Archive:SDG 4 - Quality education (statistical annex)

Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all (statistical annex)

- Data extracted in October 2017. Most recent data: Further Eurostat information, Main tables and Database. Planned article update: September 2018

This article provides an overview of statistical data on SDG 4 ‘quality education’ in the European Union (EU). It is based on the set of EU SDG indicators for monitoring of progress towards the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in an EU context.

This article is part of a set of statistical articles, which are based on the Eurostat publication ’ Sustainable development in the European Union — Monitoring report on progress towards the SDGs in an EU context (2017 edition)’. This report is the first edition of Eurostat’s future series of monitoring reports on sustainable development, which provide a quantitative assessment of progress of the EU towards the SDGs in an EU context.

Early leavers from education and training

The share of early leavers from education and training in the EU has fallen continuously since 2002 and is well on track to reaching the 10 % target in 2020. The gender gap has also narrowed, with men slowly catching up to women

Source: Eurostat (sdg_04_10))

Source: Eurostat (sdg_04_10))

The EU has defined upper secondary education as the minimum desirable educational attainment level for EU citizens. The skills and competences gained in upper secondary education are considered essential for successful entry into the labour market and as the foundation for lifelong learning. The indicator ‘early leavers from education and training’ measures the share of the population aged 18 to 24 with at most lower secondary education who were not involved in any education or training during the four weeks preceding the survey. Data presented in this section stem from the EU Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS).

Figure 1 shows that the share of early leavers has been falling continuously in the EU since 2002, albeit more slowly in recent years.

Despite marked overall progress towards reaching the Europe 2020 target, significant disparities exist between women and men and between native inhabitants and those born elsewhere. Men tend to leave education and training earlier than women in the EU. Although this gap has been narrowing since 2004, it remained substantial with 12.2 % of men on average and 9.2 % of women leaving early in 2016.

A person’s country of birth is another factor that strongly influences the rate of early leaving. There is clear evidence that foreign-born people tend to find it more difficult to complete their education than the native population. In 2016, the share was twice as high for people born outside the EU than for people studying in their country of birth. Most at risk are foreign-born men, with an early leaving rate of 21.1 % in 2016 [1].

People with disabilities — people who are limited in work activity because of a long-standing health problem or a basic activity difficulty (such as sight, hearing, walking or communicating difficulties) (LHPAD) — appear extremely disadvantaged. In 2011, 31.5 % of disabled people left education and training early compared to 12.3 % of non-disabled young people [2]. Low educational attainment, referring to at most lower secondary education, influences other socioeconomic variables. The most important of these are employment, unemployment and the risk of poverty or social exclusion. Early leavers and low-educated young people face particularly severe problems in the labour market, because about 58 % of 18 to 24 year olds with at most lower secondary education and who were not in any education or training were either unemployed or inactive in 2016. The situation for early leavers has worsened over time. Between 2008 and 2016, the share of 18 to 24 year old early leavers who were not employed but who wanted to work grew from 30.6 % to 37.4 % [3].

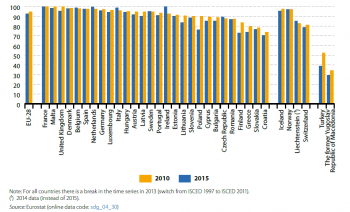

As 4.2 shows, rates of early leaving varied widely across Member States, ranging from about 3 % to almost 20 %. About two-thirds of Member States showed reductions in early leaving between 2011 and 2016, with the strongest decreases reported by southern European countries like Portugal, Spain and Greece.

Early childhood education and care

The share of children participating in early childhood education and care has grown continuously since 2001 and had almost met the target of 95 % in 2015.

Source: Eurostat (sdg_04_30))

Source: Eurostat (sdg_04_30))

Early childhood education and care (ECEC) is increasingly recognised as an integral part of the education and training system. The EU therefore aims for all children between four years old and the age of compulsory primary education to be able to access and benefit from high quality education and care and included the benchmark of a participation rate of at least 95 %in its ET 2020 framework [4]. Data presented in this section stem from the joint UIS (UNESCO Institute of Statistics)/OECD/Eurostat (UOE) questionnaires on education statistics, which constitute the core database on education. The UOE data collection is an administrative data collection administered jointly by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization — Institute for Statistics (UNESCO-UIS), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the Statistical Office of the European Union (EUROSTAT).

Participation in ECEC has grown more or less continuously in the EU since 2001. In 2015, 94.8 % of children between the age of four and the starting age of compulsory education participated in ECEC, this is 8.2 percentage points higher than in 2001. Therefore, the ET 2020 benchmark of 95 % has almost been reached in 2015.

In general, ECEC can also be applied to children from birth to the start of compulsory primary schooling. In most European countries, ECEC is therefore split into two phases: early childhood educational development programmes with educational content designed for younger children (in the age range of 0 to 2 years); and pre-primary education for children aged between three and the starting age for primary education [5]. Contrary to the older age group, ECEC and formal childcare participation among children under three is very low. The participation rate in formal childcare (between 1 and 29 hours) for children less than three years stood at 14.8 % in comparison to children from three years to the minimum compulsory school age with 34.0 % [6].

There is considerable variation in participation in ECEC across the EU, ranging from 100 % to 73.8 %in 2015. Half of the Member States had already exceeded the ET 2020 benchmark in 2015, implying almost universal enrolment in some form of education for children between the age of four years and the compulsory education age.

Underachievement in reading, maths and science

One-fifth of 15-year-olds showed insufficient abilities in reading, maths and science in 2015. This share is higher than in 2012, indicating the EU is not making sufficient progress towards reaching the target in 2020.

Source: Eurostat (sdg_04_40))

Source: Eurostat (sdg_04_40))

Achieving a certain level of proficiency in basic skills is a key objective of all educational systems. Basic skills, such as reading a simple text or performing simple calculations, provide the foundations for learning, gaining specialised skills and personal development. People need these skills to complete basic tasks and to participate fully in and contribute to society. The consequences of underachievement if it is not tackled successfully will be costly in the long run, for both individuals and for society as a whole[7] .

Various factors contribute to underachievement, for example an unfavourable school climate, violence, insufficient learning support or poor teacher-pupil relationships.

The data presented in this section stem from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), which is an internationally standardised assessment developed by the OECD and administered to 15-year-olds in schools. The ET 2020 framework aims to reduce the proportion of underachieving 15-year-olds in reading, maths and science to below 15 %by 2020. The benchmark refers to the OECD’s PISA study[8], in which underachievement is defined as failing to reach level 2 (‘basic skills level’) on the PISA scale for the three domains.

According to most recent PISA study results, every fifth 15-year-old EU pupil showed insufficient abilities in reading, maths and science in 2015. Test results were best for reading, with a 19.7 % share of low achievers, followed by science with 20.6 % and maths with 22.2 %.

These results show that the EU is seriously lagging behind in all three domains when it comes to progress towards the ET benchmark of less than 15 %. Compared to 2009 and 2012, the share of low achievers has increased for reading and science, while for maths it has remained stable at a high level.

Gender differences are most pronounced for reading skills, with girls clearly outperforming boys. While only 15.9 %of 15-year-old girls scored low in this domain in 2015, the share of low-achieving boys was 23.5 %. In contrast, gender gaps in maths and science remained negligible.

Large discrepancies in reading, maths and science skills also exist across the EU. However, achievement levels of the different skills appear to be closely related, with Member States that show certain levels of achievement in one area tending to show a similar value in the others. By 2015, only Estonia and Finland had reached the ET 2020 benchmark, with a share of low achievers in all three domains below 15 %.

Tertiary educational attainment

The tertiary educational attainment rate of 30 to 34 year olds has increased by 15.5 percentage points since 2002 and is on track to reach the target of 40 %. But the gender gap has widened considerably, with men falling further and further behind.

Source: Eurostat (sdg_04_20))

Source: Eurostat (sdg_04_20))

Raising the share of the population aged 30 to 34 that has successfully completed tertiary education to at least 40 % is another ET 2020 target. Educational attainment is defined according to the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED). Tertiary educational attainment refers to ISCED 2011 level 5–8 (for data as from 2014) and to ISCED 1997 level 5–6 (for data up to 2013). The data presented in this section stem from the European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS), a household survey based on European legislation.

The share of 30 to 34 year olds with tertiary educational attainment has grown steadily since 2002, mirroring increases across all Member States. This to some extent reflects Member States’ investment in higher education to meet demand for a more skilled labour force. Moreover, the increases can also be ascribed to the shift to shorter degree programmes following implementation of Bologna [9] process reforms in some countries.

Despite the overall positive trend, the gender gap among tertiary education graduates has significantly widened across the EU. While in 2002 the share was similar for women and men, the increase up to 2016 was almost doubled for women, who in 2016 were already clearly above the ET 2020 benchmark, at 43.9 %. In contrast, the share among 30 to 34-yearold men was nearly 10 percentage points lower, at 34.4 %.

There is also difference in terms of migrant status. In 2016, the tertiary educational attainment rate was more than 4 percentage points higher for native-born residents than for the foreign-born population. And within the foreign-born group, the rate was considerably lower for people from outside the EU than for those from another Member State. But no clear patterns can be observed at individual country level. While some Member States showed gaps of more than 30 percentage points between native-born residents and those who were foreign born, others such as Latvia and Denmark showed a reverse pattern, with the foreign-born population having higher attainment rates [10] . This may reflect differences in the migrant patterns across Europe (both out- and in-flows), with some Member States attracting and retaining people with high skill levels and others attracting a lower-skilled population [11].

Moreover, people with disabilities find it harder to complete tertiary education. About 36 % of people aged 30 to 34 without disabilities attained this educational level in 2011 compared with around 22 % for those with a limitation caused by a LHPAD [12].

In 2016 there was more than a twofold difference in tertiary attainment rates across Member States, ranging from 25.6 % to 58.7 %. Overall, in about two-thirds of the Member States the rate was above or equal to the overall EU figure. Although tertiary educational attainment rates have increased in almost all EU countries since 2011, the gap between the top and the bottom end of the scale has widened.

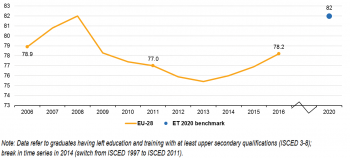

Employment rate of recent graduates

Despite recent increases, the employment rate of recent graduates aged 20 to 34 with at least upper secondary education remains far from the ET 2020 benchmark. Gender differences have increased again in recent years.

Source: Eurostat (sdg_04_50))

Source: Eurostat (sdg_04_50))

The employment rate of recent graduates is defined as the percentage of the population aged 20 to 34 with at least upper-secondary education (ISCED 2011 levels 3 to 8) who are in employment, not in any education or training during the four weeks preceding the survey, and who have successfully completed their highest educational attainment one to three years before the survey. It provides information on the transition from education to work and helps analyse access to the labour market among recent graduates. Data presented in this section stem from the EU Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS).

A look at trends for the past ten years shows that recent graduates have been particularly affected by the economic crisis. Between 2008 and 2013, employment rates among 20 to 34 year olds who had left education and training in the past one to three years fell by 6.6 percentage points. In comparison, the overall employment rate for 20 to 64-year-olds declined by ‘only’ 1.9 percentage points over the same period. However, 2013 seems to mark a turning point, with the share of recent graduates with a job increasing year on year, reaching 78.2 % in 2016.

Figure 9 shows graduates who left education and training with at least upper secondary qualifications (ISCED levels 3 to 8). Disaggregation by educational attainment reveals that the fall in the employment rate had been slightly stronger for the lower educated cohort (– 4.4 percentage points from 2008 to 2016) than for those with tertiary education (– 4.1 percentage points from 2008 to 2016) [13].

In general, recent male graduates were more likely to find employment than their female counterparts. In 2016, the rate for men (80.8 %) was clearly higher than the rate recorded among women (76.0 %). This pattern has been apparent since 2006 but its intensity has changed over time. The largest gender gaps were recorded in 2005 and 2007. The gap shrank again significantly with the onset of the economic crisis, but widened in 2010 and remained within the 3.3 to 4.5 percentage point range in favour of young male graduates between 2010 and 2016. Some of these gender differences may be explained by the nature of the different fields typically studied by women and men (for example, a higher proportion of science and technology students tend to be male) and by differences in labour market demand for graduates with different skills[14].

Overall, employment rates rise with educational level, indicating that a person with a higher educational attainment has a comparative advantage on the labour market. In 2016, the employment rate of recent graduates with tertiary education (ISCED 2011 levels 5–8) was 10.2 percentage points higher than people from the same age group with only middle educational attainment (ISCED 2011 levels 3 and 4). The gap has fallen slightly from 11.3 percentage points in 2011. Some of the difference between the lower educated cohort and the tertiary graduates may be linked to the latter deciding to take jobs for which they were over-qualified in order to get into the labour market. Thereby, they are boosting the employment rate for tertiary graduates while at the same time lowering the rate for other graduates. This may be especially important in those cases where labour market demand is subdued, for example, following the onset of the global financial and economic crisis [15].

As shown for other education indicators in this chapter, the foreign-born population is also disadvantaged as far as the employment status of recent graduates is concerned. In 2016, the proportion of employed recent graduates varied between the native-born population and the foreign-born one by 4.3 percentage points [16].

Employment rates of recent graduates vary widely across Member States, ranging from 96.6 % to 49.2 %. Overall, 11 Member States reported rates above the 82 % benchmark in 2016. Between countries, not only the employment rate of recent graduates varied, but also the differences between women and men. While in most EU countries more recent male graduates found a job within one to three years of leaving education, in Sweden, Latvia, Lithuania, Ireland, France, Belgium and Austria the gender gap favoured women.

Adult participation in learning

The share of 25 to 64 year olds participating in learning has stagnated over the past decade, remaining far from the 15 % target set for 2020.

Source: Eurostat (sdg_04_60))

Source: Eurostat (sdg_04_60))

Adult participation in learning (previously named ‘lifelong learning’) refers to people aged 25 to 64 who stated that they received formal or non-formal education and training in the four weeks preceding the survey (numerator). The denominator consists of the total population of the same age group, excluding those who did not answer to the question ‘participation in education and training’. Adult learning covers formal and non-formal learning activities — both general and vocational — undertaken by adults after leaving initial education and training [17]. The ET 2020 framework includes the target to increase the share of adults participating in learning to 15 %.

Data presented in this section stem from the EU Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS).

Adult participation in learning has stagnated at a rather low level in the EU over the past decade. Pronounced increases were only observable between 2002 and 2005 and from 2012 to 2013. However, this most recent growth can mainly be attributed to a methodological change in the French Labour Force Survey in 2013 [18]. Over the past four years, the share of 25 to 64 year olds participating in learning stagnated at slightly below 11 %, far from the 15 % target. Furthermore, the results of the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) show that significant numbers of EU adults struggle with literacy, numeracy and digital skills.

Women are more likely to participate in adult learning than men. In 2016, the share of women engaged in adult learning was nearly two percentage points higher than that of men (11.7 % compared with 9.8 %). The women’s rate was not only clearly above the men’s rate, but had also been improving faster with a plus of four percentage points since 2002 compared with 3.2 percentage points for men. Women recorded higher participation rates in all Member States except for Germany and Croatia, where a slightly higher share of men were engaged in adult learning. Greece and Romania showed no perceivable difference in gender participation rates.

Interestingly, the two countries with the highest adult learning shares in general showed the largest gender differences: Sweden with 14.0 percentage points and Denmark with 9.9 percentage points.

There is a clear gradient of adult participation in learning and a person’s educational attainment. In 2016 adults with at most lower secondary education were less engaged in learning (4.2 %) than those with upper secondary (8.8 %) or tertiary education (18.6 %).

Country-specific participation in adult learning varied considerably across the EU, with the lowest share being 25 times lower than the highest share in 2016. The Scandinavian countries stood out with by far the highest rates, followed by central European Member States. In general, adult participation in learning seems to be less common in eastern and southern European countries.

See also

Further Eurostat information

Database

- Socioeconomic Development

Dedicated section

Methodology

More detailed information on EU SDG indicators for monitoring of progress towards the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), such as indicator relevance, definitions, methodological notes, background and potential linkages, can be found in chapter 4 of the publication ’ Sustainable development in the European Union — Monitoring report on progress towards the SDGs in an EU context (2017 edition)’.

Notes

- ↑ Early leavers from education and training by sex and country of birth. Source: Eurostat (online data code: edat_lfse_02)

- ↑ Eurostat, Disability statistics — access to education and training (accessed 19 September 2017). It is foreseen to improve the availability of disability-related indicators in LFS for future monitoring.

- ↑ Early leavers from education and training by sex and labour status. Source: Eurostat (online data code: edat_lfse_14).

- ↑ See: European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice/Eurostat (2014), Key Data on Early Childhood Education and Care in Europe, p.11.

- ↑ See: European Commission (2015), Education and Training Monitor 2016, p. 50.

- ↑ Formal childcare by age group and duration — % over the population of each age group — EU SILC survey. Source: Eurostat (online data code: ilc_caindformal). Formal childcare refers to the four EU SILC survey variables: 1. Education at pre-school or equivalent; 2. Educationat compulsory education; 3. Child care at center-based services outside school hours and 4. Child care at day-care center organised/controlled by a public or private structure.

- ↑ European Commission (2016), PISA 2015: EU performance and initial conclusions regarding education policies in Europe, p.3.

- ↑ PISA is an international study that was launched by the OECD in 1997. It aims to evaluate education systems worldwide every three years by assessing 15-year-olds’ competencies in the key subjects: reading, mathematics and science. For further details see http://www.oecd. org/pisa/

- ↑ The Bologna process put in motion a series of reforms to make European higher education more compatible, comparable, competitive and attractive for students. Its main objectives were: the introduction of a three-cycle degree system (bachelor, master and doctorate); quality assurance; and recognition of qualifications and periods of study (source: Eurostat, Education and training statistics introduced (accessed 15 May 2017)).

- ↑ Population by educational attainment level, sex, age and country of birth. Source: Eurostat (online data code: edat_lfs_9912).

- ↑ European Commission (2015), Education and Training Monitor 2016, p. 50.

- ↑ Eurostat, Disability statistics — access to education and training (accessed 19 September 2017). It is foreseen to improve the availability of disability-related indicators in LFS for future monitoring.

- ↑ Employment rates of young people not in education and training by sex, educational attainment level and years since completion of highest level of education. Source: Eurostat (online data code: edat_lfse_24).

- ↑ Eurostat, Statistics Explained, Employment rates of recent graduates.

- ↑ Eurostat, Statistics Explained, Employment rates of recent graduates.

- ↑ Employment rates of young people not in education and training by sex, educational attainment level, years since completion of highest level of education and country of birth. Source: Eurostat (online data code: edat_lfse_32).

- ↑ The general definition of adult learning covers formal, non-formal and informal but the indicator adult participation in learning only covers formal and non-formal education and training. For more information, see: Eurostat, Participation in education and training.

- ↑ INSEE, the French Statistical Office, has carried out an extensive revision of the questionnaire of the Labour Force Survey. The new questionnaire was used from 1 January 2013 onwards. It has a significant effect on the level of various French LFS-indicators. Detailed information on these methodological changes and their impact is available in INSEE’s website, Box ‘Pour en savoir plus’.