Archive:Europe 2020 indicators - employment

- Data from October 2014. Most recent data:Further Eurostat information, Main tables.

This article is part of a set of statistical articles based on the Eurostat publication Smarter, greener, more inclusive? - Indicators to support the Europe 2020 strategy. It provides recent statistics on employment and other labour market-related issues in the European Union (EU), key areas of the EU's Europe 2020 strategy.

Paid employment is crucial for ensuring sufficient living standards and it contributes to economic performance, quality of life and social inclusion, making it one of the cornerstones of socioeconomic development and well-being.

The EU’s workforce, shrinking as a result of demographic changes, has to support a growing number of dependent people. This is a potential risk for the sustainability of Europe’s social model, welfare systems, economic growth and public finances, exacerbated by the recent economic crisis and intensifying global challenges and competition from developed and emerging economies.

Europe 2020 strategy target on employment The Europe 2020 strategy sets out a target of ‘increasing the employment rate of the population aged 20 to 64 to at least 75 %’ by 2020 [1].

(%)

Source: Eurostat online code (t2020_10)

(%)

Source: Eurostat online data code (2020_10)

(% of the population aged 20 to 64)

Source: Eurostat online data code (lfst_r_lfe2emprt)

(percentage points difference between 2013 and 2008, persons aged 20 to 64)

Source: Eurostat online data code (lfst_r_lfe2emprt)

(%)

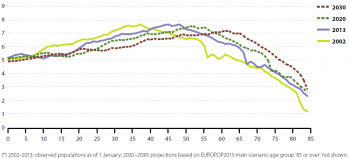

Source: Eurostat online data code (demo_pjan) and (proj_13npms)

(million persons)

Source: Eurostat online data code (demo_pjan) and (proj_13npms)

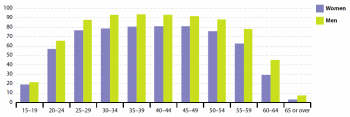

(%)

Source: Eurostat online data code (lfsa_pganws)

(%)

Source: Eurostat online data code (lfsa_pganws), (tsdde100)and (t2020_10)

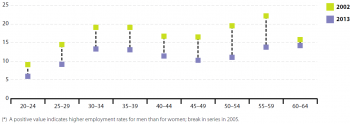

(difference between employment rates of men and women, in percentage points (*))

Source: Eurostat online data code (lfsa_ergan)

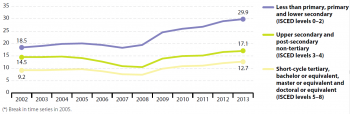

(%)

Source: Eurostat online data code (tsdec430)

(%)

Source: Eurostat online data code (yth_empl_090)

(%)

Source: Eurostat online data code (lfsa_ergan)

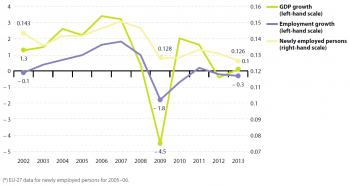

(left-hand scale: GDP growth and employment growth (percentage change over previous period)

(right-hand scale: newly employed persons (share of persons aged 20 to 64 whose job started within the past 12 months in total employment)

Source: Eurostat online data code (lfsi_grt_a) and (nama_gdp_k), European Commission services

(%)

Source: Eurostat online data code (bd_9bd_sz_cl_r2)

(Million full-time equivalent)

Source: Eurostat online data code (env_ac_egss1)

(%)

Source: Eurostat online data code (jvs_q_nace2), (jvs_q_nace1) and (une_rt_q)

Main statistical findings

Crisis brings rise in EU employment rate to a halt

The headline indicator ‘Employment rate — age group 20 to 64’ shows the share of employed 20 to 64 year olds in the total EU population.The reason for choosing this age group over the ‘usual’ working-age population 15 to 64 years old is explained in the section 'Data sources and availability'.

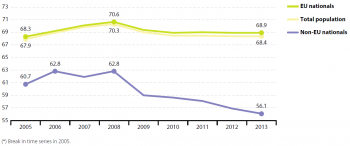

As indicated in Figure 1,the EU’s employment rate grew more or less steadily during the decade before the economic crisis, peaking at 70.3 % in 2008. In 2009, however, the crisis hit the labour market, knocking the employment rate back to the level of 2006. Employment in the EU continued to fall to 68.5 % in 2010 and further to 68.4 % in 2012, where it has remained since. As a result, in 2013 the EU was 6.6 per-centage points below the target value of 75 %.

North–South divide in employment rates across the EU

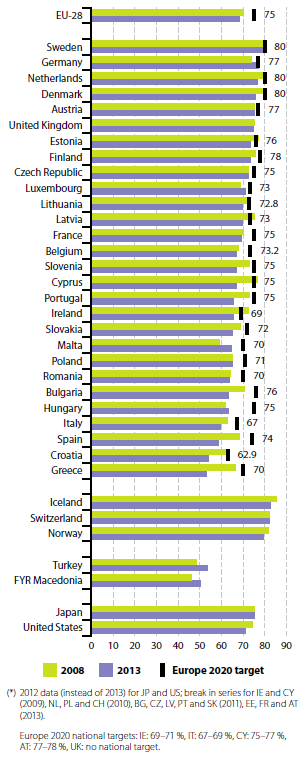

To reflect different national circumstances, the common EU target has been translated into national targets [2] (see Figure 3). These range from 62.9 % for Croatia to 80.0 % for Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden. In 2013, Germany had already met its national target, with an employment rate of 77.1 %. Of the remaining Member States, Sweden was closest at 0.2 percentage points below its national target. Greece and Spain were the most distant, at 17.1 and 15.4 percentage points below their national targets respectively.

Employment rates among EU Member States ranged from 52.9 % to 79.8 % in 2013. Northern and Central Europe had the highest rates, in particular Sweden, Germany, the Netherlands, Denmark and Austria. All of these countries exceeded the 75 % EU target. Countries at the lower end of the scale, with employment rates below 60 %, were Greece, Croatia, Spain and Italy. Rates in the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) countries Iceland, Norway and Switzerland tended to be higher than in the EU, while figures were lower in acceding countries. Employment rates in Japan and the United States were on the same level as the ‘top third’ of EU Member States, and above the EU-28 aggregate.

Over the past five years, employment has fallen in a majority of the EU countries; in 2013, employment rates in 22 Member States were below 2008 levels. This means these countries have still not fully recovered from the impacts of the crisis on their employment rates. The strongest falls were in Greece (– 13.4 percentage points), Spain (– 9.9 percentage points) and Cyprus (– 9.3 percentage points). The remaining six countries (Czech Republic, Germany, Luxembourg, Hungary, Malta and Austria) were back on a ‘growth path’ by 2013, meaning their employment rates were higher than before the economic crisis. Malta (5.6 percentage points) and Germany (3.1 percentage points) have experienced the strongest growth in employment rates since 2008.

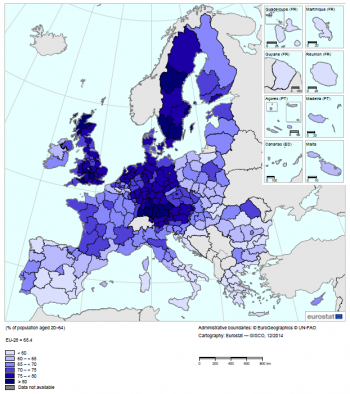

The variations in the employment rate across different Member States, depicted in Figure 3, are also reflected in the maps of cross-country regional distribution of employment rates (at NUTS 2 level). As shown in Map 1, the highest regional employment rates were predominantly recorded in North-western and Central Europe, particularly in Germany, the Netherlands, Austria, Sweden and the United Kingdom. In 2013, the Finnish region Åland had the highest employment rate in the EU, at 85.5 %, followed by Stockholm (Sweden) with 82.7 % and Freiburg (Germany) with 82.4 %. At the other end of the scale, the lowest employment rates were observed around the Mediterranean, in particular in the southern parts of Spain and Italy, and in Greece and Croatia, as well as in the French overseas regions and the outlying Spanish autonomous cities (Ceuta and Melilla). In 2013, the Italian regions Calabria, Sicilia and Campania had the lowest employment rates in the EU of less than 45 %.

In 2013, Italy also showed the biggest within-country dispersion of employment rates, with a factor of 1.8. This means employment rates in the country’s worst performing regions were 1.8 times lower than in its best performing ones. Strong within-county dispersions of regional employment rates could also be found in Spain and France, with a factor of about 1.4. In contrast, Denmark, Ireland, Croatia, the Netherlands and Sweden were the most ‘equal’ countries, with almost no disparities in employment rates across their regions.

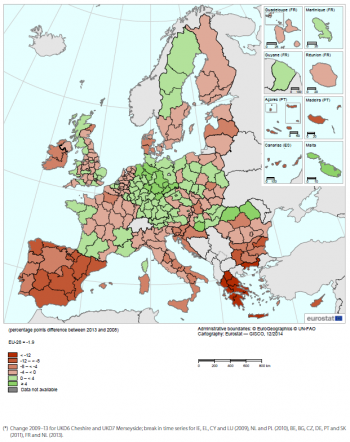

Map 2 shows the change in regional employment rates since 2008. Almost two-thirds (64.7 %) of the 272 NUTS 2 regions for which data are available have experienced a fall in their employment rates since the economic crisis began. Among the hardest hit, with reductions of 10 percentage points or more, were several regions in Greece and Spain as well as the Portuguese autonomous region of Madeira. Despite the economic crisis, employment rates increased in 93 regions over 2008 to 2013. Of these, 15 showed growth of more than 4 percentage points, 11 of which were in Germany (with the highest increases in Sachsen-Anhalt, Berlin, Leipzig and Chemnitz). The remaining four were in Hungary (Dél-Dunántúl), Romania (Nord-Est and Nord-Vest) and the UK (Highlands and Islands).

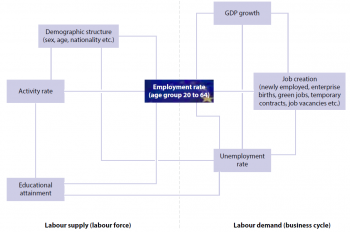

How long-term labour supply factors influence the employment rates

Employment rates are a result of labour supply and demand: workers supply labour to businesses and businesses demand labour from workers, both in exchange for wages. Consumers play an important role in businesses’ labour needs through their demand for products and services, which in turn is influenced by the cyclical development of the economy. Labour supply is characterised by the number of people available to the labour market (determined by demographic structure) and the skills they offer (approximated by education). However, the demographic structure of the economically active population and its education levels are two important factors that are hard to influence in the short term.

The EU’s labour force is shrinking because of an ageing population

The EU is confronted with a growing, but ageing population, which is driven by low fertility rates and a continuous rise in life expectancy. This ageing, already apparent in many Member States, means older people will make up a much greater share of the total population in the coming decades, while the share of the population aged 20 to 64 years will fall (see Figure 4). This in turn means that despite a growing population, the EU labour force is shrinking, increasing the burden on the employed population to provide for the social expenditure needed by an ageing population [3].

Over the past two decades the total EU population grew from 475 million in 1990 to 507 million in 2013 [4]. Between 2002 and 2013 the number of older persons aged 65 and above in-creased by 17.7 %. There was a particularly steep rise of 44.8 % for the group aged 80 or over. The population aged 20 to 64 years grew only slightly, by 3.6 % over the same period. In contrast, the number of 0 to 19 year olds fell by 5.8 %.

While the most recent projections [5] predict rapid growth in the number of older people, particularly in the group aged 80 years or over, the population aged 20 to 64 years is expected to start shrinking in the next few years as more baby boomers enter their 60s and retire. As a result, the share of 20 to 64 year olds is expected to gradually decline from 60.8 % in 2013 to 58.9 % in 2020. This equals a reduction of 6.5 million people. At the same time, the number of older people aged 65 or over will grow by about 12 million, reaching 20.4 % of the total population in 2020. As indicated in Figure 4, these trends will continue at an even faster rate in the following decade, with the population aged 20 to 64 shrinking to 55.9 % and those aged 65 or over climbing to 23.9 %, thus making up almost a quarter of the total population in 2030.

Figure 5 shows how the baby boomer generation has moved up the age pyramid since 2002. This generation is the result of high fertility rates in several European countries over a 20 to 30 year period to the mid-1960s. Baby boomers continue to comprise a significant part of the working population, however, the first of these large cohorts are now reaching retirement age. As a result of these demographic changes the old-age dependency ratio has increased from 26.3 % in 2002 to 29.9 % in 2013. This ratio shows the share of the population aged 65 and above compared with the population of 20 to 64 year olds. This means that while there were 3.8 people of working age for every dependent person over 65 in the EU in 2002, this number had fallen to 3.3 people by 2013. By 2020, the old-age dependency ratio is projected to reach 34.6 %, meaning there will be fewer than three people of working age for every dependent person over 65.

These trends underline the importance of making the most of the EU’s labour potential by raising the employment rate for men and women over the coming years. To meet labour market needs in a sustainable way, efforts are needed to help people stay in work for longer. Particular attention needs to be given to women, older workers and young people. With regard to young people, it is important to help them find work as soon as they leave education and ensure they remain employed.

Women as well as younger and older people are less economically active…

Not all people are economically active, as shown in Figure 16. This also concerns part of the population aged 20 to 64 years. Figure 6 shows the differences in activity rates between the sexes and across age groups. Activity rates in the EU are consistently higher for men than for women and are generally highest for people aged 30 to 49. The main reason why men and women around 20 years of age do not seek employment is because they are participating in education or training. In 2013, this was the case for about 90 % of the inactive population aged 15 to 24. On the other hand, people aged 50 or over slowly start dropping out of the labour market because of poor health or retirement. The low activity rates of 15 to 19 year olds due to education or training support the decision to raise the lower age limit for the strategy’s employment target from 15 to 20 years of age.

Parenthood is one of the main factors underlying the gender gap in activity rates. Because women are more often involved in childcare, parenthood is more likely to have an impact on their activity rates than on those for men, especially when care services are lacking or are too expensive. Indeed, the lower activity rates for women aged 25 to 49 years compared with men (see Figure 6) are a result of women staying at home for childcare (38.3 % in 2013) and other family or personal circumstances such as marriage, pregnancy or long vacation (15.5 % in 2013) [6]. In contrast, the main reasons why 25 to 49 year old men did not seek employment were illness or disability (36.4 % in 2013) and participation in education or training (20.5 % in 2013).

… and these groups therefore have lower employment rates

Figure 7 illustrates how the differences in activity rates (as shown in Figure 6) are mirrored in different employment rates for different age groups, and how these have changed over the past 10 years. Employment rates of people aged 30 to 54 are about 10 percentage points higher than the overall EU employment rate (referring to the population aged 20 to 64). Young people aged 20 to 29 have lower employment rates, and the gap between this group and those aged 30 to 54 years has widened since the crisis began (see Figure 7).

Employment rates of women and older people have risen more or less continuously over the past decade. Between 2002 and 2013, the employment rate of 55 to 64 year olds rose by 11.8 percentage points. Growth was even more pronounced for older women, at 14.3 percentage points. These increases are partly a result of the demographic changes in the EU: as baby boomers with high activity and employment rates move up the age pyramid, they eventually enter the 55 to 64 age group, pushing up the employment levels of older people.

This development is also apparent in the increase in the duration of working life. This is measured as the number of years a person aged 15 is expected to be active in the labour market. Over the past decade, the duration of working life in the EU has risen by 2.1 years, from 32.9 years in 2002 to 35.0 years in 2012. The increase was higher for women (+ 2.8 years) than for men (+ 1.4 years). However, in 2012 men could still expect to stay in work much longer (37.6 years) than women (32.2 years).

This reaffirms the focus Europe 2020 puts on 55 to 64 year old women to boost the overall employment rate: ‘A longer working life will both support the sustainability and the adequacy of pensions, as well as bring growth and general welfare gains for an economy. Higher employment rates among older people are also a precondition for the EU’s ability to reach the 2020 target, just as adequate pension systems are a precondition for the achievement of the poverty reduction target’ [7]. (see also the ‘Poverty and social exclusion’ article).

Lower activity rates of women due to parenthood (see Figure 6) also strongly influence the employability of women. The longer women are out of the labour market or are unemployed, notably due to care duties, the harder it will be for them to find a job in the long term. The gender employment gap, showing the difference in employment rates of men and women, is highest for 30 to 39 year olds and for the older cohort, as shown in Figure 8. However, the gap is slowly closing due to the stronger growth in employment rates of women over the past decade. European employment policies are addressing the specific situation of women to help raise their employment rates in line with the headline target.

Better educational attainment increases employability…

Educational attainment levels are another important factor for explaining the variation in employment rates between different groups in the labour force. Figure 9 shows employment rates are generally higher for more highly educated people.

In 2013, people who had completed tertiary education had a significantly higher employment rate than the EU average, at 81.7 %. In contrast, just slightly more than half (51.4 %) of those with at most primary or lower secondary education were employed. The rate for people with upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education was in between these levels, at 69.4 %, slightly above the EU average.

These findings underline the importance of people’s education for their employability. Increasing educational attainment and equipping people with skills for the knowledge society are therefore major concerns for European employment policies addressing the Europe 2020 headline targets on both employment and education (see ‘Education’ article).

…and reduces the risk of being unemployed, in particular for young people

As with employment, a clear link exists between unemployment and education: unemployment rates are generally lower for people with better education levels. In 2013, unemployment among those aged 15 to 74 with tertiary education was 6.4 %. This was significantly lower than the EU average of 10.8 %. In contrast, unemployment was considerably higher for those with at most lower secondary education, at 19.1 %.

Young people aged 15 to 29 generally face a higher risk of being unemployed. In 2013, their unemployment rate was 18.7 % and thus about eight percentage points above the EU average of 10.8 % (age group 15 to 74). This higher risk is particularly a problem for low-educated young people who have completed only lower secondary education (early leavers from education and training; see the ‘Education’ article). As shown in Figure 10, young people aged 15 to 29 with at most lower secondary education are clearly the most disadvantaged group, with an unemployment rate of almost 30 % in 2013. Unemployment rates for the other two groups were more than 12 percentage points lower.

At the same time, low-educated 15 to 29 year olds have experienced the biggest growth in unemployment since 2002, when their unemployment rate was about 11 percentage points lower. It is interesting to note that this decline compared with the other two subgroups has not only been caused by the recent economic crisis. The situation of low-educated 15 to 29 year olds had already started deteriorating gradually in the period before 2007 (see Figure 10), while unemployment in the other two, higher-educated groups had been falling until 2008.

In the context of the Europe 2020 strategy, it is important that young people maximise their professional working lives by engaging in employment as soon as possible and staying employed. This is specifically addressed through the flagship initiative ‘Youth on the Move’ (see 'Policies tackling youth unemployment' in the ‘Data sources and availability' section below).

Migration — a way to balance the ageing population

Economic migration is increasingly acquiring strategic importance for the EU in dealing with a shrinking labour force and expected skills shortages. Without net migration, the European Commission estimates the working-age population will shrink by 12 % in 2030 and by 33 % in 2060 compared with 2009 levels [8].

In 2013, non-EU citizens accounted for 3.9 % of the total EU population [9]. Their share in the labour force was even higher, at 4.4 %. However, migrant workers do not only often occupy low-skilled, low-quality jobs, they also show considerably lower employment rates than EU citizens (see Figure 11). In 2013, the employment rate of non-EU nationals aged 20 to 64 was 12.3 percentage points below the total employment rate and 12.8 percentage points below that of EU nationals. This is a significant widening of the gap since the onset of the economic crisis in 2008.

How short-term labour demand factors influence the employment rate

Employment (and unemployment) rates are closely linked to the business cycle. Usually this is expressed in terms of GDP growth, which can be seen as a measure of an economy’s dynamism and its capacity to create new jobs. This relationship is illustrated by Figure 12. It shows similar patterns for GDP growth, employment growth and the share of newly employed people in total employment (people who started their job within the past 12 months).

The situation observable in 2010 and 2011, with GDP growth picking up but employment recovery more or less stalled, can be described as ‘jobless growth’. This means GDP growth corresponded mostly to an increase in productivity and hours worked, leaving little room for employment growth [10]. As the result of another GDP contraction following the slight recovery in 2010 and 2011, the number of employed people fell again in 2012 and 2013.

The link between GDP growth and employment growth is also reflected in the share of newly employed people as a share of total employment, which dropped considerably in 2009, thus following the contractions in GDP and employment in the same year. It rose slightly in the following years, only to drop again to the lowest level of the decade in 2013.

How do enterprise births contribute to job creation?

The birth of new enterprises is often seen as one of the key drivers of job creation and economic growth. Enterprise births are thought to increase the competitiveness of a country’s enterprise population, by obliging them to become more efficient in view of newly emerging competition. As such, they stimulate innovation and facilitate the adoption of new technologies, while helping to increase an economy’s overall productivity.

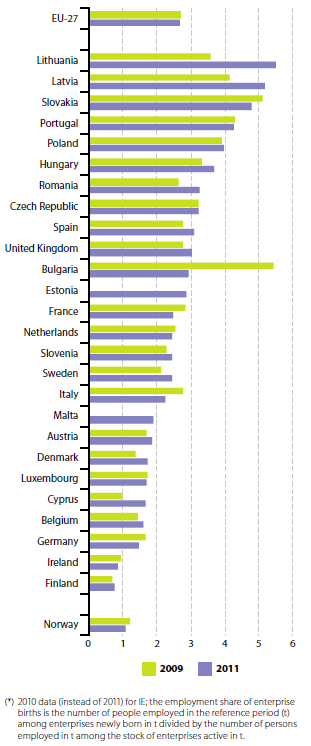

Figure 13 shows the share of newly born enterprises in total employment of active enterprises, in terms of number of persons employed in the business economy [11]. In 2011, employment shares ranged from more than 5 % in Lithuania and Latvia to slightly above 0.7 % in Finland. The EU average stood at 2.68 %, slightly lower than two years earlier.

The green economy as another key source of job creation?

The ‘Employment Package’ identified the green economy as a key source of job creation in Europe. According to European Commission estimates, the implementation of energy efficiency measures could create or retain two million jobs by 2020 and the development of renewable energy sources could lead to three million jobs by 2020 [12]. These so-called ‘green jobs’ cover ‘all jobs that depend on the environment or are created, substituted or redefined in the transition process towards a greener economy’ [13].

Available data on employment in the environmental goods and services sector (EGSS) encompass a set of sectors in the fields of environmental protection (for example waste management) and resource management (for example renewable energy, renewable raw materials and products). As Figure 14 shows, employment in the EU eco-industry is estimated to have risen more or less continuously over the past decade, reaching 4.2 million full-time equivalent positions in 2011. This represents about 2 % of total employment in the EU [14].

The economic crisis reversed positive employment trends

The overall favourable trend observable since the early 2000s in relation to employment and unemployment has been reversed by the economic crisis, with unemployment rates rising to above pre-crisis levels by 2013. The crisis had a bigger impact on employment in male-dominated sectors, such as construction and manufacturing. This led to men accounting for more than 80 % of the decline in employment between 2008 and 2010 in the EU [15].

Recessions tend to hit younger workers especially hard. Since the onset of the crisis in 2008, the employment rate of young people aged 20 to 29 has dropped by six percentage points, from 65.6 % in 2008 to 59.6 % in 2013. This reflects their generally weaker ‘attachment’ to the labour market. They are more likely to be in non-permanent contracts (see the analysis on ‘temporary contracts’ below) and are more vulnerable to ‘last-in, first-out’ redundancy policies [16]. In contrast, employment among older people aged 55 to 64, in particular women, has grown continuously from 38.4 % in 2002 to 50.2 % in 2013. Growth in this group has amounted to 4.6 percentage points since the onset of the crisis.

Looking at educational attainment, employment rates for all three sub groups have generally followed the overall EU trend before and after the crisis. People with the lowest education levels, however, were hardest hit, experiencing a 5.6 percentage points fall in their employment rate between 2007 and 2013 (see Figure 9). Similarly, migrants were especially affected by the crisis, being among the first to lose their jobs. Since 2008, the employment rate of non-EU nationals aged 20 to 64 has fallen by 6.7 percentage points. In comparison, employment of EU nationals of the same age had fallen by only 1.7 percentage points up to 2013 (see Figure 11).

Job seekers tend to become discouraged as an economic crisis drags on and some stop looking for work. These people drop out of the labour market and are thus no longer included in the unemployed population. However, they still represent an addition pool of the work force that could be available to the labour market if the economic situation improves. In the EU, the number of people ‘available to work but not seeking’ employment has risen by 25.7 % since the onset of the economic crisis, from 2.0 % of the population aged 15 to 74 [17] in 2008 to 2.4 % in 2013. This group includes mainly discouraged jobseekers and people prevented from seeking work by personal or family circumstances.

Temporary contracts as adjustment variable for companies during crises

Fluctuations in EU job numbers since the crisis began have been driven mainly by part-time work and temporary contracts. In particular, companies have used temporary contracts to adjust to changes in their labour needs. Employees having these types of contracts have made up the most reactive segment of the labour market since the crisis broke out [18].

The proportion of the EU labour force working on a fixed-term contract has risen steadily since 2001. Temporary employment in the EU was most widespread among young people, with 31.4 % of 15 to 29 year olds working on a time-limited contract in 2013. The rate of temporary employment was much lower for 20 to 64 year olds at 12.8 % and for older people aged 55 to 64 at 6.5 % in the same year.

However, some people prefer fixed-term contracts to permanent ones. Therefore, involuntary temporary employment provides a better insight into the overuse of fixed-term contracts. In 2013, 8.4 % of employed 20 to 64 year olds were involuntarily working on temporary contracts. The share was much higher for young people aged 15 to 29, at 14.8 %. Despite some fluctuations, the overall trend since 2001 indicates growing use of involuntary fixed-term contracts.

The rise in temporary contracts and other non-standard forms of employment, in particular for newly created jobs, signals increasing fluidity in the labour market. This is making it easier for firms to adapt labour input to new forms of production and work organization [19].

Job vacancies as an indicator of unmet labour demand

Job vacancy statistics provide an insight into the demand side of the labour market, in particular unmet labour demand. A job vacancy is defined as a paid post that is newly created, unoccupied or about to become vacant. The employer must be taking active steps and be prepared to take further steps to find a suitable candidate from outside the enterprise. The employer must also intend to fill the position either immediately or within a specific period of time. A vacant post that is only open to internal candidates is not treated as a ‘job vacancy’.

Quarterly job vacancy statistics are used for business cycle analysis and for assessing mismatches in labour markets. Of particular interest is the relationship between vacancies and unemployment — the so-called Beveridge curve (see Figure 15). The curve reflects the negative relationship between vacancies and unemployment. During economic contractions there are few vacancies and high unemployment while during expansions there are more vacancies and the unemployment rate is low.

Structural changes in the economy can cause the Beveridge curve to shift. During times of uneven growth across regions or industries — when labour supply and demand are not matched efficiently — the vacancy and unemployment rates can rise at the same time. Conversely, they can both decrease when the matching-efficiency of the labour market improves. This could be, for example, due to a better flow of job vacancy information thanks to the internet. Empirical analysis of the curve can be challenging because both movements along the curve and shifts can take place at the same time with different intensities.

Data for the period 2008 to 2009 show a movement along the Beveridge curve, mirroring the impacts of the economic crisis on job vacancies and unemployment. Since 2010, however, movements of the Beveridge curve itself point to a possibly substantial deterioration in the matching process: unemployment has been growing, while the job vacancy rate has remained stable or has also been increasing. This was the case in the fourth quarter of 2013 and the first quarter of 2014. This indicates unemployment has become more structural over the past years [20]. EU policies that address job vacancies aim to improve the functioning of the labour market by trying to match supply and demand more closely (see 'Data sources and availability' below).

Conclusions and outlook towards 2020

Between 2002 and 2008, the EU employment rate for the age group 20 to 64 rose by 3.6 percentage points, from 66.7 % in 2002 to 70.3 % in 2008. Growth was visible throughout different labour groups, such as men, women, older and younger people, high- and low-skilled people and migrants. Older people aged 55 to 64 years showed the strongest growth, starting from a low employment level of 38.1 % in 2002. Similarly, employment rates for women grew faster than for men, reducing the gender employment gap. Mirroring these trends, unemployment rates declined over 2000 to 2008, with 7.0 % of economically active 15 to 74 year olds unemployed in 2008. However, despite falling considerably by 2.6 percentage points between 2002 and 2008, the unemployment rate of young people aged 15 to 29 was still much higher at 12.0 % in 2008.

As a result of the EU economy shrinking by 4.5 % in 2009 due to the economic crisis, employment levels fell and unemployment in turn rose up to 2013. The fall in employment rates in recent years has most affected young people aged 15 to 29, people with low education levels and non-EU nationals. The unemployment rate of young people aged 15 to 29 increased to 18.7 % in 2013. Similarly, unemployment levels of low-skilled people have increased by 7.6 percentage points since 2007, reaching 19.1 % in 2013. Low-educated young people are clearly the worst off, with their unemployment rate climbing to 29.9 % in 2013, which is 10 percentage points higher than in 2007. Additionally, the economic crisis has prompted more and more people to drop out of the labour market, meaning they are no longer included in unemployment statistics. Since 2008, the number of people that would be available to work but are not seeking employment has risen by 25.7 %.

Temporary contracts are one reason why young people are more vulnerable to economic disruptions. Fluctuations in EU job numbers since the crisis have been mainly driven by part-time work and fixed-term contracts. In 2013, 31.4 % of 15 to 29 year olds worked on time-limited contracts, although almost half (47.2 %) wanted a permanent contract. Also, data on job vacancies point to a possible deterioration in the job matching process, with unemployment rising while job vacancies have remained stable and, recently, have started rising again.

The economic crisis thus highlighted some of the most vulnerable groups (young people, migrants, low-skilled) that need to be addressed in view of the Europe 2020 strategy’s ‘inclusive growth’ priority. In addition, women, especially those aged 55 to 64 years, and older people in general still have considerably lower employment rates than other groups. Boosting employment within these groups is considered necessary for making progress towards the overall EU and national employment targets [21].

Additionally, long-term changes in the demographic structure of the EU population add to the need to increase the EU’s employment rate. Despite a growing population, low fertility rates combined with continuous rises in life expectancy are predicted to lead to a shrinking EU labour force. Increases in the employment rate are therefore necessary to compensate for the expected decline in the working-age population by 3.5 million people by 2020.

Efforts needed to meet the Europe 2020 target on employment

Overall, in 2013 the EU was 6.6 percentage points below its target value of 75 %, to be met by 2020. Based on recent trends, the European Commission expects the EU employment rate to only reach about 72 % in 2020. Even if all countries were to meet their national Europe 2020 targets, the overall EU employment rate would only grow to 74 %, just below the 2020 target [22]. To reach the 75 % target an extra 16 million people would need to enter employment, taking into account the expected working-age population in 2020. While a large share of young and well-educated people will be available to work (also see the article on ‘Education’), achieving the EU target will require greater use of the potential labour force, including women, older people and so far inactive adults such as migrants [23].

Data sources and availability

What is meant by ‘labour force’, ‘activity’, ‘employment’ and ‘unemployment’?

The term ‘labour force’ refers to the economically active population. This is the total number of employed and unemployed persons. People are classified as employed, unemployed and economically inactive according to the definitions of the International Labour Organisation (ILO) [24]. On an EU level the two main sources for this data are the EU Labour Force Survey (EU LFS) [25] and National Accounts (including GDP) [26].

(%)

Source: Eurostat online data code: (Ifsa_pganws)

The EU LFS is a large sample survey of private households, excluding the population living in institutional households (such as workers’ homes or prisons). Respondents are classified as employed, unemployed or economically inactive based on information collected through the survey questionnaire, which mainly relates to their actual activity during a particular reference week. The EU LFS data refer to the resident population and therefore the results relate to the country of residence of persons in employment, rather than to the country of work. This difference may be significant in countries with large cross-border flows.

According to the definitions:

The economically active population, as already mentioned, is the sum of employed and unemployed persons. Inactive persons are those who, during the reference week, were neither employed nor unemployed.

- The activity rate is the share of the population that is economically active.

- Economic activity is measured only for persons aged 15 years or older, because this is the earliest that a person can leave full-time compulsory education in the EU [27]. Many Member States have also made 15 the minimum employment age [28].

Persons in employment are those who, during the reference week, did any work for pay or profit, or were not working but had a job from which they were temporarily absent. ‘Work’ means any work for pay or profit during the reference week, even for as little as one hour. Pay includes cash payments or payment in kind (payment in goods or services rather than money), whether payment was received in the week the work was done or not. Anyone who receives a wage for on-the-job training that involves the production of goods or services is considered as being in employment. Self-employed and family workers are also included.

- Employment rates represent employed persons, as a percentage of the same age population; they are frequently broken down by sex and different age groups.

- For the employment rates, data most often refer to persons aged 15 to 64. But in the course of setting the Europe 2020 strategy’s employment target, the lower age limit has been raised to 20 years. One reason was to ensure compatibility with the strategy’s headline targets on education (see the article on ‘Education’), in particular the one for tertiary education [29]. The upper age limit for the employment rate is usually set to 64 years, taking into account statutory retirement ages across Europe [30]. However, the possibility of raising the upper age limit for the employment rate is being considered [31].

Unemployed persons comprise persons aged 15 to 74 who were:

- without work during the reference week, i.e. neither had a job nor were at work (for one hour or more) in paid employment or self-employment;

- available to start work, i.e. were available for paid employment or self-employment before the end of the two weeks following the reference week;

- actively seeking work, i.e. had taken specific steps in the four-week period ending with the reference week to seek paid employment or self-employment or who found a job to start within a period of at most three months.

- The unemployment rate is the number of unemployed persons as a percentage of the labour force (the total number of people employed and unemployed);

- The youth unemployment rate is the unemployment rate of people aged 15 to 24; for the purpose of this article the analysis is extended to the age group 15 to 29, which is the age group addressed by the EU Youth Strategy;

- The long-term unemployment rate is the number of persons unemployed for 12 months or longer as a percentage of the labour force.

- To take into account persons that would like to (or have to) work after the age of 64 but are un-able to find a job, the upper age limit for the unemployment rate is usually set to 74 years of age. As a result, the observed age group for unemployed persons is 15 to 74 years.

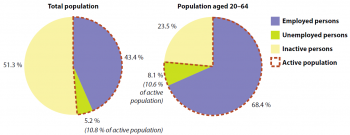

Figure 16 shows the distribution of employed, unemployed and inactive persons for the total population [32] and for the population aged 20 to 64 years. The latter shows the working-age population addressed by the Europe 2020 strategy’s employment target.

In 2013, less than half of the total LFS population of 500 million people [33] was economically active. The 257 million inactive people include children and retired people. For labour market analyses, the focus is therefore on people aged 20 to 64. In 2013, more than three-quarters of people aged 20 to 64 were economically active; 209 million (68.4 % of the population aged 20 to 64) were employed and 25 million were unemployed (8.1 % of the same age group, equalling a 10.6 % share of the economically active population aged 20 to 64 years); 72 million people aged 20 to 64 were economically inactive.

Based on these data, the following indicators are usually calculated to analyse labour market trends:

- Activity rate: in 2013, 48.7 % of the total population or 76.5 % of the population aged 20 to 64 years were active on the labour market.

- Employment rate: in 2013, 43.4 % of the total population or 68.4 % of the population aged 20 to 64 years were employed.

- Unemployment rate: in 2013, 10.8 % of the active population (referring to the age group 15 to 74) or 10.6 % of economically active 20 to 64 year olds were unemployed.

Employment policies specifically targeting women

One of the priorities of the flagship initiative ‘An Agenda for new skills and jobs’ is to create new momentum for flexicurity policies aimed at modernising labour markets and promoting work through new forms of flexibility and security. Under the flexibility component, ‘Flexible and reliable contractual arrangements’, the flagship initiative calls for ‘putting greater weight on internal flexibility in times of economic downturn’: ‘Flexibility also allows men and women to combine work and care commitments, enhancing in particular the contribution of women to the formal economy and to growth, through paid work outside the home.’ [34]

The security component is addressed by the EU employment package ‘Towards a job-rich recovery’ under its objective of restoring the dynamics of labour markets. This calls for ‘security in employment transitions’, such as the transition from maternity leave to employment: ‘the integration of women in the labour market [deserves particular attention], by providing equal pay, adequate childcare, eliminating all discrimination and tax-benefit disincentives that discourage female participation, and optimising the duration of maternity and parental leave.’ [35]

Employment policies addressing migration

‘In the longer term, and especially in view of the EU’s demographic development, economic immigration by third-country nationals is a key consideration for the EU labour market’ [36]. The EU employment package ‘Towards a job-rich recovery’ specifically addresses the relevance of migration for tackling expected skills shortages: ‘With labour needs in the most dynamic economic sectors set to rise significantly between now and 2020, while those in low-skills activities are set to decline further, there is a strong likelihood of deficits occurring in qualified job-specific skills’.

Employment policies and education

'Improving the matching process between labour supply and demand by adapting educational and training systems to produce the skills required on the labour market is a key priority of the Europe 2020 strategy’s flagship initiative ‘An Agenda for new skills and jobs’. It proposes a bundle of measures aimed at strengthening the EU’s capacity to anticipate and match labour market and skill needs. These include labour market observatories bringing together labour market actors and education and training providers, measures enhancing geographical mobility throughout the EU, and actions towards better integration of migrants and better recognition of their skills and qualifications [37].

Investing in skills is also a priority of the EU employment package ‘Towards a job-rich recovery’. Under its objective of restoring the dynamics of labour markets, the European Commission calls for a better monitoring of skills needs and ‘a close cooperation between the worlds of education and work’.

It also addresses youth employment, calling for ‘security in employment transitions’, such as the transition of young people from education to work. It also reaffirms the EU’s commitment to tackle the dramatic levels of youth unemployment, ‘by mobilising available EU funding’ and by supporting the transition to work ‘through youth guarantees, activation measures targeting young people, the quality of traineeships, and youth mobility’ [38].

Policies tackling youth unemployment

The Europe 2020 flagship initiative ‘Youth on the Move’ emphasises that ‘youth unemployment is unacceptably high’ in the EU, and that ‘to reach the 75 % employment target for the population aged 20 to 64 years, the transition of young people to the labour market needs to be radically improved’. To this end, the flagship initiative focuses on four main lines of action [39]:

- Lifelong learning, to develop key competences and quality learning outcomes, in line with labour market needs. This also means tackling the high level of early school leaving.

- Raise the percentage of young people participating in higher education or equivalent to keep up with competitors in the knowledge-based economy and to foster innovation.

- Improve learning mobility programmes and initiatives, to support the aspiration that by 2020 all young people in Europe should have the possibility of spending a part of their education abroad, including via workplace-based training.

- Urgently improve the employment situation of young people, by presenting a framework of policy priorities for action at national and EU level to reduce youth unemployment by facilitating the transition from school to work and reducing labour market segmentation.

Context

Employment — why does it matter?

Employment and other labour market-related issues are at the heart of the social and political debate in the EU. Paid employment is crucial for ensuring sufficient living standards and it provides the necessary base for people to achieve their personal goals and aspirations. Moreover, employment contributes to economic performance, quality of life and social inclusion, making it one of the cornerstones of socioeconomic development and well-being.

The EU’s workforce is shrinking as a result of demographic changes. A smaller number of workers are thus supporting a growing number of dependent people. This is putting at risk the sustainability of Europe’s social model, welfare systems, economic growth and public finances. In addition, steady gains in economic growth and job creation over the past decade have been wiped out by the recent economic crisis, exposing structural weaknesses in the EU’s economy. At the same time, global challenges are intensifying and competition from developed and emerging economies such as China or India is increasing [40].

To face the challenges of an ageing population and rising global competition, the EU needs to make full use of its labour potential. The Europe 2020 strategy, through its ‘inclusive growth’ priority, has placed a strong emphasis on job creation. One of its five headline targets addresses employment, with the aim of raising the employment rate of 20 to 64 year olds to 75 % by 2020. This goal is supported by the so-called ‘Employment Package’ [41], which seeks to create more and better jobs throughout the EU.

The article analyses the headline indicator ‘Employment rate — age group 20 to 64’, chosen to monitor the employment target. Contextual indicators are used to present a broader picture, looking into the drivers behind the changes in the headline indicator. These include indicators from both the supply and demand side of the labour market, as shown in Figure 2.

Concerning labour supply, the analysis investigates the structure of the EU’s labour force and its long-term influence on employment in relation to the strategy’s main target groups: migrants, women and young, older and low-skilled people. These groups are important because of their low employment rates; reaching the Europe 2020 target consequently means tapping into the potential labour force that they represent [42].

The analysis then shifts to short-term, demand-oriented factors related to the cyclical development of the economy (as expressed through GDP growth) such as job vacancies, and how this influences job creation, temporary employment and unemployment.

The EU’s employment target is closely interlinked with the other strategy goals on research and development (R&D) (see the article on 'R&D and innovation'), climate change and energy (see the article on 'Climate change and energy'), education (see the article on 'Education') and poverty and social exclusion (see the article on 'Poverty and social exclusion'). Progress towards one target therefore also depends on how the other targets are addressed. Better educational levels help employability and higher employment rates in turn help reduce poverty. Moreover, greater R & D capacity, together with increased resource efficiency, will improve competitiveness and contribute to job creation. The same is true for investing in energy efficiency measures and boosting renewable energies [43].

See also

Further Eurostat information

Publications

Main tables

Dedicated section

Methodology / Metadata

- Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council COM(2011) 211 final Towards robust quality management for European Statistics

Other information

- Regulation 223/2009 of 11 March 2009 on European statistics

External links

Notes

- ↑ European Commission, Taking stock of the Europe 2020 strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, COM(2014) 130 final, Brussels, 2014.

- ↑ See http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/europe_2020_indicators/documents/Europe_2020_Targets.pdf..

- ↑ European Commission (Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion & Eurostat), Demography Report 2010 — Older, more numerous and diverse Europeans, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2011 (p. 59)

- ↑ Please note that the total population figures presented here differ from the population concept used in the EU LFS, which only covers resident persons living in private households, excluding the population living in institutional households (such as workers’ homes or prisons). The data are based on Eurostat data tables (demo_pjan) and (proj_13npms)

- ↑ EUROPOP2013 main scenario; see. http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/cache/ITY_SDDS/en/proj_13n_esms.htm.

- ↑ Eurostat, EU Labour Force Survey — explanatory notes, Luxembourg, 2011 (p. 80)

- ↑ European Commission (Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion), Employment and Social Developments in Europe 2012, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2012 (p. 57)

- ↑ European Commission, An Agenda for new skills and jobs: A European contribution towards full employment, COM(2010) 682 final, Strasbourg, 2010 (p. 9)

- ↑ The target population of the EU LFS are resident persons living in private households, excluding the population living in institutional households (such as workers’ homes or prisons)

- ↑ European Commission (Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion), Employment and Social Developments in Europe 2012, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2012 (p. 19).

- ↑ NACE Rev. 2 code B-N_X_K642: Business economy except activities of holding companies.

- ↑ European Commission, Towards a job-rich recovery, COM(2012) 173 final, Strasbourg, 2012 (p. 5).

- ↑ European Commission, Green jobs: employment potential and challenges (accessed 11 July 2014).

- ↑ European Commission, Green jobs: employment potential and challenges (accessed 11 July 2014).

- ↑ European Commission (Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion), Employment and Social Developments in Europe 2011, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2012 (p. 47).

- ↑ European Commission (Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion), Employment and Social Developments in Europe 2011, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2012 (p. 48).

- ↑ The target population of the EU LFS are resident persons living in private households, excluding the population living in institutional households (such as workers’ homes or prisons).

- ↑ European Commission [Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion), Employment and Social Developments in Europe 2012, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2012 (p. 31).

- ↑ European Commission, Towards a job-rich recovery, COM(2012) 173 final, Strasbourg, 2012 (p. 10).

- ↑ European Commission (Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion), Employment and Social Developments in Europe 2012, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2012 (p. 29).

- ↑ European Commission, Taking stock of the Europe 2020 strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, COM(2014) 130 final, Brussels, 2014 (p. 12).

- ↑ European Commission, Taking stock of the Europe 2020 strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, COM(2014) 130 final, Brussels, 2014 (p. 12).

- ↑ European Commission, Taking stock of the Europe 2020 strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, COM(2014) 130 final, Brussels, 2014 (p. 12).

- ↑ For more information see the ILO website: http://www.ilo.org/global/lang--en/index.htm.

- ↑ For more information on the EU LFS, see: http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/employment_unemployment_lfs/introduction.

- ↑ For more information see: http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/national_accounts/introduction.

- ↑ João Medeiros & Paul Minty, Analytical support in the setting of EU employment rate targets for 2020, Working Paper 1/2012, Brussels: European Commission (Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs & Inclusion), 2012 (p. 58).

- ↑ European Commission (Directorate-General for Justice), Age and Employment, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2011 (p. 50).

- ↑ João Medeiros & Paul Minty, Analytical support in the setting of EU employment rate targets for 2020, Working Paper 1/2012, Brussels: European Commission (Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs & Inclusion), 2012 (p. 12).

- ↑ European Commission (Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs), The 2012 Ageing Report: Economic and budgetary projections for the EU27 Member States (2010–2060), 2012 (p. 99).

- ↑ João Medeiros & Paul Minty, Analytical support in the setting of EU employment rate targets for 2020, Working Paper 1/2012, Brussels: European Commission (Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs & Inclusion), 2012 (p. 15).

- ↑ The target population of the EU LFS are resident persons living in private households, excluding the population living in institutional households (such as workers’ homes or prisons).

- ↑ The target population of the EU LFS are resident persons living in private households, excluding the population living in institutional households (such as workers’ homes or prisons).

- ↑ European Commission, An agenda for new skills and jobs: A European contribution towards full employment, COM(2010) 682 final, Strasbourg, 2010 (p. 5).

- ↑ European Commission, Towards a job-rich recovery, COM(2012) 173 final, Strasbourg, 2012 (p. 10).

- ↑ European Commission, Towards a job-rich recovery, COM(2012) 173 final, Strasbourg, 2012 (p. 18).

- ↑ European Commission, Towards a job-rich recovery, COM(2012) 173 final, Strasbourg, 2012 (p. 18).

- ↑ European Commission, Towards a job-rich recovery, COM(2012) 173 final, Strasbourg, 2012 (p. 10).

- ↑ European Commission, Youth on the Move: An initiative to unleash the potential of young people to achieve smart, sustainable and inclusive growth in the European Union, COM(2010) 477 final, Brussels, 2010 (p. 3f).

- ↑ European Commission, Europe 2020 — A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, COM(2010) 2020 final, Brussels, 2010 (p. 5, 7, 17), European Commission, An Agenda for new skills and jobs: A European contribution towards full employment, COM(2010) 682 final, Strasbourg, 2010 (p. 2).

- ↑ European Commission, Towards a job-rich recovery, COM(2012) 173 final, Strasbourg, 2012.

- ↑ European Commission, Taking stock of the Europe 2020 strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, COM(2014) 130 final, Brussels, 2014 (p.12).

- ↑ European Commission, Europe 2020 — A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, COM(2010) 2020 final, Brussels, 2010 (p. 11).