Archive:Sample size and non-response - quarterly statistics

Data extracted in January 2021

Planned article update: April 2021

Highlights

The global spread of Sars-CoV-2 at the beginning of 2020 has had a lasting impact on large parts of the public and private life. Due to many government-imposed restrictions to contain the pandemic, the working lives of the citizens in the EU have changed enormously. At times, kindergartens, schools, stores and businesses were completely closed in most countries due to a hard. Wherever possible, and employees working from home.

This has affected the EU-LFS in two ways. Firstly, the working reality of many people has changed extensively, so that 2020 EU-LFS data may show significant differences from previous year's figures. Secondly, data may also contain random and systematic errors. Distinguishing actual changes in the labour force from survey errors is quite complicated.

In this context, this article assesses the quality of the data gathered through the EU-LFS for the European Union (EU) as a whole, for each EU Member State individually, as well as for three EFTA countries (Iceland, Norway and Switzerland), the United Kingdom and four candidate countries (Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia and Turkey). The analysis is based on data and information available up to 13 January 2021. Data for the three quarters of 2020 is mainly compared with data for the same quarters of 2019 (for sample size and sampling errors) in order to avoid comparability issues and bias due to seasonality. Regarding unit non-response, a comparison with annual averages for previous years is also included. Please note that this procedure is legitimate since unit non-response is usually not particularly affected by seasonality and therefore quite stable throughout the year.

This article is part of the online publication Labour market in the light of the COVID-19 pandemic - quarterly statistics.

Full article

Drastic increase in the unit non-response rate in 2020

The unit non-response occurs when no data are collected about a population unit (usually a person or a household) designated for data collection. Consequently, the unit non-response rate is the ratio of the number of units for which data has not been collected to the total number of units designated for data collection (sampling frame).

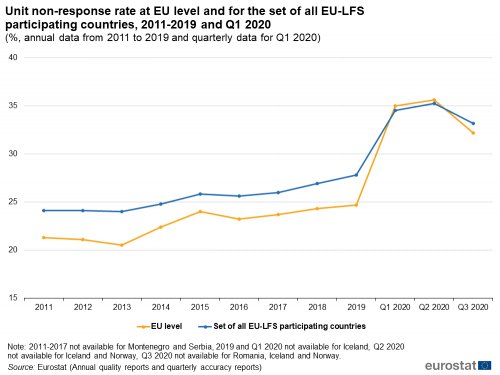

Since the beginning of the time series (2011), the unit non-response rate smoothly increased at EU level (see Figure 1). The same conclusion can be drawn when all countries carrying out the European Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS) are considered. However, between the year 2019 and the second quarter of 2020, the unit non-response rate sharply increased at EU level due to the lockdown measures adopted by most Member States to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic: from 24.7 % in 2019 to 35.0 % in Q1 2020 and 35.6 % in Q2 2020 (over than ten percentage points). Face-to-face (CAPI (Computer Assisted Personal Interviewing) and PAPI (Paper and Pencil Interviewing)) data collection methods have been stopped and replaced as much as possible by remote collection methods (CATI (Computer Assisted Telephone Interviewing) or CAWI (Computer Assisted Web Interviewing)). Unit non-response mainly increased due to phone numbers or email addresses that were not always immediately available. In Q3 2020 confinement measures have been partly lifted in all member states so data collection returned to the usual methodology and non-response declined to 32.2 %.

Note: 2011-2017 not available for Montenegro and Serbia, 2019 and Q1 2020 not available for Iceland, Q2 2020 not available for Iceland and Norway, Q3 2020 not available for Romania, Iceland and Norway.

Source: Eurostat (Annual quality reports and quarterly accuracy reports)

Even if a sharp increase between the year 2019 and the first three quarters of 2020 can be seen at EU level, the situation is quite different across countries. In Bulgaria, Ireland, France, Latvia, Hungary, Portugal, Slovenia, the United Kingdom and Serbia the unit non-response rate increased by around 10 percentage points and more in Q2 2020 (see Figure 2). Belgium, Czechia, Greece, Spain, Italy, Lithuania, Romania and Turkey also recorded a significant rise in their unit non-response rate (rise between 4.5 p.p. and 6.7 p.p.). In Q3 2020 non-response rate in many countries compared with the first two quarter of 2020 even though in some countries it raised again as in Belgium, Ireland, Greece, the United Kingdom and Turkey. A case apart is represented by Germany who scores a non-response rate around 50% in the whole 2020, but this is also related to the introduction of the new survey under the new regulation and it is not possible to separate the effect of the pandemic from that one due to the change in the methodology. All the countries that report higher non-response broadly used face-to-face interviewing techniques (CAPI and PAPI) for the EU-LFS data collection. By contrast, countries relying exclusively on CATI and CAWI techniques did not perceive a big impact on their unit non-response rate between the year 2019 and 2020 as well as Denmark, Finland, Sweden and Switzerland.

Starting from 2020 , Eurostat is collecting quarterly data on survey mode used by countries to carry out the survey while previously only on annual basis data on survey mode was available. For the first three quarters of 2020 EU data is available except for Czechia, Denmark, Germany, France, the Netherlands, Romania and Slovenia. The impact of the pandemic on LFS data collection is reported in Figure 3 about the distribution of interviews by survey mode. Indeed in 2020 remote interviewing modes (CATI and CAWI) increased, in particular in Q2 and Q3 2020 where CATI scored on average more than 10 pp. compared with the previous years and CAWI reached 3% from less than 1% previously. Moreover “other” methods that reached the peak in Q2 2020 (8.8 %) and most of time consist in interviews copied from previous waves (only for people aged 75 and more outside the labour force) in previous years was accounted to the mode used for the first interview.

Note: data for Czechia, Denmark, Germany, France, the Netherlands Romania and Slovenia is not available.

Source: Eurostat (Annual quality reports and specific calculations on microdata)

<sesection>

Sample size decreased over the first three quarters of 2020

The EU-LFS is based on the uniform sample distribution of the quarterly sample over all the reference weeks of the quarter. This means that the size of each weekly sample corresponds to the size of the total quarterly sample divided by the number of weeks in the quarter (generally 13). The achieved sample size in 2020 is generally lower than in 2019. The distribution of the weekly difference in the collected sample between both years is on average around 3 500 individuals (see Figure 4) for a total situated around 67 000 in 2019 compared with more than 70 000 individuals in 2020. In Q1 2020, the difference between the two years increased to 9 000 in week 10, and even to 11 000 in weeks 11 and 12. In week 13, the difference between the two years narrowed to around 4 000 individuals. These numbers reflect the lockdown measures taken by the governments of several EU Member States in the first quarter of 2020 from week 10 onwards. The achieved sample size shows a decrease from week 10 due to restrictions in surveys data collection. Then, after countries adopted measures to increase the survey participation (like the use of additional information to reach people selected in the sample: such as telephone numbers or email addresses from registers of mobile phone or landlines numbers and tax databases), the achieved sample size increased again. Indeed in Q2 2020, the difference in week 7 disappeared and in the two following weeks sample size in 2020 was over than 2019 of around 2 000 individuals but, from week 10 it was back to be under the previous year of about 2000 individuals till the end of the quarter. In quarter 3 2020, differences continuously decreased from the beginning (2020 lower than 2019 of about 6 000 individuals) up to week 9 when 2020 reached the same levels of 2019 but in week 10 it fell again to a gap of 8 000 individuals. Only in week 13 difference between 2020 and 2019 drop to around 2 000 individuals. Due to the changes in the LFS methodology in 2020, Germany and France are not included in the EU aggregate.

At EU level, the ratio of the average weekly number of people interviewed in Q3 2020 was 94.4 % with regard to the same quarter of 2019 (see Figure 5). In the whole 2020 the average weekly sample size was lower than 2019; indeed also in Q1 and Q2 it was 93.7 % and 96.4 % respectively in comparison of the same quarters of the previous year. In the first quarter of 2020, at the beginning of the pandemic, almost all countries reported a reduction in the sample size collected compared with the same quarter of the previous year. Only five EU Member States (Belgium, Estonia, Malta, Austria and Sweden) had a bigger average weekly sample in Q1 2020 compared with Q1 2019 as well as in Q2 2020 six countries (Estonia, Luxembourg, Hungary, Austria, Polonia and Sweden). In Q3 2020 more countries were able to return to a sample size closer to the situation in 2019. The situation was particularly critical in Lithuania, where the ratio of the average weekly sample size in Q1 and Q3 2020 was around 80 % than in the same quarters of 2019 as well as for Portugal in Q2 and Q3. In Q3 2020 also Hungary, Bulgaria Denmark Ireland and Latvia recorded an average weekly sample size less than 90% compared with Q3 2019.

Slight increase in sampling errors in figures for the first two quarters of 2020

The estimates produced by the EU-LFS are subjected to specific precision requirements specified in the Council Regulation (EC) No 577/1998, which establishes the organisation of the survey. In particular, specific requirements are defined concerning the reliability of estimates on the number of employed and unemployed. The coefficient of variation (CV) for the employed and unemployed population, as an indicator of the precision of the EU-LFS estimates, is transmitted by countries to Eurostat on a quarterly basis.

As can be seen from Figure 6, the COVID-19 crisis also had an impact on the precision of the measurement of employment and unemployment. Fourteen EU countries reported a deterioration in the accuracy of the estimates for both employment and unemployment between the first quarter of 2019 and the first quarter of 2020. In addition, other seven countries showed deterioration only for unemployment figures and one for employment. This deterioration is linked to the continuous increase in the unit non-response (already visible in previous years), which reduces the achieved sample size, especially in the specific segment of the population attached to the labour market, and also to an additional increase in greater intensity coming from the COVID outbreak. The situation improved during Q2 2020 where ten countries had a worse precision for both indicators compared with Q2 2019 and other ten countries only on employment estimates. In Q3 2020 only five countries shoved a fall of the precision for both estimates and eleven only for employment; on the contrary in 20 countries the quality of unemployment estimates improved compared with regard to Q3 2019.

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

All figures in this article are based on quarterly results from the European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS).

Source: The European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS) is the largest European household sample survey providing quarterly and annual results on labour participation of people aged 15 and over as well as on persons outside the labour force. It covers residents in private households. Conscripts in military or community service are not included in the results. The EU-LFS is based on the same target populations and uses the same definitions in all countries, which means that the results are comparable between countries.

European aggregates: EU refers to the sum of EU-27 Member States. If data is unavailable for a country, the calculation of the corresponding aggregates takes into account the data for the same country for the most recent period available. Such cases are indicated.

Country note: Due to technical issues with the introduction of the new German system of integrated household surveys, including the Labour Force Survey (LFS), the figures for Germany for the first and second quarter of 2020 are not direct estimates from LFS microdata, but based on a larger sample including additional data from other integrated household surveys. A restricted set of indicators has been estimated and used for the production of the LFS Main Indicators. These estimates have also been used in the calculation of EU and EA aggregates, and are published for some selected indicators (estimates for Germany are flagged as p – provisional, and u – unreliable). For more information, see here.

Definitions: The concepts and definitions used in the EU-LFS follow the guidelines of the International Labour Organisation.

Data collection techniques: The different kinds of data collection techniques used in the LFS are the following:

1) PAPI (Paper and Pencil Interviewing): PAPI is a face-to-face interviewing technique in which the interviewer enters the responses into a paper questionnaire. If no interviewer is present and respondents enter the answers themselves it is considered a self-administered questionnaire.

2) CAPI (Computer Assisted Personal Interviewing): CAPI is a face-to-face interviewing technique in which the interviewer uses a computer to administer the questionnaire. Responses are directly entered into the application, and control and editing can be directly performed.

3) CATI (Computer Assisted Telephone Interviewing): CATI is a telephone surveying technique in which the interviewer follows a questionnaire displayed on a screen. Responses are directly entered into the application. It is a structured system of interviewing that speeds up the collection, control and editing of information collected.

4) CAWI (Computer Assisted Web Interviewing): CAWI is an Internet surveying technique in which respondents follow a questionnaire provided on a website and enter the responses into the application themselves

Five different articles on detailed technical and methodological information are linked from the overview page of the online publication EU Labour Force Survey.

Methodological note on Survey Errors: The classical test theory provides a mathematical-statistical measurement model that links the theoretical construct (the attribute to be measured) with the measurement instrument (value measured by indicator/ item). It assumes that hypothetically there is a ‘true’ value of a person (e.g. the number of working hours). However, the value measured in the EU-LFS or the response reaction in the interview can be distorted by random and systematic errors and thus sometimes does not correspond to the actual attribute of the respondent. In methodological research, random errors are assumed to be rather unproblematic, since they balance each other out if the number of measurements (or respondents) is sufficiently large. Since systematic errors are all biased in the same direction, they cannot be compensated for and accordingly pose a serious problem for survey research. For this reason, since the establishment of survey methodology, there have also been research approaches that deal with the measurement of characteristics and the errors that occur in the process. In the concept of the Total Survey Error (TSE), all potential causes of errors in surveys were considered in one model. It describes and examines errors that can occur in the planning and implementation of the interview. Thus, the causes of bias (systematic errors) and variance (random errors) of the data in surveys are considered in one model. Usually, types of errors are divided into observational errors (measurement errors) and non-observational errors (errors of representation). The latter are a result from mistakes made by defining the inferential and target population and the sampling frame (coverage error), mistakes in the process of sampling households or individuals (sampling error) and errors due to the fact that not all sampled units are interviewed (non-response error). Observational errors regard mistakes made in the process of defining the construct that is to be measured (validity), the measurement process (measurement errors, due to characteristics of the measurement instrument, e.g. survey mode or questionnaire; the respondent, the interviewer or the interview situation) and the lack of compliance between the response given by the interviewee and the value recorded in the edited dataset (processing errors). Because of the many restrictions implemented by the governmentchanges to the survey mode might have been implemented by some countries. Changes of the data collection mode is always a sensitive issue, especially for research done with panel data or time series. Although, the most impact can be expected for non-factual questions (e.g. attitude items), the EU-LFS data could be biased as well. Every mode has very specific characteristics (e.g. interviewer present, visual or audial perception, cognitive burden, support and motivation opportunities, social desirability) that can result in different errors (sampling and non-sampling errors). Moreover, a change of the mode requires the programming or preparing of the questionnaire in another IT system. Because the pandemic came rather unexpected, there might not have been much time for pre-testing the survey in the new system, which could be another possible error source (e.g. wrong filtering). In addition, sampling errors could occur because certain people typically participate in specific modes. Thus, sampling errors might not only be related to obvious, recorded socio-economic characteristics of the respondents like sex, age and education, but also to characteristics not measured (e.g. personality traits, attitudes). As can be expected, the COVID-19 crisis mostly affected countries carrying out face-to-face interviews. Preliminary data showed that countries using only telephone (CATI) or telephone and online interviews (CATI and CAWI) were not effected in terms of an obvious mode impact (e.g. Denmark, Luxemburg, Finland). In contrast, countries who had to change the data collection from face-to-face modes (CAPI or PAPI with interviewer) to telephone or self-administered modes (CATI, CAWI or postal PAPI without interviewer) could have measurement errors in their EU-LFS 2020 data. When changing a mode from an interviewer-administered survey (CAPI or PAPI) to a self-administered one (PAPI or CAWI), the absence of the interviewer, who usually helps, guides and motivates the respondents, could cause errors. For example, the filter path could be done incorrectly, questions could be misunderstood, and selected units might not want to participate or might not answer all questions (nonresponse and item-nonresponse rates). Changes from face-to-face interviewing (CAPI or PAPI) to telephone interviewing (CATI) could also have an impact on the quality of the data. Although there is still an interviewer that leads the respondent through the survey, the absence of visual aids might add cognitive burdens for the interviewees, which can result in measurement errors. Lower motivation, invalid answers for proxy interview questions, higher nonresponse and item-nonresponse rates might have occurred. A change of the survey mode might also imply that, in case of closure of the CATI call centers, the interviews are conducted by the interviewers of the CAPI network in telephone mode, if telephone numbers are available, using their personal telephone and the CAPI software currently installed on the interviewers’ laptops and this would be also an additional source of bias. The higher ‘distance’ of the interviewer and the respondent in CATI compared with a face-to-face interview can have positive and negative effects. Households or people participating for the first time (1st wave) could have less trust in the seriousness and assured anonymity of the survey and thus have given less honest answers. Because of the lack of experience with the questionnaire or the questions and since the interviewer could not help and motivate as much as when being there in person, respondents might have given less reliable or valid answers. On the other hand, because of the greater ‘distance’, the social desirability bias, where respondents give answers that might please or impress the interviewer, could have been less pronounced. Besides the described possible changes of data collection modes and the possible impact on the data quality, some countries might not have had the opportunity to change their face-to-face mode – at least at the beginning of the crisis. Therefore, there might have been a (short) period, were no data collection was possible due to government restrictions and the time needed to prepare to switch to another survey mode. Moreover, people might not have wanted to participate in the survey (if voluntary) because of the risk of infection. This could have increased nonresponse rates. Countries using CATI might not have needed to change their survey mode but could nevertheless have been affected by restrictions caused by the pandemic. For example, call centers might have had to close at least for a certain period, which could have led to missing data. Besides all the mentioned possible negative impact that the pandemic might have (had) on the quality of the EU-LFS data, in conclusion, at least one more potential positive effect of the pandemic should be mentioned. Because of the travel restrictions and the increasing number of people working remotely from home in many participating countries of the EU-LFS, people selected for the survey were more likely to be at home. This could have led to less proxy interviews and thus less inadequate or unreliable answers from the proxies.

Context

The COVID-19 health crisis hit Europe in January and February 2020, with the first cases confirmed in Spain, France and Italy. COVID-19 infections have now been diagnosed in all European Union (EU) Member States. To fight the pandemic, EU Member States have taken a wide variety of measures. From the second week of March, most countries closed retail shops apart from supermarkets, pharmacies and banks. Bars, restaurants and hotels have also been closed. In Italy and Spain, non-essential production was stopped and several countries imposed regional or even national lock-down measures which further stifled the economic activities in many areas. In addition, schools were closed, public events were cancelled and private gatherings (with numbers of persons varying from 2 to 50) were banned in most Member States.

The large majority of the prevention measures were taken during mid-March 2020 and most of the prevention measures and restrictions were kept for the whole of April and May 2020. The first quarter of 2020 is consequently the first quarter in which the labour market across the EU has been affected by COVID-19 measures taken by the Member States.

Employment and unemployment as defined by the ILO concept are, in this particular situation, not sufficient to describe the developments taking place in the labour market. In this first phase of the crisis, active measures to contain employment losses led to absences from work rather than dismissals, and individuals could not search for work or were not available due to the containment measures, thus not counting as unemployed.

Direct access to