Archive:Enlargement countries - finance statistics

- Data from September 2015. Most recent data: Further Eurostat information, Main tables and Database. Planned article update: October 2016.

This article is part of an online publication and provides information on a range of financial statistics for the enlargement countries, in other words the candidate countries and potential candidates. Montenegro, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Albania, Serbia and Turkey currently have candidate status, while Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo [1] are potential candidates.

The article provides finance statistics in relation to a range of topics, including government finance (such as the general government deficit/surplus and government debt relative to GDP), foreign direct investment (FDI), the money supply, consumer price indices, interest and exchange rates.

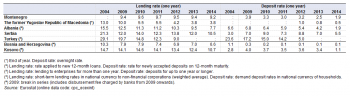

(% of GDP)

Source: Eurostat (gov_10dd_edpt1) and (cpc_ecgov)

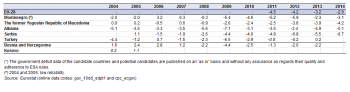

(% of GDP)

Source: Eurostat (gov_10dd_edpt1) and (cpc_ecgov)

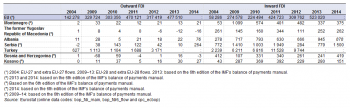

(million EUR)

Source: Eurostat (bop_fdi_main), (bop_fdi6_flow) and (cpc_ecbop)

(million EUR)

Source: Eurostat (cpc_ecmny) and the European Central Bank

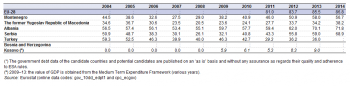

(% change relative to the previous year)

Source: Eurostat (prc_hicp_aind) and (cpc_ecprice)

(1 euro = … national currency)

Source: Eurostat (cpc_ecexint)

Main statistical findings

Government deficits and debt

The general government deficit of the EU-28 partly recovered from the global financial and economic crisis, such that it stood at -2.93 % of GDP in 2014

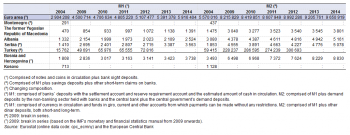

The global financial and economic crisis triggered a sharp downturn in public finances across Europe and many countries continue to struggle to reduce their public deficits. The general government deficit of the EU-28 had reached -4.5 % of GDP by 2011 and narrowed over the next few years to reach -2.9 % of GDP by 2014 (see Table 1).

Most of the enlargement countries recorded government deficits during the period 2008–14

In 2007, three of the enlargement countries (Albania, Serbia and Turkey) ran a government deficit, while the other three enlargement countries for which data are available (no information for Kosovo) posted surpluses of between 0.6 % of GDP in the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia and 6.3 % of GDP in Montenegro.

This situation changed abruptly in 2008 with the onset of the financial and economic crisis; all of the enlargement countries recorded a government deficit. This pattern continued and the deficit (relative to GDP) of each enlargement country widened in 2009. Between 2009 and 2012, the enlargement countries continued to record government deficits. In 2013, the situation changed as Turkey reported a surplus (0.2 %). In 2014, the only countries to report that their latest deficit was wider than in 2009 were the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia and Serbia.

The general government debt of the EU-28 continued to rise and reached 86.8 % of GDP by 2014

General government debt across the EU-28 stood at 81.0 % of GDP in 2011, reflecting a sharp rise during the financial and economic crisis. This ratio continued to rise in subsequent years and reached 86.8 % of GDP by 2014 (see Table 2).

Government debt among the enlargement countries represented between one third and three quarters of GDP, a lower proportion than in the EU

In 2008, at the onset of the financial and economic crisis, the ratio of general government debt-to-GDP in the enlargement countries ranged from 20.5 % in the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia to 55.1 % in Albania; note that there are no data available for Bosnia and Herzegovina for this indicator, while Kosovo reported no debt prior to 2009.

Government debt (relative to GDP) increased in 2009 in each of the enlargement countries, although developments thereafter were more mixed. The latest data available for 2014 show that government debt-to-GDP ratios were lower — sometimes considerably so — across the enlargement countries than in the EU-28, ranging from just below 40 % in Turkey (2013 data) and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia to highs of 68.9 % in Serbia and 71.8 % in Albania.

Foreign direct investment

Outward flows of FDI from the EU-28 to non-member countries reached EUR 478 billion in 2013

Flows of foreign direct investment (FDI) result from investors building up or reducing their assets abroad by investing in or disinvesting from foreign companies. Flows of FDI are notoriously erratic (with big changes from one year to the next as investment decisions are often lumpy). With the onset of the global financial and economic crisis it is perhaps unsurprising to find that FDI flows fluctuated considerably. Outward investment from the EU-28 (into non-member countries) stood at EUR 330 billion in 2009 and remained relatively low in 2010 before an expansion in 2011 and a similarly sized contraction in 2012. In 2013, flows of FDI were valued at EUR 478 billion; note that for the 2013 data a new methodology has been implemented.

The value of FDI flows coming into the EU from non-member countries was consistently lower than the value of outward FDI during the period 2009–12. However, this pattern was reversed in 2013, as inward flows of FDI in 2013 exceeded outward flows by EUR 46 billion (see Table 3).

The level of outward FDI from enlargement countries was considerably lower than that recorded for the EU. Furthermore, some of the enlargement countries recorded negative flows of outward FDI, in other words, disinvestment, which occurs when previous investments are withdrawn from foreign enterprises (perhaps to consolidate their operations in domestic markets). In absolute terms, the only substantial outward flow of FDI from an enlargement country was in relation to FDI from Turkey, some EUR 3.2 billion in 2012.

Inward foreign direct investment played a considerable role in some of the enlargement countries

Each of the enlargement countries had a higher level of FDI inflows than outflows; in other words, each of these countries was a net recipient of FDI. Together the enlargement countries had a combined level of inward FDI valued at EUR 11.8 billion in 2012 (the latest year for which data for all countries is available); this equated to 3.8 % of the inward FDI into the EU-28 in the same year. Turkey was by far the largest beneficiary of inward FDI among the enlargement countries in absolute terms, accounting for more than four fifths (82.7 %) of the total in 2012.

However, inward flows of FDI played a considerable role in some of the smaller enlargement economies. This was particularly the case in Albania and Montenegro, where the ratio of inward FDI to GDP peaked at 8.8 % and 7.0 % respectively in 2014. At the other end of the range, inward FDI in Turkey represented 1.6 % of GDP in 2012, which was the lowest ratio among any of the enlargement countries.

In an increasingly globalised world it is unsurprising to find that there was a considerable increase in the value of FDI flows over the most recent 10-year period for which data are available. There was rapid growth in the value of inward FDI in the majority of the enlargement countries, the exceptions being Bosnia and Herzegovina and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia where the level of inward FDI was approximately the same in 2014 as it had been in 2004. By contrast, inward FDI in Albania, Kosovo, Turkey and Montenegro was three to seven times as high in 2014 (2012 data for Turkey) as it had been in 2004.

Money supply

The money supply may be simply described as the circulation of money within an economy. There are various measures of money supply and these are differentiated by the liquidity of the assets under consideration (see Table 4). The narrowest definition is M1, which measures the cash and coins in circulation, plus the value of current accounts. M2 is a somewhat broader concept, including M1, plus savings deposits, money market mutual funds and other time deposits — which are less liquid — but may nevertheless be relatively quickly converted into cash or sight deposits.

As may be expected, the amount of money in circulation varies according to the size of each economy, with the money supply in Turkey considerably larger than in any of the other enlargement countries. Turkey also recorded the fastest expansion in its money supply since 2004. Note that there is no data for the money supply covering recent reference periods in Montenegro or Kosovo as they use the euro as their de facto domestic currency.

Generally, if the money supply rises faster than economic growth, then inflationary pressures will be added to the economy. However, in the aftermath of the financial and economic crisis, the process of quantitative easing was used by several central banks in order to inject additional quantities of money into their banking systems with the goal of encouraging growth; evidence so far suggests that this process did not result in inflationary pressures (see Table 5).

Consumer prices

Consumer price growth within the EU was below 2.0 % in both 2013 and 2014

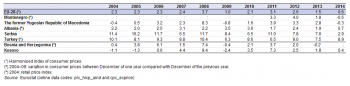

The all-items harmonised index of consumer prices remained at relatively low levels across the EU during the period 2004–14. The rate of annual price increases peaked at 3.7 % in 2008, although the effects of the financial and economic crisis caused a rapid slowdown in price increases in 2009 when a relative low of 1.0 % was recorded. Thereafter, prices in the EU rose by 2.1 % in 2010 and by 3.1 % in 2011, before the pace of price increases slowed in 2012, 2013 and 2014, when consumer prices in the EU-28 rose by 2.6 %, 1.5 % and 0.6 % respectively (see Table 5).

Highest price increases among the enlargement countries recorded in Serbia and in Turkey

Consumer price increases in the enlargement countries over the period 2004–14 were generally higher than those recorded across the EU; this could, at least in part, be attributed to the deregulation of prices which formed part of the liberalisation process undertaken in several enlargement economies. Following a relative peak in 2008, in most of the enlargement countries prices rose at a relatively slow pace in 2009, before accelerating somewhat in 2010 and 2011 and then returning to more modest increases in 2013 and 2014.

The latest information available for each of the enlargement countries shows that consumer price increases in 2014 remained in single-digits. Serbia (2.9 %) and Turkey (8.9 %) continued to record price increases that were higher than those for the other enlargement countries. Elsewhere, price increases peaked at 0.7 % in Albania and price decreases were reported in Montenegro and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia in 2014.

Interest rates

Interest rates equate to the cost charged/paid for the use of money; they are generally expressed as an annual percentage rate (APR). The lending rate is the rate charged by banks on loans to their prime customers: if the borrower is a low-risk party, they will usually be charged a lower interest rate. The deposit rate is the rate paid by commercial or similar banks for demand, time, or savings deposits: larger deposits or deposits for lengthier periods of time will generally attract higher interest payments.

Table 6 shows the variation in lending rates between the enlargement countries; it is important to note that different definitions apply to some of the countries. Aside from the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia where lending rates were particularly low (3.8 % in 2014), the latest information available shows that rates ranged from 6.6 % in Bosnia and Herzegovina to 10.7 % in Kosovo. During the period 2004–14 there was generally a pattern of falling lending rates. Indeed, each of the enlargement countries recorded their lowest lending rate for the most recent period for which data are available (2014 for all countries, except Turkey (2012 data)).

This pattern was reproduced when analysing the development of deposit rates since the onset of the financial and economic crisis, as deposit rates fell between 2009 and 2014 in each of the enlargement countries (the latest rates for Turkey refer to 2012). Deposit rates varied from 0.1 % in Bosnia and Herzegovina to 5.5 % in Serbia in 2014. The spread in rates (the difference between lending rates and deposit rates) was just over 3 percentage points in the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, and generally stood between 5 and 7 percentage points, other than in Kosovo (9.6 points difference).

Exchange rates

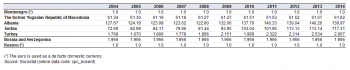

Market-based exchange rates reflect the rate at which one currency is exchanged for another. Table 7 presents exchange rates for the enlargement countries in relation to the euro; note that while Montenegro and Kosovo are neither EU Member States, nor members of the euro area, they do use the euro as their de facto domestic currency (and as such their exchange rates are set in the table at parity). Note also that Bosnia and Herzegovina maintains a unilaterally fixed exchange rate against the euro and that the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia has pegged its domestic currency to the euro (explaining the low or lack of fluctuation in their exchange rates).

As such, there were only three enlargement countries which had floating exchange rates against the euro during the period 2004–14. Each of these saw the value of their currency depreciate: the Albanian lek depreciated by 9.6 %, while exchange rate fluctuations against the euro were more marked for Turkey and Serbia, the Turkish lira depreciating by 64.4 % and the Serbian dinar by 61.4 % between 2004 and 2014.

Data sources and availability

Data for the enlargement countries are collected for a wide range of indicators each year through a questionnaire that is sent by Eurostat to partner countries which have either the status of being candidate countries or potential candidates. A network of contacts in each country has been established for updating these questionnaires, generally within the national statistical offices, but potentially including representatives of other data-producing organisations (for example, central banks or government ministries). The statistics shown in this article are made available free-of-charge on Eurostat’s website, together with a wide range of other socio-economic indicators collected as part of this initiative.

The European system of national and regional accounts (ESA) provides the methodology for national accounts and government statistics in the EU. Under the terms of the excessive deficit procedure (EDP), EU Member States are required to provide the European Commission with their government deficit and debt statistics before 1 April and 1 October of each year. From October 2014 onwards, candidate countries (but not potential candidates) were asked to report EDP-related data to Eurostat with the same frequency as EU Member States.

The general government sector includes all institutional units whose output is intended for individual and collective consumption and mainly financed by compulsory payments made by units belonging to other sectors, and/or all institutional units principally engaged in the redistribution of national income and wealth. The public balance is defined as general government net borrowing/net lending reported for the excessive deficit procedure and is expressed in relation to GDP. Government debt is the gross debt outstanding at the end of the year of the general government sector measured at nominal (face) value and consolidated.

Tables in this article use the following notation:

| Value in italics | data value is forecasted, provisional or estimated and is therefore likely to change; |

| : | not available, confidential or unreliable value. |

| – | not applicable. |

Context

The financial and economic crisis resulted in serious challenges being posed to many European governments. The main concerns were linked to the ability of national administrations to be able to service their debt repayments, take the necessary action to ensure that their public spending is brought under control, while at the same time trying to promote economic growth.

Within the EU, multilateral economic surveillance was introduced through the stability and growth pact (SGP) which provides for the coordination of fiscal policies. Under the terms of the SGP, Member States pledged that their government deficit would not exceed 3 % of gross domestic product (GDP), while their debt would not exceed 60 % of GDP. Indeed, the disciplines of the SGP are intended to keep economic developments in the EU, and the euro area countries in particular, broadly synchronised. Furthermore, the SGP is designed to prevent EU Member States from taking policy measures which would unduly benefit their own economies at the expense of others. The latest revision of the integrated economic and employment guidelines (revised as part of the Europe 2020 strategy) includes a guideline to ensure the quality and the sustainability of public finances.

Economic and financial statistics have become one of the cornerstones of governance at a global and European level, for example, to analyse national economies during the financial and economic crisis or to put in place EU initiatives such as the European semester or macroeconomic imbalance procedures (MIP). Indeed, these policies are central to the Europe 2020 strategy which seeks to turn the EU into a smart, sustainable and inclusive economy.

While basic principles and institutional frameworks for producing statistics are already in place, the enlargement countries are expected to increase progressively the volume and quality of their data and to transmit these data to Eurostat in the context of the EU accession process. The EU standards in the field of statistics require the existence of a statistical infrastructure based on principles such as professional independence, impartiality, relevance, confidentiality of individual data and easy access to official statistics; they cover methodology, classifications and standards for production.

Eurostat has the responsibility to ensure that statistical production of the enlargement countries complies with the EU acquis in the field of statistics. To do so, Eurostat supports the national statistical offices and other producers of official statistics through a range of initiatives, such as pilot surveys, training courses, traineeships, study visits, workshops and seminars, and participation in meetings within the European statistical system (ESS). The ultimate goal is the provision of harmonised, high-quality data that conforms to European and international standards.

Additional information on statistical cooperation with the enlargement countries is provided here.

See also

- Enlargement countries — statistical overview — online publication

- Statistical cooperation — online publication

Further Eurostat information

Publications

- Pocketbooks

- Key figures on the enlargement countries — 2014 edition

- Key figures on the enlargement countries — 2013 edition

- Leaflets

Database

- Economy and finance (cpc_ec)

- Government finance statistics (ENP and ESA2010) (gov_gfs10)

- Annual government finance statistics (gov_10a)

- Government deficit and debt (gov_10dd)

- Harmonised indices of consumer prices (prc_hicp)

- HICP (2005 = 100) — annual data (average index and rate of change) (prc_hicp_aind)

- European Union direct investments (bop_fdi)

- European Union direct investments (BPM6) (bop_fdi6) (Overview)

Dedicated section

Methodology / Metadata

- Candidate countries and potential candidates (ESMS metadata file — cpc_esms)

Source data for tables and figures (MS Excel)

External links

- Europe 2020

- Europe 2020 — Jobs, growth and investment

- European Commission — Economic and financial affairs

- European Commission — Economic and financial affairs — stability and growth pact

- European Commission — Enlargement

- IMF: sixth edition of the balance of payments manual

Notes

- ↑ This designation is without prejudice to positions on status, and is in line with UNSCR 1244 and the ICJ Opinion on the Kosovo Declaration of Independence.