Archive:Business economy - expenditure, productivity and profitability

- Data from January 2009, most recent data: Further Eurostat information, Main tables and Database

This article belongs to a set of statistical articles which analyse the structure, development and characteristics of the various economic activities in the European Union (EU). The present article is part of the business economy overview, and covers three aspects of the business economy:

- expenditure;

- productivity;

- profitability.

Main statistical findings

Operating expenditure

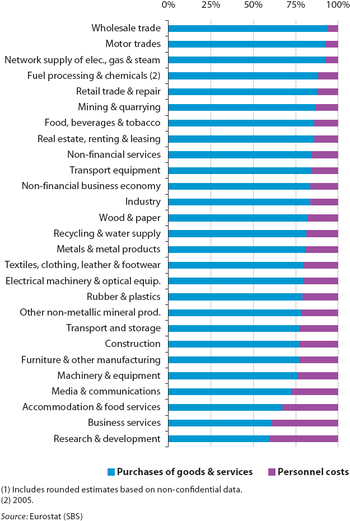

There are two components to operating expenditure which can provide an insight into the capital/labour intensities of different sectors and the extent to which they convert or distribute products. Figure 1 shows the expenditure structures of different activities, with a breakdown of operating expenditure into purchases of goods and services and personnel costs.

On average, some 83.9 % of EU-27 operating expenditure in the non-financial business economy was allocated to purchases of goods and services in 2006; the remaining 16.1 % was accounted for by personnel costs. Breakdowns for industry and non-financial services were both situated very close to these averages for the whole of the non-financial business economy, as 83.6 % of total operating expenditure within the industrial economy was devoted to purchases of goods and services, while the corresponding figure for non-financial services was 84.9 %. Construction was more labour-intensive, as 77.2 % of its total operating expenditure was accounted for by purchases of goods and services.

There were, however, considerable differences as regards the structure of operating expenditure between the aggregates used for the structural business statistics article headings. The three distribution activities of wholesale, motor and retail trade each reported that the proportion of operating expenditure allocated to purchases of goods and services was relatively high (upwards of 92 % for both wholesale and motor trades), no surprise, given that these activities are characterised by purchases for resale without transformation.

In contrast, all of the remaining non-financial services aggregates – with the exception of real estate, renting and leasing – were relatively labour-intensive, with personnel costs accounting for a higher than average proportion of total operating expenditure (when compared with the non-financial business economy average). There were two activities that stood out as being particularly labour-intensive, namely, business services and research and development, where personnel costs accounted for around 40 % of total operating expenditure. In the latter case, the relatively high share of personnel costs may, at least in part, be explained by the high costs associated with employing personnel with enough qualifications to carry out research and development.

Equally, the relative importance of personnel costs in total operating expenditure may, to some degree, reflect the average wages paid within each country. Many of the EU-27 Member States reported personnel costs accounting for a relatively high share of their total operating expenditure in 2006, with the highest proportion (19.0 %) recorded in France, while shares of 17 % or more were also recorded in the United Kingdom, Sweden, Germany, Austria and Denmark (see Table 1). This ratio was generally lower in the southern Member States where average personnel costs per employee were usually at lower levels. However, it was Cyprus that registered the highest proportion of total operating expenditure being devoted to personnel costs (22.0 % in 2005), largely reflecting the importance of the labour-intensive accommodation and food services sector in this popular tourist destination. Slovenia (15.5 % of operating expenditure accounted for by personnel costs) reported a cost structure that was similar to the EU-27 average (16.1 %), while the relative importance of personnel costs was considerably lower than average for the remaining Member States that joined the EU in 2004 or 2007 (no data for Malta).

Energy and raw material costs

For some activities a considerable proportion of purchases of goods and services are accounted for by energy and raw material costs, the EU displays a high degree of import dependency for many of these products.

The prices of energy and mineral products have fluctuated considerably in recent years – often as a reaction to market imbalances linked to increased demand from emerging economies (such as China, India or Brazil). Despite recent price reductions for products like petroleum, many raw material prices are still very high from a historical perspective. Relatively high oil prices are often used to explain fluctuations in gas prices, as the price of gas is often set in long-term contracts that are linked to the price of oil. Oil price increases are also generally passed down the production chain in the form of higher electricity prices, thus affecting a wide range of downstream activities, in particular, activities which are energy-intensive (such as the manufacture of iron and steel, aluminium, concrete or ceramics), or those industries that use oil and its derivatives as inputs in their own manufacturing processes (for example, the manufacture of chemicals, synthetic rubber and plastics).

The uncertainty faced by European businesses with respect to price developments of key, raw materials has been further magnified by concerns relating to the security of supply. Reliable deliveries of key, raw materials (including energy) are considered to be essential for the competitiveness of the European economy, as many products cannot be sourced from indigenous supplies (they either do not exist or they exist in such small volumes that it is not economically viable to mine/extract them).

The distribution of some of these essential raw materials is often concentrated in a limited number of countries: for example, China produces 95 % of all rare earth concentrates (needed for the manufacture of LCD’s), Brazil has 90 % of all niobium (needed for steel alloys in pipelines) and South Africa produces 79 % of all rhodium (used in car catalysts).

In November 2008, the European Commission proposed a new strategy – the Raw Materials Initiative (COM (2008) 699), which recommends that the EU defines a raw materials strategy based on three main pillars:

- access to raw materials on world markets at undistorted conditions;

- a framework to foster sustainable supply of raw materials from EU sources, and;

- the promotion of resource efficiency and recycling in the EU.

Figure 2 provides an insight into the main energy products that are purchased by EU-27 manufacturers. By far the most important energy product (in terms of its share of total energy expenditure) was electricity, accounting for 47.0 % of the total in the EU [1] in 2005, while natural and derived gas accounted for a further quarter (24.4 %).

A breakdown of purchases of energy products by selected industrial activities gives an indication of the importance of these energy products with respect to total purchases of goods and services. The data shown are presented for averages that are constructed on the basis of available data for the EU [2]in 2006. Figure 3 confirms that the most energy-intensive activities included non-energy mining and quarrying and the manufacture of other non-metallic mineral products, where energy costs accounted for around 10 % of all expenditure on goods and services. These ratios were more than double those recorded in the next most energy-intensive activities, namely, the production of pulp and paper, and the manufacture of basic metals.

Personnel costs

European personnel costs are generally quite high in relation to most other regions of the world. As some enterprises have switched their output to lower labour cost regions, those that remain based in Europe have tended to specialise in high value products, proximity services, niche markets, as well as integrated products and services. Some of these strategies often require a more educated workforce, which is more likely to raise the efficiency of labour, for example, through promoting the integration of new ideas and technologies, thus raising productivity. As such, many European governments have, in recent years, focused on investing in skills, training and education, with the hope that this investment in human capital can fill job vacancies in key areas of the economy.

Personnel costs are defined as the total remuneration, in cash or in kind, payable by an employer to an employee (permanent and temporary employees as well as home workers) in return for work done by the latter, including taxes and employees' social security contributions that are retained by the unit, and employer's compulsory and voluntary social contributions. Note that there may be costs associated with employing staff that are not covered by personnel costs, for example, training, recruitment costs, or the provision of working clothes.

Personnel costs accounted for 16.1 % of the total operating expenditure of the EU-27's non-financial business economy in 2006. Average personnel costs per employee were EUR 28.8 thousand in the EU-27's non-financial business economy, rising somewhat higher for industrial activities (EUR 33.6 thousand per employee) than for construction (EUR 27.9 thousand) or non-financial services (EUR 26.4 thousand).

Across the aggregates that are used to define the structural business statistics sectoral articles, average personnel costs per employee were relatively high for: fuel processing and chemicals manufacturing (2005); research and development activities; the network supply of electricity, gas and steam; and transport equipment manufacturing. They rose to over EUR 46.0 thousand per employee for each of these activities, peaking at EUR 54.1 thousand per employee for fuel processing and chemicals manufacturing (see Figure 4).

For most of the other activities, EU-27 average personnel costs remained within the range of +/-EUR 10 thousand of the non-financial business economy average. Below this threshold there were accommodation and food services as well as retail trade and repair (two activities that reported the highest proportions of part-time employment), as well as textiles, clothing, leather and footwear manufacturing. It is important to note that the ratio of average personnel costs per employee is calculated on the basis of headcounts for employees (as opposed to full-time equivalents), which is particularly important with respect to some services, where the propensity to employ persons on a part-time basis is often quite high (see Business economy - employment characteristics for more details).

Figure 5 provides a breakdown of personnel costs. Wages and salaries represented 78.0 % of total personnel costs in the EU-27's non-financial business economy in 2006, leaving the remaining 22.0 % attributed to social security costs. These latter charges correspond to the costs incurred by employers in order to secure for their employees entitlements to social benefits, including schemes for pensions, sickness, maternity, disability, unemployment, occupational accidents and diseases, and family allowances, regardless of whether these are statutory, collectively agreed, contractual or voluntary in nature.

The proportion of total personnel costs that is accounted for by social security costs tends to be relatively uniform across activities within a single Member State, as employers' contributions are often set on a statutory basis for the whole economy. As such, the main differences observed for this ratio tend to be across countries. Social security costs accounted for a low share of total personnel costs in Denmark (8.4 %), Cyprus (2005), Ireland, Luxembourg, the United Kingdom and Slovenia (all between 11.9 % and 14.5 %), while their relative importance rose to upwards of 30.0 % in France and Sweden. These costs are often cited (by employers) as impinging on the competitiveness of their enterprises.

Tangible investment

Aside from human capital, enterprises may choose to make other (non-human) tangible investments. Gross investment in tangible goods is defined as investment in new and existing tangible capital goods, whether bought from third parties or produced for own use, having a useful life of more than one year. It should be noted that the level of investment in a particular year is often a volatile measure, in particular at a detailed level, as one year with relatively high investment could be followed by a period with little or no investment.

Figure 6 shows a breakdown of EU-27 investment within the non-financial business economy in 2006 according to the structural business statistics sectoral article headings. Some of the activities at the top of the ranking are characterised by the fact that they rely on networks to function efficiently – for example, some of the transport services, pipelines, the network supply of electricity, gas and steam, or communications. However, the single largest contributor to total EU-27 investment was the real estate, renting and leasing sector (2005): this is perhaps not surprising as many enterprises within these activities are owners of the capital goods that they rent and lease to clients. The other end of the ranking was characterised by relatively small activities (in terms of their contributions to EU-27 value added in the non-financial business economy), in particular, the most labour-intensive manufacturing activities, such as textiles, clothing, leather and footwear as well as furniture and other manufacturing.

Table 2 shows that the highest level of investment in the non-financial business economy was made in France (15.4 % of the EU-27 total), slightly above the shares recorded for the United Kingdom (15.1 %) or Germany (14.4 %). Italy and Spain reported similar levels of investment (just over 10 % of the EU-27 total) and were the only other Member States to register double-digit shares. There was then a considerable gap before the next country in the ranking, namely, Sweden (3.7 %). Poland and Romania (latest data for both countries are for 2005) reported the highest levels of investment among the Member States that joined the EU in 2004 or 2007; both of these countries were over the threshold of 2 % of the EU-27 total.

The investment rate (which is defined as investment divided by value added at factor cost) can be used to identify activities and/or countries that invest relatively high proportions of their added value; this usually occurs when operating margins are relatively wide, perhaps as a result of personnel costs accounting for a relatively low proportion of operating expenditure. Table 3 shows that the average investment rate in the EU-27 in 2006 was 18.4 % for the whole of the non-financial business economy, ranging from a high of 20.9 % for non-financial services, through 16.6 % for industrial activities, to 9.4 % for construction. Investment rates tended to be relatively high in the Member States that joined the EU in 2004 or 2007, in particular Romania (2005), Slovakia and Bulgaria (2005) – where rates rose to above 50 %. Among the EU-15 Member States the highest investment rates were recorded for Denmark and Portugal (just above 28 %).

Productivity

Productivity is often considered as one of the key measure of economic efficiency, showing how effectively economic inputs are converted into output. Apparent labour productivity is defined as the value added generated by each person employed (measured by headcounts): this measure is therefore limited insofar as it does not consider differences in the extent of part-time work across activities. Figure 7 shows that, on average, each person employed in the EU-27's non-financial business economy generated EUR 43.5 thousand of value added in 2006; with apparent labour productivity higher for industrial activities (EUR 54.5 thousand) than for non-financial services (EUR 39.7 thousand) or for construction (EUR 36.2 thousand). Labour productivity tended to be highest among those sectors that are characterised as being capital-intensive, for example, the network supply of electricity, gas and steam, mining and quarrying, fuel processing and chemicals manufacturing (2005), or real estate, renting and leasing (2005). It was lowest among labour-intensive activities, such as the manufacture of textiles, clothing, leather and footwear or accommodation and food services, where labour productivity levels were less than half the non-financial business economy average.

Another measure of productivity is the wage-adjusted labour productivity ratio, defined as value added divided by personnel costs and subsequently adjusted by the share of paid employees in the total number of persons employed, or more simply, apparent labour productivity divided by average personnel costs (expressed as a ratio in percentage terms). Given that this indicator is based on expenditure for labour input rather than a headcount of labour input, it is more relevant for comparisons across activities (or countries) with very different incidences of part-time employment or self-employment. The wage-adjusted labour productivity ratio for the EU-27's non-financial business economy stood at 151.1 % in 2006 (see Figure 8). Among the activity aggregates used for the structural business statistics sectoral articles, the highest ratios were recorded for capital-intensive activities (as was the case for apparent labour productivity), with mining and quarrying and the real estate, renting and leasing sectors at the top of the ranking. At the other end of the range, the wage-adjusted labour productivity ratio was 110 % for research and development (2005).

The ranking of the sectoral articles was generally similar whether based on apparent labour productivity or wage-adjusted labour productivity. However, transport equipment manufacturing moved down from sixth most productive to below the non-financial business economy average, once apparent labour productivity was adjusted for average personnel costs (which were among the highest). On the other hand, motor trades, food, beverage and tobacco manufacturing, and textiles, clothing, leather and footwear manufacturing all moved up the ranking considerably (largely due to the fact that they recorded some of the lowest average personnel costs).

Across the Member States (see Table 4) there were wide ranging differences in apparent productivity levels and average personnel costs; both these ratios tended to be higher among the EU-15 Member States. Ireland reported the highest level of apparent labour productivity for the non-financial business economy, slightly more than 15 times as high as in Bulgaria (data for both of these countries is only available for 2005). The difference in average personnel costs across the Member States were also considerable, as an employee working in the non-financial business economy in Belgium cost almost 17 times as much as someone working in Bulgaria (2005). However, once average personnel costs are used to adjust apparent labour productivity, many of the EU-15 Member States reported relatively low wage adjusted productivity ratios. This was particularly the case in Greece (122.6 %), Italy (133.1 %), France (133.5 %) and Sweden (135.3 %). In contrast, Latvia, Slovakia, Poland (2005) and Bulgaria (2005) each reported wage-adjusted labour productivity ratios of more than 200 % for their respective non-financial business economies in 2006.

Profitability: the gross operating rate

The gross operating rate is defined as the gross operating surplus (value added at factor cost less personnel costs) divided by turnover; it is expressed as a percentage. The gross operating surplus measures the operating revenue that is left to compensate the capital factor input, after labour input has been recompensed. The operating surplus can be used to recompense the providers of funds, to pay taxes, or for self-financing investment. Although not always the case, the gross operating surplus will generally be higher for capital-intensive activities and lower for those activities which have a relatively high proportion of their costs accounted for by personnel. The gross operating rate can be considered as one measure of profitability and is also used as an indicator for measuring competitiveness and enterprise success.

The EU-27’s gross operating rate for the non-financial business economy was 10.8 % in 2006 (see Figure 9), with the rates for industry (10.5 %), non-financial services (10.9 %) and construction (12.0 %) all closely grouped around this broader average. In terms of the activity aggregates used for the sectoral articles, the highest level of profitability in the EU-27 was recorded for real estate, renting and leasing (39.2 % in 2005), followed by mining and quarrying (28.1 %) and media and communications (22.6 %). The lowest EU-27 gross operating rates in 2006 were recorded for distributive trades (in particular, the motor trade and wholesale trade) and for the manufacture of transport equipment.

Across countries, the lowest gross operating rates tended to be recorded among those countries with relatively high personnel costs. Gross operating rates for the non-financial business economies of Belgium, Luxembourg and France did not rise above 8.0 % in 2006, while at the other end of the ranking, gross operating rates exceeded 13 % in Cyprus (2005), Latvia, Poland (2005) and the United Kingdom.

Data sources and availability

The main part of the analysis in this article is derived from structural business statistics (SBS), including core, business statistics which are disseminated regularly, as well as information compiled on a multi-yearly basis, and the latest results from development projects.

Context

Competitiveness at the micro-economic or meso-economic (sectoral level) is often defined as the ability of a particular enterprise or activity to improve its position in (global) markets. Cost structures, investment, as well as productivity levels, may all play a role in determining competitiveness. A high degree of prominence is often given to productivity gains when trying to explain how particular activities or enterprises become more competitive. Productivity levels (or the added value generated by each unit of input) are likely to increase when production factors are re-organised and re-allocated, through the introduction of new processes (in particular those that make use of information and communication technologies (ICT)), increasing the quality of labour inputs (through renewed training and skills development), and making tangible investment in plant and machinery.

Further Eurostat information

Publications

Main tables

Database

Dedicated section

Other information

- COM(2008) 699 - The raw materials initiative: meeting our critical needs for growth and jobs in Europe

See also

- All business economy articles by perspective

- Energy production and imports

- Sectoral productivity at regional level