Archive:Population change at regional level

Demographic trends have a strong impact on the societies of the European Union (EU). Consistently low fertility levels, combined with an extended longevity and the fact that the baby boomers are reaching retirement age, result in a demographic ageing of the EU population. The share of the older generation is increasing, while the share of those of working age is decreasing. This article presents the regional pattern of demographic phenomena as it is visible today.

Main statistical findings

The drivers behind population change

During the last four and a half decades, the population of the 27 countries of today’s European Union (EU-27) has grown from around 400 million persons (1960) to almost 500 million persons (2007). However, the strength and composition of the population growth have varied significantly over the years.

The total population change has two components: the so-called ‘natural increase’, which is defined as the difference between the numbers of live births and deaths, and net migration, which ideally represents the difference between inward and outward migration flows. Until the end of the 1980s, the natural increase was by far the major component of population growth. However, since the early 1960s there has been a sustained decline in the natural increase.

International migration, on the other hand, has gained in importance, becoming the major force of population growth from the beginning of the 1990s onwards.

Maps 1, 2 and 3 show the total population change and its components since the start of the new century. For the purposes of comparability, the population change is presented in relative terms, i.e. it is related to the size of the total population. The maps show the five-year average for the resulting ‘crude rates of population change’ (average for the years 2001 to 2005). In the north-east and east of the European Union the population is decreasing. Map 1 is marked by a clear divide between the regions there and in the rest of the EU. Most affected by a decreasing population are Germany, Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria, and to the north the three Baltic Member States, and parts of Sweden and Finland.

Map 2 shows that in many regions of the EU more persons have died than have been born since the start of the new century. The resulting negative ‘natural population change’ is widespread, although the pattern is less pronounced than for the total population change. Ireland, France and the three Benelux countries have been the main countries experiencing a natural increase in the population. The natural population change is predominantly negative in Germany, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Slovenia, Romania, Bulgaria and adjacent regions, as well as the Baltic Member States, Sweden in the north and Greece in the south. The other Member States have a situation that is, overall, more balanced.

A major reason for the slowdown of the natural increase in the population is the fact that, on average and over time, the inhabitants of the EU have fewer children. In the 27 countries that today form the European Union, the total fertility rate declined from a level of around 2½ in the early 1960s to a level of about 1½ in 1993, where it has remained (see Graph 1.1). The slight increase in recent years might be attributable in part to the fact that today more women are having their first child later in their lives. By comparison: In the more developed parts of the world, a total fertility rate of around 2.1 children per woman is currently considered to be the replacement level, i.e. the level at which a population would remain stable in the long run if there were no inward or outward migration. As for net migration, four cross-border regions where more persons have left than arrived can be identified on Map 3.

These are:

- the northernmost regions of Sweden and Finland;

- an eastern group, comprising most of eastern Germany, Poland, Lithuania and Latvia, as well as parts of the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria;

- regions in the north of France;

- regions in the south of Italy.

In some regions a negative ‘natural change’ has been compensated for by a positive net migration. This is most conspicuous in western Germany, eastern Austria and the north of Italy, as well as the south of Sweden and regions in Spain, Greece and the United Kingdom. The opposite is much rarer: in only a few regions (namely in the north of Poland) has a positive natural change been offset by negative net migration. Regions without compensation are often exposed to a profound development, upwards or — in some regions — downwards. In Ireland, the Benelux countries, many regions of France and some regions of Spain, a natural increase has been accompanied by positive net migration. However, in eastern Germany, Lithuania and Latvia, as well as some regions of Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria, both components of population change were negative. In some regions this has led to a sustained population loss.

Demographic ageing: the situation today ...

Age dependency ratios are important demographic indicators and relate the young and old age populations to the population of working age. The ‘old age’ roughly approximates to the age of retirement. Today, different demographic reports present dependency ratios based on different definitionsfor the age groups.

In this article the following age groups are used.

- Young age dependency ratio: the population aged up to 14 years related to the population aged between 15 and 64 years.

- Old age dependency ratio: the population aged 65 years or older related to the population aged between 15 and 64 years.

Maps 4 and 5 show the population structure at the beginning of 2006. The young age dependency ratio is influenced by recent fertility levels. Countries with higher fertility tend to have a higher young age dependency (i.e. more young people per 100 of working age) when compared with countries displaying low fertility levels. This is conspicuously the case for Ireland, France, the United Kingdom, the Benelux countries, Sweden and Finland. The young age dependency is below average in regions in Italy, Greece, Spain, Germany, the Czech Republic, Latvia, Romania and Bulgaria. The regional pattern for old age dependency is less clear cut.

... and its impact in the future

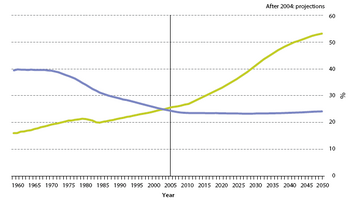

Eurostat’s population projections allow a fairly accurate anticipation of how the demographic situation will develop if current trends continue. The old age dependency ratio will be a particularly dynamic indicator. It is a reasonable projection that, on average for the EU-27 and if current trends prevail, the old age dependency ratio will approximately double during the next 50 years (Graph 2). This means that in 2050 a person of working age might have to provide for up to twice as many retired people as is usual today.

Demographic ageing is a general phenomenon. There are regions where, for a person aged 65 years or older, there are fewer than three persons of working age (old age dependency ratio of over 33 %). In 2006, this was still the exception; less than 6 % of the EU’s population lived in such regions. By 2026, however, this will be the rule (over three quarters of the EU population).

However, the regional differences that are already visible today might lead to a more dramatic development in some regions than in others. Map 6 highlights the size of the regional differences in the development. Whereas in some regions the increase in the old age dependency ratio between 2006 and 2026 will be well below 10 percentage points, the increase in other regions will be over 20 percentage points. In 13 regions, the old age dependency will rise to a level of around 50 % or more in 2026, which means that there will then be only two persons of working age for every person aged 65 years or over. Nine of these regions are in eastern Germany.

Data sources and availability

The analysis is mainly based on demographic trends that have been observed during the period from 1 January 2001 to 1 January 2006. For this purpose, five-year averages have been calculated of the total annual population change and of its components. Given that demographic trends are long-term developments, the five-year averages provide a stable and accurate picture. They help to identify regional clusters that often extend across national borders. Some demographic developments are likely to become considerably more important in future decades.

Eurostat calculates national and regional population projections that reveal the effects current trends might have if they continued into the future. Eurostat’s population projections should be considered not as forecasts, but as ‘what if?’ scenarios: they show possible demographic developments that are based upon assumptions about fertility, mortality and migration which, in turn, have been derived from observed trends and expert opinion.

The Eurostat population projections presented here correspond to the baseline variant of the trend scenario. The Eurostat set of population projections is just one of a number of scenarios of population evolution based on assumptions of fertility, mortality and migration. The current trend scenario does not take into account any future measures that could influence demographic trends.

It comprises different variants: the ‘baseline’ variant, plus ‘high population’, ‘low population’, ‘zero migration’, ‘high fertility’, ‘younger age profile’ and ‘older age profile’ variants, which are all available on the Eurostat website. It should be noted that the assumptions adopted by Eurostat may differ from those adopted by national statistical institutes. Therefore, the results may differ from those published by Member States. The regional breakdown of the population projections at NUTS level 2 is computed by making the assumptions already formulated for the national-level exercise into region-specific assumptions.

The regional variation in demographic behaviour is expressed using the method of indirect standardisation: the national fertility and mortality age- and sex-specific rates are applied first to the regional population, yielding a hypothetical number of events; subsequently, the observed number of regional events is divided by this hypothetical number to obtain a regional scaling factor. The latter is therefore an estimate of the extent to which regional rates are above or below the national value. For international migration, scaling factors were calculated as the ratio of the regional crude migration rate to the national crude migration rate. In addition to the traditional components (fertility, mortality and international migration), one issue that is peculiar to the regional dimension has to be considered: interregional migration. The age- and sex-specific rates of interregional migration are estimated by means of a model that uses as input the inter-NUTS 2 departures and arrivals by age, sex and region, and the total amount of inter-NUTS 2 migration by region of origin and region of destination (origin–destination migration matrix).

Owing to appropriate data not being available for France and the United Kingdom, regional population projections could not be made for these two countries. Source: Europop2004 regional level, baseline variant. Migration can be extremely difficult to measure. A variety of different data sources and definitions are used in the Member States, with the result that direct comparisons between national statistics can be difficult or misleading. The net migration figures here are not directly calculated from immigration and emigration flow figures. As many EU Member States do not have complete and comparable figures for immigration and emigration flows, net migration is estimated here as the difference between the total population change and the ‘natural increase’ over the year. In effect, net migration equals all changes in total population that cannot be attributed to births and deaths. The population density in this context is the ratio of the mid-year population of a territory to the size of the territory on a given date.

Context

Demographic evolution present and future poses huge challenges in all policy areas, ranging from education over labour market and economic performance to social conditions. The considerable regional differences make it highly important to obtain a view on a more detailed level.

Further Eurostat information

Publications

<links to Eurostat web site: downloadable publication(s); specifically and selectively, limited to at most 10>

Database

Eurostat website (under Data/Population/Population projections