Archive:Statistics comparing enterprises which trade internationally with those who do not

Economic globalisation and the participation of enterprises in international trade in goods are important drivers for growth, as a consequence an increasing number of enterprises is active internationally. In this article we utilise results from the latest European micro-data linking project, in which we managed for the first time ever to consistently divide the Structural Business Statistics enterprise population into those who trade internationally and those who are active in domestic markets only. This is important because these two groups of enterprises are known to behave differently. Accordingly we divide the enterprises along two dimensions: international trade and control. In the international trade-dimension we distinguish: 1) exporters, 2) importers, 3) two-way traders and 4) enterprises not involved in international trade. In the remainder of the article we will call this fourth category "domestic enterprises" (not to be confused with domestically controlled enterprises). To avoid having occasional traders in one of the first three groups we impose thresholds on imports and exports (see explanatory notes). In the control dimension we distinguish foreign-controlled and domestically controlled enterprises. In some parts we break down the domestically controlled enterprises into those with foreign affiliates and those without foreign affiliates. In the remainder of the article we will first present the main findings and give some background information on the project. Then we present characteristics first of the international traders, secondly of the exporters and thirdly of the importers. Finally there are some some notes and links to related information.

Main statistical findings

- More than one in five (23 per cent) of all manufacturing enterprises in the eight participating countries are international traders. Denmark and Austria have the highest shares (around 40 per cent); Germany is a little above average (25 per cent) while other countries were below the average.

- These international traders are very important for employment; they account for 76 per cent of total manufacturing employment, ranging from just under 90 per cent (Austria and Denmark) to 68 per cent (Portugal and Norway).

- Accordingly, the number of employees per enterprise is on average much larger in international traders than in domestic enterprises. On average, the largest international traders are in Finland while the largest domestic enterprises are in Germany.

- The share of foreign-controlled international traders ranges from 4.6 per cent in Portugal to 21.2 per cent in Latvia. Sweden (17.0) and Finland (11.9) are the only other countries with shares of more than 10 per cent.

- In most countries, exporters lost fewer jobs since the start of the crisis compared with non-exporters; the exceptions were the Nordic countries (Finland, Norway and Sweden).

- In all countries except Finland and Norway, growth of value added per enterprise is higher for exporters than for non-exporters. In all countries except Finland and Portugal, exporters have surpassed the pre-crisis level in growth of value added per enterprise. This is also the case for non-exporters in Austria, Norway and Sweden.

- Foreign-controlled exporters in manufacturing are very important for exports. In 2012, they accounted for more than half of total exports in Sweden and more than 40% in Latvia, Austria and Norway.

- In all participating countries, exports divided by full-time equivalent employment (FTE) were higher in foreign-controlled than in domestically controlled exporters.

- Foreign-controlled wholesale and retail importers account for the highest shares of imports in most countries. In 2012, in Sweden, they accounted for 62 per cent of total imports of goods.

- In all countries, import intensity is higher in foreign-controlled than in domestically controlled importers.

Background information

Economic globalisation and the participation of enterprises in international trade in goods are important drivers for economic growth. Evidence to demonstrate this is vital for designing policy. Research has shown that international traders differ substantially from domestic enterprises [1].

This article uses the results of eight European countries (Austria, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Norway, Portugal and Sweden) that participated in a micro-data linking (MDL) project. Each participating country constructed a national database with tailor-made, harmonised contents. This enables data analysis at enterprise level, comparing international traders and domestic enterprises. It also enables analysis of differences according to type of trading and/or control. The national databases cover reference years 2008 and 2012 enabling the analysis of developments since the economic crisis started.

The analysis splits the population into those taking part in international trade in goods — being an exporter, importer or two-way traders — and those that do not. We found that most enterprises are two-way traders, very few enterprises export without importing and vice versa. Exporters (including two-way traders) are of special interest for policy makers because of their potential job creation due to demand from markets abroad. Importers (again including two way traders) are also important since they facilitate access to the raw materials, intermediate goods and technologies that are otherwise not easily available. Therefore we analyse both exporters and importers.

The Economic globalisation indicators in manufacturing, wholesale and retail trade article , showed that manufacturing typically has greater shares of exports while wholesale and retail trade has greater shares of imports. Therefore this article analyses the manufacturing exporters and the wholesale and retail trade importers.

Characteristics of international traders

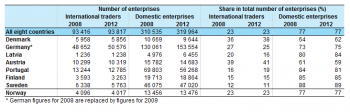

In 2012, in the eight European countries taking part in this project, 93.817 of 413.781 manufacturing enterprises — or 23 per cent — can be characterised as international traders (importers, exporters or two-way traders). The share of international traders in manufacturing differs from country to country (see table 1). The highest shares, around 40 per cent, are in Austria and Denmark. Between 2008 and 2012, the number of international traders dropped in five of the eight countries while the number of domestic enterprises fell in only four of the eight. For the eight countries as a whole the number of international traders grew with less than half a per cent while the number of domestic enterprises grew with three per cent.

In 2012, the international traders employed slightly more than 7.5 million employees (FTE) compared with less than 2.4 million in the domestic enterprises. These international traders are very important for employment: they account for 75 per cent of total employment, ranging from nearly 90 per cent in Austria and Denmark to 68 per cent in Portugal and Norway(see table 2).

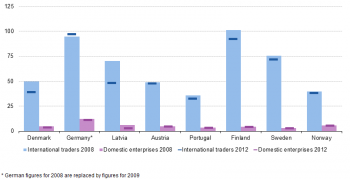

Comparing tables 1 and 2, we see that the number of international traders is much smaller than the number of domestic enterprises, but that the reverse is true for employment. Consequently, international traders are much larger than domestic enterprises (see figure 1). In 2012, in the eight countries considered, international traders had on average 76 employees (FTE) compared with 6.3 in the domestic enterprises. Accordingly, the number of employees per enterprise is, on average, much larger in international traders than in domestic enterprises. On average, the largest international traders are in Finland while the largest domestic enterprises are in Germany.

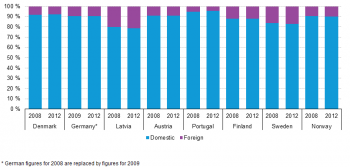

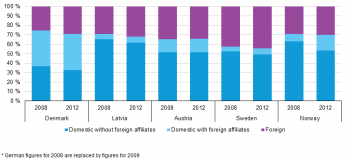

Not surprisingly, the majority of international traders in manufacturing are domestically controlled(see figure 2); in most countries, domestically controlled enterprises constitute at least 90 per cent of all international enterprises. The exceptions are Latvia (78 per cent), Sweden (83 per cent) and Finland (88 per cent). This pattern has not been influenced by the economic crisis as the shares remained stable from 2008 to 2012.

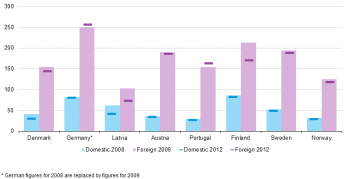

Although in manufacturing domestically controlled international traders — as a group — have more employees than foreign-controlled, they have fewer employees per enterprise (see figure 3). Moreover, from 2008 to 2012, there was a small drop in the number of employees (FTE) per enterprise in domestically controlled international traders in all countries. On average for all countries, foreign-controlled international traders in 2012 employed 168 full-time employees compared with only 50 for domestically controlled international traders.

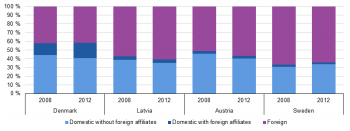

For some countries, it is possible to further divide domestically controlled international traders into those with and those without foreign affiliates (see figure 4). This shows that the highest shares of employment are in domestically controlled international traders without foreign affiliates. These results are consistent with the findings in published studies stating that the first and most common type of internationalisation is engagement in international trade — most employment is in domestically controlled enterprises without foreign affiliates, and a much higher share of domestically controlled international traders (not shown in the figure) do not have foreign affiliates. An exception to this is Denmark where employment shares of domestically controlled international traders — with and without foreign affiliates — are almost equal.

Characteristics of exporters

This section provides insights into the employment shares and economic performance of exporters compared with non-exporters by analysing their relative performance in terms of employment and value added creation. Furthermore, the section analyses exporters by type of control (foreign/domestically controlled) and type of trade (two-way traders/exporters only).

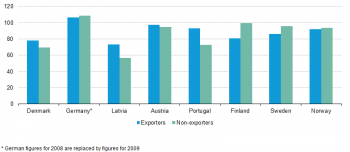

For all countries except Germany, employment in both exporting and non-exporting enterprises decreased from 2008 to 2012 (see figure 5). For the majority of countries, non-exporters lost more employment than exporters. However, the reverse is true in Finland, Sweden and Norway.

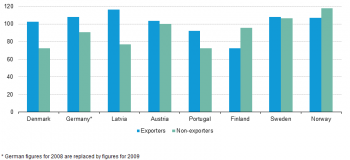

In all countries except Finland and Norway, growth of value added per enterprise is higher for exporters than for non-exporters (see figure 6). Furthermore although only German exporters have regained their pre-crisis employment shares, exporters in six of the eight countries have regained and even surpassed the pre-crisis level for value added per enterprise. This is also the case for non-exporters in Austria, Norway and Sweden. By combining the information in figures 5 and 6, we can conclude that in most countries exporters have increased their productivity more than non-exporters.

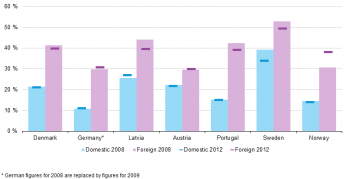

In most countries, a relatively large share of exports is generated by foreign-controlled traders but different development patterns can be identified (see figure 7). In Denmark, Germany (since 2009), Norway and Sweden, domestically controlled exporters lost export shares after the financial crisis, while in Finland they increased their share substantially. Latvia, Austria and Portugal also experienced small increases.

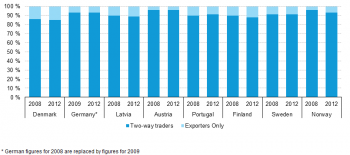

Interestingly, the great majority of exporters are also importers. These two-way traders account for at least 90 per cent of total exports in all countries except Denmark, Finland and Latvia (see figure 8). This share was stable at around 90 per cent between 2008 and 2012 indicating that exports and imports of goods is to a large extent carried out by a group of enterprises being internationally oriented and involved in global value chains both as importers and exporters.

For some participating countries, it was possible to deepen the analysis and compare foreign-controlled exporters with domestically controlled exporters with and without foreign affiliates. The results show that — except for Latvia — the greater share of exports in 2012 was generated by multinational exporters that are either foreign-controlled or have foreign affiliates, from 84 per cent in Denmark to 58 per cent in Sweden (see figure 9). When comparing this with employment (shown earlier in figure 5), it is clear that these multinational exporters have higher shares in exports than in employment. Apparently they benefit from the advantages of being part of an enterprise group and are able to generate more exports per employee than domestically controlled enterprises without foreign affiliates.

As revealed in the international enterprise analysis, when it comes to domestically controlled exporters, Denmark shows a quite different pattern from the other countries. Almost 50 per cent of total exports are generated by domestically controlled exporters with foreign affiliates, primarily due to some Danish strongholds in specific industries such as pharmaceuticals. Furthermore, from 2008 to 2012, the export share of Danish domestically controlled exporters without foreign affiliates dropped 23 by per cent. In the same period, the export share of domestically controlled exporters with foreign affiliates dropped by only 2 per cent.

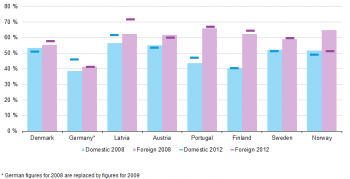

Export intensity is an important indicator of the degree of enterprise involvement in international trade. With export intensity close to 50 per cent or more for most countries, figure 10 clearly illustrates how vital exports are in the manufacturing sector across countries. Furthermore, the figure illustrates that export intensity in manufacturing, not surprisingly, is higher for foreign-controlled exporters than domestically controlled exporters. This is especially the case in Finland and Portugal which both show a significant difference between domestically and foreign-controlled exporters.

Finally, in most countries, both domestically and foreign-controlled exporters show a small increase or a stable progress in export intensity from 2008 to 2012. Only Latvia for foreign-controlled and Germany for domestically controlled exporters shows a slightly higher increase from 2008 to 2012.

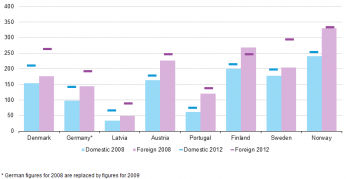

. Figure 11 illustrates that foreign-controlled exporters generate more exports per employee than domestically controlled traders. This indicator also shows an increase from 2008 to 2012 for all countries. However, while the comparative levels for domestically and foreign-controlled exporters for most countries has not changed much from 2008 to 2012, Denmark and Sweden saw a larger increase in exports per full-time equivalent employment in foreign-controlled than in domestically controlled exporters.

Characteristics of importers

Given the more direct importance of exports on domestic economic growth and employment, political interest has focused on exporting enterprises. But imports are also a major contributor to the competitiveness of the domestic economy. They provide access to the raw materials, intermediate goods and technologies that are not so easily available for domestic enterprises and consumers. So far, importing enterprises have attracted less attention than exporting ones, but enterprises that facilitate imports for possible inputs to domestic production — and their characteristics and performance —also have policy relevance.

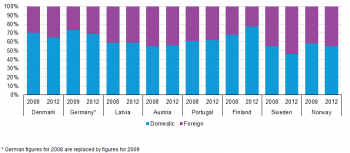

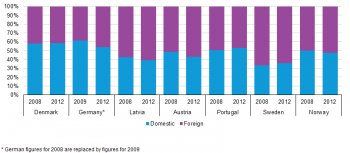

This article gives a first insight into the characteristics of enterprises importing goods in wholesale and retail trade (NACE Rev. 2 section G). Figure 12 provides an overview of how import shares are divided between domestic and foreign-controlled importers in wholesale and retail trade. In general, the shares are fairly equal for domestically and foreign-controlled importers. In the majority of participating countries, the shares were either stable or there was a small increase in import shares of foreign-controlled importers between 2008 and 2012. However, in both Denmark, Portugal and Sweden, foreign-controlled importers had a smaller share of imports in 2012.

As was the case for exports, the greater share of imports in 2012 came from multinational importers that are either foreign-controlled or have foreign affiliates, from close to 60 per cent in Denmark and Austria to 66 per cent for Sweden (see figure 13).

Just as we define export intensity as exports divided by turnover, we calculate import intensity as imports divided by purchases of goods and services. In both cases, they represent the share of a total that comes from abroad. In the case of import intensity, we divide by purchases of goods and services whereas the imports contain only goods. In the case of export intensity, we divide by turnover, which also includes services. However it is well-known that both imports and exports contain a service component and therefore it is justifiable to calculate the export and import intensities in this way.

In all countries, import intensity is higher in foreign-controlled enterprises than in domestically controlled enterprises (see figure 14). Generally, it was fairly stable between 2008 and 2012 except for foreign-controlled Norwegian enterprises where it increased by almost a quarter. The highest import intensity both in domestically and foreign-controlled enterprises is found in Sweden.

Data sources and availability

New statistics on enterprises have traditionally been produced by carrying out surveys. Micro data linking presents an innovative approach to obtaining new information on the economic performance of enterprises by linking different existing statistical sources at individual enterprise level (micro data level). This approach does not require new surveys to be carried out and thus does not increase the burden placed on enterprises. Due to statistical confidentiality issues it is not possible to publish micro data on the Eurostat website. However in the future Eurostat aims at publishing aggregated tables based on micro data analysis in its database.

See also

- Statistics_on_small_and_medium-sized_enterprises

- Business economy - size class analysis

- Microdata linking international sourcing

- Foreign affiliates employment by business function

- Entrepreneurship - statistical indicators

Further Eurostat information

Source data for tables, figures and maps (MS Excel)

Notes

This section briefly describes terms and definitions used in the paper.

- Export intensity

Export intensity is the share of exports in turnover.

- Import intensity

Import intensity is the share of imports in purchases of goods and services.

Trade typology

- International enterprise

International enterprises are enterprises that are engaged in exports or imports, or both, in accordance with the definition of exporters and importers mentioned below.

- Exporters

Exporters are enterprises that have exports greater than EUR 5 000 and export intensity of at least 5 per cent.

- Importers

Importers are enterprises that have imports greater than EUR 5 000 and import intensity of at least 5 per cent.

- Two-way traders

Two-way traders are enterprises that are engaged in both exports and imports.

- domestic enterprises

Domestic enterprises are enterprises that are not engaged in any trading activities above the thresholds mentioned above.

- ↑ M. Melitz, ‘The Impact of Trade on Intra-Industry Reallocations and Aggregate Industry Productivity’, Econometrica 71(6), 2003 and Helpman, E. et al., ‘Export versus FDI with Heterogeneous Firms’, The American Economic Review 94(1), 2004

[[Category:<Subtheme category name(s)>|Name of the statistical article]] [[Category:<Statistical article>|Name of the statistical article]]

Delete [[Category:Model|]] below (and this line as well) before saving!