Statistics on continuing vocational training in enterprises

Data extracted in November 2022.

Planned article update: 2027.

Highlights

In 2020, 67.4 % of enterprises in the EU Member States with 10 or more persons employed provided continuing vocational training to their staff.

This article presents statistics on vocational training in enterprises in the European Union (EU) and forms part of an online publication on education and training in the EU. It highlights results from the continuing vocational training survey (CVTS) which collects quantitative as well as qualitative information on the provision of continuing vocational training (CVT) by enterprises, as well as some information on initial vocational training (IVT). Looking at such data is interesting because it gives information on how enterprises invest in the skills’ development of their staff. The CVTS is carried out every five years, and the most recent reference year 2020 is of particular interest as it reflects the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on training in enterprises: compared to 2015, fewer enterprises provided CVT, there were fewer participants and the training was more costly.

Information from the CVTS refers to education or training activities which are financed, at least in part, by enterprises. Part financing could include, for example, the use of work time for the training activity. CVT can be provided either through dedicated courses or other forms of CVT, such as guided on-the-job training. In general, enterprises finance CVT in order to develop the competences and skills of the people they employ, expecting that this may contribute towards increasing competitiveness and productivity. A large majority of CVT is non-formal education or training, in other words, it is provided outside the formal education system. Only enterprises from the business economy are included in the analysis; in other words, most economic activities are covered, with the exclusion of agriculture, forestry and fishing, public administration and defence, compulsory social security, education, human health and social work activities.

Full article

How many enterprises provide CVT to their staff?

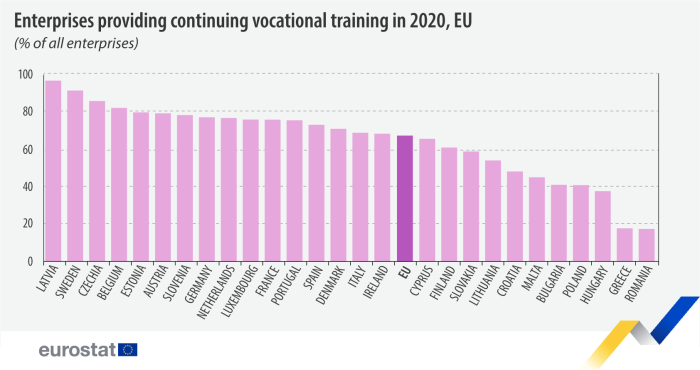

In 2020, 67.4 % of enterprises employing 10 or more persons in the EU were ‘training enterprises’, i.e. they provided either CVT courses or at least one of the other forms of CVT to their staff (such as guided on-the-job training, learning cycles, self-directed learning, etc., see Figure 1). This marked a decrease compared with 2015 when the corresponding share was 70.5 %, a peak after 63.6 % in 2010. This decrease in 2020 can most likely be explained by reduced business activity, lockdowns and restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Among the EU Member States, the share of enterprises that provided any form of CVT in 2020 ranged from 17.5 % in Romania to 96.8 % in Latvia; note that this share was also very high in Norway (93.0 %).

(% of all enterprises)

Source: Eurostat (trng_cvt_01s)

Looking at the ratio of CVT courses vs. other forms of CVT, enterprises in the EU were slightly more likely to provide CVT through courses (either internal or external) than to provide only any of the other forms of CVT in 2010 and 2015 while other forms of CVT gained importance in 2020. This could also be a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, due to the difficulties of organising CVT courses in enterprises.

Studying the distribution of CVT types in training enterprises in 2020, 14.9 % of EU enterprises provided only CVT courses, 48.7 % provided only other forms of CVT and 36.4 % provided both - see Figure 2. The proportion of enterprises providing CVT courses including together with other forms of CVT exceeded 80.0 % in Czechia and was also above the EU average of 51.3 % in Austria, Luxembourg, Sweden, France, Italy, Cyprus, Germany and Belgium. In contrast, less than one quarter of enterprises provided CVT courses (along with other forms) in Latvia, Romania and Greece. The proportion of enterprises providing other forms of CVT had a wider range, with 14 countries having 90 % or more of this type of training (either only other forms of CVT or along with CVT courses): Poland, Croatia, Portugal, Hungary, Estonia, the Netherlands, Cyprus, Bulgaria, Germany, Sweden, Ireland, Slovenia, Malta and Latvia; the share recorded in Norway was also relatively high (at 90.8 %).

What are the characteristics of enterprises providing CVT? Analyses by economic activities and size

Within the EU, enterprises in services (other than distributive trades or accommodation and food services) were more likely to provide CVT. This was particularly the case for the grouping of information and communication services and financial and insurance activities where the proportion of training enterprises in 2020 was 82.8 %. Only enterprises in industry (except construction) saw an increase in the share of training enterprises in 2020 compared to 2015, while enterprises in all other groupings of economic activities reported a decrease between 2 and 5 percentage points (p.p.) - see Figure 3.

(% of all enterprises)

Source: Eurostat (trng_cvt_01n2)

On average, enterprise size appears to be a fairly relevant factor regarding the provision of CVT across the EU. In 2020, 92.8 % of large enterprises (with 250 persons employed or more) provided continuing vocational training, compared with 82.5 % of medium-sized enterprises (with 50–249 persons employed) and only 63.5 % of small enterprises (with 10–49 persons employed), see Figure 4. It is interesting to note that this pattern is followed in all countries but the magnitude can vary a lot: in Latvia, the difference between small and large enterprises is only 1.5 p.p. while it represents 53.0 p.p. in Hungary.

(% of all enterprises)

Source: Eurostat (trng_cvt_01s)

How many employed people participate in CVT courses?

The data on participation rates in Figure 5 only relate to participation in CVT courses and not to participation in other forms of CVT. In the EU in 2020, 42.4 % of persons employed in all enterprises participated in CVT courses. Thus, looking at the business economy as a whole, compared to 2015, the participation rate decreased by only 0.5 p.p. in the EU.

Across the EU Member States, participation rates ranged from 82.8 % in Czechia to 11.8 % in Greece and hence varied by a factor of 7. All EU Member States saw a decrease in 2020 compared to 2015, except Lithuania, Latvia, Germany and Spain. At the same time, participation rates in 2020 were still higher than in 2010 in 17 of the countries for which the comparison is possible.

(% of persons employed in all enterprises)

Source: Eurostat (trng_cvt_12s)

How much do CVT courses cost?

As for participation rates, data on cost only relate to CVT courses and not to other forms of CVT. The data on the cost of CVT courses (as shown in Figure 6) have been converted to purchasing power standards (PPS) rather than presenting these costs in euros. Purchasing power standards are a theoretical currency which adjusts for price level differences between countries.

In 2020, the average expenditure on CVT courses by training enterprises in the EU was 1 441 PPS per participant. Note that each person is counted once, regardless of how many courses they attend during a year and regardless of the course duration. The average cost per participant in CVT courses ranged from 320 PPS in Czechia to 2 315 PPS in Ireland, with the Netherlands (2 262 PPS), France (1 920 PPS), Germany (1 678 PPS), Denmark (1 628 PPS), Italy (1 505 PPS) and Sweden (1 485 PPS) above the EU average.

For a comparison of the cost of CVT courses over time, Figure 7 shows the cost in euro per training hour. In 2020 in the EU, the cost for one hour of CVT course was 64 euros, just one euro more than in 2015. The hourly cost was highest in France (91 euros), Sweden (87 euros) and Ireland (86 euros) and lowest in Portugal (20 euros), Bulgaria (16 euros) and Romania (14 euros). When looking at euros, a training hour was the most expensive in Norway, with 94 euros.

Compared to 2015, for the 26 EU Member States for which the comparison is possible, the hourly cost increased in 16 countries (from just 1 euro to as much as 38 euros) while it stayed the same in 3 countries or even decreased in 7 countries (from -1 to -15 euros). Compared to 2010, the hourly cost increased in most countries and only decreased in Croatia, Finland, Germany, Portugal, Greece and Hungary.

(euro)

Source: Eurostat (trng_cvt_20s)

What are the reasons limiting the provision of CVT?

As noted above, 67.4 % of EU enterprises provided some form of CVT in 2020, and consequently 32.6 % did not. It is therefore of interest to look at the reasons that either limited training enterprises to provide more CVT or non-training enterprises to provide any CVT at all.

Concerning EU enterprises that provided CVT in 2020, 40.5 % of these enterprises indicated that the level of the training provided was appropriate to the needs of the enterprise (i.e. no limiting factors) - see Figure 8. This was a considerably lower share compared to 2015 (45.2 %) and 2010 (51.0 %). 40.6 % of training enterprises indicated that their preferred strategy was to recruit individuals with the required qualifications, skills and competences in 2020, which is about the same share as in 2010 but more than 5 p.p. lower than in 2015. Difficulties for providing training due to COVID-19 could partly explain this evolution.

The most frequently named limiting factors were lack of time for staff to participate (36.8 %) and high cost of courses (23.4 %) but both categories lost importance compared to 2015 and 2010. At the same time, the share of the category ‘other reasons’ increased by a factor of 2.6 compared to 2015, and these changes are most likely due to the particular circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 where companies faced other challenges in providing training compared to pre-pandemic times.

(% of training enterprises)

Source: Eurostat (trng_cvt_03s)

Looking at non-training enterprises in the EU, the two main reasons given for not providing CVT related to recruitment strategies and existing skills: almost half (48.1 %) of the non-training enterprises did not provide CVT because they tried to recruit people with the required skills while three quarters (74.7 %) said that the existing skills and competences of their workforce already corresponded to their needs - see Figure 9. A lack of time was the third most common reason, given by around 3 in 10 enterprises not providing training, a share that remained relatively stable since 2010. Just as for training enterprises, the high cost of courses lost importance compared to previous years while the category ‘other reasons’ scored far higher in 2020, again most likely due to the particular challenges brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic.

(% of non-training enterprises)

Source: Eurostat (trng_cvt_02s)

What are the main skills needed for the development of EU enterprises?

CVTS also asks all enterprises about their overall CVT strategies, and one question concerns the skills that the enterprise generally considers as most important for its development in the next few years, with the possibility to mark the three most important skills. In 2020, EU enterprises considered job-specific skills (43.2 %), team working skills (41.9 %), customer handling skills (36.5 %) as well as problem solving skills (25.2 %) as most important. Looking at the trend, the importance of IT skills is growing, even though they are not among the top skills for enterprise development. At the same time customer handling skills, technical, practical or job-specific skills as well as foreign language skills appear less important in 2020 compared with five years before - see Figure 10.

(% of all enterprises)

Source: Eurostat (trng_cvt_10s)

And what about initial vocational training in enterprises?

The CVTS also collects some information on the provision of initial vocational training (IVT) – see Figure 11. In 2020, almost one third (32.4 %) of all enterprises with 10 or more persons employed in the EU’s business economy provided IVT, although the proportion varied greatly across EU Member States. Only six Member States reported a share that was above the EU average, with around two fifths of all enterprises in Denmark, Italy, the Netherlands and Austria providing IVT, around one half in France, and almost three fifths in Germany. At the other end of the scale, less than 1 in 10 enterprises provided IVT in six of the Member States, namely Hungary, Poland, Greece, Bulgaria, Romania and Lithuania.

(% of all enterprises)

Source: Eurostat (trng_cvt_34s)

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

Sources

The source of data used in this article are data from the five-yearly continuing vocational training survey (CVTS). CVTS collects information on enterprises’ efforts in the continuing vocational training of their workforce. The most recent year for which data are available is 2020. The coverage is enterprises with 10 or more persons employed in NACE Rev. 2 Sections B to N, R and S (therefore excluding agriculture, forestry and fishing, public administration and defence, compulsory social security, education, human health and social work activities).

More information about this source is available in the methodology of the continuing vocational training survey (CVTS).

Key concepts

CVT in enterprises concerns training measures or activities which have as their primary objective the acquisition of new competences or the development and improvement of existing ones. CVT in enterprises must be financed, at least in part, by the enterprise and should concern persons employed by the enterprise (either those with a work contract or those who work directly for the enterprise such as unpaid family workers). Persons employed holding an apprenticeship or training contract should not be taken into consideration for CVT. The training measures or activities must be planned in advance and must be organised or supported with the special goal of learning. CVT can take place on-site, online or both (blended/hybrid learning). Random learning and initial vocational training (IVT) are explicitly excluded.

CVT courses are typically clearly separated from the active workplace (learning takes place in locations specially assigned for learning like a classroom or training centre). They show a high degree of organisation (time, space and content) by a trainer or a training institution. The content is designed for a group of learners (for example a curriculum exists), while two distinct types of courses may be identified – internal and external CVT courses.

Other forms of CVT are typically connected to active work and the active workplace, but they can also include participation (instruction) in conferences, trade fairs and similar events for the purpose of learning. These other forms of CVT are often characterised by a degree of self-organisation (time, space and content) by the individual learner or by a group of learners. The content is often tailored according to the learners’ individual needs in the workplace. The following types of other forms of CVT may be identified:

- planned training through guided on-the-job training;

- planned training through job rotation, exchanges, secondments or study visits;

- planned training through participation (instruction received) in conferences, workshops, trade fairs and lectures;

- planned training through participation in learning or quality circles;

- planned training through self-directed learning/e-learning.

Training enterprises are enterprises that provided CVT courses or other forms of CVT for their persons employed during the reference year.

A participant in CVT courses is a person who has taken part in one or more CVT courses during the reference year. Each person is counted once, irrespective of the number of CVT courses in which they have participated.

The costs of CVT courses cover direct costs, participants’ labour costs and the balance of contributions (net contribution) to and receipts from training funds.

Direct course costs:

- fees and payments for CVT courses;

- travel and subsistence payments related to CVT courses;

- the labour costs of internal trainers for CVT courses (direct and indirect costs);

- the costs for training centres, training rooms and teaching materials.

Participants’ labour costs include the labour costs of participants for CVT courses that take place during paid working time.

The net contribution to training funds is made up of the cost of contributions made by the enterprise to collective funding arrangements through government and intermediary organisations minus receipts from collective funding arrangements, subsidies and financial assistance from government and other sources.

The CVTS also collects some information on initial vocational training (IVT) within enterprises which is defined as a formal education programme or a component of it where the working time of the paid apprentices/trainees alternates between periods of practical training in the workplace and general/theoretical education in an educational institution or training centre. For 2020, the coverage was training within ISCED levels 2–5, in other words, secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education as well as short-cycle tertiary education. The length of IVT should be between six months and six years. Voluntary apprenticeships/traineeships are excluded.

| Tables in this article use the following notation: | |

| : | not available, confidential or unreliable value. |

| – | not applicable. |

Context

Copenhagen process and European initiatives

Since 2002, national authorities and social partners from European countries have taken part in the Copenhagen process which aims to promote and develop vocational education and training (VET) systems. In June 2010, the European Commission presented its proposals for ‘a new impetus for European cooperation in vocational education and training to support the Europe 2020 strategy’. In December 2010, in Bruges (Belgium) the priorities for the Copenhagen process for 2011–2020 were set, establishing a vision for vocational education and training. Cooperation on vocational education and training was further developed by the Bruges communiqué on enhanced European cooperation in vocational education and training for the period 2011–2020 and Council conclusions from a meeting held in Riga in June 2015, whereby those countries participating in the Copenhagen process agreed on a set of deliverables for the period.

In March 2018, the Employment, Social Policy, Health and Consumer Affairs Council (EPSCO) adopted the Recommendation on a European Framework for Quality and Effective Apprenticeships which set out 14 criteria for high quality apprenticeships.

An important milestone of the EU cooperation in VET was the adoption in 2020 of the Council Recommendation on vocational education and training for sustainable competitiveness, social fairness and resilience which also includes three quantitative objectives to be achieved by 2025.

Following up on the adoption of the Council Recommendation VET, in 2020 VET stakeholders signed the Osnabrück Declaration which aims at revitalizing the Copenhagen process by defining concrete actions for the period 2021-2025 at both national and EU level.

To empower all adults to develop their skills throughout their working-age, the Council has adopted a Recommendation on Individual Learning Accounts in 2022. It recommends Member States to consider setting up an individual learning account for all working-age adults and ensure an adequate provision of training entitlements, with additional support for those individuals most in need of up- and reskilling.

To help learners to communicate the skills acquired during personalised learning and career pathways, the Council also adopted a recommendation on a European approach to micro-credentials for lifelong learning and employability. The goal of the Recommendation is that Member States, stakeholders and providers (across education, training and labour market systems) develop and use micro-credentials in a coherent way, boosting mutual trust and recognition.

Jointly, implementation of the Council Recommendations on individual learning accounts and micro-credentials can provide all working-age adults in the EU with the means and incentives to take up training, and is expected to contribute to Member States’ progress towards their national adult learning targets for 2030.

Direct access to

- Participation in education and training (educ_part)

- Continuing vocational training in enterprises (trng_cvt)

- Participation in education and training (educ_part)

Metadata

- Continuing vocational training in enterprises (ESMS metadata file – trng_cvt_esms)

Manuals and other methodological information

- CEDEFOP – European centre for the development of vocational training

- European Commission – Education and training – Adult learning

- European Commission – Education and training – Vocational education and training

- OECD – OECD policy reviews of vocational education and training (VET) and adult learning

- UNESCO – Institute for lifelong learning

- UNESCO – Strategy for technical and vocational education and training (TVET) (2016-2021)