned six registered an increase from Q3 2019 to Q3 2021. Please, note that as the single quarter Q3 2021 is compared with Q3 in 2020 and 2019, Figure 7 presents not an index but a percentage change difference. Belgium stood out with the highest increase in Q3 2021, amounting to +7 % when compared with Q3 2020 and +6 % when compared with Q3 2019. In contrast, 11 EU countries had a decrease in the volume of working hours in Q3 2021 compared with Q3 2020; all of them also recorded a decrease when compared with Q3 2019. Among these countries, the largest cuts were found in Estonia (-8 % compared with both Q3 2019 and Q3 2020) and Luxembourg (-7 % compared with Q3 2019 and -8 % compared with Q3 2020). Latvia and Romania also experienced a relatively large decrease in the volume of working hours in Q3 2021, both countries -5 % when compared with Q3 2020 and -9 % when compared with Q3 2019.

Impact of absences from work

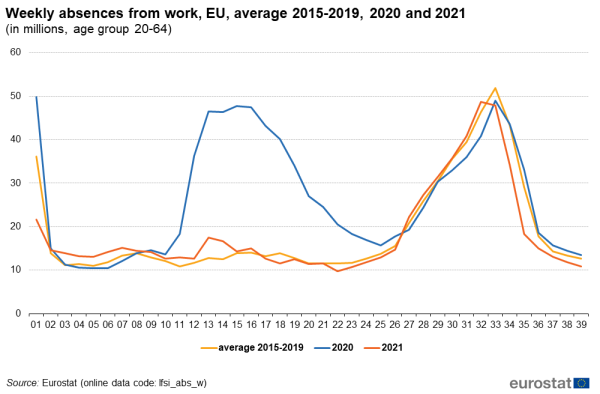

One of the key determinants of the total volume of hours worked is the level of absences from work. As can be seen in Figure 8, the number of weekly absences in weeks 11 to 26 during 2020 (end of Q1 2020 and entire Q2 2020) is substantially higher than the average number of absences in the respective weeks in 2015-2019. At the same time, i.e. Q2 2020, the volume of working hours had its most significant decline.

Source: Eurostat (lfsi_abs_w)

Although due to a break in time series, data for 2021 are not fully comparable with the previous years, is visible that the number of absences is closer to the average 2015-2019 than to 2020. Still, it can be noticed that the number of absences from week 2 to week 16 in 2021 exceeds the average 2015-2019, especially in weeks 13 and 14. During the following period, weeks 17 to 32 2021, absences gravitate around the average 2015-2019, and during weeks 33 to 39 2021, the number of absences is below the average 2015-2019.

The last figure of this article (Figure 9) shows a country overview of the absences from work on a quarterly basis. To facilitate the international comparison, the number of absent from work people is expressed as a percentage of the employed population in each country.

Looking at the development of the percentage of absences in 2021 a couple of patterns can be discerned. Firstly, in 7 EU Member States (the Netherlands, Estonia, Sweden, Finland, Belgium, Luxembourg and France), this share increased consecutively from Q1 to Q2 and then from Q2 to Q3, nonetheless, the increase between the first two quarters was substantially milder than the increase between the second and third. On the other hand, the majority of EU countries (the remaining 20), experienced a decrease in the share of absences from work from Q1 to Q2 but an increase from Q2 to Q3.

Another pattern is that in most of the Member States (22 countries) the share of absences takes its highest values in Q3 2021. This, however, was not the case in five EU countries - Bulgaria, Latvia, Ireland, Slovakia and Greece - where people absent from work represented a higher percentage of employment in Q1 2021 than in the following two quarters of 2021.

Another relevant finding is that despite the variations of the share of absences in 2021, Bulgaria and Romania were always at the bottom of the scale with the lowest shares in the EU (never exceeding 4 %).

There is also a certain repetition of countries with the highest rates of absences in 2021. In Q1, these were Ireland (20.0 %), Greece (18.1 %) and Slovakia (15.7 %). In the following quarter (Q2), Finland (13.5 %), Ireland (13.4 %) and France (12.0 %), and in Q3 - Sweden (27.8 %), France (23.6 %) and Finland (22.7 %). Sweden is also worth mentioning with the sharpest quarter-on-quarter increase of the share of absences, amounting to +17.2 percentage points between Q2 and Q3 2021.

In addition to the level of absences from work, the level of employment also influences the volume of working hours. Further information on the employment situation in 2021 can be found in the quarterly articles on employment and employed people and job starters by economic activity and occupation.

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

All figures in this article are based on quarterly results from the European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS).

Source: The European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS) is the largest European household sample survey providing mostly quarterly and annual results on labour participation of people aged 15 and over as well as on persons outside the labour force. It covers residents in private households. Conscripts in military or community service are not included in the results. The EU-LFS is based on the same target populations and uses the same definitions in all countries, which means that the results are comparable between countries.

European aggregates: EU refers to the sum of the EU-27 Member States. If data is unavailable for a country, the calculation of the corresponding aggregates is computed with estimates. Such cases are indicated.

Country note: Spain and France have assessed the attachment to the job and included in employment those who have an unknown duration of absence but expect to return to the same job once the COVID-19 measures in place are lifted.

Eight different articles on detailed technical and methodological information are available from the overview page of the online publication EU Labour Force Survey. Detailed information on coding lists, explanatory notes and classifications used over time can be found under documentation.

Main methodological changes introduced by Regulation (EU) 2019/1700

- persons on parental leave, and who are either receiving job-related income or benefits, or whose parental leave is expected to last 3 months or less, are counted as employed;

- persons raising agricultural products for own-consumption are excluded from employment;

- seasonal workers outside the season are classified as employed if they still regularly perform tasks and duties for the job or business during the off-season;

- people with a job or business who were temporarily not at work during the reference week but with strong attachment to their job are still considered as employed. In the particular context of the COVID-19 crisis and the measures applied to combat it, national specificities exist in the assessment of the job attachment;

- not employed people are considered searching for a job only if they use an active search method;

- further harmonisation in the implementation of questions and modernisation of the survey at national level.

Insofar most of these changes are related to the classification as employed or not of people who are absent from work who as such are not producing any hours of work anyway, the impact of the methodological changes on the volume of working hours is assumed as milder.

Context

The COVID-19 pandemic hit Europe in January and February 2020, with the first cases confirmed in Spain, France and Italy. COVID-19 infections have been diagnosed since then in all European Union (EU) Member States. To fight the pandemic, EU Member States have taken a wide variety of measures. From the second week of March 2020, most countries closed retail shops, with the exception of supermarkets, pharmacies and banks. Bars, restaurants and hotels were also closed. In Italy and Spain, non-essential production was stopped and several countries imposed regional or even national lock-down measures which further stifled economic activities in many areas. In addition, schools were closed, public events were cancelled and private gatherings (with numbers of persons varying from 2 to over 50) banned in most EU Member States.

The majority of the preventive measures were initially introduced during mid-March 2020. Consequently, the first quarter of 2020 was the first quarter in which the labour market across the EU was affected by COVID-19 measures taken by the Member States.

In the following quarters of 2020 and 2021, the preventive measures against the pandemic were continuously lightened and re-enforced in accordance with the number of new cases of the disease. New waves of the pandemic began to appear regularly (e.g. peaks in October-November 2020 and March-April 2021). Furthermore, new strains of the virus with increased transmissibility emerged in late 2020, which additionally alarmed the health authorities. Nonetheless, as massive vaccination campaigns started all around the world in 2021, people began to anticipate improvement of the situation regarding the COVID-19 pandemic.

Statistics on the hours of work add a new dimension to employment. The “average number of actual weekly hours of work in the main job” is an indicator aiming to give a perspective to the social conditions of labour, while the volume of hours worked adds an economic perspective, insofar as it serves as a proxy for the labour input to the production. The quarterly data on hours of work allows to regularly report on the impact of the crisis due to the COVID-19 pandemic on the working life and economy.

Please note that in this exceptional context of the COVID-19 pandemic, employment and unemployment as defined by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) might not be sufficient to describe the developments taking place in the labour market. In the first phase of the crisis, active measures to contain employment losses led to absences from work rather than dismissals, and individuals could not look for work or were not available due to the containment measures, thus not counting as unemployed. Only referring to unemployment might consequently underestimate the entire unmet demand for employment, also called the labour market slack, which is further analysed, with namely the evolution of the employment and the recent job starters, in the publication Labour market in the light of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Direct access to

See also

Main tables

Database

Dedicated section

Publications

- Labour force survey in the EU, EFTA, United Kingdom and candidate countries — Main characteristics of national surveys, 2019, 2021 edition

- Quality report of the European Union Labour Force Survey 2019, 2021 edition

- Labour market in the light of the COVID 19 pandemic — online publication

- EU labour force survey — online publication

- European Union Labour force survey - selection of articles (Statistics Explained)

Methodology

Publications

- EU labour force survey — online publication

- Labour force survey in the EU, EFTA, United Kingdom and candidate countries — Main characteristics of national surveys, 2019, 2021 edition

- Quality report of the European Union Labour Force Survey 2019, 2021 edition

ESMS metadata files and EU-LFS methodology

- Employment and unemployment (Labour Force Survey) (ESMS metadata file — employ_esms)

- LFS series - detailed quarterly survey results (from 1998 onwards) (ESMS metadata file — lfsq_esms)

- LFS series - detailed annual survey results (ESMS metadata file — lfsa_esms)

- LFS ad-hoc modules (ESMS metadata file — lfso_esms)

- LFS main indicators (ESMS metadata file — lfsi_esms)

- LFS regional series (ESMS metadata file — reg_lmk)