Archive:Sustainable development - socioeconomic development

- Data from July 2011, most recent data: Further Eurostat information, Database.

This article provides an overview of statistical data on sustainable development in the areas of socioeconomic development. They are based on the set of sustainable development indicators the European Union agreed upon for monitoring its sustainable development strategy. Together with similar indicators for other areas, they make up the report 'Sustainable development in the European Union - 2011 monitoring report of the EU sustainable development strategy', which Eurostat draws up every two years to provide an objective statistical picture of progress towards the goals and objectives set by the EU sustainable development strategy and which underpins the European Commission’s report on its implementation.

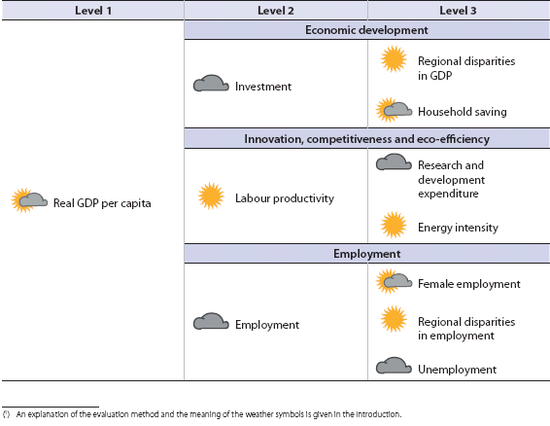

The table below summarises the state of affairs of in the area of socioeconomic development. Quantitative rules applied consistently across indicators, and visualised through weather symbols, provide a relative assessment of whether Europe is moving in the right direction, and at a sufficient pace, given the objectives and targets defined in the strategy.

Main statistical findings

Many of the long-term trends in the socioeconomic development theme have been influenced, either positively or negatively, by the recent global economic and financial crisis. In this respect trends have deteriorated in the short term in particular in investment, employment and unemployment, as well as in real GDP per capita and labour productivity, even if these last two have started to pick up again. On the other hand, improvements have been seen in R&D expenditure and energy intensity, and briefly in household saving.

Headline indicator

GDP per capita

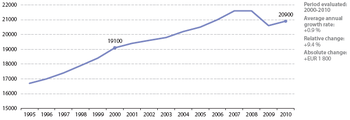

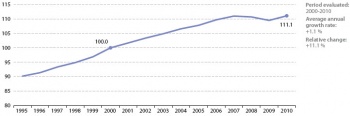

Between 2000 and 2010 real GDP per capita grew in the EU. The 2007 peak in economic growth was followed by a decline in 2009 and slow growth in 2010

- As a result of the crisis, real GDP per capita fell close to the 2005 level in 2009; despite recovery it had not returned to the pre-crisis level by 2010

Real gross domestic product (GDP) per capita grew in every year from 2000 to 2007 until the impact of the global economic and financial crisis began to be felt in 2008. The growth of GDP per capita is a measure of the dynamism of an economy and its capacity to create new jobs. It reflects the phases of the economic cycle. After the economic peak of 2000, GDP per capita grew rather slowly during the economic downturn between 2000 and 2003. This was followed by a period of higher growth rates until 2007. However, with the onset of the crisis, GDP per capita grew by only 0.1 % in 2008 and fell by -4.6 % in 2009 down to a level similar to that of 2005. GDP per capita grew by 1.6 % in 2010, and short-term statistics show 2.2 % growth of GDP in the first quarter of 2011 as compared with the same quarter of the previous year, but only 1.7 % in the second quarter [1].

- Financial crisis has hit particularly fast-growing eastern European Member States

Some countries were hit harder by the economic crisis than others. A large slump in per capita GDP occurred especially in high-growth countries dependent on exports (mostly eastern European Member States whose economic output is expected to ‘catch up’ with that of the more developed Member States). GDP contraction in most western European Members States extended over four or five quarters before growth resumed. The picture has been more varied in eastern European Member States. Particularly affected by the crisis in terms of GDP per capita were Latvia (with the previous GDP per capita growth rate between 2000 and 2007 being 9.4 % on average), Estonia (8.8 %), Ireland (4.1 %), Lithuania (8.1 %) and Finland (3.2 %). However, some eastern European countries (in particular Poland, Bulgaria, Slovakia and Romania) were hit less severely, due in part to lower current account deficits and external debts at the start of the crisis, stricter banking policies, lower dependence on stock exchange performance and exports, more stable domestic demand and modest exchange rate depreciation (in Member States outside the Euro area). A moderate recovery began in 2010 for most EU countries, with the exception of Greece, Ireland, Latvia, Romania and Spain.

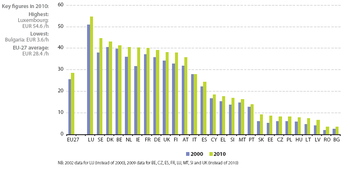

- GDP per capita varies widely across the EU

In 2009, GDP per capita in the EU still varied widely between Member States. Among the countries with GDP per capita, in terms of purchasing power standards (PPS)[2]. higher than the EU average are Luxembourg (by 171 %)[3], Ireland (by 27 %), Netherlands (by 31 %), Austria (by 24 %), Denmark (by 21 %) and Sweden (by 18 %). The countries with the lowest are Bulgaria (lower than the EU average by 56 %, Romania (by 54 %), Latvia (by 48 %) and Lithuania (by 45 %) [4].

Economic development

Investment

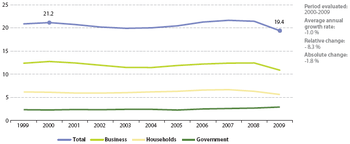

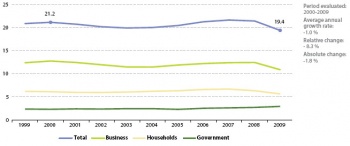

Between 2000 and 2008 the share of investment in the GDP of the EU followed the economic cycle, resulting in a moderate increase, in particular since 2004, but in 2008 and in 2009 development declined

- Business investment has been the main influence on total investment

Investment spending is typically a cyclical and volatile component of GDP growth. During the economic downturn of 2000 to 2003, total investment in GDP fell to a low of 19.9 %, mainly due to a decline in business investment. Since 2003 total investment spending rose steadily, above the growth rate of GDP, as a result of the strong economy fuelling business spending. This led to an investment rate of 21.7 % in 2007, which was higher than in the previous cyclical peak of 2000. Throughout this period the share of public investment in GDP remained relatively stable at around 2.4 %. It was mainly business investment that has influenced total investment.

- In 2008–2009, the crisis’ effects were visible on falling business and household investment spending

As a result of the economic crisis, spending (including inventories) fell during 2008 and 2009. In 2009, the level of 19.4 % was lower than the trough experienced during the previous cyclical low of 19.9 % in 2003. This was mainly a result of sharp cuts in business investment spending (from 12.4 % in 2008 to 10.9 % in 2009) [5], as well as a slight decrease in household investment spending (from 6.7 % in 2007 to 5.6 % in 2009). Government investment spending grew continuously from 2005 by about 6.5 % annually and this development has not been affected by the economic crisis. In fact, in 2008 and 2009 governments around the world reacted with massive economic stimulus packages to effect a turnaround in the world business cycle (in the EU the European Economic Recovery Plan provided an immediate stimulus package amounting to 1.5 % of EU GDP). Nevertheless, some countries with vital business sectors not severely affected by the economic crisis (in particular Austria, Belgium and Slovakia) managed to keep total investment spending above the EU average even with low levels of government investment.

- Modest changes in investment rate reflect fluctuations in business investment

During the economic downturn of 2000 to 2003, the share of total investment in GDP fell to a low of 19.4 %, due to the slower development of business investment. Since 2003, total investment spending has been steadily rising at a higher rate than GDP as a consequence of expanded business spending fuelled by favourable economic conditions, resulting in an investment rate of 21.3 % in 2007. This amount is 0.7 percentage points higher than in the previous cyclical peak of 2000. As the share of public investment in GDP has remained stable since 2000 at around 2.4 %, it is mainly business investment which has made the difference in influencing total investment.

- Stimulus packages to restore confidence

Not surprisingly, in the light of the current economic crisis and because investment spending is typically a strongly cyclical and volatile component of GDP growth, forecasts for the next years show a considerable cutback in total investment down to 19 % of GDP in 2010. Despite the considerable uncertainty in these forecasts, the projection for 2009 is supported by recent data which show a sharp decline of 10.7 % of seasonally adjusted gross investment in the first quarter of 2009 compared to the previous year (10). In order to anti-cyclically compensate for the foreseeable decline in business investment, cohesion policy, which is aimed at strengthening public investment, especially in the economically least-developed regions (11), has been re-emphasised in the European Economic Recovery Plan. Cohesion policy is planned to account for almost 6 % of expected GDP on average over the period 2007 to 2013. The envisaged measures are intended to stimulate private investment and consumption by restoring business and consumer confidence in the economy.

Regional disparities in GDP

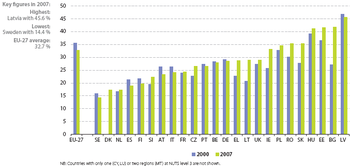

Between 2000 and 2007 disparities in GDP per capita between the regions of the EU decreased, indicating that economic wealth is becoming more equally distributed

- Disparities in GDP between regions have fallen

Within-country dispersion rates of regional GDP in the EU, which is a measure of the equality of distribution of economic activity among a country’s regions, fell between 2000 and 2007 from 35.5 % to 32.7 % [6].

- Dispersion of regional GDP is highest in eastern European countries

In 2007, most countries with disparities higher than the EU average were eastern European. The rapid transition into market economies has apparently led to a polarisation of economic output and an uneven distribution of wealth between regions. Between 2000 and 2007, the within-country dispersion rate of regional GDP rose in 15 out of 24 Member States. Despite growing regional disparities in many countries, the decrease at EU level is likely to be due to declines in Member States with large populations (Spain, Italy and Germany).

Although the indicator presented here refers to NUTS level 3; the trends between 2000 and 2007 are consistent for both NUTS levels 2 and 3.

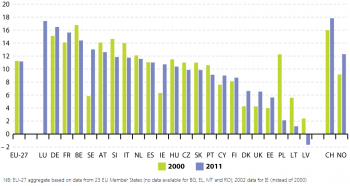

Household saving

Between 2000 and 2010 the share of saving in the disposable income of EU households increased slightly. Although the rate fell between 2001 and 2007, it improved sharply during the economic crisis in 2008 and 2009 and in 2010 fell close to 2003 level

- Economic crisis has manifested in a sharp increase in household saving rate

In response to the economic downturn over the years 2001 to 2003, the household saving rate climbed to 12.3 % in 2001 and then fell modestly during the economic upturn until 2007, when it reached a low of 10.9 %. It started to rise again in 2008 and rose sharply during the crisis year of 2009 to 13.2 %. Such sharp increases reflect a lack of confidence by households in the immediate future of the economy and an attempt to protect their long-term assets in view of low interest rates. This was especially the case during the economic crisis when the real disposable income of households decreased [7]. The fall of the household saving rate in 2010 fits the expectation that it will not continue to rise further and will most probably gradually return to pre-crisis levels [8]

Between 2000 and 2009, the household saving rate varied significantly across EU Member States. As can be seen in Figure 1.9, particularly in Baltic countries and the UK, the average household saving rate was very low (less than half the EU average). Numerous factors can help explain country differences in household saving rate, such as income taxes, inflation, the pension system, stock and housing prices, real interest rate, female employment rate or the volume of shadow activities. In 2009, the saving rate across EU Member States ranged from around 6 % (6 % in UK, 7.9 % in Lithuania) to above 18 % (18.1 % in Spain, 18.3 % in Belgium).

Innovation, competitiveness and eco-efficiency

Labour productivity

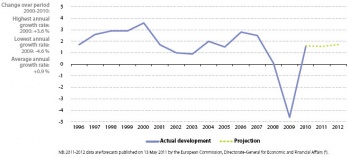

Between 2000 and 2010 labour productivity in the EU improved, although the economic crisis in 2008 and 2009 reversed this trend, the levels of 2007 were reached in 2010

- After several years of growth, labour productivity in the EU fell in 2008 and 2009, the levels of 2007 were reached in 2010

- Eastern European countries experienced high labour productivity gains in 2000-2010

Labour productivity in the EU rose steadily between 2000 and 2007. In 2007, it began to fall in Denmark, France and Sweden, even if it continued to grow in Bulgaria, Estonia, Ireland, Spain, Cyprus, Slovakia, Portugal and Poland. Falls in productivity during the economic crisis were mostly the result of firms not laying off workers as much as expected (as a result of labour hoarding and strengthened shortterm employment protection legislation in many Member States reducing labour market flexibility and resulting in work-sharing and reducing working hours per worker instead of layoffs) but also slower capital accumulation [9]. However, the economic upturn of 2003 to 2007 has not led to above average increases in labour productivity growth. This can be explained by factors such as declining investment per employee, slowdown in the rate of technological progress, sluggish reorientation of the economy toward sectors with high productivity, the relatively small size of the EU’s information and communication technology industry [10] and a stagnating share of R&D expenditure in GDP (see indicator on ‘R&D expenditure’).

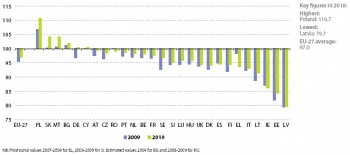

Between 2000 and 2010, labour productivity grew sharply in Member States that were in the process of economic transition and with high GDP growth rates: Romania (74.7 %), Latvia (65.2 %), Slovakia (55.8 %), Estonia (60.1 %), Lithuania (56.6 %), Poland (35.0 %) and Hungary (32.6 %).

Research and development expenditure

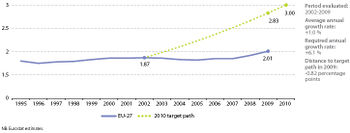

During the period 2002 to 2009 spending on research and development in the EU grew slightly as a share of GDP, but not fast enough to be on track towards the target of 3 % by 2010

- Despite the crisis and long-term inertia R&D spending improved in 2008 and 2009

The share of research and development spending (R&D spending) as a percentage of GDP remained between 1.8 % and 1.9 % over the period 2000 to 2007, making no significant progress towards the EU SDS target of raising investments in R&D to 3 % by 2010. Over 2008 and 2009, R&D spending slightly grew to 2.0 %. This value remains below the OECD average of 2.3 %, as well as below the shares of USA (2.8 %) and Japan (3.4 %) (2008 data) [11].

In 2009, Finland and Sweden continued to lead with a share of 4.0 % and 3.6 % respectively, which also puts them in a world-leading position after Israel (4.3 % in 2009) (16). Austria, Denmark and Germany all stood between 2.8 % and 3.0 %. In addition, many of the countries that lag behind increased R&D spending significantly between 2000 and 2009, including Cyprus, Estonia and Portugal. All of these had almost doubled the percentage of GDP spent on R&D. However, some countries cut spending; the most marked was Slovakia which reduced its R&D budget from 0.7 % to 0.5 % over this period.

- R&D is crucial for long-term growth based on knowledge and innovation

It would also seem that, as a way out of the economic crisis, some countries have attempted to support economic recovery and longer-term growth by boosting public and private funding of R&D. Germany, Denmark, Finland, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Portugal and Slovenia increased their R&D spending in 2007 or 2008 contributing to the slight growth of the EU average towards the end of the 2000–2009 period. In some cases these increases were quite substantial, e.g. between 2007 and 2009 the spending on R&D grew by 37.2 % in Ireland and by 42 % in Portugal. However, due to pressure on public and private financial resources, the economic crisis has also resulted in cuts in R&D funding, especially in Latvia and, to a smaller extent, Romania, where R&D expenditures were already rather low.

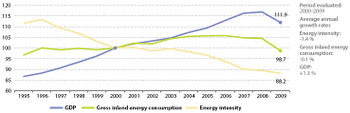

Energy intensity

The energy intensity of the EU fell significantly between 2000 and 2009. Due to overall GDP growth and a drop in energy consumption over the same period an absolute decoupling has been achieved

Absolute decoupling of energy consumption from economic growth has been achieved between 2000 and 2009.

- Over the period 2003 – 2009 the annual average growth rate for gross inland energy consumption fell by 0.9 %

Energy intensity is strongly linked to the economic cycle. Thus energy intensity decreased from 1996 to 2000, remained almost constant from 2000 to 2003 and fell again from 2003 to 2009. This is a result of GDP growth slowing faster than gross inland energy consumption during economic downturns. The overall decline in energy intensity by almost 12 % has been enough to meet the 1 % average yearly reduction target [12] despite only minor improvement during the downturns.

Viewed in more detail, between 1995 and 2000 energy intensity fell by 2.1 % per year on average (GDP grew by 2.9 % per year while gross inland energy consumption increased by 0.7 % per year on average). Between 2000 and 2009 energy intensity continued to fall, by 1.4 % per year on average (GDP rose by 1.3 % per year and gross inland energy consumption decreased by 0.1 % per year on average).

The least energy-intensive economies in the EU are Denmark, Ireland and the UK. Among the most energy-intensive economies are Bulgaria, Romania, Estonia, the Czech Republic and Slovakia. In socialist times, eastern European Member States had economies with high shares of energy-intensive industries as well as an energy-inefficient infrastructure serving these industries. They have been undergoing the transition to economies based more on services or higher value-added production as well as the process of industrial modernisation.

Employment

Employment

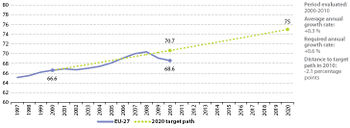

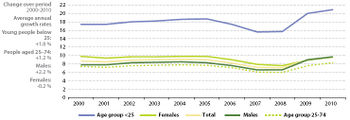

Following an increase in employment rates between 2000 and 2008 they fell in 2009 and 2010, making it harder to reach the target level of 75 % by 2020

- Until 2008 employment in the EU was well on track towards the 2020 target

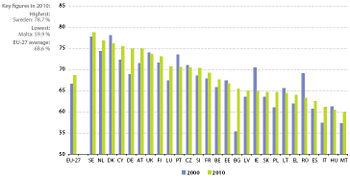

Between 2000 and 2008, employment among 20 to 64 year olds in the EU rose from 66.6 % to 70.4 % and was on track to meet the 75 % target for 2020. Its development reflected the economic cycle, albeit with some time lag, and prior to the crisis the employment rates were even above the target path. The economic crisis had a pronounced effect when in 2009 the employment rate fell to 69.1 % – below the 2006 level. The employment rate has continued to fall since then, reaching 68.6 % in 2010. Some Member States reacted by reducing working hours and creating public sector jobs [13].

Differences between EU Member States are large. The Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark, Cyprus, Germany and Austria are all close to or even above the 75 % target, while Malta, Hungary, Italy, Romania, Spain, Greece, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia and Ireland are all below 65 %.

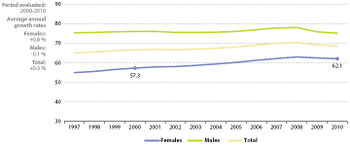

- The economic crisis was hardest on men and the less educated

Men were harder hit than women, experiencing a fall in employment of 2.2 % in 2009 compared with a fall of 0.8 % for women (see following indicator). In 2010 the employment rate continued to fall by 0.7% for men and 0.4 % for women. Young people aged between 15 and 24 were particularly vulnerable as well as immigrants [14]. However, the employment rate of older people between 55 and 64 years was not affected and continued to grow, standing at 45.6 % in 2008, 46.0 % in 2009 and 46.3 % in 2010, as compared with 36.8 % in 2000 [15].

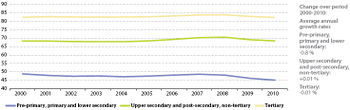

- Higher education gives better chances on the job market

The employment rate is greater for those with higher education levels. Since 2000, more than four-fifths of 25 to 64 year olds with a tertiary-level educational qualification have been employed compared with less than half of those with lower secondary education. The relative employment rates for the different education subgroups have evolved in parallel over time. People with lower education levels were the most vulnerable to job losses, which may be explained by loss of jobs in sectors largely requiring lower qualification, e.g. the construction sectors of Spain, UK and Ireland. In 2009, the employment of people with completed primary and lower secondary education fell by 4.0 %, for those with upper and post-secondary education it fell by 2.1 %, and for those with tertiary education it fell by 1.2 %. The decreases in employment rate continued in 2010.

Female employment

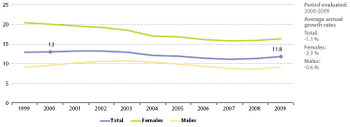

Between 2000 and 2008 female employment in the EU rose steadily, but from 2009 it started to fall. The gap between male and female employment continued to shrink even during the economic crisis, which hit men more than women

- Female employment is gradually converging with that of men

Over the period 2000 to 2008, female employment rose continuously, closing the distance to male employment. This convergence was less strong during the economic upturn from 2005 to 2007 when more jobs were created, than when economic conditions were weaker from 2000 to 2003 and since 2008. In 2008 the female employment rate (of women aged 20 to 64) was 63 %, but declined slightly in 2009 to 62.5 % and in 2010 reached 62.1 %. The crisis affected men more than women, helping to further narrow the employment gender gap.

Considerable differences remain between Member States. In 2010 female employment ranged from 41.4 % in Malta, 49.5 in Italy and 51.7 % in Greece to 70.8 % in the Netherlands 71.5 % in Finland, 75.7 % in Sweden and 76.9 % in Norway.

Regional disparities in employment

Between 2000 and 2009 disparities in employment rates between regions were reduced, although showing a slight upturn in 2008 and 2009

- Reduction of regional disparities coupled with economic upturn

The dispersion of regional employment grew slowly between 1999 and 2003, before falling steadily from 2003 to 2007 due to favourable economic conditions. In 2007 the indicator stood at 11.1 %, which is a significant decrease from the 13.0 % in 2000. Between 2000 and 2007, disparities were reduced in 12 of the 18 EU Member States for which the indicator was calculated. This may have been caused by factors such as a more mobile workforce, diminishing sectoral specialisation of regions, and diminishing regional differences in educational attainment and skills. However, over 2008 and 2009 disparities increased to 11.8 %. In 2009, 18 of 19 Member States reported dispersion of regional employment rates within their territories that were below the dispersion within the EU as a whole (Italy being the exception).

- Women finding a stable position in regional economies

Dispersion of male employment (from 9.6 % in 2000 to 9.1 % in 2009) was not as marked as that of female employment (from 20 % in 2000 down to 16.3 % in 2009). However, the gradual fall of the dispersion of female employment indicates that the position of women is becoming more stable in regional economies.

Disparities are higher at NUTS 3 level than at NUTS 2 level, as at NUTS 3 level the differences between ‘sub-regions’ (which sometimes have large variability) within each NUTS 2 level are taken into account.

Unemployment

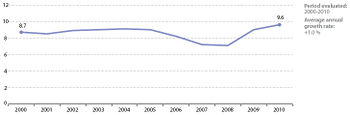

Due to a sharp increase caused by the current economic crisis, unemployment in the EU in 2010 was higher than in 2000. Gender disparities decreased towards 2010, but unemployment of young people remains a problem

- Unemployment follows economic cycles with a time lag

Unemployment increased in the EU between 2001 and 2003 from 8.5 % to 9.0 %, lagging one year behind the economic downturn. It fell between 2005 and 2008 to 7.1 %, a level well below the previous economic cycle’s low point. However, in 2008, the unemployment rate rose in ten Member States and over 2009, despite job-stabilisation measures and the European Economic Recovery Plan it rose significantly across the whole EU. The most affected, in percentage terms, by the increase in 2009 were Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania, where unemployment leaped by 8 to 10 percentage points, but also Spain and Ireland, which experienced a rise in unemployment by 4 to 7 percentage points. In 2010, the unemployment rate fell in Malta and Luxembourg, although in most countries it continued to grow slightly, reaching 9.6 % in 2010, the highest value for the EU since 2000. Further increases in structural unemployment can be expected as some sectors affected by the crisis might potentially be downsized or relocated [16].

- Young people, men, low-skilled workers and immigrants hit most by the economic crisis

Unemployment by age and gender show the labour market situation is worst for young people aged 15 to 24. More than 20 % of people in that group were unemployed throughout the second half of 2009 and 2010. This is more than twice as high as the overall rate. The gender gap in unemployment fell dramatically from 2.0 % in 2000 to 0.1 % in 2010.

Further information

Publications

Database

- Indicators

- Socioeconomic Development

Dedicated section

Methodology

More detailed information on socioeconomic development indicators, such as indicator relevance, definitions, methodological notes, background and potential linkages, can be found on page 47-79 of the publication Sustainable development in the European Union - 2011 monitoring report of the EU sustainable development strategy.

Other information

- Cohesion policy - investing in the real economy, Commission communication COM(2008) 876

- Renewed social agenda: opportunities, access and solidarity in 21st century Europe, Commission communication COM(2008) 412

- A shared commitment for employment, Commission communication COM(2009) 257

- GDP and beyond: Measuring progress in a changing world, Commission communication COM(2009) 433]

- European Competitiveness Report 2010, Commission staff working document SEC(2010) 1276

- Eurostat, Science, Technology and Innovation in Europe, Luxembourg, Office for Official Publications of the European Union 2010

- Eurostat, The Social Situation in the European Union 2009, Luxembourg, Office for Official Publications of the European Union, 2010

- Eurostat, European economic statistics, 2010 edition, Luxembourg, Office for Official Publications of the European Union 2011

- Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress, 2009

- Analysing and measuring social inclusion in a global context, United Nations publications, New York, 2010

See also

Notes

- ↑ Eurostat news release, Euro-indicators 118/2011, Euro area and EU27 GDP up by 0.2%, 16 August 2011

- ↑ The Purchasing Power Standard (PPS) is an artificial reference currency unit that eliminates price level differences between countries. One PPS buys the same volume of goods and services in all countries. This unit allows meaningful volume comparisons of economic indicators across countries. Aggregates expressed in PPS are derived by dividing aggregates in current prices and national currency by the respective Purchasing Power Parity (PPP). The level of uncertainty associated with the basic price and national accounts data, and the methods used for compiling PPPs imply that differences between countries that have indexes within a close range should be interpreted with care

- ↑ The high level of GDP per capita in Luxembourg is partly due to the large share of cross-border workers in total employment. While contributing to GDP, they are not taken into consideration as part of the resident population which is used to calculate GDP per capita

- ↑ See the Structural Indicator ‘GDP per capita in PPS’ tsieb010on the Eurostat website.

- ↑ Worldwide, business investment spending started recovering about mid-2010. However, a slower recovery is predicted for the EU than Japan and USA. See for example Eurostat news release, Euro-indicators 161/2010, Business investment rate up to 20.4 % in the euro area and 19.9 % in the EU27, 28 October 2010fckLRand OECD Factblog, Business returns, 19 November 2010.

- ↑ Regional disparities of GDP will probably have been negatively affected by the economic crisis of 2008 and 2009

- ↑ Household real disposable income started to fall in some countries already in the first quarter of 2008 and has continued to fall until 2010. The reason was that nominal incomes of households fell slightly, mostly due to rising unemployment, and the prices of goods and services they consume grew. See also Eurostat news release, Euro-indicators 111/2010, Household saving rate down to 14.6% in the euro area and 13.0% in the EU27, 29 July 2010 and Eurostat news release, Euro-indicators 14/2011, Household saving rate down to 13.8% in the euro area and 11.5% in the EU27, 28 January 2011.

- ↑ Commission staff working document, European economic forecast – autumn 2009, European Economy 10/2009.

- ↑ European economic forecast – autumn 2010, ibid.

- ↑ Commission communication, Second Implementation Report on the 2003-2005 BEPGs, COM(2005) 8; Timmer, M.P. and van Ark, B., ‘Does information andfckLRcommunication technology drive productivity growth differentials? A comparison of the European Union countries and the United States’, Oxford EconomicfckLRPapers, 57(4), 2005, pp. 693-716.

- ↑ Organisation for Economic Co-operation and development, Main science and technology indicators, vol. 2010/1, Paris, 2010

- ↑ Commission communication Energy efficiency in the European Community – Towards a strategy for the rational use of energy, COM(1998) 246

- ↑ International Labour Office, EU: heterogeneous shocks and responses across countries (G20 Statistical Update), prepared for the G20 Meeting of Labour andfckLREmployment Ministers, 20–21 April 2010, Washington DC

- ↑ (20) OECD Factblog Immigrants take the brunt of the jobs crisis 20 July 2010

- ↑ See the headline indicator ‘employment rate of older workers’ in the chapter on ‘demographic changes

- ↑ European economic forecast – autumn 2009, ibid.