Physical imports and exports

Data extracted in July 2023

Planned article update: 31 July 2024

Highlights

In 2022, physical imports into the EU were around 3.6 tonnes per capita, while physical exports were around 1.5 tonnes per capita.

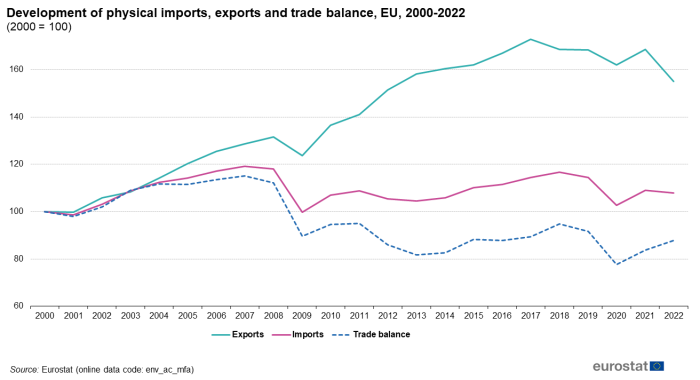

Development of physical imports, exports and trade balance, EU, 2000-2022

While the European Union's (EU) trade balance in monetary value is more or less even, its physical trade balance is clearly asymmetric. The EU imports more than two times more goods by weight from the rest of the world than it exports. Quantitatively the physical imports into the EU are dominated by fossil fuels and other raw products which typically have low value per kilogram. On the other hand, the EU exports high-value goods such as machinery and transport equipment. Data on physical imports and exports are collected in the framework of material flow accounts which are presented in more detail in the article material flow accounts and resource productivity. Related articles discuss resource productivity statistics and material footprints.

Full article

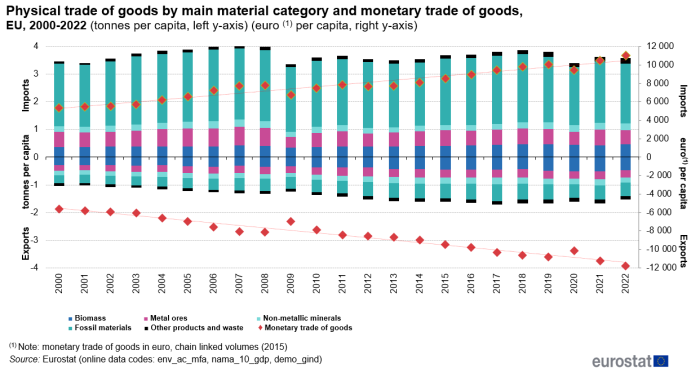

In monetary terms, the EU's trade in goods is balanced; imports and exports are more or less in the same order of magnitude and both have almost doubled since the year 2000 due to globalisation. From a physical perspective however — measured as the actual weight of traded goods — the EU's trade pattern with the rest of the world is quite different (see Figure 1). Physical imports are around 3.6 tonnes per capita while physical exports are around 1.5 tonnes per capita.

Source: Eurostat (env_ac_mfa) (nama_10_gdp) (demo_gind)

Up until the start of the financial crisis in 2007-2008, both physical imports and exports increased, more or less, in parallel (see Figure 2). Since then, however, physical exports by and large continued their growth path while physical imports dropped and stagnated for some years. Physical imports' development is mainly determined by fossil materials. The COVID-19 recession caused a fall in both physical imports and exports, whereby the former was more pronounced than the latter because of a lower demand for imported fossil energy materials.

Source: Eurostat (env_ac_mfa)

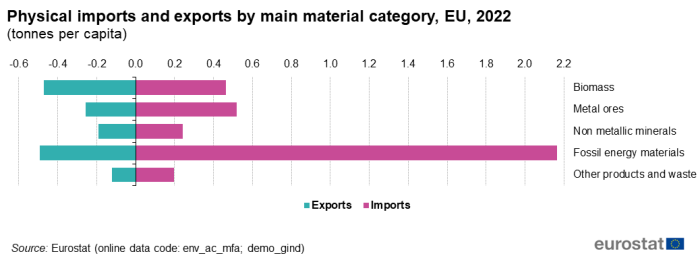

A closer look at the traded goods in a breakdown by four main material categories (original data are available in a more detailed breakdown by around 50 material categories) reveals a clear asymmetry between physical imports and exports (see Figure 3). Imports of fossil energy materials are most significant with more than 2 tonnes per capita — for this material category physical imports are about four times bigger than exports. Imports assigned to the category of metal ores amount to around 0.5 tonnes per capita and are almost twice more than the exports. Physical trade is more balanced for the other categories, namely biomass (around 0.5 tonnes per capita) and non-metallic minerals (around 0.2 tonnes per capita).

Source: Eurostat (env_ac_mfa) (demo_gind)

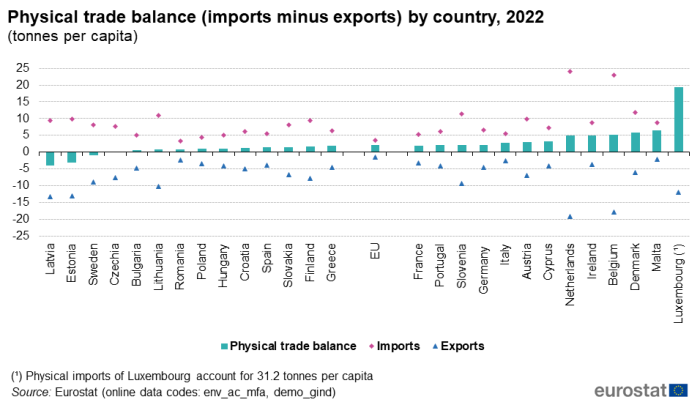

Figure 4 shows the physical trade balance (weight of imported goods minus exported goods) for all EU Member States. In physical terms, most EU Member States import more than they export (i.e. net importers). There are only a few net exporting countries, namely Estonia (wood, fossil energy materials) and Latvia (wood).

Source: Eurostat (env_ac_mfa) (demo_gind)

Physical trade by stage of manufacturing

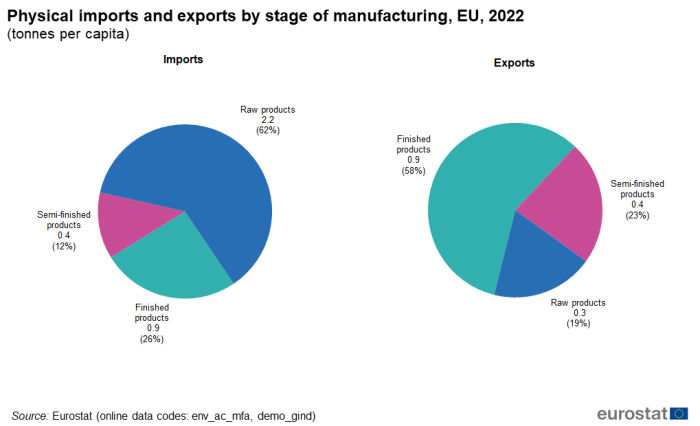

Eurostat also provides data on physical imports and exports of goods in a breakdown by stage of manufacturing (see Figure 5). A distinction is made between three stages: finished products, semi-finished products and raw products.

The EU's physical exports are dominated by finished products whereas the physical imports are dominated by raw products. The EU economy is specialised in the transformation of low-value raw products into high-value finished and semi-finished products.

More than 62 % of the EU's total physical imports are raw products. On the other hand, around 58 % of the EU's total physical exports are finished products.

Source: calculation based on Eurostat (env_ac_mfa) (demo_gind)

Import dependency

As shown above, the EU economy depends on raw materials from the rest of the world. This can be further analysed using economy-wide material flow accounts (EW-MFA). Import dependency, a metric derivable from EW-MFA, denotes the share of physical imports in the direct material input (DMI) of a given economy (the DMI comprises domestic extraction and physical imports).

The import dependency can be broken down by main material categories. Table 1 shows that the EU economy is almost self-sufficient in the supply of non-metallic minerals (construction materials) and biomass with import dependencies just over 3 % and more than 12 %, respectively. For metal ores as well as for fossil energy materials, the EU is highly dependent on imports from the rest of the world (more than 50 % and around 70 %, respectively).

Raw material equivalents — towards a global perspective

Physical imports and exports are measured in mass weight of goods crossing the border, regardless of how much the traded goods have been processed. The total weight of raw material extractions needed to produce manufactured goods is usually several times greater than the weight of the goods themselves.

Physical imports and exports can be complemented with supplementary estimates of the amounts of raw materials needed to produce traded goods. This can be done by converting the traded goods into their raw material equivalents (RME), i.e. the amount of raw materials that need to be extracted to produce the traded goods in question. More details on imports and exports in RME can be found in the article Material flow accounts statistics - material footprints.

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

This article uses data from economy-wide material flow accounts (EW-MFA), which are one of the European environmental economic accounts (see Regulation (EU) No 691/2011 on European environmental economic accounts).

Economy-wide material flow accounts (EW-MFA) provide an aggregate overview, in thousand tonnes per year, of the material flows into and out of an economy. EW-MFA cover solid, gaseous, and liquid materials, except for bulk flows of water and air. Material inputs into national economies include domestic extraction of material originating from the domestic environment and physical imports originating from other economies. Material outputs from national economies include materials released to the domestic environment (e.g. emissions to air, water and soil) and physical exports to other economies. Material flows within the economy are not represented in EW-MFA.

A variety of material flow-based indicators are derived from EW-MFA amongst which the following:

Domestic material consumption (DMC) measures the total amount, in tonnes, of material directly used in an economy, i.e. by resident businesses, governments and other institutions for economic production or by households. DMC equals the domestic extractions of materials plus imports minus exports. At the same time, DMC is the amount of materials that become part of the material stock within the economy or are released back into the environment, for example, in the form of air emissions.

Resource productivity is defined here as GDP divided by DMC. It is important to note that GDP is expressed in different measurement units, of which the following are used to calculate three different resource productivity ratios. The appropriate choice depends on the context of the analysis:

- euro per kilogram using chain-linked volume data for GDP, to be used for analysing developments in real terms over time;

- PPS per kilogram using current price data for GDP expressed in purchasing power standards (PPS); PPS are artificial currency units that remove differences in purchasing power between economies by taking account of price level differences; these can be used when comparing across different economies at one point in time (for one particular year);

- euro per kilogram using current price data for GDP, which could be used when analysing a single economy at one point in time (for one particular year).

See also MFA metadata.

Decoupling

The term decoupling refers to breaking the link between an environmental and an economic variable. As defined by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), decoupling occurs when the growth rate of an environmental pressure (for example, DMC) is less than that of its economic driving force (for example, GDP) over a given period. Decoupling can be either absolute or relative. Absolute decoupling is said to occur when the environmental variable is stable or decreases while the economic driving force grows. Decoupling is said to be relative when the rate of change of the environmental variable is less than the rate of change of the economic variable.

Context

Eurostat's environmental accounts and statistics inform policy making under the European Green Deal. The European Green Deal is the first of six priorities of the European Commission for the period 2019-2024. It is a growth strategy that will transform the EU into a modern, resource-efficient and competitive economy, where there are no net emissions of greenhouse gases by 2050, economic growth is decoupled from resource use, and no person and no place is left behind. The European Green Deal boosts the efficient use of resources by moving to a clean, circular economy, restore biodiversity and cut pollution. The European Green Deal is the plan to make the EU's economy sustainable.

Further reading:

A European Green Deal – EC website

Communication and roadmap on the European Green Deal

Publication: A new Circular Economy Action Plan for a Cleaner and More Competitive Europe

Communication: A new Circular Economy Action Plan for a Cleaner and More Competitive Europe

Direct access to

- Environment (env)

- Material flows and resource productivity (env_mrp), see:

- Material flow accounts (env_ac_mfa)

- Resource productivity (env_ac_rp)

- Circular economy, see:

- Circular economy indicators (cei)

Publications and EU policies' monitoring frameworks

- European Commission — Environment — Circular economy

- European Environment Agency: The European environment — state and outlook 2015 SOER 2015

- European Environment Agency: The European environment — state and outlook 2020: knowledge for transition to a sustainable Europe SOER 2020

- OECD — Resource efficiency