Archive:Youth in Europe

- Data from July 2009: [Further Eurostat information, Main tables and Database]]]].

Introduction

In 2007, the European Union counted around 96 million

young people aged between 15 and 29 years. These young people and their elders are facing two demographic challenges: the ageing and the impending decline of the European population. In fact, according to projections, by 2050 the population aged under 15 will account for a quarter of all persons of working age (15–64) and for half of the population aged over 64. Overall, young people represented just under a fifth of the EU population in 2007. At national level, the most ‘youthful’ nations in the EU included Ireland, Cyprus, Slovakia and Poland, which counted the highest proportion of young people in the total population (more than 24 %). By contrast, in Denmark, Germany and Italy young people accounted for less than 18 % of the population. International migration has become an important driver of European population growth. However, the available data to monitor this phenomenon are still difficult to analyse since no criterion (e.g. citizenship or residence) perfectly captures international mobility. Among the EU Member States for which data are available, Spain, Austria and Germany recorded the highest shares of foreigners among the young population aged 15–29 (representing respectively 15 %, 14 % and 12 %). Leaving the parental nest, getting married and having children: there’s no hurry The path from childhood to independent adulthood is lined with a number of crucial milestones and decisions, such as leaving the parental home to study or to work, moving in with a partner, getting married and having children. However, this road is not a one-way street; difficulties in securing a steady job or sufficient income and the dissolution of the couple or family may force young people to return to the parental home. In 2007, young women generally tended to leave the parental home earlier (by one or two years) than young men but strong disparities were noted across countries. Indeed, women tended to leave the parental nest at the average age of 22 in Finland, and 29 in Italy, Malta, Slovenia and Slovakia. For young men, the average age ranged from 23 to over 30. Material reasons were often put forward when young Europeans were asked via opinion polls why they or their peers tended to delay leaving the parental home. In fact, 44 % of young Europeans (aged 15–30) consider that young adults cannot afford to leave the parental home and 28 % agree that not enough affordable housing is available. However, in some countries, more than 20 % of young respondents consider that remaining with their parents allows them to live more comfortably with fewer responsibilities. In 2006, first marriages usually involved women younger than 30 in a majority of countries. As concerned men, in nearly half of the countries, a majority of first marriages concerned men older than 30. For women, getting married below 20 years of age is a relatively rare phenomenon in European countries, except for Romania and Turkey. Despite a recent upturn in the average number of children per woman in several Member States, the highest national fertility rates noted in the EU are still beneath the replacement level. The average age at which women have their first child ranged from 25 to 30 and has increased in all Member States over the 1995–2005 period. In a majority of countries, more than half of first births took place after the age of 25 when considering first-time mothers aged 15–29. In Germany, Spain and the United Kingdom, first-time mothers over 30 were even more numerous than their younger counterparts. Living on a shoestring? In 2007, 20 % of young Europeans aged 18–24 were at risk of poverty — i.e. living in households who had at their disposal less than 60 % of the median equivalised income of the country they live in. Moreover, the average income of young people aged 16–24 was much lower than that of their elders aged 25–49, as young people still in education either have not started working or are at the beginning of their career. In 2007, less than 10 % of young European households (the oldest member of which is aged under 30) were unable to afford a meal with meat or fish every second day and to buy a

FOUNDING A FAMILY: YOUNG WOMEN LEAVE THE PARENTAL HOME EARLIER THAN

MEN

Leaving the security of the parental nest to live independently

is usually a challenging experience for young people. There

are many factors involved in the decision to leave the parental

home, including the ‘quality’ of the home environment (in

terms of the parent-child relationship and living conditions),

having a strong relationship with a partner, studying full-time

or not, support from parents in cash or in kind, labour market

conditions, the cost of housing, etc. Moreover, such a decision

may not be definitive: difficulties in securing a full-time

permanent job or sufficient income and the possible

dissolution of the couple or family may force young people to

return to the parental home.

In 2007, in all countries for which data are available, women

moved out of the parental home on average at an earlier age

than men, but strong disparities were noted across countries

(see Figure 2.1). Indeed, in Finland women tended to leave

the parental home at the age of 22, against over 29 in Italy,

Malta, Slovenia and Slovakia. For men, the average age of

independence varied from 23 years in Finland to over 30 years

in Bulgaria, Greece, Italy, Malta, Romania, Slovenia and

Slovakia.

Main statistical findings

Just under 20 % of the population in the EU-27 is aged between 15 and 29. However, low fertility rates and longer life expectancy suggest that this figure is set to fall in the next decades. This indicates that society is reshaping and that younger generations will have to face the subsequent economic and social changes. Migration must also be taken into account when talking about the age composition of the population. Europe is an attractive place for people coming from outside Europe and a large proportion of migrants are young people. Mobility within the EU also contributes to the changing structure of society. Europe is facing new challenges, and its youngest generations will have to overcome them, just as the previous generations had to face the challenges of their time. Demography 1 YOU ARE YOUNG ONLY ONCE… BUT WHEN DO YOU STOP BEING ‘YOUNG’? There is no clear-cut definition of youth since it may be considered as a transition phase. Youth can be defined as ‘the passage from a dependant childhood to independent adulthood’ when young people are in transition between a world of rather secure development to a world of choice and risk. (1) Finding a common definition of youth is not an easy task. Age is a useful but insufficient indication to characterise the transition to adulthood. Some qualitative information reveals how societies acknowledge the increasing maturity of young people (see Table 1.1). Table 1.1: Some determinants of adulthood Source: MISSOC, Eurydice, EKCYP Note: age limit of child benefit: the age in bracket refers to the maximum age until child benefit may be prolonged. Such a prolongation depends on different conditions across countries. Voting age: DE: depends on the type of election in some Länder; IT: depends on the type of election; SI: varies according to additional conditions.

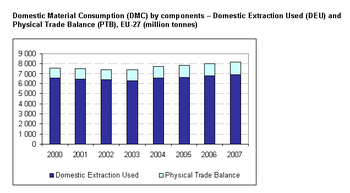

<description and/or analysis of most important statistical data, illustrated by tables and/or graphs>

Text with Footnote [1]

MULTINATIONAL YOUTH

Europe has experienced major changes in international migration patterns since the end of the Second World War, most notably through a progressive shift from emigration to immigration. This trend has gained strength and international immigration has become a key factor in the population growth of the European Union. Immigration, involving mostly young people has a rejuvenating impact on the age composition of the population. On the other hand, population ageing, including the ageing of the workforce as well as the imminent population and labour force decline, will continue to function as a major pull factor for international immigration. However, migration flows remain hard to predict as international migration remains a volatile demographic process. Furthermore, besides established immigration flows from outside of the European Union, migration flows between Member States have become increasingly important. The number of foreign citizens resident in a country — either citizens of other EU Member States or of non-EU countries — can serve as an indicator of the scale and patterns of migration. However, some caution is required in interpreting these figures. It should be noted that having a citizenship different from that of the country of residence is not necessarily the direct result of immigration. Many resident foreign citizens have not immigrated themselves but are descendants of migrants, born in the country of residence and having kept the citizenship of their parents. Conversely, some migrants may acquire the citizenship of the destination country and are no longer counted as foreign citizens. The number of foreign citizens also depends on national legislation regarding immigration and the acquisition of citizenship. Thus, the current size and composition of the foreign population is the result of both recent and historical immigration. Immigration is influenced by various factors such as linguistic or former colonial ties (for example, immigration to Spain, the United Kingdom, France and the Netherlands), favourable economic conditions, or a combination of these factors. Unfortunately, population statistics by citizenship and age group are not available for all countries. The data presented below refer to less than half of the EU Member States. The largest group of third-country citizens living in the European Union are from Turkey and Morocco. Citizens of Turkey comprise the largest group of foreigners in Germany, Denmark and the Netherlands, while Moroccans are the most numerous in Belgium, France and Spain. Figure 1.3 indicates that more than 15 % of young people in Spain in 2007 were foreign citizens. This was the highest share among the 14 EU Member States for which data are available. Austria and Germany ranked second and third, with 14 % and 12 % respectively. In these three countries, more than two thirds of foreigners were citizens of a non-EU country. The lowest shares of foreign citizens can be found in Poland, Romania and Slovakia, as well as in some of the other countries that joined the EU in the last few years. Among the 16 countries for which data are available (14 EU Member States and two EFTA countries), Switzerland recorded the highest share of foreigners among the population aged 15–29 (23 %), of which nearly half (48 %) were citizens of an EU Member State.

FOUNDING A FAMILY: YOUNG WOMEN LEAVE THE PARENTAL HOME EARLIER THAN

MEN

Leaving the security of the parental nest to live independently is usually a challenging experience for young people. There are many factors involved in the decision to leave the parental home, including the ‘quality’ of the home environment (in terms of the parent-child relationship and living conditions), having a strong relationship with a partner, studying full-time or not, support from parents in cash or in kind, labour market conditions, the cost of housing, etc. Moreover, such a decision may not be definitive: difficulties in securing a full-time permanent job or sufficient income and the possible dissolution of the couple or family may force young people to return to the parental home. In 2007, in all countries for which data are available, women moved out of the parental home on average at an earlier age than men, but strong disparities were noted across countries (see Figure 2.1). Indeed, in Finland women tended to leave the parental home at the age of 22, against over 29 in Italy, Malta, Slovenia and Slovakia. For men, the average age of independence varied from 23 years in Finland to over 30 years in Bulgaria, Greece, Italy, Malta, Romania, Slovenia and Slovakia.

Data sources and availability

<description of data sources, survey and data availability (completeness, recency) and limitations>

Context

<context of data collection and statistical results: policy background, uses of data, …>

Further Eurostat information

Publications

Main tables

- Title(s) of second level folder (if any)

- Title(s) of third level folder (if any)

Database

- Title(s) of second level folder (if any)

- Title(s) of third level folder (if any)

Dedicated section

Other information

<Regulations and other legal texts, communications from the Commission, administrative notes, Policy documents, …>

- Regulation 1737/2005 of DD Month YYYY on ...

- Council Directive 86/2003 of DD Month YYYY

- Commission Decision 86/2003 of DD Month YYYY

<For other documents such as Commission Proposals or Reports, see EUR-Lex search by natural number>

<For linking to database table, otherwise remove: {{{title}}} ({{{code}}})>

External links

See also

Notes

- ↑ Text of the footnote.

[[Category:<Category name(s)>]] [[Category:<Statistical article>]]