Personal transfers and compensation of employees

Data extracted in December 2023

Planned article update: 12 December 2024

Highlights

(% of GDP)

Source: Eurostat (bop_rem6), (nama_10_gdp)

This article presents statistics and comments on recent developments relating to resource flows benefitting households in the European Union (EU) and the rest of the world. It refers in particular to personal transfers (i.e. transfers sent by resident migrants to their home economies) and gross compensation of employees from seasonal-, short-term-, and cross-border workers according to the concept of the 6th Edition of the IMF Balance of payments and international investment position manual (BPM6). Data on these two standard components of balance of payments statistics provide an interesting picture on potentially important sources of external funding that contribute to GNI and disposable income of the recipient countries. The data situation currently does not allow for producing "personal remittances" according to the BPM6. Please refer to the CONTEXT section below and to Remittances according to the BPM6 manual for more information.

Full article

The EU remained a net sender of personal transfers and net receiver of employees’ compensation in 2022

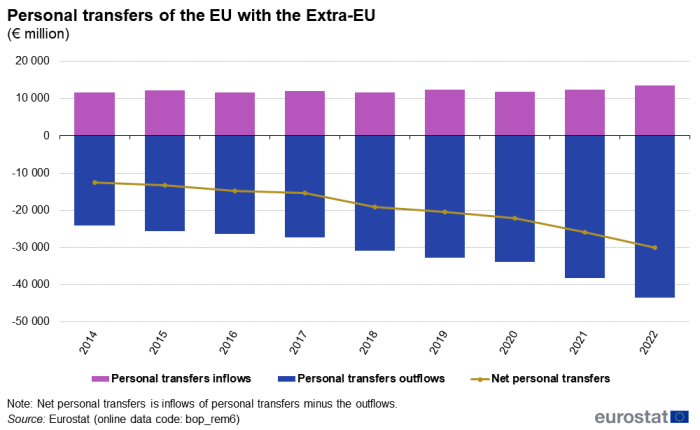

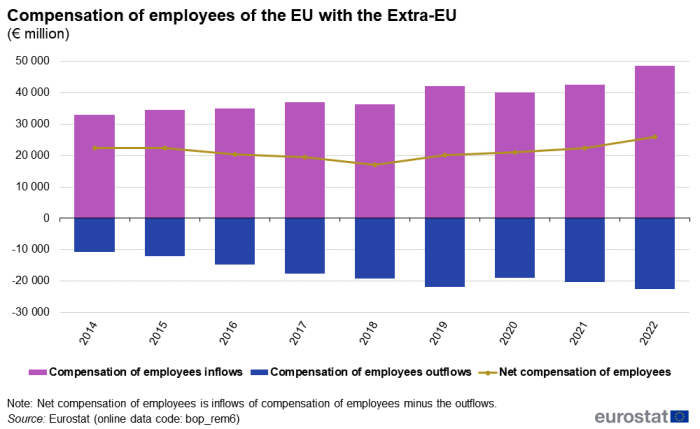

In the context of the EU, the respective net of outflows minus inflows of personal transfers and compensation of employees with the rest of the world generally occurs with opposite signs. Outflows of personal transfers from the EU to the rest of the world are higher than inflows; at the same time, EU employees earned more compensation outside of the EU than nonresidents in the EU, resulting in larger inflows than outflows (Figures 1a and 1b).

(€ million)

Source: Eurostat (bop_rem6)

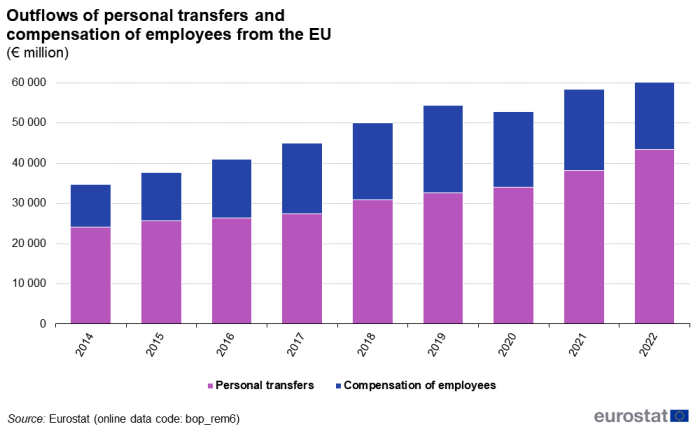

Personal transfers kept dominating outflows from the EU…

After continuous growth since 2014, net outflows of personal transfers and compensation of employees fell for the first time in 2020 but then increased again considerably to a record level of €66.1 billion in 2022 (Figure 2a). Outflows consist, to the largest part, of personal transfers sent abroad (in 2022: €43.5 billion).

(€ million)

Source: Eurostat (bop_rem6)

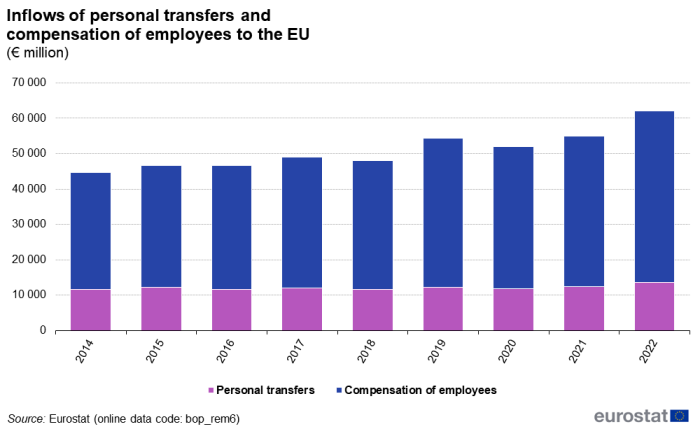

…while compensation of employees dominated inflows to the EU

Inflows of personal transfers and compensation of employees have been increasing at a slower pace since 2014, showed a drop in 2020, followed by increases again. The extent of inflows to the EU grew from €44.6 billion in 2014 to €62.0 billion in 2022. Inflows are mostly nurtured by compensation of employees received by EU border, seasonal or short-term workers contracted outside the EU (in 2022: €48.5 billion).

(€ million)

Source: Eurostat (bop_rem6)

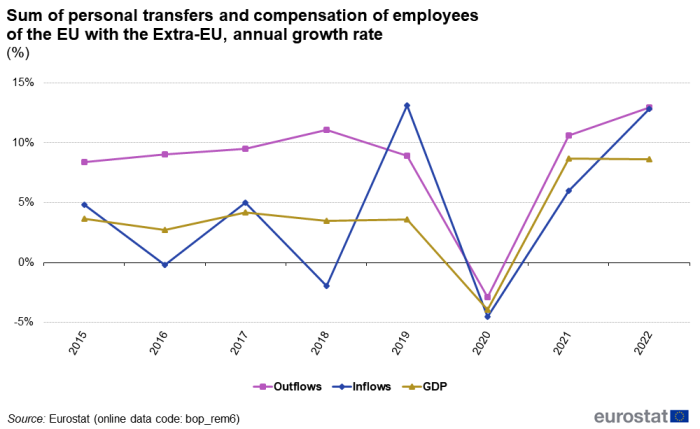

Growth rates plunged in 2020 but bounced back after

Between 2015 and 2019, the growth rate in outflows considerably exceeded annual growth in EU GDP seemingly indicating favorable labour market conditions for migrant, seasonal and cross border workers in the EU. Accordingly, outflows increased at an average annual growth rate of over 9.4 % in 2015-2019. Compared to outflows, inflows had a significant lower average growth rate of 4.2 %. In year 2020, marked by COVID-19 containment measures, growth rates for EU GDP (-3.9 %), outflows (-2.9 %) and inflows (-4.5 %) turned negative but bounced back to positive growth in 2021 and 2022. During this period the average outflows growth rate (11.8 %) kept above the ones for inflows (9.4 %) and EU GDP (8.7 %) (Figure 3).

(%)

Source: Eurostat (bop_rem6), (nama_10_gdp)

More than half of the amount of cross border compensation of employees and personal transfers remained within the EU

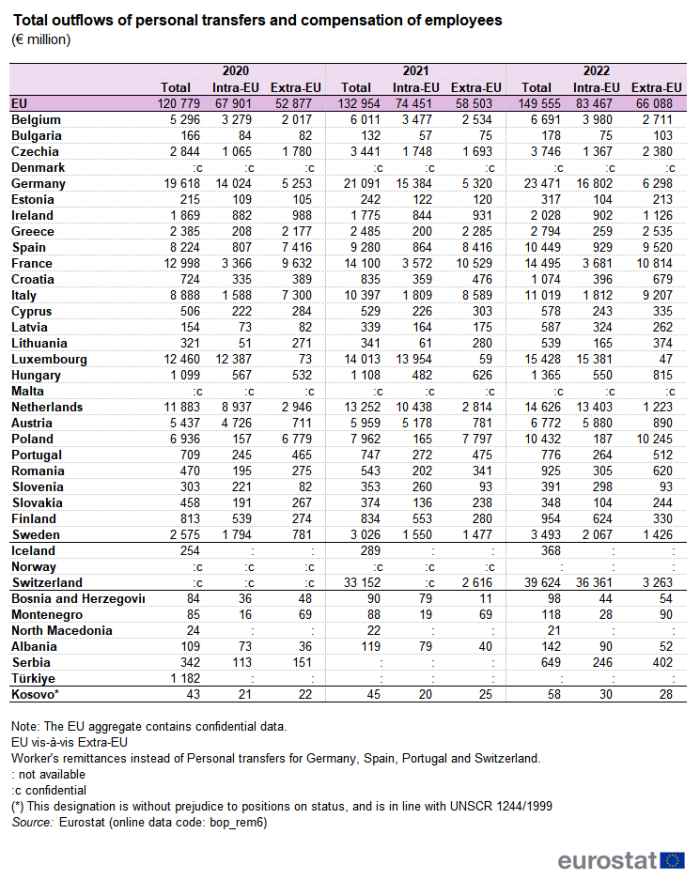

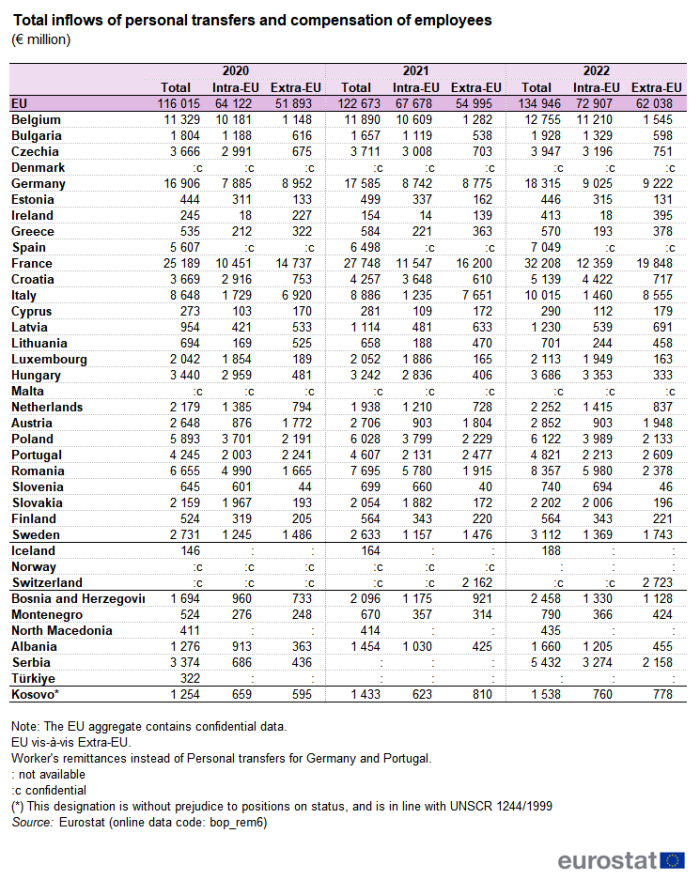

About 56 % of total outflows and 54 % of total inflows of all EU Member States’ cross- border personal transfer and compensation of employee flows in 2022 took place within the borders of the EU. This does not come as a surprise given that EU citizens can move and work freely within the EU labour market. There are, however, exceptions: outflows of personal transfers and compensation of employees from Poland (98 %), Spain (91 %) and Greece (91 %) went predominantly to economies outside of the EU; while also Ireland (96 %), Italy (85 %), and Austria (68 %) received their inflows mostly from outside the EU. The most EU-centered economies were Luxembourg with less than 1 % of its outflows recorded to beyond the EU, and Slovenia with only 6 % of its inflows received from outside the EU (see Tables 1 and 2).

(€ million)

Source: Eurostat (bop_rem6)

(€ million)

Source: Eurostat (bop_rem6)

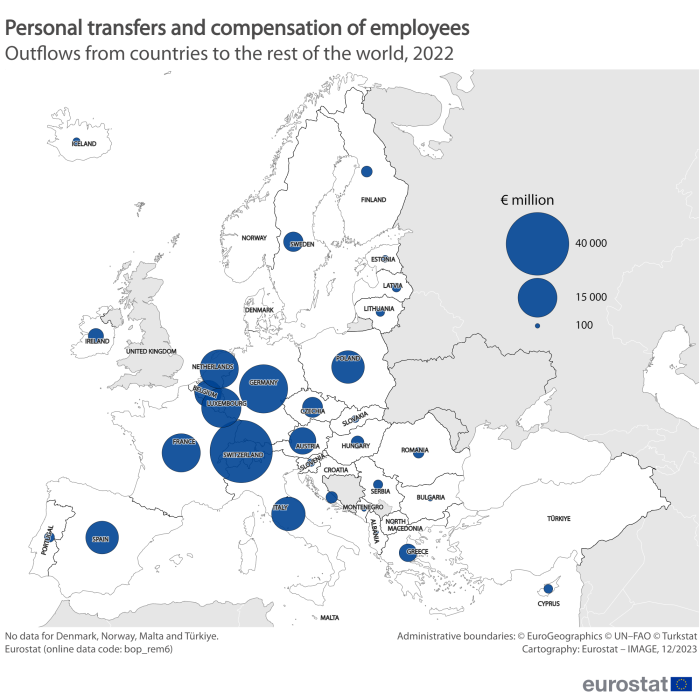

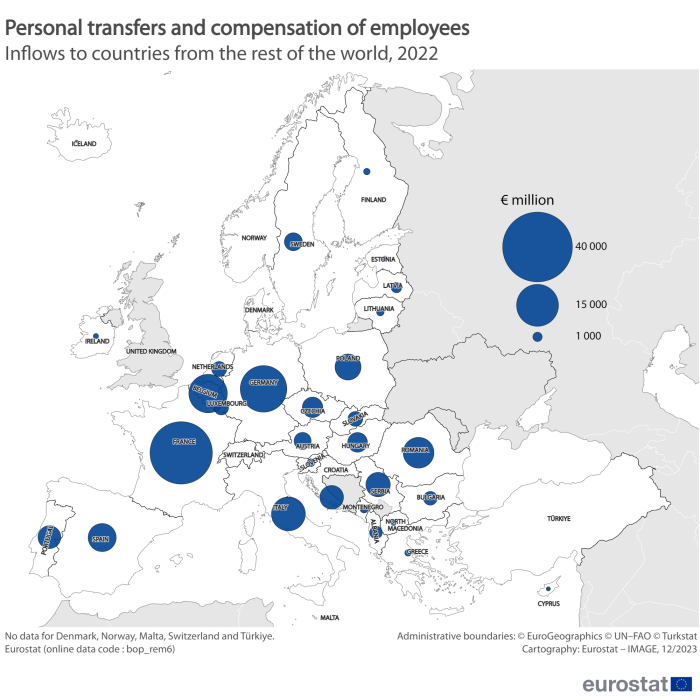

Western European countries were amongst the main senders and recipients of these cross-border flows

In absolute terms, the major economies contributing to outflows of personal transfer and compensation of employees' flows (intra-EU plus extra-EU) in 2022 were Germany (16 % of total outbound flows of all EU Member States), Luxembourg (10 %), the Netherlands (10 %), and France (10 %). Outgoing flows from Germany, Luxembourg and the Netherlands predominantly originated from income generated through border, seasonal or short-term work in these countries, while outflows in France mainly derived from personal transfers sent abroad.

The major recipient economies of personal transfers and compensation of employee funds (inflows from intra-EU plus extra-EU) in 2022 were France (24 % of total inbound flows of all EU Member States), Germany (14 %) and Belgium (9 %); all predominantly based on income generated through border, seasonal and short-term work by their residents abroad (see Maps 1a and 1b).

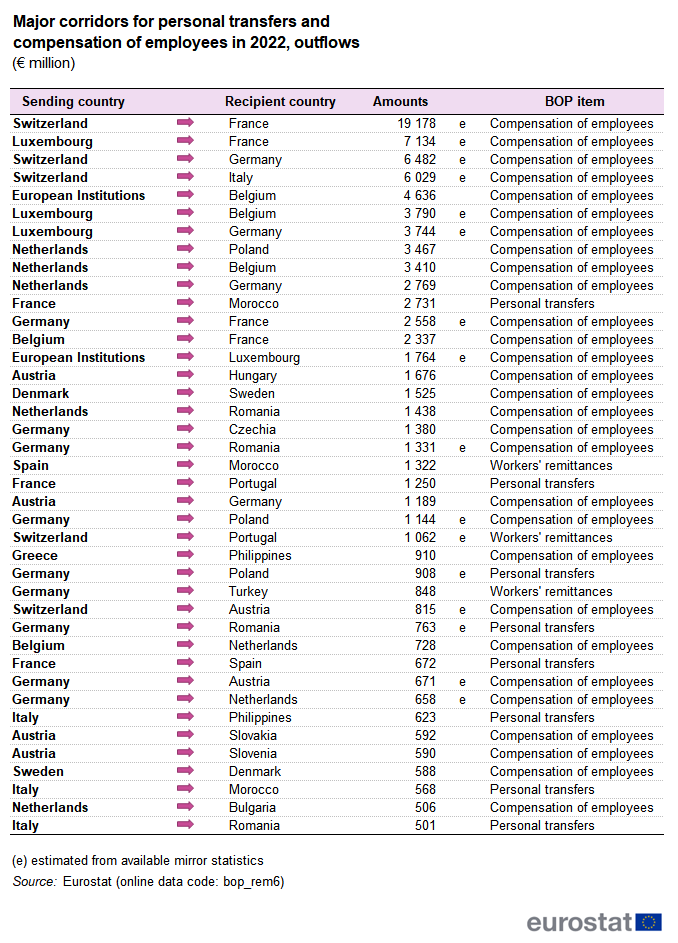

Zooming in, cross-border personal transfers and income flows can be analyzed in a bilateral context, in which geographical proximity could play an important role. For instance, in 2022, France observed major corridors with all its neighbouring countries representing significant inflows, most notably from French residents’ border and seasonal work in Switzerland (€19.2 billion)[1], and Luxembourg (€7.1 billion); while France recorded the highest outflows of personal transfers to Morocco (€2.7 billion). In a similar manner, Germany (with Switzerland €6.5 billion), Italy (with Switzerland €6.0 billion), and Belgium (with Luxembourg €3.8 billion) benefited from their neighbouring countries in terms of border and seasonal work relationships, while Belgium and Luxembourg also recorded significant inflows from the European Institutions domiciled in their jurisdictions (Belgium €4.6 billion, Luxembourg €1.8 billion).

Beyond the limits of geographical proximity, the Netherlands was the major source of income for seasonal workers from Poland (€3.5 billion), while for personal transfers Portugal received almost €1.3 billion from France. Regarding transactions of EU Member States with Asia, Greece recorded significant outflows of compensation of employees to the Philippines (€0.9 billion).

A major attractive location for employment of EU citizens outside the EU was Switzerland, generating considerable outflows in compensation of employees to the EU for France (€19.2 billion), Germany (€6.5 billion), Italy (€6.0 billion), as well as for Portugal (€1.1 billion) and Austria (€0.8 billion)[2]. These countries benefitted significantly from their residents working in Switzerland. Poland (€0.9 billion) and Türkiye (€0.8 billion) were in 2022 the major receivers of personal transfers from Germany.

(€ million)

Source: Eurostat (bop_rem6)

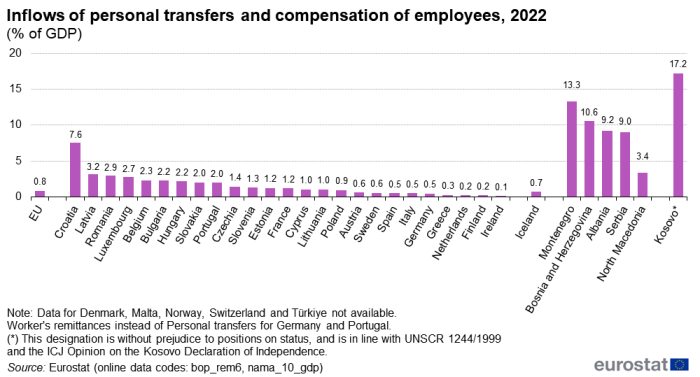

Among Member States, Croatia, Latvia and Romania were most dependent on personal transfer and compensation of employees inflows in 2022

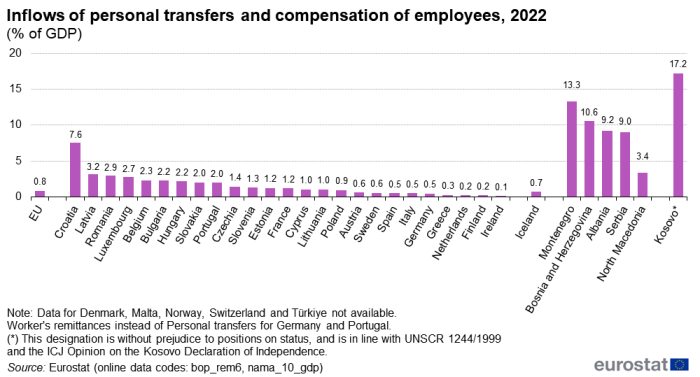

Dependency rates are measured by showing the share of inflows in personal transfers and compensation of employees in relation to a respective country's GDP. According to this, the highest dependency rates in the EU were observed for Croatia (7.6 % of GDP), Latvia (3.2 % of GDP) and Romania (2.9 % of GDP) in 2022 (see Figure 4), while the least reliant economies in the EU were Ireland (less than 0.1 % of GDP), Finland and the Netherlands (each 0.2 % of GDP). By comparison, southeastern non-EU countries appeared much more dependent on this source of income: Kosovo[3] (17.2 % of GDP), Montenegro (13.3 % of GDP), and Bosnia and Herzegovina (10.6 % of GDP)[4].

(% of GDP)

Source: Eurostat (bop_rem6), (nama_10_gdp)

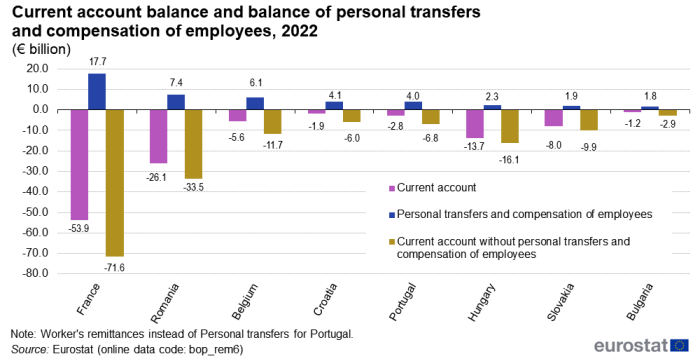

For France, Romania and Belgium the positive net balance of personal transfers and compensation of employees reduces their current account deficits significantly

For some countries, net inflows of personal transfers and compensation of employees are important sources of external funding and contributors to a recipient’s disposable income and GNI.

In 2022, France, Romania and Belgium could considerably reduce their negative current account balances through these net inflows (see Figure 5). Most prominently, France showed a current account deficit of €53.9 billion; without these net incoming flows, this deficit would have considerably increased to €71.6 billion. Responsible for this reduction was mostly the net income generated in Switzerland, Luxembourg, and Germany. The current account deficit for Romania would have been €33.5 billion instead of €26.1 billion which includes transactions related to personal transfers and compensation of employees. Belgium exhibited a current account deficit of €5.6 billion, which would have widened to €11.7 billion without net compensation of Belgian employees’ working for EU institutions (€4.6 billion) and for institutional units in Luxembourg (€3.8 billion).

(€ million)

Source: Eurostat (bop_rem6), (bop_c6_a)

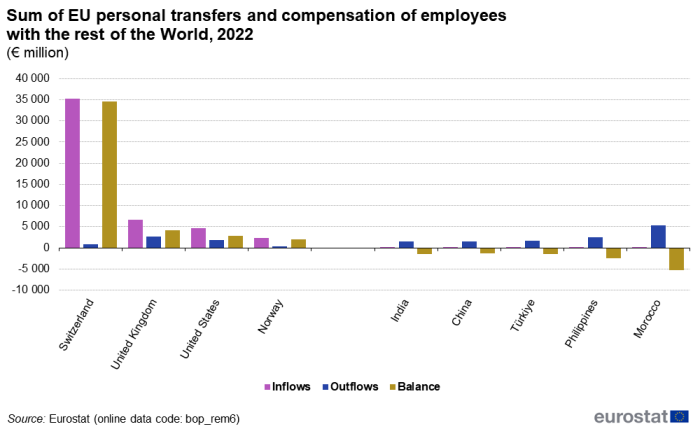

Total EU net inflows were dominated by Switzerland while net outflows spread among many countries

By far the highest surplus in 2022 in personal transfers and compensation of employees, €34.5 billion, the EU recorded vis-à-vis Switzerland, mostly due to compensation of employees flows to France, Germany and Italy. It was followed by the United Kingdom, with a surplus of €4.1 billion, mostly due to personal transfers to Romania and to personal transfers and compensation of employees to Poland [5]. The EU recorded also a considerable surplus of €2.8 billion with the United States where personal transfers contributed €1.6 billion. The balance surplus of €1.9 billion with Norway was mostly achieved due to compensation of employees’ inflows to Sweden. However, overall, the EU had a net deficit vis-à-vis the rest of the world when adding up all total inflows and outflows for personal transfers and compensation of employees. Major net outflows in 2022 were recorded with Morocco (€5.2 billion), the Philippines (€2.5 billion), Türkiye and India (each €1.5 billion), China (€1.3 billion). Net outflows to Morocco, Türkiye and India were based on personal transfers, while those to the Philippines and China resulted from both personal transfers and compensation of employees. (Figure 6).

(€ million)

Source: Eurostat (bop_rem6)

Data sources

Data on incoming and outgoing personal transfers [6] and compensation of employee flows according to the BPM6 are available from dedicated tables (bop_rem6) in the Eurostat database under the balance of payments domain, with the most comprehensive coverage starting from 2005. The online tables are available for each component on an annual basis and are reported by Member States by end-September each year with an extended geographical breakdown (Geo 5 – main world aggregates and a large selection of countries). The EU aggregates also contain confidential data as well as Eurostat estimations for missing data. Eurostat regularly collects quarterly data on personal transfers and compensation of employees but with fewer geographical details. All disseminated data are subject to revisions.

Context

Data on personal transfers and compensation of employees are collected based on Regulation (EC) No. 184/2005 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 January 2005 on Community statistics concerning balance of payments, international trade in services and foreign direct investment.

The data situation currently does not allow the production of figures on so-called "personal remittances". Personal remittances is a BPM6 concept that derives from the following components. From the viewpoint of the recipient country (inflows):

Personal transfers receivable

+ Compensation of employees receivable

- Taxes and social contributions payable (related to compensation of employees)

- Transport and travel expenditures payable by residents employed by nonresidents (as defined under business travel in BPM6 paragraphs 10.91–10.93)

+ Capital transfers receivable from households.

From these components, only the standard components of personal transfers and (gross) compensation of employees are currently available[7].

The reason for incomplete data on personal remittances lies in the considerable information asymmetries between host and recipient economies and the relative insignificance of remittance flows in industrial nations in their role as host economies. For recipient economies abroad, they often represent, however, a substantial source of income (see above measures in relation to GDP and current account balance). Furthermore, the heterogeneous character of remittance transactions makes the compilation process more complex as countries usually rely on a combination of resources (data collections from the financial sector, surveys on migrant or commuter populations, estimations based on macroeconomic modelling). Additionally, many remittance flows take place through unofficial channels[8].

Bilateral discrepancies are the consequence when analysing intra-EU flows, i.e. personal transfer and compensation of employee flows between the Member States of the EU. In theory, intra-EU inflows (credits) should equal mirror intra-EU outflows (debits). Asymmetries, calculated as intra-EU inflows (credits) minus intra-EU outflows (debits), show positive values for personal transfers and mostly negative values for compensation of employees. It is often the case that personal transfers are more relevant for beneficiary countries and thus credits are higher (and presumably of better quality), while for compensation of employees, debit data are easier to compile as they are available from administrative sources.

Users should keep in mind these shortcomings when analysing the data. The use of macroeconomic modelling has certainly increased knowledge about these international flows and can address - to some extent - the problem of under-coverage.

In view of the large movements of refugees and migrants in recent years, a renewed interest on international remittances in the context of migration evolves among European policy-makers, emphasizing the significant impact of remittances and resource flows on developing economies. For a snapshot on migration and remittances from a global perspective, the World Bank publishes, on a regular basis, valuable updates on recent trends and migrations[9][10], as well as annual estimates of personal remittances under its World Development Indicators.

Direct access to

- Personal transfers and compensation of employees (bop_rem6)

- Regulation (EU) No. 1013/2016 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 8 June 2016 on Community statistics concerning balance of payments, international trade in services and foreign direct investment

- Regulation (EC) No.184/2005 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 January 2005 on Community statistics concerning balance of payments, international trade in services and foreign direct investment.

- Summaries of EU Legislation: EU statistics — balance of payments, trade in services and foreign direct investment

- Commission Regulation (EU) No.555/2012 of 22 June 2012 amending Regulation (EC) No.184/2005 of the European Parliament and of the Council on Community statistics concerning balance of payments, international trade in services and foreign direct investment, as regards the update of data requirements and definitions.

Notes

- ↑ Due to the unavailability of Swiss data, this figure was derived from inbound flows reported by France.

- ↑ Due to the unavailability of Swiss data, figures were derived from inbound flows reported by France, Germany, Italy, Portugal and Austria.

- ↑ This designation is without prejudice to positions on status, and is in line with UNSCR 1244/1999 and the ICJ Opinion on the Kosovo declaration of independence.

- ↑ Source: Eurostat

- ↑ Due to the unavailability of data from the United Kingdom, main counterpart countries were derived from inbound flows reported by Romania and Poland.

- ↑ In some countries the memo item workers' remittances is available instead of personal transfers

- ↑ For more details see in Eurostat Statistics Explained Remittances according to the BPM6 manual

- ↑ What Are Remittances? (imf.org)

- ↑ Trends in Migration and Remittances 2017, World Bank

- ↑ Migration and remittances