Archive:Being young in Europe today - living conditions for children

- Data extracted in December 2017. Most recent data: Further Eurostat information, Main tables and Database. Planned article update: June 2021

This is one of a set of statistical articles that forms Eurostat’s flagship publication Being young in Europe today. It presents a range of statistics covering children’s (aged 0-17) living conditions in the European Union (EU), the vast majority of the data is derived from EU statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC), a wide-ranging source of information for analysing poverty and social exclusion.

A paper edition of the publication was also published in 2015. In late 2017, a decision was taken to update the online version of the publication (subject to data availability).

This article provides, among others: information relating to the risk of monetary poverty among children; details concerning the ease with which families with/without children can afford a range of goods; information on the housing conditions in which children live; as well as evidence linking a child’s risk of poverty and deprivation to their parents’ labour market situation and educational attainment.

Policymakers agree that children should ideally grow up in families with sufficient resources to meet their essential needs, while their future well-being is enhanced through ensuring they have access to a range of services and opportunities including, among others, early childhood education and recreational, sporting and cultural activities. Most EU Member States have a range of policies that aim to tackle child poverty: these tend to be based around promoting children’s rights, although there are differences in the balance struck between promoting universal measures and targeting support at specific (vulnerable) groups [1].

(% share)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_peps01)

(% share)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_pees01)

(% share)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_pees01)

(% share)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_peps01)

(% share)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_iw02)

(% share)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_lvhl60)

(% share)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_peps60)

(% share)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_mdes05)

(% share)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_mddu03)

(% share)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_mddd60)

(% share)

Source: Eurostat (ilc_hcmp04)

Main statistical findings

Poverty and social exclusion

Almost 3 out of every 10 children in the EU was at risk of poverty or social exclusion

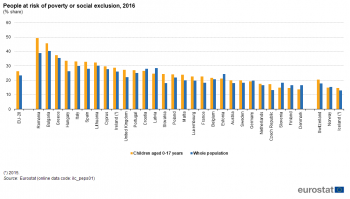

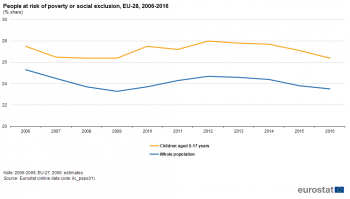

Figure 1 shows the proportion of people at risk of poverty or social exclusion in the EU since 2006, with information presented for children aged 0-17 years and for the whole population. There was some decrease in the risk of poverty or social exclusion up until the global financial and economic crisis (which began in 2008); however, thereafter there was an increase in the share of the population that was at risk of poverty or social exclusion. This was particularly true for children, as the gap between the risk of poverty or social exclusion for children and that for the whole population was wider following the crisis, peaking at 3.8 percentage points in 2010. By 2012, almost 3 out of every 10 children living in the EU-28 — some 28.0 % — were living at risk of poverty or social exclusion. From this recent high point, the share of children at risk of poverty or social exclusion fell for two consecutive years at a relatively modest pace, before decreasing at a faster pace in both 2015 and 2016, such that in 2016 a share of 26.4 % was recorded. For comparison, some 23.5 % of the total EU-28 population was at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2016.

Children accounted for more than one in five of those at risk of poverty or social exclusion

In absolute numbers, a total of 118 million persons in the EU-28 were at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2016; this figure included 25 million children. As such, children accounted for more than one fifth (21.2 %) of the total number of persons in the EU-28 at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2016.

Households with children are usually financially worse off when compared with households without children, as the former face more expenditure linked to the cost of bringing up children. Indeed, the number of children in a family directly influences the risk of monetary poverty shown through statistics, as each child in a family increases the family size and so reduces average income per family member. Governments may choose to target specific types of family units through social transfers and allowances (for example, child allowance or tax credits), often with the goal of encouraging people to have children. These transfers may balance, to some degree, the income situations of families with and without children, with social benefits and taxation likely to mitigate some of the differences.

The three conditions which concern the risk of poverty and social exclusion

The headline indicator covering the population at risk of poverty or social exclusion is defined as the share of the population in at least one of the following three conditions: i) at risk of poverty, which means living below the poverty threshold, ii) in a situation of severe material deprivation, iii) living in a household with low work intensity.

DEFINING POVERTY AND SOCIAL EXCLUSION

Persons at risk of poverty are those living in households with an equivalised disposable income below a certain threshold. The risk of poverty is a relative measure, which is conventionally set against a threshold of 60 % of the national median equivalised disposable income (after social transfers) — this means the poverty threshold varies between countries, as well as over time.

Severe material deprivation concerns persons whose living conditions are constrained by a lack of resources and experience of at least four out of nine deprivation items. The deprivation items concern the inability to be able to afford: i) to pay rent/mortgage or utility bills on time, ii) to keep their home adequately warm, iii) to face unexpected expenses, iv) to eat meat, fish or a protein equivalent every second day, v) a one week holiday away from home, vi) a car, vii) a washing machine, viii) a colour television, or ix) a telephone (including mobile telephones).

People living in households with low work intensity are those aged 0-59 years who live in households where the adults aged 18-59 years worked, on average, less than 20 % of their total work potential during the previous year; students are excluded.

Household income is equivalised (or adjusted) so that the incomes of different types of households can be compared, based on the premise that household income is shared and that there are some economies of scale which result from living together. To do so, total household disposable income is divided by the household’s size. To calculate the size, Eurostat uses the ‘modified OECD equivalence scale’ which first gives a weight of 1.0 to the first adult, 0.5 to any other household member aged 14 years and over, and 0.3 to each child aged 0-13 years and then the sums the weights within each household. The resulting average income figure is allocated to each member of the household, regardless of whether they are an adult or a child.

It is sometimes said that it is impossible to abolish poverty as the poverty line is always moving, and as income increases so too does the poverty line. However, it is possible for incomes to increase without affecting the median level of income: for example, a tax break for high wage earners would increase their disposable income without changing the median, while the introduction of a new social transfer targeted specifically at poorer people could result in some households being pulled above the poverty threshold without a change in the median level of income.

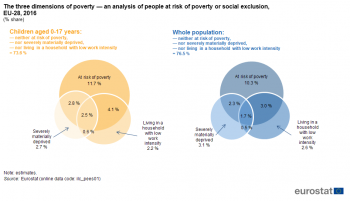

Figure 2 presents how these three conditions that make up poverty and social exclusion can overlap — note that a person can experience none, one, two or all three of these poverty and/or social exclusion conditions. Outside of the three circles shown in Figure 2, almost three quarters (73.6 %) of the children in the EU-28 did not experience any form of poverty or social exclusion in 2016, while the corresponding share for the whole population was higher, at 76.5 %.

Among the 25.0 million children in the EU-28 who were at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2016, some 9.3 million were simultaneously affected by more than one of these three conditions. Of these, 2.6 million children were at risk of poverty and severe material deprivation, 3.8 million were at risk of poverty and living in a household with low work intensity, 0.5 million were both materially deprived and living in a household with low work intensity, while 2.6 million were touched by all three conditions (in other words, those simultaneously at risk of poverty, in a situation of severe material deprivation and living in a household with low work intensity). As such, the proportion of children in the EU-28 that were experiencing all three poverty and social exclusion conditions was 2.5 % in 2016 — again this was higher than the corresponding average for the whole population (1.7 %).

Monetary poverty was the risk that most affected children

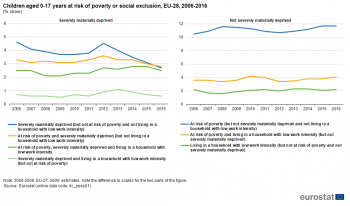

Figure 3 shows developments over time for the proportion of children at risk of poverty or social exclusion; it provides an analysis for the three conditions described above. From an analysis of the headline indicator, it is clear that monetary poverty — the proportion of children at risk of poverty (but not severely materially deprived and not living in a household with low work intensity) — was the most widespread form of poverty or social exclusion among children, affecting between 10.5 % and 11.7 % of all children in the EU during the period 2006-2016. The proportion of EU-28 children affected by any form of monetary poverty (in other words, on its own or in combination with one or both of the other conditions) stood at just over one in five (21.1 %) in 2016; this was higher than the proportion of the whole EU-28 population (children and adults) that was affected by any form of monetary poverty (17.3 %).

Between 2009 and 2014, about 650 thousand additional children in the EU experienced all three poverty and social exclusion conditions simultaneously — this was probably due, at least in part, to the effects of the global financial and economic crisis. Thereafter, the number of children in the EU-28 who were at risk of all three conditions fell by a modest amount in 2015 and this was followed by a larger decrease, of almost 270 thousand, in 2016.

The proportion of children suffering from severe material deprivation rose rapidly in 2012 then decreased slightly …

Prior to the global financial and economic crisis, the proportion of children in the EU-28 that were exclusively facing severe material deprivation or living in households with low work intensity fell, as the EU economy grew, disposable incomes and employment levels tended to rise, and with more people in work, on average households had more money to purchase goods and services. With the onset of the crisis, there was a subsequent increase in the proportion of children in the EU that were living in households with low work intensity (exclusively or in combination with other conditions) in 2009 and 2010; this was probably linked to increasing unemployment levels and precarious labour markets. The share of children suffering from material deprivation (exclusively or in combination with other conditions) rose at a modest pace in 2010 and 2011 and more rapidly in 2012, possibly reflecting a contraction in real wages and living standards. During the period 2012-2016, the proportion of children in the EU-28 who were materially deprived decreased and in 2016 returned to a level that was below that recorded at the onset of the crisis (see Figure 3).

… while the share of children at risk of monetary poverty rose at the onset of the financial and economic crisis and despite abating during the period 2009-2012, thereafter continued to rise

During a period of economic expansion in the EU (2005-2008), the share of children that were exclusively at risk of poverty (but not facing severe material deprivation or living in a household with low work intensity) rose. While this may seem a perverse result, it may be explained through an increasing degree of inequality in relation to the distribution of incomes. Although those at the lower end of the income scale saw their living standards rise during the period 2005-2008, the rate at which their incomes rose was slower than the average for the whole population, and as such a higher proportion of households and children fell into relative poverty. Following the onset of the global financial and economic crisis, the proportion of children that were at risk of monetary poverty started to fall (from 2009) — a pattern that continued through to 2012. With a gradual upturn in economic fortunes across the EU-28, the share of children exclusively at risk of monetary poverty once again started to increase, rising from a relative low of 10.7 % in 2012 to 11.7 % in both 2015 and 2016.

Among EU Member States where the overall risk of poverty was high the risk of poverty among children also tended to be high

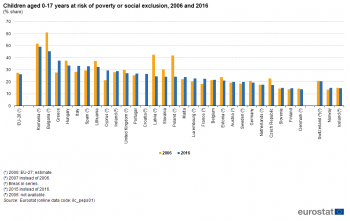

As already shown, children in the EU-28 were at a greater risk of poverty or social exclusion (26.4 %) than the average rate for the whole of the population (23.5 %) in 2016. Figure 4 shows that a similar pattern existed across the majority of the EU Member States, with the gap between the two rates particularly high in Romania, Hungary, Bulgaria, Spain and the United Kingdom, where the risk of poverty or social exclusion for children was at least 5 points above the national average. By contrast, there were seven Member States where a lower proportion of children were at risk of poverty or social exclusion: Latvia, Slovenia, Estonia, Denmark, Finland, Croatia and Germany.

In Romania and Bulgaria close to half of all children were at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2016, while relatively high rates — more than 30 % of all children — were recorded in Greece, Hungary, Italy, Spain and Lithuania. By contrast, the proportion of children at risk of poverty or social exclusion was much lower — less than 15.0 % — in Slovenia, Finland and Denmark.

Figure 5 shows a comparison between 2006 and 2016 for the proportion of children in the EU-28 at risk of poverty or social exclusion; note that this comparison over the last decade conceals considerable variations among the EU Member States, especially in relation to the impact of the global financial and economic crisis. During the period under consideration, the share of children at risk of poverty or social exclusion fell by 1.1 points across the whole of the EU-28. The Member States that displayed the greatest decrease in their share of vulnerable children in society between 2006 and 2016 were Latvia, Poland and Bulgaria (note that there is a break in series for all three Member States). The next largest decreases in at risk of poverty or social exclusion rates for children were recorded in Slovakia (-6.0 points), the Czech Republic (-5.3 points) and Lithuania (-4.8 points). Hungary, Estonia (break in series), the United Kingdom (break in series), Romania (2007-2016), Germany and Denmark (break in series) were the only other Member States to report a lower share of children at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2016 than in 2006.

The proportion of children at risk of poverty or social exclusion was particularly high among some of the EU Member States that were most deeply affected economically by the global financial and economic crisis

By contrast, some of the EU Member States where the proportion of children at risk of poverty or social exclusion rose at its most rapid pace between 2006 and 2016 were characterised as having been deeply affected by the global financial and economic crisis, for example, Greece, Cyprus (break in series), Italy or Spain (break in series). Alongside a contraction in economic activity, these Member States were also characterised by austerity measures, which may have impacted upon some measures and services designed to support children.

What impact does a parent’s education and job have on a child’s risk of poverty?

It can be argued that the opportunities afforded to children as they grow up should not be determined by the characteristics of the family into which they were born. That said, each child is born with a unique set of genes that may, at least in part, predispose them to certain abilities or levels of health. Furthermore, parents can influence the life outcomes for their children, through nurturing, encouraging aspirations and investing time and money in their education and health, while external social, cultural and economic environments may also play a role in shaping a child’s development. These determinants define a child’s life chances as they mature into adults, look for work, leave the parental home and start to establish their own family unit.

More than 1 in 10 households with dependent children were affected by in-work poverty

There is an old saying that work is the surest way to get out of poverty. However, in recent years there has been a sharp rise in precarious forms of employment in the EU, such as short-term contracts, low-pay or part-time work. Low wage growth, households where only one adult is in employment and households where those in work only have limited contracts are some of the reasons why an increasing share of working families remain at risk of poverty. Furthermore, it is likely that some parents work a limited number of hours each week in order to balance their professional and private lives; while for some this may be a lifestyle choice, the proportion of people that do so may, at least in part, be linked to the availability of adequate childcare arrangements for working parents [2].

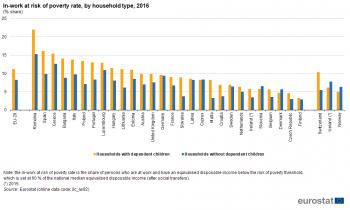

In-work poverty is defined as the proportion of persons who are at work and have an equivalised disposable income below the risk of poverty threshold, which is set at 60 % of the national median equivalised disposable income (after social transfers). Some 11.2 % of households in the EU-28 with dependent children faced the risk of in-work poverty in 2016, a share that was 3.0 points higher than that recorded among households without dependent children (See Figure 6). Romania (22.0 %) recorded the highest rate of in-work poverty for households with dependent children, followed by Spain (16.2 %) and Greece (15.4 %).

The in-work at risk of poverty rate was higher among households with dependent children (compared with those without children) in the majority of EU Member States. In 2016, the biggest differences were recorded in Romania (where the in-work at risk of poverty rate was 6.7 points higher among households with dependent children). There were also relatively large differences in Poland, Spain, Bulgaria, Lithuania and Slovakia (more than 5 points). By contrast, the in-work at risk of poverty rate was lower among households with dependent children (than for households without dependent children) in three Member States in 2016; Denmark, Slovenia and Cyprus.

PARENTAL EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT

Intergenerational poverty may be analysed in relation to the educational attainment of a child’s parents. The international standard classification of education (ISCED 2011) covers nine levels of education:

- ISCED level 0 — early childhood education;

- ISCED level 1 — primary education;

- ISCED level 2 — lower secondary education;

- ISCED level 3 — upper secondary education;

- ISCED level 4 — post-secondary non-tertiary education;

- ISCED level 5 — short cycle tertiary education;

- ISCED level 6 — Bachelor’s or equivalent level;

- ISCED level 7 — Master’s or equivalent level;

- ISCED level 8 — Doctoral or equivalent level.

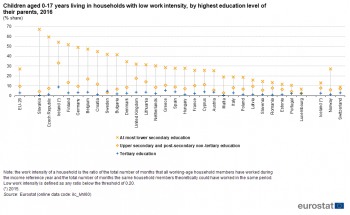

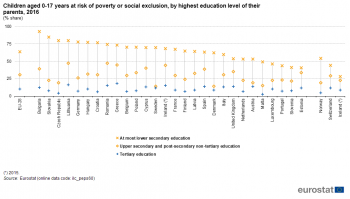

One out of four children whose parents had no more than a lower secondary level of education lived in households characterised by low work intensity

Figure 7 extends the analysis by looking at the share of children who live in households with low work intensity presented for each EU Member State by the highest level of education attained by either parent. Over one quarter (27.1 %) of all children in the EU-28 whose parents had at most a lower secondary level of education (ISCED levels 0-2) lived in a household with low work intensity in 2016. The share living in households with low work intensity was considerably lower among those children whose parents remained longer in the education system, falling to 9.7 % for children whose parents had an upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary level of education (ISCED levels 3 and 4), and to 3.0 % for children whose parents had a tertiary level of education (ISCED levels 5-8).

This pattern was repeated in all but one of the EU Member States in 2016; the exception was Sweden, where a higher proportion of children whose parents had a tertiary level of education were living in households with low work intensity when compared with children whose parents had no more than an upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education (4.6 % compared with 3.1 %).

Among children whose parents had no more than a lower secondary level of education, more than two thirds (67.2 %) of the children in Slovakia found themselves living in a household with low work intensity in 2016, a share that fell to less than 15.0 % in Slovenia, Romania, Estonia and Portugal, and to a low of 6.7 % in Luxembourg. By contrast, the proportion of children whose parents had completed a tertiary level of education and who found themselves living in households with low work intensity was considerably lower, ranging between a high of 8.7 % in Ireland (2015 data) and a low of just 0.2 % in Slovakia (while Malta, Romania and Slovenia also reported shares below 1.0 %).

Children whose parents had a higher level of education were, on average, exposed to a lower risk of poverty or social exclusion

Almost two thirds (63.7 %) of all children in the EU-28 whose parents had attained no more than a lower secondary level of education were at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2016 (See Figure 8). This group of children were more than twice as likely to face the risk of poverty or social exclusion as children whose parents had an upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education (30.6 %). The risk of poverty or social exclusion was considerably lower among those children whose parents had a tertiary level of education (10.3 %).

This pattern was repeated in each of the EU Member States with the risk of poverty or social exclusion for children consistently highest among children born to parents with low levels of educational attainment. Even in the Member States where the differences were at their smallest —Estonia, Slovenia, Luxembourg and Portugal — children whose parents had a low level of educational attainment were 30-37 points more likely to be at risk of poverty or social exclusion than children whose parents had a tertiary level of educational attainment. The level of parental educational attainment had a far greater impact on a child’s risk of poverty or exclusion in Croatia, Germany, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Bulgaria, as children whose parents had a low level of educational attainment had a risk of poverty or social exclusion that was 70-81 points higher.

Children of wealthier and more educated parents appear to have a higher chance of succeeding at school, better health [3], and (upon starting work) earn higher incomes, while the converse is true among those born into poorer families [4]. This section has shown that both in-work poverty and parental educational attainment may be closely linked to the risk of poverty or social exclusion, supporting the notion of intergenerational transmission of poverty (in other words, a cycle of poverty being passed from one generation to the next).

Material deprivation of children: the inability to afford a range of goods and services

The majority of the information presented in this article so far has been focused on relative measures of poverty, referring to national poverty thresholds. Material deprivation is an absolute measure of poverty and provides a useful complement to analyse poverty and social exclusion; for a definition of material deprivation and severe material deprivation, see the box titled ‘Defining poverty and social exclusion’. The indicators included in this section are defined in relation to the enforced inability to afford a range of goods and services, considered to be desirable or even necessary to lead an adequate life. A number of examples are presented, starting with the proportion of households that are in arrears on regular payments, before moving on to the (in)ability of households to afford a computer or a range of goods and services that cater for the specific needs of children.

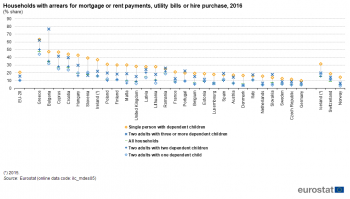

A higher proportion of households with children were in arrears for regular payments

Figure 9 provides an analysis by EU Member State in relation to the proportion of households that faced arrears in paying their mortgage or rent, utility bills or hire purchase items; in other words, people who could not keep up with the regular payments that most households face as part of their monthly budget. The information presented shows that, on average, single adult households with dependent children and households with two adults and three or more dependent children were more likely to face difficulties in making these regular payments than was typical for all households.

Some 10.4 % of all households in the EU-28 had arrears (for mortgage or rental payments, utility bills or hire purchase payments) in 2016. This figure rose to just over one in five (20.8 %) among households composed of a single adult with dependent children, while households composed of two adults and dependent children generally faced less difficulty in making regular monthly payments. This was particularly the case for two adult households with a single child or with two dependent children, as rates of 10.1 % and 10.3 % were slightly lower than the EU-28 average for all households. Households with a higher number of dependent children — three or more — faced more difficulties to make regular payments (15.9 %).

Among the EU Member States, more than half of all households composed of a single adult with dependent children in Greece (63.4 %) and around 45 % of households composed of a single adult with dependent children in Bulgaria, Cyprus and Croatia had arrears in 2016. The proportion of households composed of a single adult with dependent children in arrears was consistently higher than the average for all households in each of the EU Member States. In six Member States, namely Hungary, Slovenia, Ireland (2015 data), Cyprus, Malta and Poland, the proportion of single person households with dependent children that faced arrears was more than 20 points higher than the average for all households.

Some 15.9 % of households composed of two adults with three or more dependent children in the EU-28 faced arrears in 2016. This share rose to more than three quarters (76.7 %) of such households in Bulgaria, while it was also slightly less than two thirds (62.4 %) in Greece and close to two fifths in Cyprus (41.4 %) and Croatia (39.7 %). By contrast, less than 1 in 10 households composed of two adults and three or more dependent children in Denmark (4.1 %), Luxembourg (6.2 %), the Netherlands (6.9 %), Germany (7.3 %), the Czech Republic (8.3 %) and Sweden (8.6 %) faced arrears. In Denmark, Slovenia and Luxembourg the proportion of these households that faced arrears was slightly lower than the rate recorded for all households.

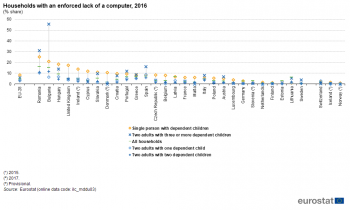

Single person households with dependent children faced greater difficulty in being able to afford a computer

Just less than 1 in 20 (4.6 %) households across the EU-28 faced difficulties in being able to afford a computer in 2016. Among those households where a single person was living with dependent children, this proportion rose to 8.3 %. By contrast, households composed of two adults with dependent children faced less difficulty in being able to afford a computer (see Figure 10).

Among the EU Member States, the households that were most likely to not be able to afford a computer were located in Bulgaria and Romania and composed of two adults with three or more dependent children. More than half (55.5 %) of these households in Bulgaria faced an enforced (for financial reasons) lack of a computer in 2016, while in Romania the equivalent share was 30.9 %; although considerably lower than the share in Bulgaria, the share in Romania was nevertheless almost twice as high as the next highest share, 16.1 % in Spain. In Bulgaria, the proportion of these households —composed of two adults with three or more dependent children — that were unable to afford a computer was 40.2 points higher than the average for all households in 2016, while in Romania the difference was 14.7 points. By contrast, in 16 of the EU Member States the proportion of households composed of two adults with three or more dependent children that faced difficulties in being able to afford a computer was lower than the national average for all households.

In Romania, slightly more than a quarter (25.2 %) of single person households with dependent children faced difficulties in being able to afford a computer in 2016. This share was higher than one fifth (21.0 %) among households with one adult and dependent children in Bulgaria, while the same difficulty was faced by more than one tenth of all households composed of a single adult with dependent children in Hungary, the United Kingdom, Ireland (2015 data), Cyprus, Slovakia and Denmark (2017 data). By contrast, single person households with dependent children sometimes faced less difficulty in being able to afford a computer than the average for all households. This gap was widest in Lithuania, where the proportion of households composed of a single adult with dependent children facing difficulties in being able to afford a computer was 5.6 points lower than the average for all households, followed by Estonia where this gap was 2.1 points; the share was also lower for households composed of a single adult with dependent children in Slovenia, Finland, Sweden and Latvia.

Households composed of two adults and no more than two dependent children often reported less difficulty in being able to afford a computer than the average for all households. The proportion of households with two adults and a single child or two dependent children that faced difficulties in being able to afford a computer was consistently lower than one tenth in 2016, other than for households with two adults and two dependent children in Bulgaria (11.6 %) and Romania (10.8 %) and households with two adults with one dependent child in Romania (10.1 %).

Severe material deprivation rates were slightly higher for children (than for the whole population)

The proportion of children in the EU-28 experiencing severe material deprivation was 1.0 points higher than the corresponding ratio for the whole population and stood at 8.5 % in 2016 (See Figure 11). While the share of children experiencing severe material deprivation was generally higher than that for the whole population, this pattern was not repeated across all of the EU Member States. Indeed, in Lithuania, Croatia, Latvia, Poland, Slovenia, Estonia, Luxembourg, Finland, Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden, a lower proportion of children faced severe material deprivation in 2016, albeit with rates that were generally less than a single point lower than for the whole population (the one exception was Lithuania where the difference was 2.0 points).

There were five EU Member States where the proportion of children experiencing severe material deprivation in 2016 was more than 4.0 points higher than the national average. This gap was largest in Romania (6.4 points higher), while the gap to the average for the whole population was within the range of 4.1-4.9 points in Cyprus, Bulgaria, Greece and Hungary.

Severe material deprivation among children inversely related to parental educational attainment

Across the EU-28, severe material deprivation in 2016 affected more than one quarter (27.2 %) of children whose parents had attained no more than a lower secondary level of educational attainment (See Figure 12). The proportion was considerably lower among children whose parents had attained an upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary level of education (9.0 %) or a tertiary level of education (1.9 %).

In 2016, the share of children experiencing severe material deprivation whose parents had a tertiary level of educational attainment was within the range of 0.5-1.0 % in Slovakia, Malta, Austria, Slovenia, Finland, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Poland and Germany, and was lower than 0.5 % in the Netherlands (0.3 %), Sweden (0.2 %) and Luxembourg (0.1 %). By contrast, at least three out of every five children whose parents had no more than a lower secondary level of educational attainment in Greece, Slovakia and Bulgaria faced severe material deprivation.

Housing quality and satisfaction

The cost and quality of housing are key elements that contribute to overall living standards and well-being. Indeed, the risk of poverty is strongly linked to the burden of sustaining a household and is therefore especially difficult for people with relatively low incomes.

As such, indicators that measure the quality, facilities and space available within dwellings may provide complementary information for assessing the material conditions of different groups within society. Housing quality can be assessed by looking at a range of housing deficiencies, such as a lack of sanitary facilities (a bath or shower, or indoor flushing toilet) and problems relating to the general condition of a dwelling (a leaking roof, or a dwelling that is considered to be too dark). Note that the statistics presented in this section refer to questions that were asked only once for all members of each household surveyed.

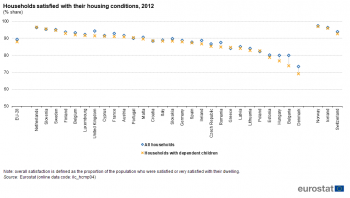

The vast majority of people in the EU-28 were satisfied with their overall housing conditions in 2012 (see Figure 13). Among the EU Member States, the highest degrees of satisfaction — for both the whole population and for households with dependent children aged 0-17 years — were recorded in the Netherlands and Slovenia, with both rates in excess of 95 %.

The lowest levels of satisfaction with housing conditions among households with dependent children were recorded in Bulgaria (73.9 %) and Denmark (69.0 %). These were the only EU Member States where less than three quarters of the households containing children were satisfied with their housing conditions in 2012. The same two Member States also recorded the largest differences in satisfaction rates between households with dependent children and the whole population, as the level of satisfaction among households with children was 6.1 points lower than for the whole population in Bulgaria and 4.3 points lower in Denmark. More generally, households with children were usually less inclined to be satisfied with their housing conditions, although this pattern was reversed in Greece, Portugal, Croatia, Poland, Slovenia and the Netherlands.

HOUSING

One dimension for assessing the quality of housing conditions is the availability of sufficient space in a dwelling. The overcrowding rate describes the proportion of people living in an overcrowded dwelling, as defined by the number of rooms available to the household, the household’s size, as well as its members’ ages and their family situation.

The severe housing deprivation rate is defined as the share of the population living in dwellings which are considered as being overcrowded, while at the same time having at least one of the following housing deprivation measures: no bath/shower and no indoor toilet; a leaking roof; or a dwelling considered too dark.

More than one in five households with children complained about a lack of space

A shortage of space is one among a range of reasons that may be cited in relation to dissatisfaction with a dwelling. The proportion of households with dependent children in the EU-28 reporting a shortage of space was 22.0 % in 2012 (some 7.2 points higher than the corresponding share for the whole population); this is perhaps not surprising given that many children have to share a bedroom with their siblings (See Figure 14).

Around one third of households with children in Bulgaria, Romania and Poland reported a shortage of space in their dwelling in 2012, with this share peaking in Latvia at 36.3 %. By contrast, less than one in five households with dependent children reported a lack of space in eight of the EU Member States, with the lowest shares being recorded in the Czech Republic (15.1 %) and the Netherlands (14.8 %).

The proportion of households reporting that they did not have enough space was consistently higher among those with dependent children when compared with the average for the whole population in 2012; the difference was generally within the range of 5-10 points, although it was higher in Latvia, Estonia, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria.

Almost one quarter of all households with dependent children suffered from overcrowding

To some degree the indicators presented above may be considered as subjective, insofar as they are based upon the perception of each respondent. An analysis of housing quality and satisfaction can be extended and balanced by referring to a range of objective indicators. Indeed, EU-SILC provides a measure of overcrowding that is based on the number of rooms and the number of people living in a household. In 2016, the EU-28 overcrowding rate [5] for households with dependent children was 23.8 %, which was 14.4 points higher than the corresponding share for households without dependent children.

The highest rates of overcrowding among households with dependent children were observed in Romania (67.5 %), Bulgaria (61.8 %), Hungary (59.7 %), Latvia (59.1 %), Croatia (52.7 %), Slovakia (52.6 %) and Poland (51.3 %); these were the only EU Member States to report that more than half of their households with dependent children were overcrowded.

There were nine EU Member States in 2016 with overcrowding rates for households with dependent children that were less than 10.0 %; the lowest shares (less than 5.0 %) were recorded in Malta, the Netherlands and Cyprus. The Netherlands and Finland were the only EU Member States to report that their overcrowding rate for households with dependent children was lower than their rate for households without dependent children (see Figure 15).

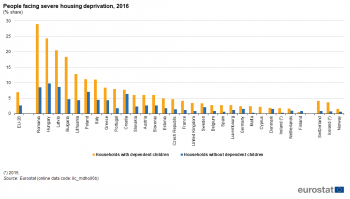

Severe housing deprivation is defined in relation to insufficient space and poor amenities [6]. In 2016, the severe housing deprivation rate for households with dependent children in the EU-28 was 6.9 %, which was 2.7 times as high as the corresponding rate for households without dependent children (2.6 %).

In 2016, the highest severe housing deprivation rates among households with dependent children were exhibited by Romania (29.0 %), Hungary (24.3 %) and Latvia (20.5 %); all of the remaining EU Member States recorded severe housing deprivation rates for households with dependent children that were below one fifth. By contrast, rates were within the range of 1.0-2.0 % for households with dependent children in the Netherlands, Ireland (2015 data) and Denmark, falling to less than 1.0 % in Finland.

A comparison between severe housing deprivation rates for people living in households with and without dependent children in 2016 reveals that the former were, with the exception of Finland, more affected by severe housing deprivation. This was particularly the case in Romania, Hungary, Bulgaria and Latvia, where people living in households with dependent children recorded rates that were more than 10 points higher than those for people living in households without dependent children. In Cyprus, Malta, Ireland (2015 data), Spain and Portugal, people living in households with dependent children were more than four times as likely (as people living in households without dependent children) to face severe housing deprivation (see Figure 16).

Conclusions: what does the future hold for child poverty and social exclusion in the EU?

Children that grow up in poverty are more likely to suffer from social exclusion and other negative outcomes in life, while they are also less likely to develop to their full potential. Breaking this cycle of disadvantage in a child’s early years can potentially reduce the risk of poverty or social exclusion.

Although tackling poverty and social exclusion can lead to benefits not only for the individuals concerned but also for society at large, the economic climate of austerity measures did little to help policymakers face these widespread challenges. Furthermore, in recent years there have been signs that the (re-)distribution of income is becoming increasingly unequal in the EU while real incomes have stagnated or even fallen in a number of EU Member States that were particularly affected by the crisis. This has resulted in an increasing share of the EU’s population suffering from a lack of work, monetary poverty and/or social exclusion and material deprivation. The impact of the crisis was proportionally greater for households with children than for those without.

This article has shown that the risk of poverty is more common among children than it is for the population as a whole. This is particularly the case when children live in households that are characterised by the presence of a single adult or a low degree of work, while parental educational attainment also appears to have a marked impact upon the risk of poverty or social exclusion experienced by children.

Data sources and availability

The data used in this article are primarily derived from EU statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC), established under Regulation 1177/2003. EU-SILC is a multi-purpose instrument that focuses mainly on income, but also gathers information on social inclusion/exclusion, material deprivation, housing conditions, labour market participation, education and health. It is carried out annually and has a reference population of all private households and their current members residing in the territory of EU Member States; persons living in collective households and in institutions are generally excluded from the target population. The EU-28 aggregate is a population-weighted average of individual national figures. Children are defined as persons aged 0-17 years.

Context

GIVING CHILDREN A LIFE CHANCE

The risk of poverty among children appears to be closely linked to the composition of the household into which they are born, in particular, the labour market situation, marital status and educational attainment of their parents. Some commentators believe that such a cycle of poverty and social exclusion may be broken by targeting children in their early years. However, in light of the global financial and economic crisis, there has been an increase in the risk of poverty among children, which may at least in part be attributed to austerity measures and decreasing investment.

EU POLICY MEASURES IN RELATION TO POVERTY AND SOCIAL EXCLUSION AMONG CHILDREN

The European platform against poverty and social exclusion is one of seven flagship initiatives of the Europe 2020 strategy which advocates not only smart and sustainable — but also inclusive — growth. The European Council adopted in June 2010 a headline target for social inclusion, namely, that by 2020 there should be at least 20 million fewer people in the EU who are at risk of poverty or social exclusion. This headline indicator measures the number of people affected by at least one of three forms of poverty or social exclusion: monetary poverty, material deprivation or low work intensity. To meet the overall target, individual EU Member States set their own national targets, which were generally expressed as absolute numbers of people to be lifted out of the risk of poverty or social exclusion (compared with national levels for 2008). The EU financially supports such actions through its social investment package and through the EU’s funds, in particular the European Social Fund.

A European Commission Recommendation, Investing in children: breaking the cycle of disadvantage (2013/112/EU) addressed poverty and social exclusion among children, promoting children’s well-being. It encouraged the EU Member States to go beyond ensuring children’s material security, by promoting equal opportunities so that all children might achieve their full potential, providing a focus on children who faced an increased risk due to multiple disadvantages. It stressed the need to develop integrated strategies based on three pillars:

- access to adequate resources (for example, providing children with adequate living standards through a combination of benefits);

- access to affordable quality services (for example, reducing inequality by investing in early childhood education and care, or improving the responsiveness of health systems to address the needs of disadvantaged children); and

- promoting children’s right to participate (for example, supporting the participation of children in play, recreation, sport and cultural activities).

See also

- All articles from the publication Being young in Europe today

- Children at risk of poverty or social exclusion

Further Eurostat information

Publications

Statistical books and pocketbooks

- Living conditions in Europe — 2014 edition

- Monitoring social inclusion in Europe — 2017 edition

- Quality of life — facts and views — 2015 edition

Statistical working papers

Main tables

Database

- People at risk of poverty or social exclusion (Europe 2020 strategy) (ilc_pe)

- Income distribution and monetary poverty (ilc_ip)

- Living conditions (ilc_lv)

- Material deprivation (ilc_md)

- EU-SILC ad-hoc modules (ilc_ahm)

- Youth (yth), see

- Youth social inclusion (yth_incl)

Dedicated section

Methodology / Metadata

- Income and living conditions (ilc) (ESMS metadata file — ilc_esms)

Source data for tables, figures and maps (MS Excel)

![]() Living conditions: tables and figures

Living conditions: tables and figures

Other information

- Commission Recommendation (2013/112/EU) of 20 February 2013 on Investing in children: breaking the cycle of disadvantage

- Communication (COM(2010) 758 final from the European Commission of 16 December 2010 concerning the European platform against poverty and social exclusion: a European Framework for social and territorial cohesion

- Regulation (EC) No 1177/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 June 2003 concerning Community statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC)

External links

Notes

- ↑ See ‘SPC advisory report to the European Commission on tackling and preventing child poverty, promoting child well-being’of 27 June 2012.

- ↑ See the publication ‘Gender equality in the workforce: reconciling work, private and family life in Europe’.

- ↑ J. W. Lynch and G. Kaplan, ‘Socioeconomic position’, in Social Epidemiology, L. F. Berkman and I. Kawachi, Eds., pp. 13-25, Oxford University Press, New York, NY, USA, 2000.

- ↑ See Raise household income to improve children's educational, health and social outcomes.

- ↑ The overcrowding rate is defined as the proportion of the population living in an overcrowded household. Overcrowded households do not have at their disposal a minimum number of rooms equal to: one room for the household; one room per couple in the household; one room for each single person aged 18 years and over; one room per pair of single people of the same gender aged 12-17 years; one room for each single person aged 12-17 years and not included in the previous category; one room per pair of children aged 0-11 years.

- ↑ Housing deprivation is a measure of poor amenities and concerns households living in a dwelling with a leaking roof, no bath/shower and no indoor toilet, or a dwelling considered too dark. The severe housing deprivation rate is defined as the proportion of the population living in a dwelling which is considered as overcrowded, while also exhibiting at least one of the housing deprivation measures.