Archive:Services producer price index - filling a gap in macroeconomic statistics

This Statistics Explained article has been archived - for recent articles on short-term business statistics see here.

- Published in Sigma - The Bulletin of European Statistics, 2007/02

The evolution in short-term statistics has followed that of European Union (EU) policies. For the first 40 years, most Community policies were structural and EU statistics were only published annually or sometimes even less frequently. Back then, Eurostat collected whatever data were produced by the NSIs and simply put it together.

This changed in the mid-1990s when it became clear that the EU was heading towards economic and monetary union and that short-term statistics (STS) were needed in order to manage monetary policy.

Introduction

‘We realised in the EU community that a more solid basis for short-term statistics was needed’, says Brian Newson, Head of the Short-term Statistics Unit D3. ‘Until then, STS mainly focused on manufacturing. The first STS regulation was adopted in 1998, introducing the requirement to provide services turnover at current prices on a quarterly basis.’

By the early 2000s, both Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs in Brussels and the European Central Bank were focusing on short-term developments in the newly created single economy of the euro area. It was clear that better data were needed. In addition, the ever-increasing importance of services in our economy could not continue unmeasured.

Eurostat started to work in 2002 towards amending the STS regulation, to accelerate the transmission of data in the first place and to include output prices for services, which were missing from the 1998 regulation.

New STS regulation

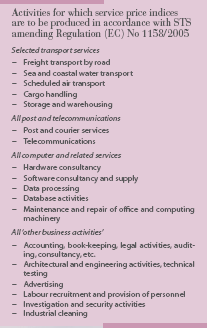

The regulation was amended in July 2005 and required Member States to provide a services producer price index (SPPI), broken down by type of service, on a quarterly basis, from 2006 onwards (see box on page 37).

As regards implementation of the SPPI at national level, the picture varied greatly from country to country. With the exception of some Member States doing theoretical work on the subject, such as Finland, France, Sweden and the UK, in general most Member States were not involved in the collection of service prices until 2005. The amended regulation obliges Member States to collect service prices but allows them transition periods, mostly to August 2008, but sometimes longer, for some activities or smaller Member States.

‘At present, only half a dozen Member States are providing output prices for some types of service. If all goes as planned, we will be able to produce the first EU SPPI aggregate by the end of 2008. That is, if we have enough coverage in terms of turnover for the euro area and the EU levels’, says Isabelle Rémond-Tiedrez, a member of Eurostat’s Short-term Statistics Unit.

Benefits of a services price index

‘The SPPI is useful in its own right as a measurement of inflation and to analyze the origins of inflation, as services account for over half of modern economies. Inflation experienced by consumers is measured by the harmonised index of consumer prices. But for economists it is also important to know which industries are the sources of price increases, now only known for goods and not for services’, says Mr Newson.

‘A weakness of the present STS is that services turnover is at current prices, so it is difficult to tell which change in value is due to growth, or change in volume, and which is due to a change in price. Once we have complete service prices, the SPPI will act as a deflator by applying it to services turnover (the volume) and enabling a comparison to be made over a given period’, says Ms Rémond-Tiedrez.

‘In addition, services are a significant component of gross domestic product. So better statistics on service prices and volumes will help provide more reliable estimates of GDP growth’, continues Mr Newson.

Those who will benefit most from this index are players in the macroeconomic policy field: the European Central Bank, Commission directorates-general such as Economic and Financial Affairs, Transport, Enterprise and Internal Market and Services, national governments and financial markets.

Challenges in collecting service prices

Services are rather heterogeneous. The notion of price is the value per unit. The problem is to identify the unit of a service. Let’s take, for example, legal activities. Are fees per hour the correct unit? This may vary depending on the size of the client or project. In addition, services often come bundled in a package, as happens in IT-related services, making it difficult to disentangle the price of the service from the product. Another particularity is that, unlike goods, a service cannot be resold, which allows service providers to charge quite different prices to different customers. Thus, the creation of a set of SPPIs is complex and costly — even more so when they are to be compared at European level. As in all price statistics, quality adjustment is a crucial issue, especially given the reasons just mentioned.

Working together for maximum comparability

While the long derogation period is inconvenient for users, Eurostat is using it positively to work with the NSIs to jointly develop methods and indicators. This will ensure maximum comparability from the start for the indices when ready. The sharing of best practices will also help keep costs and burden as low as possible. The first step was the publication in February 2006 of a manual together with the OECD: a Methodological guide for developing producer price indices for services. Eurostat then organised a workshop in October 2006 to share experiences in the compilation of SPPIs and to disseminate the practices presented in the SPPI guide. Some 30 countries participated, including both EU and non-EU countries such as the USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Japan, together with the OECD, as the services price index has international relevance.

Scope of the index

The idea was to measure the output prices of services offered to all, whether to consumers or enterprises. However, as consumer consumption is measured by the consumer price index, the regulation stipulates that as a minimum requirement only business consumption (business-to-business) need be covered, to avoid the duplication of efforts.

All market services sold at some kind of market price should be covered. Public services are excluded, as the notion of price is not obvious and the ways they are provided are very different from country to country, as for example with health and education.

Going forward

‘Our objective is to implement the 2005 regulation successfully and arrive at the beginning of 2009 with this new index, SPPI. In the medium term, this would allow us to have a volume index of services output, such as the volume index of industrial production, which has existed for over 50 years. That would give us a better picture of growth in services, and in turn, a better picture of GDP growth’, ends Mr Newson.