Archive:Youth unemployment

This article explains how youth unemployment is measured and how youth unemployment rates are affected by the transition of young adults from education to the labour market. Two factors are particularly relevant. First, there is a steep increase of labour participation between the age of 15 and 24. Secondly, young persons in education often are simultaneously employed or unemployed, meaning that there is an overlap between labour market and education.

This article is focused on measures of youth unemployment. The interplay between education and labour market participation is further developed in a separate article (Participation of young people in education and the labour market).

Unemployment definition and youth unemployment indicators

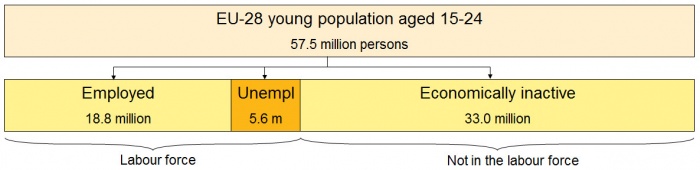

Persons are classified by their labour force status into three categories: employed, unemployed or economically inactive. Eurostat follows the employment and unemployment definitions of the International Labour Organisation (ILO). The labour force, also called active population, is the population employed or unemployed. These concepts are explained in full detail under EU - LFS methodology. These definitions are applied to young adults in the same way as to any other age group.

People are classified in employment or unemployment independently of whether they are in education or not. Otherwise said, Eurostat unemployment statistics, in line with ILO standards, do not exclude students from unemployment by the mere fact of being students. The same unemployment criteria are applied to them as to the rest of the population. This means that the status in education of any given individual is irrelevant for his/her status in employment or unemployment. However, participation in education of the population as a whole has an indirect effect on youth unemployment indicators, as will be shown below.

The main indicator of youth unemployment is the youth unemployment rate for the age group 15-24. It uses the same standard definition as the unemployment rate for the working age population: for a given age group, it is the number of unemployed divided by the persons in the labour market (employed plus unemployed). In the EU28 in 2012 there were on average 5.6 million unemployed persons aged 15-24 and 24.4 million persons of that age group in the labour market, according to the EU Labour Force Survey. This gives a youth unemployment rate of 23.0%.

Because not every young adult is in the labour market the youth unemployment rate does not indicate the share of all young adults who are unemployed. Youth unemployment rates are frequently misinterpreted in this sense, a 25% youth unemployment rate does not mean that '1 out of 4 young persons is unemployed'. This is a common fallacy. Also, the youth unemployment rate may be high even if the number of unemployed persons is limited; that may be the case when the young labour force (i.e. the rate's denominator) is relatively small. This is not an issue for the unemployment rate of the whole working age population due to the higher participation of population in the labour market (43% at ages 15-24 compared to 85% at ages 25-54, 2012 EU28 estimates)

Another indicator of youth unemployment published by Eurostat is the youth unemployment ratio. It has the same numerator as the youth unemployment rate but the denominator is the total population aged 15 to 24. It thus gives an unemployment-to-population measure. The size of the youth labour market (i.e. the size of the young labour force) does not trigger effects in the youth unemployment ratio, contrary to the unemployment rate.

In the EU28 in 2012 there were 57.5 million persons aged 15-24, of which 5.6 million were unemployed. This gives a youth unemployment ratio of 9.7%. Table 1 reports youth unemployment rates alongside youth unemployment ratios for 2012. Data are based on the EU Labour Force Survey.

The youth unemployment ratio is by definition always smaller than the youth unemployment rate, typically less than half of it. This difference is entirely due to the different denominators.

Yet another measure is the proportion of young people not in employment and not in any education and training (NEET). The NEET rate includes two groups in the numerator: a) those youth unemployed who are not in education; b) other young persons not in the labour market nor in education/training. Note that those young persons who are simultaneously unemployed and in education are not included in this indicator. The denominator is the same as the unemployment ratio, i.e. it is the whole young population. The purpose of the NEET is to measure the young people who have already left the educational system but who are not on the labour market, encompassing also discouraged jobseekers who gave up looking for work. This definitional change has the outcome of also including persons who are on a volunteer career break. With regard to that the choice of the target age group for the indicator is important in this respect.

Young persons' participation in the labour market

As explained above, unemployment rates and unemployment ratios differ because the former include in the denominator only the part of the population that is in the labour market. There is also a strong link between labour market participation and status in education, which becomes particularly clear when looking at young people's situation at different years of age. This section analyses this issue in more detail.

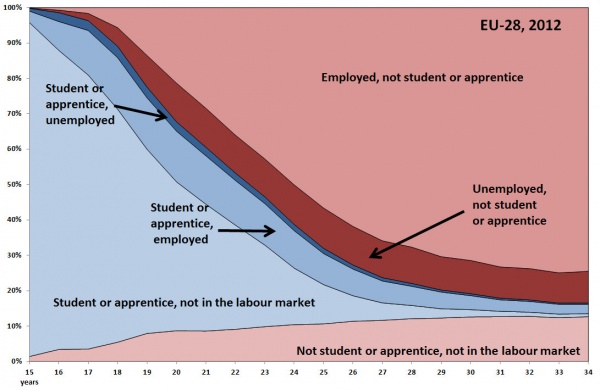

At 15 years of age, virtually 100% of the population in the EU are still at school. As the young grow older, many move into the labour market, becoming employed or unemployed, or remain outside the labour market. This transition does not happen at the same age to everybody, resulting in a gradual increase of the young population in the labour market. Chart 2 below shows the share of young people participating in education and/or in the labour market at each year of age (data for EU28, 2012). Persons in education are colour-coded in blue, and those not in education in pink. There is a steep change in labour market participation from some 5% at 15 years of age to some 80% at 24. This steep increase explains the difference between the youth unemployment rates and youth unemployment ratios, introduced in the previous section. This is a distinctive feature of the young population and it has no equivalent at other ages, exception made of the gentle decrease of labour participation by older workers as they retire. Chart 2 is based on EU Labour Force Survey data. Chart 2 considers in education every person that has indicated to have participated in formal education or training during the last 4 weeks.

A second feature in Chart 2 is that many young people join the labour market before they finish their studies or they participate in education while already in the labour market. This means that people can be simultaneously in education and in the labour market. (It is noted that participation in the labour market, according to ILO definitions, occurs by working as little as 1 hour in the week, or looking and being available for such work). Otherwise said, those in education and those in the labour market are not always different groups, an overlap exists. The transition from education to the labour market is not a simple switch of status but a complex overlap of different situations. This is developed in a separate Statistics Explained article (Participation of young people in education and the labour market).

Chart 2 shows that most young unemployed are not in education, but many are (respectively 4.3 million and 1.3 million persons aged 15-24, in the EU28 in 2012). There are also many young employed while in education (6.7 million). As can be seen, there are more young employed in education than young unemployed (whether in education or not).

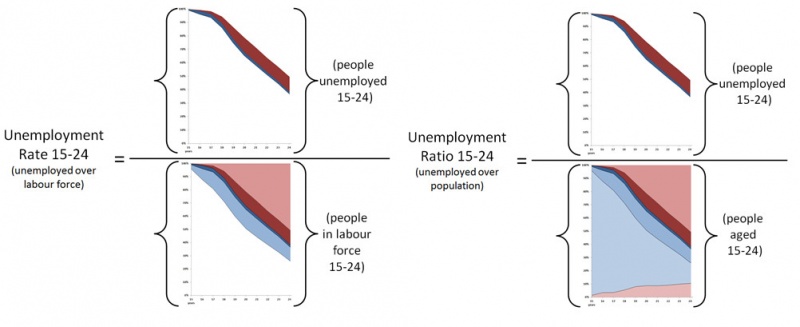

Chart 3 below shows visually which groups are involved in the calculation of the youth unemployment rate and youth unemployment ratio. It is a visual presentation of the definitions described in Chart 2 above.

As can be seen, both indicators use the same numerator but the denominators differ.

The interplay between education and labour market participation is further developed in a separate article (Participation of young people in education and the labour market).

The effects of the crisis on youth unemployment

The economic crisis has had effects that go beyond an important increase of youth unemployment. Video 1 below shows a sequence of charts like Chart 2 to visualise the changes in one specific country, Spain, between 2007, immediately before the onset of the crisis, and 2012.

First, it can be seen that the share of population in education at a certain age has increased, meaning that young adults remain longer in education before joining the labour market or even return to education. This is visible from the border between the areas colour-coded in blue and red moving upwards. Secondly, since 2007 the share of employed in education and the unemployed in education increased. Together they account for a small increase of the share of persons who, at the same time, are in education and in the labour market (area blue-coded). Part of it could be due to unemployed persons that return to (or remain in) education while primarily focused on finding a job. The biggest change in Spain, however, is the surge of young unemployed not in education, at the expense of a decrease of the employed not in education (area pink-coded). These patterns are also similar in other countries strongly hit by the crisis.

Secondly, since 2007 the share of employed in education and the unemployed in education increased. Together they account for a small increase of the share of persons who, at the same time, are in education and in the labour market (area blue-coded). Part of it could be due to unemployed persons that return to (or remain in) education while primarily focused on finding a job. The biggest change in Spain, however, is the surge of young unemployed not in education, at the expense of a decrease of the employed not in education (area red-coded). These patterns are also similar in other countries strongly hit by the crisis.